John Bunker: ‘Hot Ironies: Another Perspective on Beatriz Milhazes’

Beatriz Milhazes, Detail from ‘Marilola’ (2010-15), aluminium, brass, acrylic, enamel, polyester and paper flowers, resin, foiled paper, wood and hand painted enamel on aluminium, 290 x 280 x 44cm

The work of Beatriz Milhazes eludes classification. To align her too closely with a certain strain of modernist abstraction, or with the postmodernism that rehashes its tropes, is to miss far more interesting and complex visual and historical connections. There are other things to consider, besides, say, comparisons between her paint application and that of Hans Hofmann: there is the degree to which she has been influenced by the painterly possibilities of faded tiling on Brazilian Baroque churches, or the peeling paint on the rotting porticos and colonnades in the old colonial buildings of Rio de Janeiro. There is, to give a further example, also the matter of her long-held fascination with the modernist landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, whose re-imaginings of the idea of truly public spaces and parks speak of an egalitarian modernist sensibility that seeks to reconnect man with nature: rather than importing colonial horticulture from more temperate climes, he put Brazil’s rampant and beautiful tropical vegetation centre stage. All of this is present in Milhazes’ paintings, collages, and three-dimensional works.

Milhazes helps herself to whatever she requires from the modernist canon: Matisse’s Moroccan period of 1912-13, during which his use of repeated decorative motifs inspired by Islamic textiles allowed him to explore colour on its own terms, testing its spatial and emotive possibilities, is an unmistakable point of reference for the works hanging at White Cube; as are later modernist explorations of colour found in Systems and Op art, that particularised the power of colour released through pattern and dynamic contrasts ; but Milhazes plays with how these modernist innovations are mediated by other kinds of cultural experience and historical contexts. In doing so, she deploys a kind of irony: not the cold kind, born of the nihilism of the postmodernist sensibility, but a ‘hot’ irony, implicit in the emotional charge of her elaborate collagic procedures. Its heat can be felt throughout the history of modernism, wherever the supposed high and low forms of cultural production have clashed; and it is felt with a particular intensity where visual cultures from non-Western centres collide and meld with notions of abstraction which are viewed as originating in Western modernity. Where exactly does it come from, this ‘hot’, and, I would argue, creative irony?

Maybe it finds its origin in the contradictory purposes at the roots of modernity. The European mission to modernise has been proven to be a complex and contested process: clearing away the old, superstitious, primitive world for a clean, logical and productive one has, time and again, turned out to be a deeply flawed enterprise. Grand ideas about progress have always been tainted by political and economic expediency, and have had complex, unpredictable consequences for the societies in which they have been put into practice. It is necessary to recognize that in a global context, aspects of this project are linked to empire and the extension of colonial rule just as much as they are to linked to reform and revolution. Beneath the camouflage of ‘progressive’ thought hides Europe’s drive towards absolute power, through expansionism, the acquisition of natural resources, and the enslavement or destruction of subject populations; this is the shadow self of the Enlightenment, and glimpses of it can be seen in the paternalistic fantasies of the ‘other’, the primitive and the primordial, projected onto non-European peoples by their oppressors, that have guided so much of the trajectory of modernist art. Milhazes’ ‘hot’ irony can be understood as her chosen mode of working both with and against the legacy that modernism has foisted on post-colonial Brazil: she is simultaneously both critical and celebratory. The irony lies in the way in which she repurposes the visual tropes of European modernism to evoke a particularly Brazilian brand of cosmopolitanism; and the heat comes from the friction created as these tropes jostle together in her crowded, layered, polychromatic images.

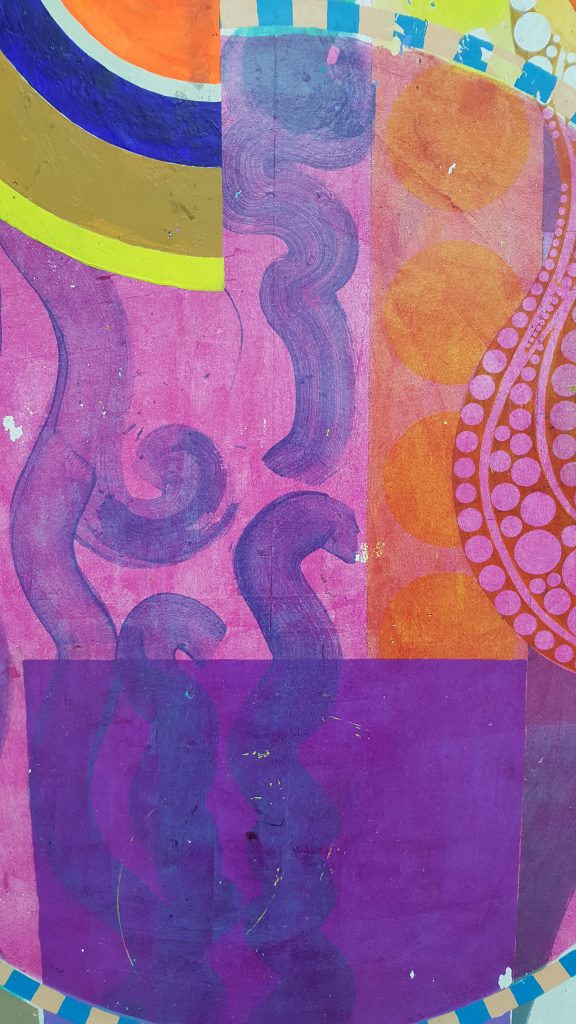

Beatriz Milhazes, Detail from ‘Coqueriral em Marron e Azul Celeste’ (2016-17), acrylic on canvas, 279 x 189.5cm

The paintings’ eviscerated surfaces are worked up in an elaborate play between additions and subtractions of transferred painted imagery. Frankenstein-like transplantations of ripe and flowering horticultural imagery are layered over architectural forms and painterly devices derived from modernist iconography. The distressed surfaces might seem overworked and over-engineered: but on the other hand, had she chosen ‘wet into wet’ spontaneity, that too has its limitations; and her careful layering of imagery has its own peculiar painterly intensities. Milhazes considers the history of the mark-making process, the natural incompleteness, and the accidental slippages and breakages of the transfer process as absolutely integral to the final painterly image. Despite the apparent exuberance of her work, the allegorical connotations that attach themselves to a painting process heavy with broken surfaces seem to suggest that her use of bright colour and dense physicality has, in fact, a melancholic undertow: one is reminded of the processes of decay, as burgeoning nature slowly but relentlessly grows into the weathered cracks of seemingly endless modernist concrete facades. This kind of irony casts a strange, revealing light on the nature of progress and tradition: what were once seen as emblems of cutting-edge modernity are now recast as symbols in a kind of painterly drama of entropic decline. Milhazes brings back Sonya Delaunay’s dynamic discs from the turn of the 20th century, and Bridget Riley’s cool, crisp, optimistic rhythms from the 1960s; but in her re-imaginings, these tropes begin to buckle and fragment under the weight of their own histories- freighted as they are with the unrealised hopes for a more egalitarian world, and with the longing for a new kind of visual culture that might just as easily be born of modern city street lights, shop fronts, modern architecture and design, rather than the grand Western Tradition.

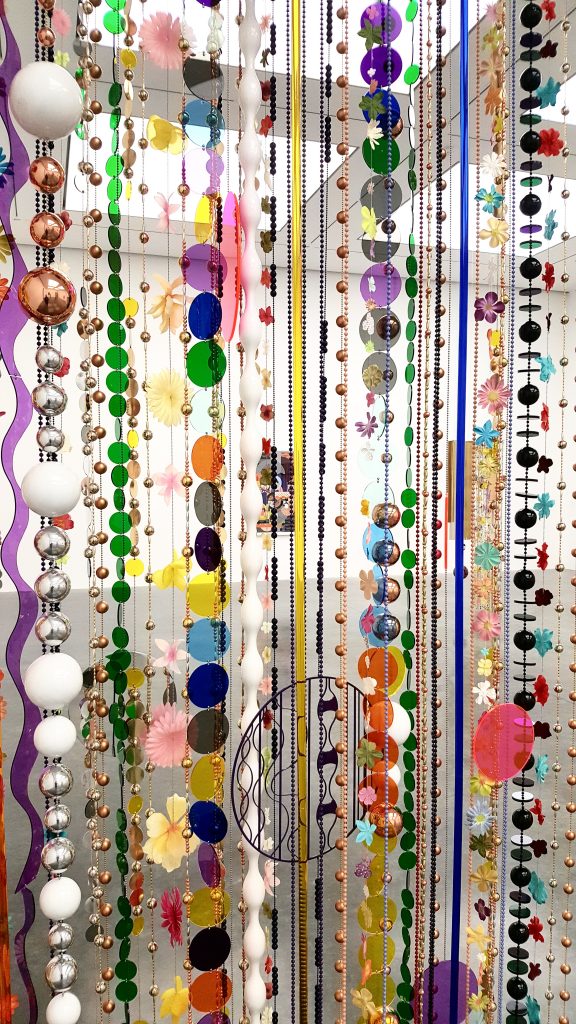

Beatriz Milhazes, Detail from ‘Marilola’ (2010-15), aluminium, brass, acrylic, enamel, polyester and paper flowers, resin, foiled paper, wood and hand painted enamel on aluminium, 290 x 280 x 44cm

The paintings in the show work in one way: the collages and three-dimensional pieces, in another. The elaborate cascades of beads, baubles, imitation flowers and jewel-like fragments that pour down in the chandelier-like forms that hang in the 9x9x9 space suggest a joyous celebration of kitsch; but it’s kitsch mediated by highly sophisticated colourplay and sheer complexity in the elaboration of forms, and in their highly polished finish. Again, though, is all what it seems? These high production values are echoed in the first part of the South gallery by the high-end shopping references that call out from the stunning series of collages, each exquisitely crafted from the packaging of international brand named stores, each with its own unique colour signature formed from its luxurious printed materials; but in constructions and collages alike, there is a sort of sophisticated delirium at work. The collages, in particular, operate like feverish machines, maniacally reconfiguring what seems like a plethora of visual possibility, mediated by the psychologically charged colour regimes of consumer culture; but to what purpose? are they affirming, or questioning? Much has been made of Milhazes’ interest in carnival culture: but the evocation of it in her work proves to be as problematic, and as double-edged, as carnival itself has become. Carnival might once have been the anarchic, spontaneous celebration of the burgeoning energy and creativity that defied the harsh realities of city living, caught between a repressive regime and grinding poverty; but it is now widely seen as having turned into a series of highly sophisticated choreographed ‘spectacles’ staged for the tourist’s gaze. True carnival is a polyphony of competing voices, a raucous recognition of the contradictory nature of being human, in which all manner of political, religious and sexual identities are held up for scrutiny in a special kind of performative flux, a polymorphous plurality; and in all this, a cacophony of humanly-felt ironies abound. But all is silent here in the White Cube…. the earthy density, the physicality and weight of the paintings- which can be read as metaphor for the earthiness of true carnival- are conspicuously absent from the complex arrays of brightly painted objects and suspended translucent coloured shards of ornamental perspex, plastics and glass that never quite form cogent sculptural wholes. They act like elaborate curtains or veils that one might constantly peer through rather than at or into; and in their insubstantiality, they evoke the hollowed-out kitsch of the carnival show.

Beatriz Milhazes, Detail from ‘Hawai em Indra pretax e Brancas’ (2015-18), collage on paper, 120 x 133cm

Artists who were perceived as outsiders to the western art world are now finding their place within it; and in this respect, Milhazes is a trailblazer. They use aspects of modernism’s history of forms as tools with which to dismantle it; and in doing so, I would argue, they have greatly enriched our understanding of it. And they go further: through this process, they are able to allude to the often brutal paradoxes at work in the wider culture, where the shrinking of the world to a ‘global village’, giving us access to what had been until recently fugitive or hidden visual cultures, all brought to us in high definition, up close, in slow-mo, all made possible through ever more efficient production and dissemination of images, has its dark counterpart in the movement of organized trafficking of the displaced and the dispossessed, uprooted at the whims of the new empires built on international corporate power. Again and again, Milhazes, through interfering with the signals of pure sensual enjoyment that her work seems designed to send, invites a questioning, ironical reading that extends beyond the image, and into the global culture industry of which it forms a part. And there can be no doubt that someone with her keen eye for irony, and whose work deals so subtly with the the machinations and manifold contradictions in the way we perceive contemporary abstract art, will have thought long and hard about showing it at White Cube, which functions, in effect, as an almost archetypal neoliberal cultural power broker.

Born in the fusion, as the artist herself eloquently puts it, ‘of symbol and matter’, Milhazes’ works create a slow but insistent paradoxical burn. They seem to be goading us to let go of the idea that abstraction can provide some notion of a purely visual, unmediated transmission of universal spiritual values: the moment we abandon these untenable mythologies about the experience of looking at abstract art, they seem to suggest, the sooner we will start to enjoy it in the real sense; that is, the complex, historically and socially mediated sense. For all their decorative exuberance and tropical iconography, they smoulder with an ironical, critical heat: a heat fuelled by the contradictory narratives at the heart of the history of abstraction, that continues to sting the mind’s eye long after one has left the gallery.

Installation view of Beatriz Milhazes, ‘Rio Azul’, 2018

6 thoughts on “John Bunker: ‘Hot Ironies: Another Perspective on Beatriz Milhazes’”

Comments are closed.

Loving the writing, John.

“…a ‘hot’ irony, implicit in the emotional charge of her elaborate collagic procedures”.

Really? But I came out of the show unmoved by anything – any specific thing, that is – and I consider myself quite sensitive to both expressivity and irony. If you look at the hangings with any degree of interrogation, they will repay you not with “complexity in the elaboration of forms”, but only with the utter banality of their structures, the obviousness in the presentation of appropriated materials to which very little has been done, and the passivity of the gaudy exoticism which is being passed off as transgressive expression. Not so. These works are dumb, in the profound sense of wishing for an art that “speaks” to you in some way through its visual convictions, the persuasiveness of which might take you somewhere beyond the obvious structural clichés seen here.

Once you “get” the dumbness of the hangings, you then start to see that same lack of engagement in the collages, and even eventually in the paintings – which might well be the best of the work, but which display a certain archness and cuteness in their phony decaying surfaces. Not once did I find two things conjoining in a way that could be described as “felt”, which is another way of saying that the parts have no genuine visual bearing upon one another – and the details shown here confirm that stark lack of touch. And no, I’m not arguing for wet-on-wet Hofmannesques or any such thing, merely for a sensitivity to decision-making that is lacking. Nor, categorically, am I arguing for “the idea that abstraction can provide some notion of a purely visual, unmediated transmission of universal spiritual values”. No thank you. I just want something compellingly good to look at, and so long as it has that, it can bring along all the baggage it wants. But baggage alone does not make art.

Nor, for goodness sake, do they smoulder! I rather feel that her Latin-American voice, if she has one, is compromised and muted by the imported tropes of western modernist abstraction. The anarchic (and profoundly figurative) spirit of carnival hardly makes itself felt here in work that seems to me to reside quite happily and uncomplainingly in the neoliberal-cultural-power-broker model of White Cube, where the overproduction of bloated semi-muted-aesthetic gigantisms, in the service of ubiquity and depersonalisation, is the name of the game. The high-end shopping experience of the collages confirms a cynical approach to the prospect of high-end sales. I think, in short, this work is pretty rubbish. Very, very sub-Sonia Delaunay.

By the way, the detail from ‘Hawai em Indra pretax e Brancas’ is a dead-ringer for how a John Bunker collage from five years ago was organised. Just saying.

I’m also struggling to see the irony of Milhazes showing at White Cube. Such a pairing seems to very much reflect the neoliberal model that galleries like White Cube represent. They appear to champion artists from “marginalised communities”, despite the fact the individual artists are rarely if ever themselves marginalised. This gives the institution a smug veneer of appearing keyed into minorities and grass roots movements, and this filters through into liberal audiences who feel they have taken a step outside of their comfort zone, whilst not having left the insulated safety of the Western museum.

The traffic seems all one way to me. Rather than introducing a Western audience to a uniquely Brazilian perspective, White Cube have presented work that seems to be thoroughly colonised. I wouldn’t necessarily reproach any artist for accepting these sorts of opportunities. They are rare, but less so for artists like Milhazes.

We also have to remain wary of the tendency for powerful institutions to take in minority voices as a way of silencing them. The dissident gets consumed and drowned out, and has to assimilate, but elects to remain ‘inside’ out of the deluded view that s/he can achieve more from within. It happens in politics all the time. I think it happens in contemporary art as well. But in the case of Milhazes, I think it’s a bit different. I cannot identify anything politically subversive in her work, which is probably why it is permitted to prosper in the public light. It’s completely inoffensive.

Ethnic Irish transgressive art

http://www.bennysweeney.com/

Some seek the sublime in Art, some in the mountains.

I came across in Robert Macfarlanes introduction to the Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd a mountaineering metaphor. Macfarlane says that Nan Shepherd came to know the Cairngorms ‘deeply rather than widely’. What he means is that she immersed herself completely in a particular landscape to the exclusion of other habitats, and that specific landscape, the Cairngorms was the subject of all her writing.

Macfarlane says that most writing about mountains is by men. and that these focus on the summit, success being when the mountain is conquered.

‘But to aim for the highest point is not the only way to climb a mountain, nor is a narrative of siege and assault the only way to write about one’.

When younger, Shepherd ‘made always for the summit’ but later ‘circumambulation has replaced summit-fever; plateau has substituted for peak’. She ceased to have interest in the peak ‘from which she might become catascopos the looker-down who sees all with a god-like eye’.

I was struck by this similarity to much critical writing on art. The certainty and singularity of this ‘god-like eye’ in art criticism often seeks the diminution and obliteration of other perspectives and experiences. How much richer to experience the whole; in this analogy, the plateau, from which different summits arise? High Modernist criticism is often intolerant of difference and particularly in the area of abstract painting where philosophical contortions of great complexity can be concocted to confuse, bewilder and obfuscate, to frequently demean alternative views.

Instantloveland is refreshingly different; there are a couple of posts that I have particularly enjoyed for their openness, generosity and deep knowledge of modern art practices and its times and contexts.

The first of these, Ideologies: Divisions, Schisms, Isms and Unbelievable Gulfs by EC, challenges these insular self-obsessed self-satisfied certainties, that ‘flashy showing off of intellectual prowess by pundits determined to learn nothing from one another . . . . fundamentally a lack of generosity.’

For generosity read John Bunkers review of Beatriz Milhazes at White Cube although it has already attracted a thread that is ‘old school’!

JB refers to ‘untenable mythologies’ and suggests that Milhazes challenges us, as she has been, ‘to look at the contradictory narratives at the heart of the history of abstraction’.

I’m not interested in wasting time reading art criticism whose sole intent is to demean others in the guise of exploring high cultural aim. Such writing diminishes those authors. They have more in common with Love Island or Made in Chelsea than they realise.

Last word, from Nan Shepherd.

‘Plateau is the true summit of these mountains; they must be seen as a single mountain, and the individual tops . . . no more than eddies on the plateau surface.’

Instantloveland. A breath of fresh art critical air.

Great, I love irony.

I have no patience for art writing, it is rarely art, rarely illuminating; seems written only for other art writers. Hard to read the above, too much in the head. I loved Milhazes’ early work for its glimpse into the astral world, and the recent work seems to be a victim of its own early success; studio assistants, commercial demand, fame, bogging down the spiritual insight …