‘A Fly on the Ceiling’: Matt Dennis in conversation with David Evison

Embedded in every belief system are the stories of that system’s origins; what the sceptically-minded might prefer to call its Creation Myths. In the case of the secular faith known as High Modernism, the tale of how a particular strain of abstract sculpture came to pre-eminence in Britain in the 1960s has been told and re-told countless times, to the point where pretty much everyone with any sort of interest in advanced art of the post-war period must have at least an inkling that it all reputedly began with Anthony Caro’s first meeting with Clement Greenberg in the USA at the end of the previous decade, and snowballed from there.

It was as a direct result of Greenberg’s prompting that Caro renounced the figurative carving and modelling that up to that point had been his stock-in-trade in favour of a radically reductive, radically abstract language of welded steel components, and lo, a revolution in sculpture was born. Over the next several years, the sculpture school at St Martin’s (where Caro, prior to his conversion, had already been on the staff under Frank Martin) became both think tank and proving ground for this revolution; the testing and taking apart of sculpture’s conventions often moving at such a pace and pitch that Caro found himself overseeing developments in the sculpture studios that he hadn’t yet caught up with in his own practice. And in 1963, the year in which ‘the sixties’ proper, with all their attendant possibilities, actually seemed to finally begin, Caro’s welded sculpture was shown at the Whitechapel Gallery, followed in two successive years by groups of the ‘New Generation’ sculptors, all of whom had studied under him.1 Alongside them, there were also Michael Sandle, who had been at the Slade, and Derek Woodham and Roland Piche, both of whom trained at the RCA).

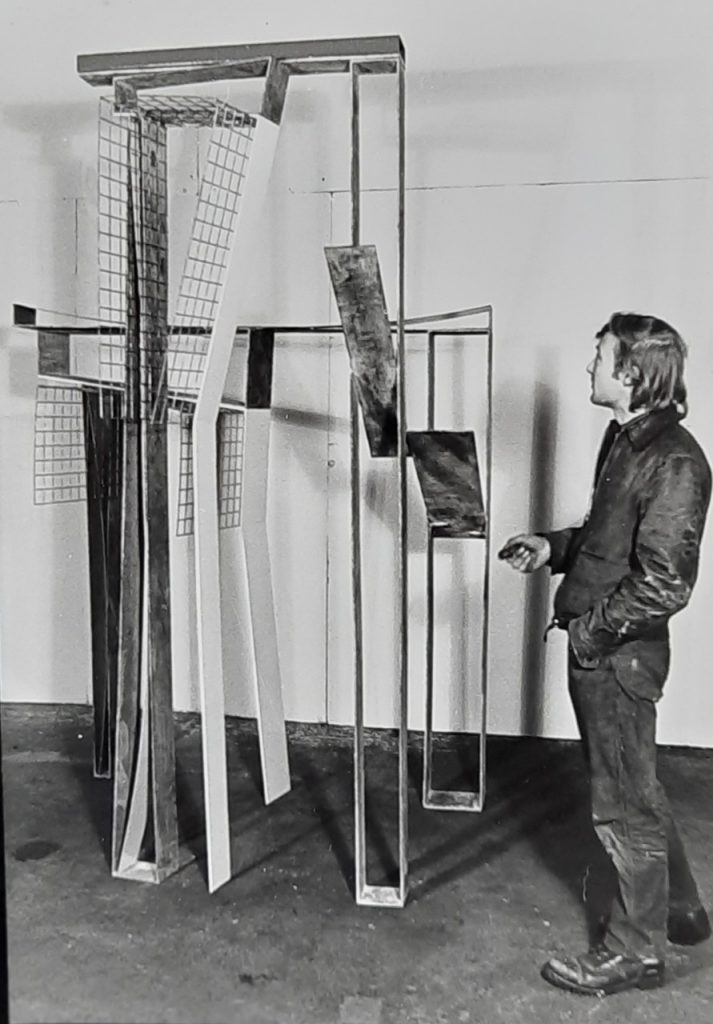

David Evison (b.1944 in Guangzhou, China) was first a student on Harry Thubron and Alan Green’s Basic Course at Leeds College of Art, one of the most progressive art schools in England during the 1960s. Only turning to sculpture- he insists- as a result of happening upon a free and plentiful supply of Perspex, he moved on to Postgraduate study on the Sculpture Course at St Martins, before joining other sculptors from the course in establishing the artists’ cooperative studios at Stockwell Depot. He returned to St Martins to take up a teaching position in the early 1970s; he has subsequently travelled and worked extensively in Western Europe, the USA, China, Japan and South Korea. A great deal of his teaching career has taken place in Germany, where he currently holds the post of Ruhestand-Emeritus Professor at the Universität der Künste, Berlin. He lives and works both in Berlin and in St Leonards on Sea.

Having first studied, then practiced, and then taught during the years of upheaval that began with the ushering-in of the ‘New Sculpture’, David Evison is well-qualified to offer eyewitness testimony on the era’s events. Responding to questions posed via email, he fleshes out the bare outlines in vivid fashion, not holding back when it comes to recollections of certain key personalities who, in their time, weren’t particularly inclined to hold back either: most notably Greenberg, whom Caro first encountered not, as the official history has it, during the latter’s first American trip, but during the former’s visit to London, when Greenberg toured artists’ studios with William Turnbull as his guide. Greenberg’s reaction to viewing his figurative work- as Caro explained to Evison- wasn’t, as is widely believed, to offer the famous piece of advice, ‘If you want to change your work, change your habits’, but rather, to ask: ‘What’s a talented artist like you making crap like this for?’

MD: You started on the Advanced Sculpture Course at St Martins in 1967, by which time Caro’s revolution had been under way for the best part of the decade. What expectations did you have of the course, practically and theoretically? Were these expectations met?

DE: I attended St Martins for just one year, owing to the dire financial straits I was in. The course was unofficial, but I still managed to obtain a grant from the London County Council. I wanted to be there, because sculpture teaching at St Martins was widely thought of as aggressive and superior, due in large part to the success enjoyed by the sculptors on the staff, and this attitude caught on with the students; as far as we were concerned, the RCA, the Slade and Central were the pits. Both Caro and Frank Martin, the Head of Sculpture school, were ex-Royal Navy; and Martin was proud of his ‘men’, making sure that photos of their work were prominently displayed in his quite public office. There was an almost militaristic feel to the organisation of the place, ambitious and determined to win.

Most of the intake were foreign students, who, like me, were attracted by the fact that several of the ‘New Generation’ sculptors2Apart from Caro, there was Philip King, Tim Scott, David Annesley, Michael Bolus and Isaac Witkinwere teaching part-time there. There were two studios for the Advanced Course: one on the 5th floor, one in the basement where all the welding took place. We were a group of between twelve to fifteen students, crammed into a very light and high space. There was no information about the course, and no curriculum; facilities and workshops were very basic, verging on the primitive, and soon the foreign students started to grumble about it being a rip-off. It was.

Phillip King- whose work at that time was better known than Caro’s- seemed to be in charge, and he told us on the first day of the course that he would be coming back in four weeks’ time to see our work. I decided to avoid all the jockeying for workspace by hanging a sculpture from a big hook and working downwards. King returned as promised, getting angry when he saw that we hadn’t done much, and stalked out, not returning for another three weeks.

King initiated discussions about modern sculpture, illustrated with slides. No-one seemed able to understand Rodin; the general opinion was of a 19th-century Richard Wagner type, an assessment intended as a put-down. Brancusi fared better: he was probably the most revered sculptor amongst the St Martins clique. William Tucker came to the session on Brancusi’s work, adding first-hand knowledge gleaned from adventures in Romania and Târgu Jiu.3https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sculptural_Ensemble_of_Constantin_Br%C3%A2ncu%C8%99i_at_T%C3%A2rgu_Jiu.

I put my foot right in it by telling the assembled throng that I loved Bernini, which was greeted by howls. It was good-natured and none too theoretical or ‘artspeaksy’; the bullying and intimidation had not yet begun.

I made friends with Alan Barclay, Luise Kimme and Irmine Kamp. The Germans eventually became Professors at Düsseldorf Akademie, Irmine going on to become Rektor. Alan, a Canadian from Toronto, became Head of Sculpture at Berkley, CA. It was from fellow students that I gained the most.

MD: Was there still a sense of Greenbergian orthodoxy being the ‘house style’ as regards how sculptural theory was taught?

DE: Everything changed in the spring of my year there, when Caro breezed in. Hampstead-posh, wearing tie and tweeds, a real show-off. He knew how to get all us youngsters on his side. He was impressive in his grasp of contemporary art, and in the degree of his motivation in making it. He never mentioned Clement Greenberg by name, but I had just read ‘Art and Culture’, and so I saw where all of it was coming from. Clearly a cheerleader, he changed the Advanced Course for us; even the French students, who kept us all at arm’s length, found him engaging, and he got everyone working. Richard Long and Hamish Fulton tried to take him on; Long called the St Martins style ‘Mannerism’, and Caro, disarmingly, agreed, to the annoyance of the ‘Basement Boys’ – by which I mean Peter Hide, and the others who worked out of the basement studio, producing work in steel that showed signs of Caro’s influence. We, the new intake, avoided them, and they avoided us.

During a crit of my work, Caro said to me, sotto voce, ‘You are going to be very good!’ To which Peter Hide snarled: ‘Don’t get too good.’ Caro could charm; but beneath the charm, myself and others could detect something of a perfidious character.

MD: How did Caro approach the teaching of sculpture?

DE: Perfidious character or not, and despite having a reputation for aggression, and despite Greenberg’s description of him as ‘a man on the make’, he had the necessary charisma to motivate students. He ran experimental classes, quick and exciting, with lively discussions after each event; and I am assured by David Annesley4https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/david-annesley-650that Caro himself was making ‘fuck-around sculptures’, of the sort he encouraged the students to attempt, in the privacy of his own studio.

I was once shown a letter Caro had written for a job application to the RCA, in which he had listed the tasks he set in these classes. Remembering one of them some years later, I tried it out on forty graduate students at the Hangzhou Academy of Art in China: ‘Imagine you are a fly on the ceiling. Make what you see.’ The results were fantastic; those Chinese students certainly knew how to model in clay. What you refer to as ‘Caro’s revolution’ was, from all accounts, derived from those early ‘fuck-around’ classes.

MD: What was the thinking behind Caro’s introduction of ‘The Forums’?

DE: The idea had been mooted that the Main Hall at St. Martins should be a Sculpture Centre; and this idea kept everyone busy drawing up plans and concepts for exhibitions and events until one sculpture student, whose father was a union boss in the Midlands, scuppered them. He and the Student Union successfully argued that the hall was for students, and not for an elite faction.

Nevertheless, the Forums took place in the hall and were open to all. It was intended that professional artists would bring work into the hall and leave it there to be seen; and then, at an evening session, it would be available for comment and criticism. The Forums attracted a good-sized audience, and plenty of participation by artists, as the opportunities for getting modernist art shown in London were drying up. I was pressed into being the subject of the very first Forum, and Caro was the subject of the second.

MD: Were they the breeding ground for the ‘bullying and intimidation’ you alluded to earlier?

DE: I, as the artist, was not expected to give a talk; the work was there on show, with Alan Gouk acting as Presenter. There would be an initial response from someone, and then a follow on, and on, so that one topic or line of attack led to another; and then everyone would feel emboldened to have a say. It was hard, as most of the comments were negative and few would dare to say anything encouraging. I remember little of the particulars of my session; only a general consensus that I needed to let go and not hold back in my work. I had never had such a grilling, before or since; and on my walk back home needed to call in at Westminster Cathedral and listen to Medelsohn Bartholdy organ music in order to calm down.

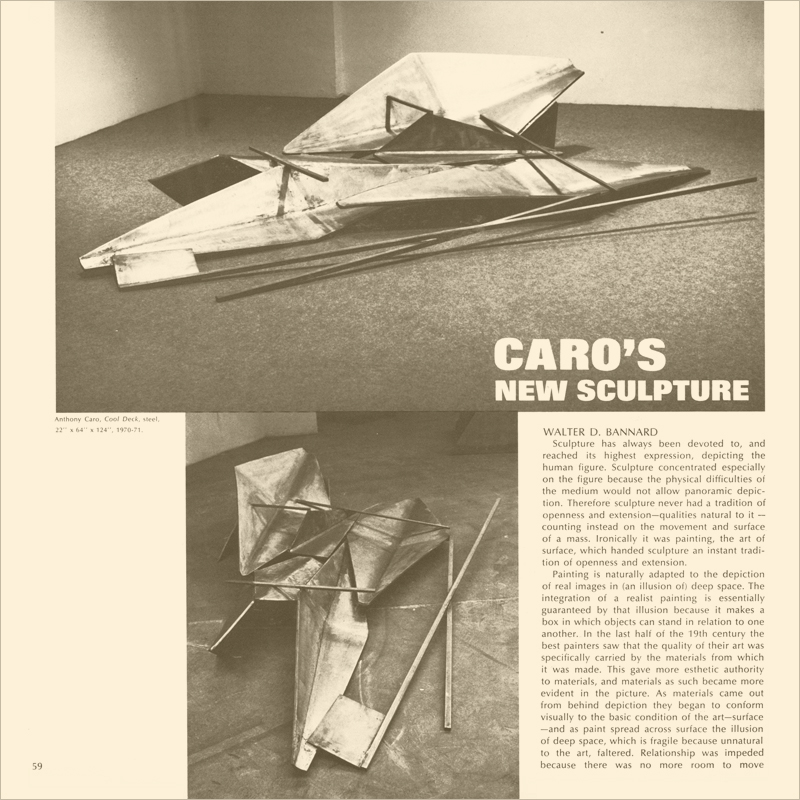

The atmosphere of the second Forum, with Caro as subject, was more respectful. One work he showed had used some of the stainless steel rhomboid shapes that David Smith had welded in preparation for new sculptures, and which, after Smith’s death, Caro had shipped over from the hills of New York State to London. Caro had cut off the sharp and pointed ends from these elements and arranged and welded them together on the ground; and to me, and to a few others, it looked exciting but neither resolved nor fully finished; something was missing. Some said they could not see it as sculpture at all; and most thought it looked plain weird. As it turned out, he took the work back to his studio, welded simple, low-slung additions across it, and in this way ‘Cool Deck’, a masterpiece of 1971, was completed. Caro had used the Forum to trigger his imagination, by getting a new feeling for the work.

Michael Fried was teaching one day per week for two terms; and his critiques at the few Forums he attended were listened to with serious attention. To give an example: Brower Hatcher had become very popular with his ‘hedge-like’ objects, using bent and twisted pieces of coloured wire so that colour floated in space. Fried found the combinations too sweet, relying on yellow and light-toned effects to set off the brighter passages.

Painters, as well as sculptors, also subjected themselves to these grillings. John McLean managed to survive his by getting drunk beforehand; but one painter, who shall remain nameless, was so disgracefully taken apart that he suffered a nervous breakdown and quit painting altogether. It was the time of Mao’s feared Red Guards; and I could not help but notice certain similarities with the behaviour of certain parties on the faculty and amongst the student body. Caro came around to thinking that the Forums had gone too far, with everyone licensed to have a go; but at least he had managed to use his session to help himself find a spectacular solution to imposing totality on a seemingly impossible abstract sculpture.

The atmosphere of aggressive discourse was thickened further in 1980, when Tim Scott took over as Head of Sculpture, and started a course in figurative constructed sculpture which he nevertheless insisted was not that, but rather, ‘from the body’, as he put it. It went well with the advanced students, and on the two occasions when I visited, the atmosphere was alive, very motivated and productive, with models holding difficult poses. However, it was not a success with the BA students; Scott had a reputation for bullying those who could not grasp what the staff were on about and had to endure it until they ‘understood’. After a short period his BA course was reviewed by an external committee and was not allowed to continue any longer. Scott had to resign.

MD: Your own encounter with Greenberg happened at the time of his 1970 visit to London, during which he lectured at St Martin’s; he reacted very favourably to your work during a visit to the studios at the Stockwell Depot. What can you remember of the visit?

DE: Greenberg came to Stockwell Depot at Caro’s prompting. Later on, I heard that he hadn’t wanted to come, as we were deemed too young. Caro had visited before, and he was supportive of our cooperative studio setup, the first in London, as it gave him access to younger sculptors. Caro had been dismissive of my efforts, which had hurt, of course; but I had been five years in art schools, getting a lot of stick, and had learned to filter out many of the comments that came my way.

Whilst others would waffle, and one would forget what they had said, Greenberg’s one-liners hit the nail on the head; as has been reported by many artists whose work he critiqued, one remembered his words. I have watched him in the studio with others’ work: in front of the work, it either hit him or it didn’t. No pause for thinking what to say; it just came out. Other critics have attempted to copy his approach, but without Greenberg’s level of experience, they can’t really be believed. Every decision made in the work seemed to count for him. How does one know? One just feels it. And this will be where I elicit sniggers from anyone who reads this.

There were six of us, traipsing around the studios behind Greenberg and Caro; and to each of us, Greenberg had something to say. To Roelof Louw, who showed a minimal steel piece indebted to Judd, he said ‘Any old American can do that; it’s arts and crafts.’ Of Peter Hide he asked, ‘What is so special about right angles?’ and got back from him an answer about Mondrian that didn’t go down too well. To Roland Brener: ‘It’s too long, it would be better cut in half.’ All of which sounds very flippant, the sorts of comments that could be made by anyone with a modicum of experience in contemporary art, but he was addressing the art, and his comments had weight because he had weight, and they were delivered in such a matter-of-fact manner that one had to take notice.

I had three large sculptures I wanted to show. At first, he didn’t say anything; then, going over to a work of mine in an adjacent space, said ‘I thought there might be something good here.’ Returning to the three I had wanted him to look at, he was silent again. I said of one of them: ‘Kasmin has bought this.’ To which he replied: ‘Well, I never thought Kasmin had an eye.’ At which point Caro shouted ‘But he shows my work!’ That broke the ice, and Greenberg went back to look again at the sculpture in the adjacent room, remarking ‘I don’t like the slates’– grey roofing tiles I had filched for inclusion in the sculpture.

He was taken with the works that featured an empty centre. I had been very interested in looking at Olitski, both at Kasmin’s, and in reproduction; my work had this separation of top and bottom I had derived from his painting. And we were all reacting to Minimal Art- Judd, Morris et al– and I wanted, in one piece, to contrast the difference between shapes below the ‘cage’ and above it. The metal was light, and galvanized; and the wood shapes a dull black. The largest, unfinished work interested him enough to ask: ‘Will you put something in the middle?’ ‘No’, I replied, gaining in confidence now. At which point Greenberg announced, ‘I’m learning, Tony’, and that was all. The visit to six studios had lasted thirty minutes in total. Brener was pleased, saying it had changed his life; Hide was cross; Louw dismissive. As for the other two- Roger Fagin and Gerard Hemsworth- I don’t remember.

MD: You have said elsewhere that it was thanks to Greenberg’s interest in your work, and the glowing appraisal of it that he gave to various important players on the London art scene, that you were offered a show at Kasmin’s that year.

DE: Waddington Gallery had already taken on many of the ‘New Generation’ sculptors; and I’m pretty sure Greenberg must have talked to them and to Kasmin about his visit to Stockwell. Kasmin had bought one each of mine, of Hide’s, and of Brener’s, which he exhibited at ‘Prospect ‘69’ at the Düsseldorf Kunsthalle, mine in his booth, the others on the terrace. These works were vandalized during a Neo-Nazi demo, which the German press hushed up; so, alas, no fame was forthcoming. Kasmin then told me that he would give me a one-person show; he bought more of my sculptures, so I could quit my job working at a playpark in Deptford. When I told the others the reaction was stinky sour. Artists are jealous people- myself included- and some sculptors can be fierce. What had been a cooperative venture at Stockwell Depot became a standoff between those who resented me and the few who supported me. None of the former group came to my opening.

MD: How did you feel your association with Greenberg might be perceived?

DE: In the small world of sculpture dominated by St Martins, the support given by Clement Greenberg counted as an asset. As I got to know more and more artists on the London scene, it became a liability. The winds of change were blowing over from New York, and the maxim, ‘If Greenberg likes your work, it’s the kiss of death’ was often heard. His followers and friends in high places were known as ‘The Gang’. The students and followers of Beuys I met in the Konrad Fischer Gallery, Düsseldorf, in 1969, were polite and not in the least arrogant, but when I said I would like to be as rich and famous as they were becoming, but that I needed time to develop, they could not believe it; they were amused that I still considered myself a beginner. And when I mentioned Greenberg, they reacted like Dracula to a crucifix!

MD: Were you aware then- or did you subsequently become aware- of Greenberg wielding the power to make or break an artist’s career, deliberately or otherwise?

DE: Did Greenberg have power? He had friends in high places, such as William Rubin, Director of MOMA New York, who was known as a member of ‘The Gang’; but Greenberg essentially wrote for specialised journals. Critics such as John Russell, or Hilton Kramer, at the New York Times, had much more influence. Yes, he was instrumental in ‘breaking’ Theodoros Stamos, who had fallen from grace over the Rothko scandal;5‘The Rothko case may be rarely mentioned nowadays, but there is little doubt that it had a lasting effect. For nearly a dozen years beginning in 1971, the art world and the public were transfixed by the battle between Rothko’s executors, all of them his good friends, and his two children, who accused the executors of waste and fraud, and by the ensuing appeals and related litigation. As a result, many of Rothko’s luminous Abstract Expressionist paintings, which had been sold or consigned by his estate to the Marlborough Gallery in Manhattan at deflated prices, were donated to museums, probably enhancing their value.

Rothko and his work became better known, further establishing his reputation. Marlborough lost its pre-eminence in contemporary art. Its flamboyant owner, Frank Lloyd, never recouped his reputation, and neither did Theodoros Stamos, a painter Rothko chose as an executor.

Before Marlborough was stopped by a court ruling, it had sold more than 100 paintings — including a few that Rothko’s children now say they would have kept — at less than market value to favored clients while it collected inflated commissions as high as 50 percent, compared with the 30 percent usually charged for an artist of his caliber. The executors, meanwhile, divided the estate’s proceeds from Marlborough as their fees.

In 1975, a New York State court ousted the executors, cancelled their sweetheart contracts with Marlborough and fined them and the gallery $9.2 million.

Later, while at his home in the Bahamas, Lloyd was indicted by the Manhattan District Attorney for tampering with evidence in the case. He surrendered after years as a fugitive and was convicted on three counts in 1983.’

The New York Times, November 2nd 1998but he then changed his mind and apologised profusely, saying that he had missed what was good about the paintings. He ‘made’ Caro’s reputation in New York, and he helped me get started.

His fall from grace- when it came- had a great deal to do with the scandal that blew up around his decision, as one of the executors of David Smith’s estate, to remove the paint from a batch of Smith’s sculptures and allow them to rust from ‘intentional neglect’. This was all unfavourably chronicled by Rosalind Krauss, who had been his favourite critic amongst his acolytes, before their spectacular falling-out. Neither Greenberg nor Motherwell, his fellow executor, had been asked by Smith to perform the role; Motherwell did little, and so it fell to Greenberg to make an inventory of all the works installed at Smith’s Bolton Landing studio and in the surrounding land for the tax authorities, who wanted an astronomical amount of money. Noticing a few recent works outside that were painted white, he decided to take them back to the raw steel, as the white was merely a dull undercoat that Smith had applied, (intending to add a finishing coat of lacquer), and beneath it was a rust-inhibiting red oxide primer. Paint stripper was used, and there was no damage to the steel; I know this for a fact, as a friend of mine carried out the work. As I mentioned earlier, Caro bought most of Smith’s leftover steel and shipped it back to London; while Greenberg went on to make a good deal with the authorities, making sure that Smith’s little daughters inherited well, and worked long hours at that cold comfort farm, because he loved the art, and Smith was ‘his’ sculptor.

Nevertheless, Krauss got her revenge on her former mentor by giving her version of these events. Greenberg was almost broken, claiming that he lost friends as a result; and the sculptures have since been painted white again.

MD: Greenberg’s ‘fall from grace’ seems to have coincided with the onset of a wider crisis of confidence in the late-modernist project that he argued so forcefully for; and your description of the upheavals both inside St Martins, and in the art world beyond it, also gives a strong sense of a system edging closer and closer to a point of collapse. Is this a fair reading?

DE: In many ways, yes, it is. By a certain point in the 1970s, it became clear where things were heading; and Frank Martin complained that Caro had become overly critical, negative, and downright nasty about what was going on. Caro couldn’t engage at all with the students who were introducing elements of the postmodern into their work; an intellectual he was not. His ‘solution’ was to make copies of the ‘Bennington Seminars’– a series of lectures that Greenberg had delivered in 1971, examining positions in contemporary art- and distribute them to all and sundry; and to then organise a seminar about them, with John Golding and Leslie Waddington presiding. Neither of them had any experience of dealing with students at this sort of level, and both clearly felt uncomfortable. The seminar was a flop.

As of 1973 I had taken up a teaching post within the Sculpture School; and myself and Bill Tucker dealt with second year students that he had previously declared ‘unteachable’ on account of the avant-gardist teaching programme they had undergone in their first year. They had been forbidden to talk and locked in a studio with nothing but a sack of plaster to work with; and all they had managed to produce was rubble. We soldiered on with them for two months, until a plague of mice, and an accumulation of wet, rotting junk caused leaks into the library below, and the Principal closed the studio down; Bill and I were lucky not to have been sacked on the spot. After that, it was decided to split the Degree Course down the middle, into A and B groups; the latter for those who wanted to follow myself and Bill in making sculpture, and the former for what I will describe as the ‘Sarah Kent Faction’,6Sarah Kent rose to prominence in the 1970s, first as Exhibitions Director at the ICA, and subsequently as art critic for Time Out magazine, and frequent participant in radio and TV discussions around the arts. She works extensively as a freelance editor, critic and essayist; a great deal of her writing has been for inclusion in catalogues and monographs produced by the Saatchi and White Cube Galleries.students that shared her regard for Josef Beuys, Richard Serra, Richard Wentworth, Arte Povera, et al.

MD: A schism had well and truly opened up between the Modernists and the Postmodernists?

DE: There had been various rather silly things made during the lifetime of the Advanced Sculpture course- George Pasmore’s fried eggs in plaster, Richard Long’s landscapes on bad vases, Bruce Mclean mime-acting ‘Early One Morning’– and the influence of Beuys’ Düsseldorf stuff, of Pop, of NeoDada, had been creeping in, not to mention John Latham’s chewing up and spitting out of ‘Art and Culture’7In David Evison’s words: ‘This performance was supposed to be followed by a lecture given by Latham’s wife to the faculty and student body; in the event, with everyone assembled and waiting, she declined to deliver it’; but yes, by this point, the reaction against what had been dubbed ‘St Martins sculpture’, of high modernist pedigree, was well under way.

MD: Did you have a sense of the Modernists- Caro in particular- fighting a rearguard action against the invading army of mime-actors and book-chewers?

DE: When Caro inaugurated the Triangle Artists’ Workshops in the early 1980s, he told myself and others- in so many words- that he hoped to use the Workshops as a means by which to counter what he saw as Modernism’s slide into Postmodernism; and of course, Greenberg was one of the star turns at these workshops. Young modernist painters and sculptors flocked to them.

Caro, I believe, was looking to find for himself in the Workshops what he had found in his experience of the Forum at St Martins: fresh inspiration. By surrounding himself with younger artists who were part of a milieu that paid close attention to Clement Greenberg, Walter Darby Bannard, and other ‘eyes’, and whose own eyes told them that Jackson Pollock and David Smith were the best of the best, Caro hoped to find his way back to that level of major quality. It was not to be.

MD: Why not?

DE: In part, because he had come to rely heavily, by this point, on an art market and a coven of collectors that approved of his endorsement of the new German school and the young British sculptors from the Lisson Gallery stable, and that approved of the direction he appeared to be taking in such works as ‘After Olympia’, which was his response to his visit there in 1985, during which he had seen the great pediment sculptures from the ruined Temple of Zeus. Back in his Camden studio, he had made a 25-metre-long transcription of the east pediment in steel; it was a huge mistake, and his art faltered, lapsing more and more frequently into what I would describe as the ‘Grand Manner’.

MD: When we hear that term, ‘Grand Manner’, we imagine an art derived from ancient Greek and Roman models of idealised form and expression, the kind that Sir Joshua Reynolds argued for in his ‘Discourses on Art’; inevitably, a figurative art. Are you saying that with the works of the 1980s, Caro ‘crossed over’ from abstraction to figuration?

DE: I’m saying that he had a certain talent for overdoing things. This talent found its expression in the ever-increasing grandiosity of his sculptural projects from the 1980s onwards: ‘After Olympia’, of course, and then the ‘Trojan War’, and then the colossal ‘Last Judgement’ at the end of the 1990s. If I describe this last work in detail, I will, I hope, give you more of the sense of what I mean:

‘The Last Judgement’ is an installation currently housed in Berlin’s fabulous museum of Old Masters, the Gemäldegalerie. It was bought by collector Rheinhold Würth. It is pretentious, pompous, and ugly. Traditional altarpieces of the subject illustrate both heaven and hell; but Caro just gives us hell. After fifteen minutes of it, myself and my companion had to repair to the permanent collection and look at Vermeer, Rembrandt, Titian and Raphael simply in order to cleanse our eyes; which also brought us face-to-face with the ‘Last Judgements’ of Fra Angelico and Lucius Cranach, both of which depict ugly scenes reinforced by sombre colour, contrasting with the light and delicacy of the place to which the blessed have gone. The paintings excite by the splendid drawing of the figures, by their colour, by the atmosphere they engender, and by their rightness, their sheer excellence as works of art. Great art has emphasis, which clings to it like mother of pearl clings to an oyster shell, and they have it. Any comparison with the Caro is, well…

‘The Last Judgement’ is extremely theatrical. The ninety-by-thirty-metre gallery is painted black and the fifty-by-twenty-metre installation stood on a dark grey raised platform on which one was permitted to walk, around and in between the work; very much a Curator’s intervention, I think, something they are wont to do. The colouration of the twenty-eight separate standing component works, meanwhile, is very much Caro’s own; and, lit with subdued LED spots, the brown, beige and grey give a sinister and ghostly feeling to the whole.

There are over-life-sized boxed and free-standing heads and body parts, many incorporating steel forms seen in previous sculptures; and hand-made, quasi-figurative stoneware shapes that contrast with the work’s massive wooden beams. Most of these elements would have benefitted both from having half of their parts removed, and from the work’s framing being eliminated, so that at the very least, we would be allowed access to the sculpture hiding behind it. As I recall Hemingway saying to a young writer: ‘The more damned good stuff you cut out of your novel the better it would be.’ Indeed.

At one end stands ‘The Bell Tower’; at the other, ‘The Gate of Heaven’. And here are the work’s redeeming features: at the ‘Gate’– which invites entry whilst simultaneously forbidding it- a flash of humour, in the form of large stoneware middle-body parts with real hunting horns sticking out from them, one blasting from an anal sphincter. And the ‘Tower’ is magnificent, with its bell and thick lanyard. This is what Caro is good at. It is direct and simple, possessed of a delicate weightiness, as though put together by fingers rather than forklifts.

MD: That aside, though, Caro’s re-engagement with the figure, and with all the ‘props’ of the Western tradition in figurative art, marked a falling-off in the quality of his sculpture from which he never recovered?

DE: I cannot share in the general consensus that Caro continued to be a great sculptor after his -admittedly magnificent- Andre Emmerich exhibition of 1970. He continued, with more downs than ups, for the next several decades; but I acknowledge that in the ten years before that point, he created some of the best art ever seen in these islands, and I forgive him for the folly of his ‘Grands Projets’. And even though these gigantic installations must have absorbed most of his energies, he continued to make good modernist sculpture up to the end of his life; after his funeral in 2013, during the wake held at the Camden Town studio, I saw on a turntable, in a small room which his widow said should not have been open, a small sculpture made in copper, brass and steel. It was the most three-dimensional of any modernist constructed-type sculpture I have ever seen. I asked her if it had actually been made on a turntable, but her answer was no. This was, without question, a new and original sculpture dealing with formal problems he had not tackled before. We know too little of what might have been spirited away into storage.

MD: Clearly, you view the arc of Caro’s career as in some sense a cautionary tale; the moral being, look what happens when a major sculptor- and a whole generation of students and practitioners following after him- moves away from the tenets of High Modernism.

What part has a continued commitment to Modernism played in your teaching? And in the teaching work of your contemporaries?

DE: For me, Hans Hofmann set a standard in Modernist teaching that has hardly been bettered; and my ambition was to follow in his manner with sculpture. But I was dreaming; in 1985 there was a big show at Martin Gropius Bau called ‘Die Neue Wilden’ (‘The New Fauves’), which was a huge success. Fame and acclaim followed for the painters in it: Kiefer, Lüpertz, Baselitz, all of whom featured in the Royal Academy’s ‘New Spirit in Painting’. Baselitz and Lüpertz went on to make chainsaw woodwork, and Kiefer branched out from two to three dimensions. That Berlin show caused standards to plummet in art academies; and my teaching had either to adapt or die.

Ambitious- and mercenary- students were attracted to my Klasse as it was lively; they wanted to do their own thing, which fitted in with the laissez-faire approach taking root in art schools everywhere. Beuys and his gang, working at the edges of sculpture, were claiming that anyone could do it. I had started as a Gastprofessor in 1984, taking over from Philip King,8‘Philip King had become head of sculpture at the RCA but did not have much influence there. He had been Gast Professor for two semesters at HdK Berlin, where he had energized the class and got them working in steel and constructing sculptures. King was, in my opinion, the most successful of the ‘New Generation’ sculptors; bringing a whimsicality, and a sound colour sense, to his work. His methods were traditional and laborious, polyester fibreglass poured into plaster moulds, requiring much sanding and polishing; and this before we knew anything about the health risks involved in those sorts of methods. King went on to be influenced by Minimalism which threw his quirky manner off course.’who had got the students all working in steel, well-financed, courtesy of the West Berlin money tree. This development was picked up on by journalists and critics, because in Germany abstract steel sculpture was at that time widely seen as a novelty.

The Wall was breached in 1989; and straight away students from the defunct GDR came knocking on my door. I enrolled some; they could at least make sculpture, even though they had no interest in continuing in their previous manners. I had learned to accept students’ ideas, whilst at the same time demanding of them ‘But show me what you mean!’ I saw my job as accepting what they were trying to do, in the hope of making them do it better. I am not too proud of that stance, as their starting points were unfailingly ridiculous; the goal of the new, of newness, has become institutionalised since Pop Art, perhaps before, and newness has become confused with originality. Nevertheless, the results have gone down well, and it seems that I have been fortunate enough to have overseen one of the most successful Klassen in Germany.

Now that two of my ex-students are Professors at UdK Berlin, it gives me the opportunity for contact with 30-year-old hopefuls. I have always liked to keep in touch with younger artists, and in Germany I have that opportunity, as many of those I taught are sculptors now.

As for my contemporaries: in Canada, Peter Hide and Terry Fenton had the advantage of the seclusion of provincial Edmonton, leading young sculptors into work that derives from 17th-Century German wood carving, but made in steel. I saw this work, all disparate pieces of steel joined together, at Triangle, and at the Barcelona Workshops. For me, however, it feels as if Hide cloned his students, and in my experience that tends to mean that their development is arrested; in German academies this sort of thing was and still is common, which is why Hofmann, all too aware of the risk of imitation, never let students into his studio.

Tony Cragg and Richard Deacon both ran Klassen at Düsseldorf Kunstakademie. They do not seem to have followers; perhaps that’s because they, and the other ‘New British Sculptors’– as they were once known- are now themselves The Establishment, a mixture of Knights of the Realm and Dame Commanders, and all of them RA’s; and so, the younger generation see their work as a retardation of sculpture. My own take is that their work shows nice polite taste, comfortably situated within the British Grand manner. In Berlin, Professors Olafur Eliasson and Ai Wei Wei have followers; but anyone looking to follow their example needs to have lots of money even to try it on the cheap. And in the USA, I am not aware of many sculptors holding sway over the younger generation, at least, not through teaching; Jim Woolfe and Michael Steiner have never taught. In Manhattan, Garth Evans and Lee Tribe, under the guidance of Bill Tucker and Willard Beopple, have influence at the New York Studio School.

MD: What do you see, when you look ahead? Do you have a sense of where sculpture- at least, the sort of sculpture that takes its cues from High Modernism- might be heading?

DE: Predictions about future developments for sculpture are a mug’s game, but some try. If I had to make a prediction of my own, it would be for sculpture that builds on the discoveries of Analytical Cubism; not the heroic failure of Picasso’s ‘Head of Fernande’ of 1917, which remains a traditional portrait bust, lacking any sense of openness, but the success of his adaptation of collage into constructed sculpture, starting with the Guitars. In the UK, Tim Scott9‘Scott had always shown an unusual sensibility, a predilection for dramatic differences of proportion which came to prominence in his ‘Bird in Arras’ series, sculptures which challenged Caro’s pre-eminence in the wake of his success in New York. They were very expensive to have fabricated professionally; and he later disowned them as being ‘too architectural’, blaming the oil crisis for the funds needed for their manufacture drying up. He moved on into works made in thick transparent Perspex, with forged steel parts holding them together. I remember thinking that they were better works at the early stage, with opaque styrofoam standing in while he decided on the sizes of Perspex to order (and thankfully, the Perspex wasn’t that white material of nothingness which should be banned from all sculptors’ studios.’and his circle, Robin Greenwood, Katherine Gili, Robert Persey, Mark Skilton, Anthony Smart, all interest me, as they are taking their chances with the legacy of this small-part Cubism.

And then there is Robert Goodnough (pronounced ‘Goodnow’): a New York painter, well-known but not famous- he’d had a one-person show at The Waddington Gallery in 1975- who died in 2018. He had been one of the youngest of the Ab-Ex generation of painters, and the only one permitted to observe and to write about Pollock at work in his Springs studio. He developed into a superb post-painterly Modernist; and on a visit to his New York studio in 1989, hoping to see his paintings, I saw that he had made a series of little aluminium-facet sculptures, using a quirky joining method employing tiny nuts and bolts. They derived from his paintings, which derived in turn from Analytical Cubism; and they were extraordinary.

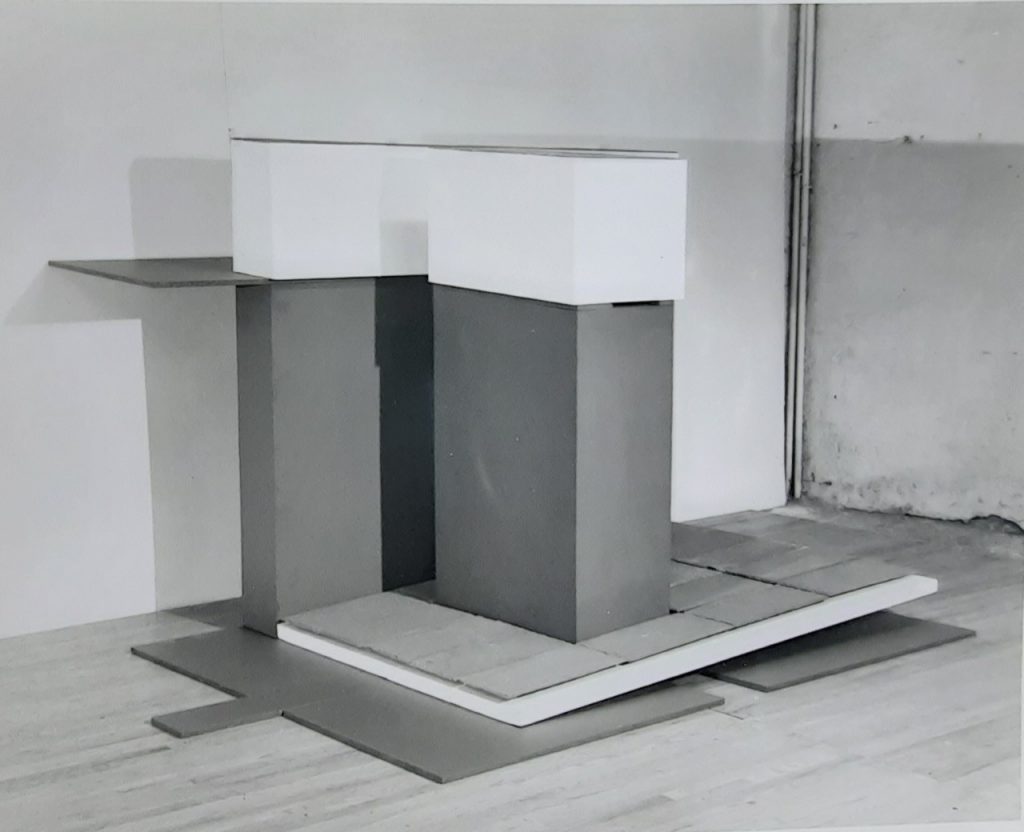

David Evison, ‘Southside’ (1988), steel, h 205cm

David Evison, ‘Whorl’ (2019), copper, steel, h 92cm

David Evison, ‘Pennant’ (2019-21), copper, steel, h 185cm

David Evison, ‘OT’ (2021), spray lacquer, crayon and pastel on paper

18 thoughts on “‘A Fly on the Ceiling’: Matt Dennis in conversation with David Evison”

Okay, there is a problem with this fly-on-the-wall, who-said-what-to-whom-where-and-when approach. However, David Evison is the only artist who instantly had the same scale problems I did with Sir Frank Bowling’s Tate show. It’s even more in evidence at Hauser and Wirth, with Poons and Frankenthaler round the corner. Tony Caro is yet to be appreciated, despite his terrible ‘Grand Manner’ shows. Two examples would be his chapel in Dunkirk, and the yellow perspex sculptures he was making when he passed away, both sublimely beautiful, not to mention ‘Early One Morning’ et al.I could offer my own version of what Clem said, but David Smith was a heroic figure to those who knew him, like Helen Frankenthaler, and was the reason I wanted to be an artist, to be like him. Nothing to do with the pecking order.

I am pleased that you agree about aspects of Frank Bowling’s work in his Tate retrospective, but it seems that we do not agree about that other Knight of the Realm, Caro. Unappreciated, you say? Mein Gott! He was given major museum shows around the world, funded largely by the British Council, to the chagrin of many artists of his generation. Not quite the household name as Holy Henry was.

To my shame I have not seen the Dunkirk Chapel. My excuse being always, too rushed to make a ferry booking or too anxious about the long haul East from Calais.

‘Early one morning’ I know well, and it diminishes each time I see it. It would be better diminished in size by compression; as would the coloured perspex sculptures shown at Annely Juda Gallery and then at YSP Wakefield. They should really be Naum Gabo scale – intimate and delicate. Again, the grand manner fails him.

Did you actually meet David Smith? A fellow student at Leeds College of Art wrote him requesting a job and received a polite reply saying he already had an assistant, and there were limits to his finances.

My congratulations to David Evison on such an honest and uninhibited piece. There are, however, some factual errors, which I’ll list; some of these are the result of playing a little fast and loose with the chronology.

John Latham’s book-chewing took place before 1967, ie, before Evison was a student, with Barry Flanagan as an active participant.

There were several exhibitions at Stockwell between 1968 and 1970, prior to Greenberg’s visit with Evison and the other sculptors; all chronicled with great accuracy in Sam Cornish’s book.

Greenberg never lectured at St Martin’s; and the only time he ‘lectured’ was at Goldsmiths in 1968, while he was in the UK for the ROSC show in Ireland. And it wasn’t a lecture. It was an informal talk, when he was subjected to hostile intervention from a Maoist student, on the issue of anti-Stalinism.

I took over the running of the Forums in 1967. As detailed in my account of the Forums in the pamphlet ‘Collaborating with Caro’, produced by UAL, Evison was far from being the first. It may well be the first one he remembers.

The seminar at St. Martins, devoted to Greenberg’s Bennington seminars, was a private one, with Andrew Forge, Golding, Tucker, King, Caro and myself. Leslie Waddington was not there. There were no students present, and I’m not aware of another one at which there were. Greenberg changed some of the seminar texts before publication as a result.

One other detail. I find it hard to believe that Caro ‘endorsed’ the new German school. I think Evison has got his wires crossed there.

Apart from that, I agree with much of the stipulation about Caro’s decline, which for me set in post-1972, and progressively thereafter. I echo his sentiments about the Greek pediment transcriptions, and many other later sculptures, regarding how hollow, pompous, empty and ‘formalist’ they are, and how awful ‘The Last Judgement’ is. And yet I remember Norbert Lynton saying to me how magnificent it looked in its setting in the Arsenale in Venice. There is no accounting for misguided taste in this world.

I have explained my responses to these works of Caro’s in my two articles ‘Steel Sculpture 1 and 2’ at AbstractCritical. These, unfortunately, can no longer be accessed online; but I have seen to it that the Brietman Archive at the Tate have digital copies of all my articles.

I am sorry I gave the impression I was present at the book-chewing performance by Latham. I was in Leeds. But I was present when his wife came to give a talk at St Martins and refused to give it before the assembled throng, only to tell us she would be happy to meet us in the pub.

There were no exhibitions at Stockwell Depot prior to Clement Greenberg’s first visit in June 1968- period. Sam Cornish’s sources of information are suspect.

The Forums in 1967? You had not started to teach at St Martins before 1970, as you have stated. I was not present at any Forums organised by Jeremy Moon and neither were you. In my recollections they started after the sculpture department tried and failed to get the Main Hall as a sculpture centre, but were able to use it for short periods . I was indeed the first of these and am not making it up. I did not keep a diary at that time but my memory serves me well.

A private discussion about the Benningto Seminars? First I have heard about it. Well, it was private. The student seminar with Caro, Waddington, and Golding also included David Mirvish (Toronto Gallerist and collector). You were not present.

My verb ‘to endorse’, is too strong. The German art world gossip was that Caro was ‘interested’. After all, he had major collectors in West Germany.

However one wraps up the events of this period, one cannot deny the optimistic, open-ended approach to sculpture’s development in that period.

My generation were very critical of what had gone before, but it is a testament to its quality that it could withstand such critical pressure from a new generation trying to move on; for example, that Caro’s and Smith’s sculpture seemed to embrace a certain flatness. It being that generation’s strength, it became the following sculptors’ foothold in prising open the potentialities of a greater deploying of the assets of sculpture in a more three-dimensional form.

Seeing again the sculpture of David’s from 1974 I am reminded of how much more physical and subtle that piece is than the memory I have carried of it. Also more recently seeing again his sculpture in the Stockwell Depot show in Greenwich, and being shocked by its ‘out there’ nature and having no problem with its physicality, which I had previously had thought I did.

Nothing is more harsh, in my opinion, than coming face to face with someone else’s sculpture that is seemingly doing what you are trying to do. But better!! (Of course, worse than this is seeing one that you had never dreamt of, and finding it very convincing.) That is tougher than any words ‘about’ a sculpture, because good sculpture is real!!

Thanks for this comment, Tony. Very generous of you. I respect a man who is able to change his mind and state it openly.

When you left St Martins and went to work at Stockwell Depot, you were involved with Peter Hide, Katherine Gili and Mark Skilton, in a reaction against the Modernism of your predecessors and myself. Fair enough. Art has developed that way before, as it did with Manet and Rodin. I was (and am) attempting to make my art completely three-dimensional, to look good from all round, and with abstraction we have a better chance to achieve this than there ever was with figuration. Not that we cannot learn from the masters of that form and from their failures. This is why I am interested in what you and ‘your group’ are doing. But not your theories and endless talk. Bitte! However, I keep a weather eye open, and it is more open than when I was 40.

Not replying to anyone in particular, but I want to correct what I said and implied: that Greenberg’s criticism of Theodoros Stamos was tied to the Rothko scandal. Piri Halasz informs me that Greenberg ‘scorched’ a Stamos show in the 1950’s, and it did indeed have a negative effect on Stamos’s career. The Rothko scandal was 10 years later.

Greenberg saw those ‘scorched’ paintings again much later, liked them, and realized he had been wrong. He went out of his way to say that publicly.

The best place to see Stamos is in Athens where he is revered as a major painter.

I will avoid Alan at his coolest, most factual and most dangerous. I have no knowledge of St Martins, nor would I attempt any comments. John Walker got me a job with Nigel Greenwood, who sent me to John Golding as studio assistant. He was more serious about his work than most others I have ever known. I met Mclean at the Serpentine, when he threw his stick at Tim Hilton, in the midst of a opening. It hit me and we remained friends for 30 years. I was living with Jenny Durrant and had a studio of my own in Warner Rd, Camberwell, a huge church hall. I visited Durrant and Mclean often at Stockwell in ’76, and was involved in critiques, which turned to violent melees at Caro’s comments. I can honestly say Caro changed my life in the most profound manner, as did Hoyland later, by choosing me for the first Triangle Workshop. But it was his friendship which made the most impact, going to the Met together to look at Dogon Sculpture. I find the competitive hatred amongst sculptors fairly extraordinary, as the enemy is the Establishment, the RA, not each other. We will all be airbrushed out of the history of English art shortly because of ignorance and elitism, and hatred of abstraction, which explains Sir Frank Bowling’s and my emigration, as well as that of Walker and Tucker, to the US. Helen Frankenthaler’s early work and Larry Poons’ mini-retrospective, next door to each other in London this week, could be from another planet, because of their extraordinary dedication and professionalism. By chance I turned to BBC4, where Pasmore was defending Caro over the affair of sixth-formers using his sculpture near the Hayward as a bike rack. The critics who should have known better, with their jolly-hockey-sticks, I-don’t-know-what-art-is-but-I-know-what-I-like, were shocking in their trivialisation of the art. This is the actual climate we have lived through, which continues to this day. Modernism, Formalism, are just terms of reference; incipient Fascism, Nationalism are not, they will attempt to destroy free expression, not just reputations.

The stick in question was thrown not at Tim Hilton, but at Patrick Caulfield. Why would it be at his close friend Tim?

I started ‘teaching’ in the sculpture department at St Martins in September 1967. My main role was to run the Forums, which had fallen into abeyance. I believe Jeremy Moon had been running them occasionally after Alex Trocchi was fired. I was also assigned a role with the first-year students to supervise projects initiated by Bill Tucker, who had just been brought in from Goldsmiths to shape up and give intellectual pedigree to the newly formed Dip.AD course. The department was transitioning from the old NDAD course structure, to one with a bigger complementary studies and thesis component, and Bill feared quite rightly that this would lead to dilution of the sculptural content and political interference from the Complementary Studies Department, run by a lapsed Marxist, Simon Pugh, which was bound to expand at the expense of the main departments, and undercut their ethos.

Ideological differences gradually emerged with some teaching staff, chiefly Peter Atkins-Kardia, another Marxist, who had come over from Ealing College of Art, closed amidst some controversy years earlier. The Ealing boys, as Tony Caro called them, had been Harold and Bernard Cohen, Roy Ascott, Atkins-Kardia, and others. Caro disliked the intellectualism of their approach, its involvement with Cybernetics, semiotics, Norbert Wiener, etc.

And that is why the ‘A’ course was formed, as a splinter group of dissident staff, unhappy with the assumptions of the sculpture makers. Garth Evans, a friend of Tucker, joined the dissidents, along with Ken Adams, (Praveera), Peter Harvey and Gareth Jones. I think the first intake to the ‘A’ course was in 1971.

Tucker felt that you learned as a sculptor by making, and making mistakes, not by sitting and pondering the nature or viability of art. We Tuckerites felt that the ‘A’ Course was a dangerous experiment in sensory deprivation, and that its consequence was that students were drawn directly to the pages of ‘Artforum’, by this time a hotbed of ‘anti-form’, Land Art, Minimalism, Judd and Morris, aleatoric John Cageism, etc., in search of guidance; and so it proved.

The only ‘A’ course students I can think of who remained with the course are Richard Deacon, who became a fully-fledged Tucker-type maker after leaving; Tony Hayward, and Roderick Coyne. After one year students had the option to transfer to the ‘makers’, the ‘B’ course. This is what Jeff Lowe and Lee Tribe did. The ‘A’ course negotiated a different form of assessment from the ‘B’: there was no degree show, but a form of continuous assessment, carried out by people sympathetic to the aims of the course. Who these people were, I have no idea.

In 1967 I was never sure which course the older students were on. It was only when I was asked to take over the Advanced course in 1970 that I knew, because I had been involved, and became more involved, with selection. Which course were Gilbert and George on? or Richard Long, Hamish Fulton, Tim Head, Victor Burgin? They were all present at that time, and soon to become luminaries in the rebel camp, and therefore gleefully taken up by the curatorial consensus.

So, Tony Caro was incidental to the ongoing politicking within the department; and Greenberg never entered the building. He did, however, take part in a panel discussion on the role of criticism at a venue in Great Queen St., near the Connaught Rooms, sometime in the early seventies. Richard Hamilton declared that Greenberg wasn’t a critic, but just a tipster. Someone else then spoke. I think it was Richard Cork, but can’t remember anything he said. Greenberg then launched into a highly personal reminiscence about his relationship with Pollock. Barbara Reise, speaking from the floor, raised the issue of the paint stripping from the Smith Sculptures, which had been in the magazines. Greenberg replied: ‘Lady, you’ve got a dirty mind’. And that was it.

The argument was really about the fundamentals of an education in art. We, the Tuckerites , felt that, as Caro later put it, ‘We’re going for a swim, and you’re talking about H2O.’

It’s interesting that all the main ‘makers’ were university educated, intellectually aware; King, Tucker, Tim Scott, and myself, who had come to art, not through the art school system, but from a need to get away from academia and the cerebral approach; whereas the ones who would later be designated as having a ‘conceptual’ orientation, were for the most part products of the English art school system.

It cannot be stressed enough that the Advanced Course in Sculpture operated without any official sanction or backing. It had been turned down by officialdom more than once, but Frank Martin was able to persuade the Principal, Edward Morse, a fellow military type, to allow it to continue.

It was thus able to recruit students solely on the basis of proven talent for making sculpture, regardless of academic pedigree. Some students were genuinely postgraduate, but not all.

There was a useful link up with the British Council’s Foreign Government Scholarship Programme, so that they were happy to be able to place students from all over the world at St Martin’s (and elsewhere). This may account for the steady flow of Israeli students, the stone carvers of lore. There is also the South African connection, and the Latin American contingent. That is how Annesley and Bolus came to be there too.

Caro would come in one day a week, and roam freely between diploma and advanced students, though primarily with the advanced, before coffee break, when it would be agreed which pieces of work should be ‘critted’. These were group discussions, where everyone would have a say, initiated by the student. But no one was allowed to grandstand or bore. Of course they were stressful for the student, but also illuminating and exciting. Some staff, on the sidelines, resented these intrusions, and felt that there was an element of coercion involved.

Frank was persuaded to put Barry Flanagan in charge of the Advanced Course in 1969. He lasted one year: it was a disaster. Barry’s approach was one-to-one contact only between staff and students, thus reversing everything that had made St Martin’s work. Students were offered a parade of contradictory advice, and polite encouragement from visiting lecturers, cubicle style, no audience intervention, like all the other art schools around the country, and left to make sense, if there was any, out of all the contradictions.

So that is how I came to be invited to run the advanced course in 1970.

The story of the Forums I have detailed briefly elsewhere. But a couple deserve particular mention:

John Panting, around 1972, was invited in, or volunteered, from the Central School, as a challenge to the prevailing assumptions at St. Martin’s. (Whether Caro was present I can’t recall.) The consensus at his forum was that his was not sculpture, but graphic or architectural design projected into 3D. Long sections of steel bar flex under their own weight, and this gravitational pressure should be sensed and dealt with in the work. Panting had dealt with it literally, by using excessively thick bars, which gave the work the look of architectural furnishings. It was not ‘physical’ enough, did not engage with the material. This blunt appraisal had a remarkable effect and brought about rapid change in his work. Before his untimely death in 1974, Panting had become one of the most exciting sculptors around.

Carlos Grainger had been working with Caro, helping to build and paint his sculptures. Grainger asked to bring in his own recent work; these were long, shoulder-height, abstract, bookcase-like steel constructions. Caro was furious, since they were a rip-off of the very pieces that he, Caro, was working on at Georgiana St; prompting him to immediately arrange a showing of these new sculptures at Kasmin’s Gallery.

As is well known by now, Tucker and Caro didn’t get along. Tucker’s book ‘The Condition of Sculpture’, 1974, apart from anything else, is a skilful demolition of the Greenbergian view of modernist sculpture, of the concept of ‘opticality’, of the idea that modernist buildings can be turned upside down and remain the same, and much more besides. It attempts to define ‘what sculpture is’, and what it is not. How he persuaded the Arts Council to let him mount an exhibition on that theme is a mystery. It certainly couldn’t happen today.

Of course the Arts Council immediately set about reversing course, so that a few years later they staged ‘The Changing Condition of Sculpture’, curated by an ex St. Martin’s student, Yehuda Safran, which installed everything that Tucker had disallowed, following the Harald Szeemann triumph, ‘When Attitudes become Form’, which had been full of ‘anti-form’, Arte Povera, Fluxus, text-and-photograph, ‘non-medium-specific art’ as it would become, and all the rest of the detritus of the Scene.

Tucker followed ‘Condition…’ with two further essays, ‘What Sculpture is’, and ‘Space, Illusion, Sculpture’, which delineate and anticipate much of the debate about sculpture which still flickers on today. He then produced ‘Confessions of a Formalist’, in which cracks began to show, or (as Greenberg had put it, in relation to Pollock) in which it became apparent that there was ‘something soft underneath’. And so to today.

In my opinion there is much in all of this that still stands, with all the qualifications and addenda that I and others have contributed, and in spite of the ridiculous self-propagandising zeal of certain current practitioners.

The Triangle Workshops were a last-ditch effort by Caro to wrest the debate away from what was going on at Stockwell Depot, and from St Martin’s under Tim Scott’s lead, between 1979 and 1983, before the closure of the Degree course by the CNAA. The Greenbergian hegemony in the USA had come under serious strain from all sides. The various outposts at Edmonton, Saskatchewan, Emma Lake, were all that remained of the Empire, with occasional visits by Greenberg to South Africa, India, even Scotland. The motives of the participants in the workshops may have been couched as idealistic, but no doubt they also hoped that there was still something to be gained professionally, or that some stardust might rub off on them.

All that emerged, however, was yet another slipping and sliding 10th Street Mannerism. The farce of it all is illustrated by Larry Poons haranguing people: ‘You’re painting what you know. Paint what you don’t know’, whilst he himself arrived with a van full of buckets of gel, erected a screen around himself, and began throwing paint around, doing what he had been doing for a decade or more.

Shortly before the infamous visit by the CNAA Monitoring panel to assess the degree course, Adrian Montford, one of the old guard who had come over from the RAS school with Frank and Tony in the mid-fifties, and who had opposed everything progressive that went on, none the less was moved to say that he had never seen such a range and variety of work in so many different materials going on there. And yet the panellists declared the course to be too narrow ( ie. not a multi-media ‘Fine Art’ course). Sheila Cluett asked: ‘Why are only steel, stone, plaster, a paper, wood and clay being used for making sculpture?’ (ie., why no nylon thread, feathers, plastic bottles?). Fibreglass had of course been banned many years before as a health hazard.

And Ian Barker, no less, (what was he even doing there, as a gallerist with Annely Juda?) had this to say: ‘It’s like a course in arithmetic, but only one kind of arithmetic.’

Are there two kinds of arithmetic?

You have made many assertions here that are false. You contradict yourself when you state that you started teaching at St Martins in 1967, and then state it was in 1970!

Greenberg entered the old Charing Cross Road building on at least two occasions. He gave a talk in the Foyles annexe. Were you not there ?

I do not think our readers are much interested in this (or your latest reply). I am, and I hope they are interested in your take about the Forum where ‘Cool Deck’ was discussed; it became one of the most important sculptures of the 20th Century.

To repeat what I said in the article published in the UAL ‘Collaborating with Caro’ booklet, I started teaching at St Martins in September 1967. My main role was to run the Forums, and the first few were of former students who had recently left. They were done with slides. Bruce McLean, Ian Spencer, Wendy Taylor, John Hilliard (I think). I even did one myself, asking John McLean to share it.

There were visits to the Stockwell shows in 1968 and 1969, but whether they could be classed as Forums I don’t know. There was at least one that took place at Stockwell, featuring Peter Hide’s big clubfooted posts supporting a steel bar in literal tension, which came in for strong criticism. Caro was present. That must have been in 1971. Maybe yours was the first in the Main Hall, I’m not sure.

In 1967 I was also given a teaching role in the first year of the newly formed Dip AD., alongside Roland Brener and Roelof Lowe, who had also recently left. But by 1970 I was asked to run the Advanced course. Perhaps that’s where the confusion lies.

I’m happy to agree that the first exhibition at the Depot was in 1968. I was present at the opening, where I remember your sculptures in particular as being made largely of mesh cages, with overhead elements supported by the mesh. Was slate involved? Or was that 1969?

As regards the Bennington Seminars, we must be talking about two different occasions. The initial meeting was to give Greenberg a private response from informed ‘critics’, before publication. There was no audience. Andrew Forge, John Golding, Bill Tucker, (Phillip King?) possibly Norbert Lynton, Anthony Caro and myself. It was taped, typed up and sent to Greenberg. Subsequently, changes were made before publication.

This other seminar I know nothing about. Leslie Waddington and David Mirvish were certainly not present at the first one.

The only occasion I am aware of of Greenberg visiting St. Martin’s was in 1981, when he came in with Tony Caro to the main hall during the lunch hour to see the ‘Lion Project’. His comment – ‘it’s student work’- was of course true. Of course, as a part timer, I wasn’t there all the time, was I?

Terrific to see two artists like Alan and Tony being so supportive of David Evison, and hearing the factual history of St Martins. I didn’t get in, from Exeter pre-dip, which wasn’t a problem, because I had been taught by Dennis Creffield and John Epstein at Barry Summer School. Harry Thubron had us cutting into torn coloured paper whilst naked ladies wandered amongst us, and him leaning on his stick like Matisse. Bert Irvin, Basil Beattie, Andrew Forge were in the Queens Hotel. I went to Cheltenham in desperation, and was taught by another Marxist from Oxford, Nik Waite, who ran complementary studies from a cider pub. He introduced me to Godards’ films, and ‘ArtForum’. I was greatly impressed by Bill Rubin’s summary of Pollock’s work. It had fused the three most important 20th century movements, Impressionism, Cubism and Surrealism.The Painting School at Cheltenham was an awful soft touch to the RCA, and again fate intervened, as I went to Birmingham, the most exciting Painting School in the UK. Bill Gear was Principal, John Walker had just left, but his influence was everywhere. Mick Bennett and Dave Tabourn were pouring thick paint onto loose huge canvasses; Ron Piat was floating silkscreen inks onto shallow pools of water, imitating Morris Louis. Derek Southall ran the Postgraduate programme, and within weeks I was a guest at Heron’s Eagles Nest home, and then to South Carolina to meet Olitski. In NY, I visited Ronnie Landfield, and saw Caro’s ‘Veduggio Flats’ at Emmerich’s. By 1971, I had shown a 9′ by 12′ oil and acrylic mix at MOMA Oxford with Gary Wragg. My experience of Stockwell started in 1976. By 1979, I had a show with five others at the Serpentine, and a two-person show with Charles Hewlings at the ICA. I moved to Greenwich LEB depot, and Caro sent a bewildering mixture of celebrities, Peter Palumbo, Von Wenzell from Germany, Dennis Lasdun and his wife from the IBM Building ,Robert Loder. Adam Westerby bought my best work from Hoyland’s Hayward Annual. Matt Dennis and I have discussed the sea change that occurred in 1982, when Thatcher forced me to emigrate to N.Y. Just a few misconceptions about sprinkling stardust. Caro got me to build a space for Triangle on Grand St in NY, and rewarded me by inviting me to the 1986 Triangle Workshop. It all started to unravel. Something occurred between Poons and Hoyland in the bar and Hoyland then left for Jamaica. After dinner, Tony gave a speech in which he characterised myself, John Foster and Peter Hide as dinosaurs, who had failed to rise to the challenge of Postmodernism. This was in front of critics and collectors. We were furious and the three of us spent the next morning chastising Tony in no uncertain terms. I didn’t speak to him for some years after that. My studio in NY was shared with Bill Tucker and Lee Tribe, at Greenpoint in Brooklyn. I gave up teaching to work everyday in NYC, it was so magnetic. I only had one show at Hunter College, where I taught, in ten years, but my work progressed apace into 3D assemblages made of leftover construction materials, which I still stand by. I was close friends with Helen Frankenthaler and Stanley Boxer. At Hunter College, which was all about geometric abstraction, and met some terrific artists outside the Greenbergian aura. I was learning about colour. Formalism had gone into heavy greyness, gels and manipulation, as in the work of Poons and Olitski. I particularly enjoyed the work of maverick artists like Isaac Witkin, the sculptor, and painter Bill Jensen, as well as Ray Parker, Doug Ohlson, Sandy Wurmfeld. When I moved back to Devon on the death of my father and onset of my mother’s illness, I moved into Oval Works with John Mclean and Gary Wragg. Robin Greenwood saved my life by giving me a one-person show at Poussin Gallery in the mid 1990s. I have, incidentally, seen the best sculpture of recent years in his studio last week, while visiting his new space. He deserves a major retrospective at the Tate or equivalent space very soon. I would love a forum /discussion/debate around the three phenomenal shows of Lyrical Abstraction in London last week: Poons, Frankenthaler and Bowling. There is also Fred Pollock at Waterhouse Dodds, Steven Walker and Alan Gouk at The Cut in Halesworth. In other words, it isn’t over by any means. There is also the Caro Centre opening at Georgiana St. Robin Greenwood has a new list of exciting abstractionists, the Brancaster Chronicles continue online, we are remarkably resilient. History is still being made, the jury is still out…even on Instantloveland, Modernism isn’t dead!

I don’t think it matters much at this point in time what the order of events as and by whom and when is…but I would say that, be it as a student on the Advanced Course or as a teacher myself later, the real challenge was first in establishing the department as being ‘about something’ and, amongst other things, as being the challenge to new participants to maintain and further investigations into sculpture.

Throughout my own 15 years’ experience at St Martins, if asked who made the biggest impression and was the most outstanding teacher, it would be Alan, because he saw that what for you was a very ‘make or break’ piece of sculpture, that you would be working on at the time, could be seen in a much broader context, moving your horizons.

It was the quality of all the teaching, the quality of the students, and the quality of that commitment that gained respect and credibility for St Martins then.

I’ll keep this as brief as possible. Excellent contribution from David; the subtext is that despite all our thoughts about our work, and each other, we have been operating essentially without the support of commercial galleries, because of our passion for abstraction. My last substantial show that I enjoyed was in at Hillsboro in Dublin, with John Daly, who is professional and honest. He has shown John Gibbons and Larry Poons. My last London show ended up in legal nonsense, which has put me off big time; most galleries appearing to be dishonest and corrupt. I have just seen the best sculpture I’ve seen in quite a while, in Robin Greenwoods studio, with very varied elements. Meanwhile Philip King has passed away, as has Douglas Abercrombie. RIP, great gentlemen. Apart from thinking John and Matt deserve our support by response to and discussion of their terrific articles, there is also the utterly random nature of our careers.

It’s an interesting batch of reminiscences – but why are there no mentions of women sculptors? Katherine Gili is the only female sculptor who pops up. It shows again and again that the whole modernist era was totally impoverished by a lack of female voices. Women‘s voices were there of course, but they they were drowned out by cliques of men who felt entitled to dominate. What a sad waste of time as real progress can never be made with just 50% of humanity at the feeding trough.

Helen Frankenthaler should be added to your list of female modernist sculptors, and one can see one sculpture at Gagosian Gallery, Davies St, London.

I am disappointed that few replies to my interview with Matt Dennis have been about the sculpture I have mentioned.

This work by Caro, ‘Cool Deck’ is reproduced with a double photo and was in Artforum accompanying Walter Darby

Bannard’s 1972 article (which also can be accessed on Walter Darby Bannard-Archives). It has some of the most important

writing on modernist sculpture, as he analyses Caro’s art and hits the nail on the head as regards this great work of sculpture.

He writes about imagining the work without the crossed bars at the front, which is how we saw it at that St Martins

Forum. Michael Fried was not present that evening, but Caro explained that Fried had seen the work in his studio

and had suggested something was missing at the front. The delicately placed horizontal bars were there but no one

was able to come up with ideas, guesses or better about what could be added. Most were mystified, as was I, and

Alan Gouk, who was also present, had little to say that I remember.

I am aware of talk from sculptors about the need for modernist sculpture to be more three-dimensional. When I

asked Tim Scott for permission to reproduce a recent work of his, he sent me 8 views of the same work which looked much

the same from all around. And he, along with Gili, Persey, Skilton, Greenwood, and Smart, are involved

in making ‘small-part cubist’ sculptures, intending them to be more three-dimensional. The danger is that these works

become closed-facet sculptures, and therefore more traditional than the modernists they hope to supplant.

Darby Bannard gets it right when he describes ‘Cool Deck’, and how the crossed bars and large rectangle

up front take a closed-facet beginning into another world, the result of inspiration rather than deliberation. I most strongly

recommend the sculptors mentioned, and others of course, to read this article, and ponder it in relation to their own sculpture.