John Bunker: ‘Irreducible Determinations; or, Following the Fault Lines’

As galleries and museums start to reopen, I find my social media accounts ablaze with the euphoric outpourings of happy punters enjoying their first fix of art and culture in months… I, on the other hand, am not able to muster that kind of wide-eyed enthusiasm just yet. The last lockdown has meant I have not spent any time in galleries, looking at works of art, for over three months; and even before that, my one-to-one encounters with them were sporadic, hampered by an attention span reduced to a shrunken husk by ‘doom-scrolling’ my way through the previous year.

This enforced physical disengagement from real works of art has got me thinking about some of the preoccupations one brings to the act of looking at them. Absence may well make the heart grow fonder; but maybe this is also a time to reflect on one’s tortuous relationship with the love object.

Abstract art has been my obsession for many years, but only in the last few months have I become aware of growing tired of the way I’m thinking about it; my lexicon of phrases, my personal rhetoric, my use of ‘insider lingo’ (what a linguist might call a ‘restricted code’); series of words in a certain order, phrases composed of abbreviated terms shared between a group of like-minded individuals; a mixture of metaphorical nods ‘n’ winks, sidelong glances and polite anecdotal digressions.

So what is the nature of this growing ambivalence? What could I possibly mean by the term ‘abstract art’? And how could one generalise so wildly about it? Is not the term so contested as to become a meaningless catch-all? Aren’t there just too many controversial and competing histories? Each time I let myself dwell on these questions I feel a dark abyss opening up beneath me. The fault lines in my perception split open, and suddenly I am peering down into a chasm of confused and conflicted thinking onto whose great walls I find myself clinging. It’s not the art objects themselves that I am tired of, but the ways in which I think about them.

However, rather than attempt, for the umpteenth time, to extricate myself from these dark depths, I now want to descend still further, the better to understand the grating, oppositional movements of contrasting approaches to understanding abstraction’s history that have, both knowingly and unknowingly, given rise to the fault lines in my thinking that opened up this chasm.

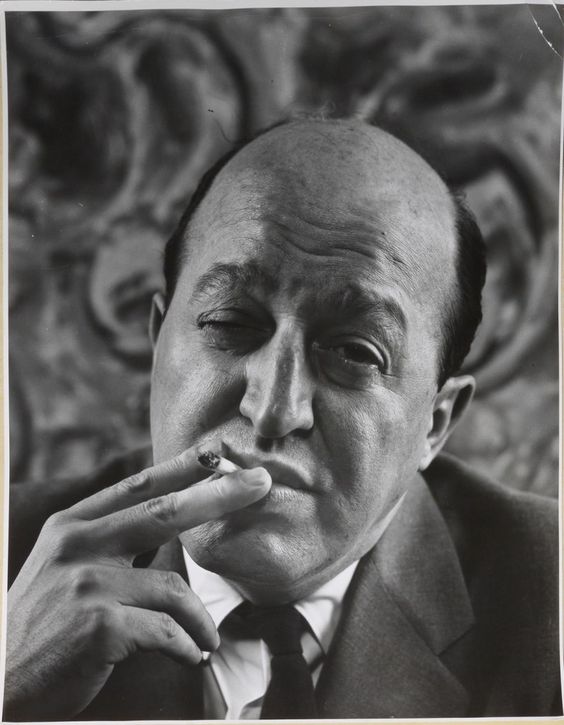

To do this, I will draw on two texts that both echo and examine the opposing forces at work in my conflicted thinking. They were both published in the 1990s; both of them looking back at abstract art as it was seen and argued over in the USA, in the years following the Second World War; both highlighting Clement Greenberg and his influence on the abstract art of the time, yet having radically different things to say about him, and drawing radically different conclusions. How far have things really moved on in our understanding of abstract art’s history from the 1950s, to the 1990s, to the present? Does Clement Greenberg really still exert a shadowy, pervasive influence on what I believe I want from the abstract art I look at? Do the opposing propositions outlined in these texts haunt my own way of looking, both at Greenberg and also at abstract art in general? Any answers I arrive at can only be partial and provisional; but nevertheless, it might be possible to use the contrasting outlooks of these two texts in a reflexive manner, so as to cast two different kinds of light back on a particular period in abstract art’s development, and forward on to our present tense; illuminating, in the process, the anxious questioning that lies at the heart of my ambivalence.

In his short but philosophically dense essay ‘What Is Abstraction?’, Andrew Benjamin uses Greenberg’s seminal texts as a jumping-off point for an exploration of the ‘almost primordial connection of painting and time.’ Benjamin describes how abstract art might extend itself through developing new relations with time and repetition, and in the process expertly meshes together key components of Greenberg’s assessment of abstract art’s defining qualities with his (Benjamin’s) own arguments concerning the limits of his (Greenberg’s) definitions. He connects Greenberg’s idea of how painting’s full self-realisation can be apprehended in abstract painting to what he calls ‘art’s work’, and thus, to the history of painting. Benjamin suggests that ‘even though Greenberg writes of a move away from imitation, this move should not be thought of in terms of negation. It is rather the identification of another source of signification. This source will be the object’s own work. For Greenberg this also resulted in the move to abstraction- in the minimal and thus negative sense- even though it can also be identified at work in ostensibly representational painting (Courbet and Manet). This identification of another source of signification comes to be linked by Greenberg to the immediacy, or ‘at onceness’, of the object and yet is not reducible to it. In arguing that sculpture and painting have a greater capacity to actualise ‘purity’ than is the case with poetry, this claim is presented as inherently connected to its mode of reception.’1Benjamin, A, ‘What is Abstraction?’ p13, Academy Editions, 1996

And, quoting Greenberg: ‘Painting and sculpture can become more completely nothing but what they do; like functional architecture and the machine, they look what they do. The picture or statue exhausts itself in the visual sensation it produces. There is nothing to identify, connect or think about, but everything to feel.’2Greenberg, C, quoted in ibid., p34

Greenberg, in Benjamin’s view, ‘maintained a politics of art that was linked both to the continuity of art and to the formal presentation of art work. This accounts for why abstraction is linked to a conception of autonomy that does not pertain to the artist but to art’s work.’3ibid., p27 But Benjamin also suggests that Greenberg felt compelled to suppress a level of complexity in order to secure an interpretation of the development of modernist painting that hinged on the terms ‘opticality’ and ‘at-onceness’.

Quoting Greenberg again…‘The latest abstract painting tries to fulfil the Impressionist insistence on the optical as the only sense that a completely and quintessentially pictorial art can invoke.’4Greenberg, C, quoted in ibid., p27 But Benjamin counters: ‘Opticality, at the very minimum, is a relationship between a subject and object. For Greenberg the subject’s response to “at-onceness” involved “freedom of mind” and “untrammelledness of the eye”. In addition, there is the assumption that the viewer is a unified singular entity which in a single moment confronts a work that is given in its absolute simplicity.’5ibid., p27

Benjamin focuses on the complex relationship between subject (us) and object (artwork), questioning the notion of ‘at-onceness’ that Greenberg demands as necessary to properly apprehend a successful modernist painting within the framework of opticality and the historical precedent set by Modernist art: ‘He [Greenberg] continues with the claim that “the picture or statue exhausts itself in the visual sensation it produces.” (1.34) It is this “visual sensation” that is given and received at one and the same time; there is nothing else, nor does anything remain, the object “exhausts itself”.’6Greenberg, C, quoted in ibid., p23

Benjamin queries Greenberg’s insistence on the individual’s ability to perceive an artwork with an ‘untrammelledness of the eye’, noting that the relation between subject and object is ‘complex’: ‘The subject’s position- the positioning of the subject- will itself be traversed by a number of irreducible determinations. What vanishes therefore is the possibility of there being a simple and thus undifferentiated subject as the foundation of subjectivity […] vision (or visuality)- the work of the eye- can only emerge as a question once the relationship between the subject and the object allows for the presence of a complexity that is marked by necessary irreducibility.’7ibid., p28

Not only does Benjamin define the subjective experience of an artwork as complex, but he also suggests that an artwork (the object) has a complex relationship with time, with history. Artworks are always open to new interpretations over time; and thus, they can also be seen in themselves as an integral part of ‘art’s work’, which can be understood as a process of giving foundation and ontological security to the art that would follow after. Moreover, ‘Instead of viewing each abstract painting as a unique and self-enclosed work, the work of pure interiority, there must be an allowance for the possibility that part of the work, and part of its own work as a work, will be a staged encounter with earlier determinations and thus forms of abstraction.’8ibid., p38

This term, ‘staged encounter’ is intriguing. But a ‘staged encounter’ might be understood to have other connotations, especially given that Benjamin is placing a powerful art critic as the central character of his narrative. Couldn’t this ‘encounter’ with history be a stage-managed encounter organised by an individual with their own particular agenda? Benjamin’s close readings of significant art objects and historical texts construe a sense of constancy within the art-historical continuum in which many abstract artists would like to place themselves, thereby enjoying a sense of purpose, and of protection from the encroachment of mass culture (what Greenberg originally called kitsch); which surely throws a slightly different light on the notion of the apparent autonomy of ‘art’s work’? Benjamin acknowledges that ‘[Greenberg’s] attack on kitsch and [his] need to maintain a site where art would be able to continue are themselves part of a general problem of determining how to respond to fascism’; yet, whilst situating Greenberg as a custodian of culture, he is less forthcoming on the cultural chauvinism implicit in the latter’s need to propagate the notion that the new American art was the pinnacle of advanced art, spurred on by a determination to rebrand Abstract Expressionism as ‘American-Type Painting’.

What Benjamin merely hints at- namely, Greenberg’s manoeuvrings and machinations in the wider world beyond the studio and the gallery- David Craven confronts head-on, in his essay ‘Abstract Expressionism and Third World Art: A Post-Colonial Approach to American Art’. According to Craven, Greenberg, along with Alfred Barr, Chief Curator of New York’s Museum of Modern art, must be seen as collaborators in a concerted attempt to depoliticise abstract art during the McCarthy era. The extent to which the avant-garde was under attack from the McCarthyite wing of the American political establishment at this time can be gauged from Congressman George A. Dondero’s infamous speech, ‘Modern Art Shackled to Communism’ which he delivered to the House of Representatives in 1949, from which Craven draws the following quotation: ‘I call the roll of infamy without claim that my list is all-inclusive: Dadism, Futurism, Constructivism, Suprematism, Cubism, Expressionism, Surrealism and Abstractionism. All of these ‘isms’ are of foreign origin, and truly should have no place in American art…. Add to this group of subversives the following satellites and the number swells to a rabble: Motherwell, Pollock, Baziotes, David Hare… [they are] the link between the Communist art of ‘isms’ and the so-called Modern Art of America.’9Congressman Dondero, G A, ‘Modern Art Shackled to Communism’ (1949), Congressional Record, First Session, 81st Congress, 16 August 1949

Greenberg and Barr, in Craven’s words, behaved every bit as passively as the Liberals in Congress who offered no opposition to Dondero, the pair of them ‘allow(ing) these hysterical attacks on the left to go unchallenged, and argu(ing) that avant-garde art was ‘apolitical’ and, as such, purportedly an expression of individual ‘freedom’ (contrary to everything we know about the European avant-garde’s call for both a radical trans-valuation of society and critique of the institutional affiliation of art). In this way, Barr delineated a major reason for the creation of formalist criticism, ‘cleansed’ as it was of political contumacy: it was a way of promoting Abstract Expressionism that denied both its insurgent cultural practices and its recalcitrant opposition to capitalism.’10Craven, D, ‘Abstract Expressionism and Third World Art: A Post Colonial Approach to American Art’ p36, included in ‘Discrepant Abstraction’ edited by Kobena Mercer, Institute of International Visual Arts, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England

For Craven, Greenberg was nothing less than ‘the formalist critic who interpretively purged abstract expressionism of its dissident politics’11ibid., p36; and if the substance of what he goes on to accuse him of doing might be believed, Greenberg was, in fact, a great deal more.12At the time of writing, it has not been possible to substantiate Craven’s allegation that Greenberg was an ‘active McCarthyist’. Although Craven does cite ‘Congressional Records 1951’ as a point of interaction between Dondero and Greenberg, he does not take a quote from them. Appendix I, below, refers to a book without giving page details; and also to an article which, whilst shedding light on the complex relations between American politics and advanced art of the time, does not refer explicitly to Dondero mentioning Greenberg in any context. However, it has been possible to chase down a passage in an essay that describes Dondero quoting, in Congress, a letter written by Greenberg accusing the editor of ‘The Nation’ of being a communist sympathiser (Appendix 2); this shows a closer alignment on Greenberg’s part with the McCarthyist ‘witch hunt’ mentality. Surely Greenberg would have calculated the potential impact of such an accusation at that time, and the interest it would have aroused in the McCarthyist Right?

Appendix 1: Craven backs up his assertion that Greenberg is an ‘active McCarthyist’ with the following footnote: Annette Cox, ‘Art-as-Politics: The Abstract Expressionist Avant-Garde and Society’, Anne Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982,151. Also see Jane De Hart Mathews, ‘Art and Politics in Cold War America’, The American Historical Review, 81, 4, October 1976, 762-78

Appendix 2: Full article here: http://shiftjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/battaglia.pdf

Whether or not one shares Craven’s view of Greenbergian aesthetics, and of the supposed ‘cleansing’ they helped bring about, and whether or not one gives credence to the substance of the shocking allegations that Craven goes on to level against Greenberg (as detailed in the footnote above) regarding the true nature of his political alignment, one must surely deal seriously with his observation that ‘post-1945 US art has not been predicated on the reductive process of ‘medium purification’ outlined by orthodox formalists like Greenberg, much less on escapist ‘apoliticism’ or ethnocentric values. Rather, post-1945 US art has emerged from an expansive and highly ‘impure’ process of cultural convergences in which Third World artistic practices – Native North American, Latin American, Afro-American and South Pacific in origin- have been enjoined with the European artistic traditions so ethnocentrically privileged by formalist apologists for US art.’13ibid., p33

Craven recognises that ruptures and crises have been the essential fuel for the engines of modernity; and he examines these events, considering as he does so the degree to which the will to create self-sufficient abstract images clashed headlong with the changing social, political and technological realities of post-war America. For him, ‘an artwork is not a unified whole, but rather an open-ended site of contestation wherein various cultural practices from different classes and ethnic groups are temporarily combined.’14ibid., p33

So, what kind of frictions are generated when we set Craven’s criteria for looking at abstract art against Benjamin’s? Benjamin asks for a more flexible ontology for contemporary abstract art, moving beyond Greenberg; but this ontology, I would argue, is not that flexible. He presents us with a series of tropes he has identified within contemporary abstraction: ‘affirmation of the worked surface’, ‘installed paintings’, ‘disrupted grids’, and (this one really gets the heart pounding) ‘placed paint’.

This sort of analysis has its place; but can it really provide the entire modus operandi for an artist’s practice? Benjamin’s range of reference seem limited, when compared with Craven’s recognition of the diverse influences at work within Abstract Expressionism, whether they be social, political or aesthetic.

Benjamin’s narrative, it seems, is set in a castle full of ancestral portraits and quiet libraries; whilst Craven’s social history of Abstract Expressionism evokes courtroom drama. Does the latter feel a little closer, perhaps, to our current relationship with abstract art and its fraught trysts with wider social contexts and history? Critic Barry Schwabsky has this to say about the contemporary artist’s dilemma: ‘The contemporary artist contends with two contradictory directives. For your work to be significant, and not merely art, don’t be formalist, let the world in! But for your work to be significant as art, it must investigate and criticise its own artistic presuppositions, thereby turning whatever comes within its purview into mere grist for art.’15Schwabsky, B, ‘The Observer Effect: On Contemporary Painting’, Sternberg Press 2019, p261

Schwabsky’s two, wonderfully pithy, ‘contradictory directives’ are, in effect, the horns of the dilemma that this essay is attempting to describe: which ‘reading’ of abstraction has the greater power to persuade, Craven’s or Benjamin’s? Craven’s Marxist retelling of much of the Greenberg story sends abstract art hurtling headlong into the anarchy of an uncertain present tense, trailing questions in its slipstream; does the abstract art being made now still carry some traces of resistance to capitalism, and of ‘the European avant-garde’s call for both a radical trans-valuation of society and critique of the institutional affiliation of art’ that Craven suggests were central to the development of Abstract Expressionism in the USA? Does abstraction still attempt to frustrate its own commodification by a demurral from the sorts of immediate digestible meanings that are tethered to representation? Or, conversely, do we view abstraction in Benjamin’s terms? Might this deliberate negation of representation on the part of abstraction be a move towards ‘another source of signification’ based on ‘art’s work’; a Greenbergian historical continuity maintained against all the odds by ‘freedom of mind’ and ‘the untrammelledness of the eye’, now more complex, more nuanced by our myriad subjectivities, those ‘irreducible determinations’ that come into play when we look at abstract art?

Benjamin’s reading is philosophically robust, for sure; but it is, arguably, an arid discourse, the internal monologue of an art form talking only to and about itself. And as Craven has shown, it’s a reading that overlooks Greenberg’s attempts to suppress other perspectives on the social and political tensions within Abstract Expressionism at a particular point in history.

So, where do I find myself now? As I look at works of art online, I am overwhelmed by a sense of the history of culture that is fractious, complex, full of competing, often contrary ideas about abstract art, its many incarnations, its past and present lives. The internet is too riven by alternative narratives (and sometimes ‘alternative facts’) to allow for any clear, linear, singular view of art history. Benjamin and Craven’s twin approaches are like theoretical tectonic plates grinding together, moving in response to the inherently unstable cultural geology of forces unique to our 21st century experience.

Maybe it’s time I got used to living here in these dark recesses where the tectonic plates grind? After all, this is where contemporary abstract art now seems to reside; in the fault lines between many cultures- places of instability and contingency- where past, present and potential futures push against each other in new and unsettling ways…

Jackson Pollock, ‘The Key’ (1946), oil on linen, 147.5 x 205cm

Edna Massey, ‘Untitled’ (c.1950), woodcut, 13 ×17.5cm

Lee Krasner, ‘Bald Eagle’ (1955), oil, paper and canvas collage on linen, 195.6 × 130.8cm

Norman Lewis, ‘Untitled (Alabama)’ (1967), oil on canvas, 114.9 x 186.7cm

Installation view of the exhibition ‘Indian Art of the United States’, January 22nd, 1941- April 27th, 1941. Photographic archive, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Fabian Marcaccio, ‘Paint-Zone # ll’ (1994-5), oil, collagraph on canvas, 162.5 x 152.5cm

9 thoughts on “John Bunker: ‘Irreducible Determinations; or, Following the Fault Lines’”

Comments are closed.

Greenbergian formalism is an explicating “master” discourse that became popular in art schools because it inherently reinforces privileged, hierarchical thinking.Marxism in this sense is no different from conservatism as they both share, in Adorno’s phrase, an intolerance of ambiguity. Unless you take account of the subject and of subjectivity you can never make precise or subtle enough formal decisions. The material cannot be privileged over the pictorial in painting because painting is, even in the case of Yves Klein, always in part a picture, subjectively constructed. Greenbergian formalism is so entrenched it’s been an uphill struggle to get beyond it but the innovators I’d point to in this regard are Merlin James, Peter Doig and Peter Ashton Jones, the creator of Turps Banana.

Hi there John

This may be a left field question….If it were it possible in a normal world ! …how would you like your own work to be discussed/debated and just simply talked about ?

I can’t resist food and gossip. It is quite clear Clem was elusive, vain, arrogant, dismissive, brilliant and human. American society was arguably much more interesting in the ’60s, when revolution was in the air, than now, when its so painful, obvious and missing nuance. Bob Dylan will be 80, his extremely dull art work is on sale in Exeter, without any anger or pain. It’s quite clear the Clem of ‘Art and Culture’ was brilliant, possibly fudging the categories of critic, philosopher, radical and historian. He could have been Noam Chomsky, with real bite, accepting duality, as Dan mentions. Unfortunately he fell for his own hype and began to believe he was useful in the studio.The temptation to believe he was all-seeing, all-sensing, an EYE, was too much. It was Noland’s listening to him, Olitski’s deference, his prescription for ‘Good Art’ that was catastrophic through the ’70s to ’90s. In about ’71, I was sitting with Larry Poons, Michael Steiner and Dan Christiansen in Max’s Kansas City when the short order chef came out in his white tall hat. He turned to the boys from Great Neck, and said, I’ll be up there above you all.It was Julian Schnabel, no painter (passable film maker). This was just to do with fame, the art had left a while before. There’s a nice picture of Clem and Helen, Lee and Jackson in Eddie Condon’s, when Clem had European Modernism behind him and it was classy. Without our struggle as Europeans, it was just banal opinion.

I find the piece difficult, probably because I find Greenberg and the like difficult. Maybe I am not interested in that depth of thinking about abstract art. You talk about abstract art, and the art Greenberg often refers to is abstraction. But I have to remember when his comments were made. At the time, all the post-war British Modernists were referred to as abstract artists; and their American counterparts. The majority was abstraction. Understanding has evolved. I like a distinction between abstract and abstraction, as I am not an abstract painter. More recently, purists suggest, referencing any environment weakens the abstract, therefore my paintings could never be abstract, though I accept others would only see them as abstract. If people ask, I explain my understanding of the difference. Can an abstract painting ever be achieved from referencing an environment? For me, purely abstract can be too scientific (technical, systematic, logical, controlled) in concept and practice. For those artists, there is nothing wrong with such an approach; I simply want to engage in a different way. From the images used, the Barnett Newman and Kenneth Noland I regard as abstract, in being unaware of any reference. Caro’s ‘The Window’ is far less abstract, especially when linked to a referential title. Following on from Dan’s comments, Merlin James, Peter Doig and Peter Ashton Jones are painters using abstraction, while offering individual and at times new ways of responding to a subject. During lockdown, I too have been looking deeply into why, what and how I paint, reaching conclusions and ways forward. There is no desire to climb down into the ‘dark recesses where the tectonic plates grind’. I studied ‘A’-level Geology, so have tectonic plates covered. Such questioning tends to come from true abstract artists. These days, because of Greenberg, any representational painting that moves slightly away from representation is regarded as abstract; galleries are full of artists claiming to paint abstract landscapes. Is this insecurity on the part of abstract artists, in not having a specific place to call home? From the time of Greenberg, abstract artists have been living in the same home as abstraction. Should purely abstract artists have their own household?

Dear Keith, I don’t want to spend all day writing, as there is painting to be done. However, my point is, it’s not to do with appearance. Greenberg and Motherwell got off on the Surrealists, etc., and the Congressman’s list of subversives was spot on. However, once the revolution that occurred at the Bauhaus and elsewhere faded in New York, once Modernism died, the art failed. We have got to rekindle that spirit of total reinvention and rediscovery that produced Pollock, Miles Davis, Arshile Gorky.

‘So Greenberg was one of the first to see the incomparable greatness of Matisse, at a time when Picasso still occupied the center ring of the circus. But if Greenberg’s insight was that the decorative residue of painting might be the best thing about it, his evil genius was to enforce this insight with a coercive historical scheme, and then police it with totalitarian arguments. The scheme, borrowed from Marxist dialectics, was that History allowed no other alternative to abstract painting— the flatter and the more openly abstract, the better. The policing took place through Greenberg’s insistence on his own eye as the only arbiter of the dialectic.’ Adam Gopnik

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/04/12/helen-frankenthaler-and-the-messy-art-of-life?utm_campaign=falcon&utm_source=facebook&utm_brand=tny&utm_medium=social&utm_social-type=owned&mbid=social_facebook&fbclid=IwAR3V76-gMxTwidTWVdRXg5cDQgw7M5yRpp0KMJDr2jKol8YxiGASqXdeGKk

I’m amazed that people are still making the gross assumption that Clement Greenberg is the fount and origin of wisdom about Modernism in painting, as if nothing happened between the advocacy of Apollinaire, the dialogue between Schoenberg and Kandinsky, the Bauhaus, De Stijl, the International Style as propounded by Philip Johnson and co, etc.,etc. (on which Greenberg relies heavily). Not to mention Roger Fry and Hans Hofmann.

Greenberg’s diffidence in acknowledging his own part in the far-leftist politics of the 1940s was shared by many artists, poets and musicians during the McCarthyite purges, because they didn’t want to go to jail. Richard Taruskin covers all this brilliantly, as regards, on the one hand, Aaron Copland ‘s testimony before the Unamerican Activities hearings, and on the other the total serialism, ie. total abstraction of Milton Babbitt’s music . I urge a reading of his ‘Oxford History of Western Music’ -The late 20th Century.

So that Greenberg’s remark that ‘one day it will have to be explained how anti-Stalinism became art for art’s sake’ covers a multitude of sins.

What remains to be explained is what effect, if any, all this politics had on the appearance of the paintings. Motherwell titles his painting ‘Elegy for the Spanish Republic’, thus accruing extra-pictorial resonance, or extraversive signing, in the jargon.

But how do we know that the ‘content’ of the painting carries a political charge, if, in Motherwell’s own definition, ‘the content of painting is our response to the painting’s qualitative character, as made apprehendable by its form’?

Wonderful to have Alan’s insight into Modernism. Motherwell’s title ‘Elegy to the Spanish Republic’ is a perfect little poem, by the most literary of painters, to confer gravity and grandeur on his own efforts. When you look at what Miro and Tapies had to go thru in Franco’s Spain, it was less glamourous.They certainly risked deportation, if not death. There was always something very romantic, even in Hemingway, about the Americans’ political allegiances to righteous causes(witness Bogart’s character in ‘Key Largo’).Ken Loach deals with the complexities and ambiguities in his films, ‘Land and Freedom’ and ‘The Wind that Stirs the Barley’, as does Neil Simon in the Michael Collins epic.

I feel Modernism cannot displace socialist thinking, as every decent artist wants a civilised society to move toward freedom and equality, away from Fascism, as a given aim. The failure of this ambition would mean the failure of Modernism, which would be, in effect, John Bunker’s cracks in the facade. This has produced a terrible, bankrupt Art World system of galleries/collectors/prices, and crass Conceptual Art. We can no longer support the old political systems, such as Liberal Capitalism, because of real emergencies for the world’s future, which our children will have to deal with, like climate change, and the corruption at the heart of Popularism.

‘…to allow for any clear, linear, singular view of art history…after all, this is where contemporary abstract art now seems to reside; in the fault lines between many cultures- places of instability and contingency- where past, present and potential futures push against each other in new and unsettling ways.’

Much food for thought; and wholeheartedly agree, John! The only place to reside, always, is on or between the fault lines. This is in order to have any possibility to be free of the tyranny and inevitably exposed flaws of ‘clear, linear, singular views’ of anything.