Charley Peters: ‘Crazy Like Machines: Cyborg Abstractions in the Technological Age’

In her third piece as an Instantloveland writer-in-residence, Charley Peters examines how Eva Hesse’s ‘real nonsense’ has opened pathways for painters working now…

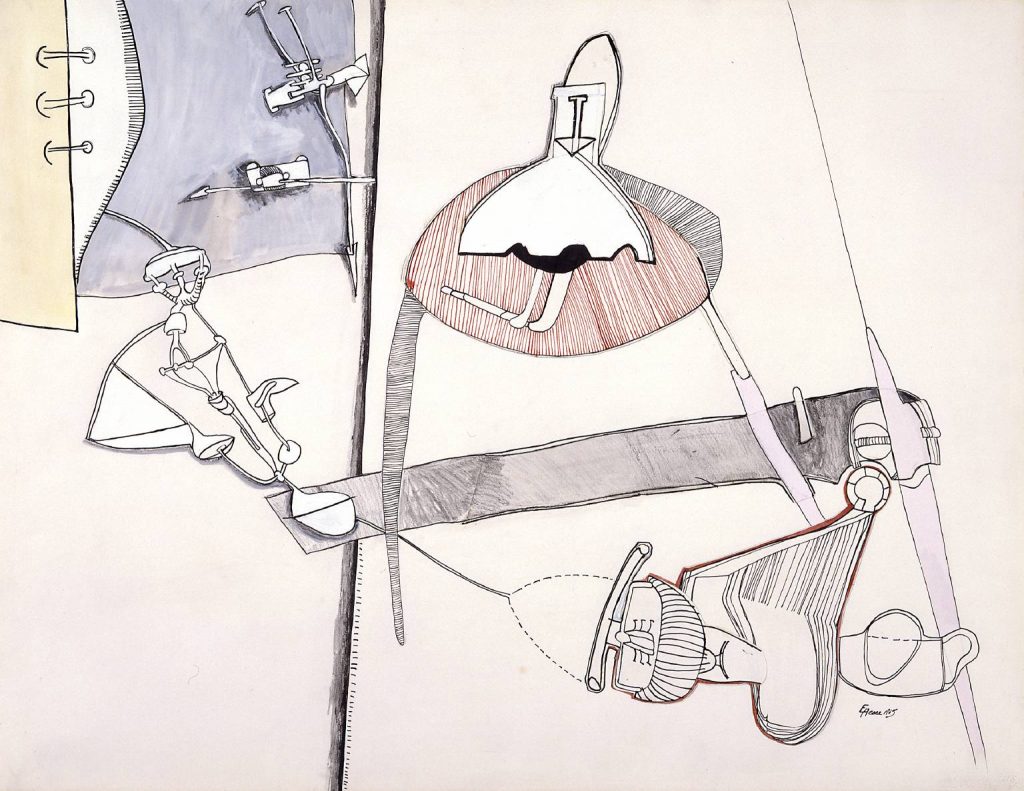

During 1964-1965 Eva Hesse was based in Germany, working in a studio space above an abandoned factory as the guest of a textile manufacturer and art collector. In her time in the studio, which was strewn with relics of machinery and offcuts of cord, she began to draw the objects that surrounded her. Through her drawings, these redundant machine parts were transformed from industrial objects into disjointed, quasi-bodily shapes. She drew diagrammatic outlines of suction tubes, swollen sacs and strangely articulated appliances, reminiscent of the body’s interior architecture, in black and coloured inks on paper. The untitled drawings described disparate suggestions of pipes, pouches, cables and rivets, in configurations held together by sparsely but gracefully rendered lines that defied gravitational truth and suggested broken, engorged or dangling anatomy. At the same time abject and whimsical, their narrative remained elusive, like blueprints for disjointed cyborg creations, neither describing actual bodies or functional mechanics.

Uncertain about the new drawings, Hesse described them in a letter of March 1965 to her friend, the artist Sol LeWitt, as, ‘Drawing – clean – clear – but crazy like machines, forms larger and bolder, articulately described. So it is weird. They become real nonsense.’ His response, in what has become a much referenced letter of advice on self-doubt and overcoming creative block for artists, was ‘That sounds fine, wonderful — real nonsense. Do more. More nonsensical, more crazy, more machines, more breasts, penises, cunts, whatever — make them abound with nonsense’.1Pdf of the handwritten letter: http://magazine.art21.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/sol-eva-letter.pdf Transcription of the letter: https://borisinjac.com/sol-lewitts-letter-eva-hesse

Hesse did make more, and soon these drawings would inspire her reliefs, in which she unified biomorphic and mechanical forms in three dimensions. The conjoining of oppositional qualities became characteristic of Hesse’s work, in which she explored through formal, material and aesthetic means, concerns such as line and volume, hardness and softness, the synthetic and organic, abstraction and figuration, all of which were first exemplified in her mechanical drawings.

While Hesse was in Germany, she was reading Simone de Beauvoir’s ‘The Second Sex‘2Beauvoir, S. D., ‘The Second Sex’ (1989). New York, Vintage Books. (18th ed.) , a major work of feminist philosophy in which de Beauvoir asks ‘What is woman?’ and argues that man is considered the default, while woman is considered the ‘Other’, defined not in absolute terms, but as relative to man. In her journals from this time Hesse wrote descriptions of the mechanical drawings alongside quotes from De Beauvoir’s feminist existentialism, one of which was: ‘Transcendence to arise above beyond into another space.’ De Beauvoir used the concept of ‘transcendence’, and its opposite, ‘immanence’ to describe the social situation of women. Immanence is a term that De Beauvoir used in regards to an oppressive set of historical beliefs under which women were raised until they were no longer aware that they had autonomy of thought. Immanence rendered women as passive, interior and static. In ‘The Second Sex’ immanence is understood to have related to ‘body’, and ‘transcendence’ to ‘consciousness’. Transcendence, for De Beauvoir, denoted activity, productivity and moving forward into the external universe, and in particular, to a state of being in which women could escape from imprisonment by socially constructed modes of behaviour and achieve future freedom. De Beauvoir’s concepts of transcendence resonated with Hesse as thoughts that she could embody though her work. Hesse’s journal notes consider transcendence as a state of being that was able to articulate ‘another space’, an experience beyond self-conscious binary gender difference and absolute definitions of being. Her notes from that time continued to relate her mechanical drawings to De Beauvoir’s notion of freedom through transcendence, in another entry she wrote, ‘…if crazy forms, do them outright. Strong, clear. No more haze’3Hesse, E., Rosen, B., & Bloomberg T. (2016), ‘Diaries: 1955-1970’, Yale University Press, p409, and then, ‘Simone DB writes woman is object—has been made to feel this from first experiences of awareness. She has always been made for this role. It must be a conscious determined act to change this.4ibid., p411‘ From the point at which she began to relate the mechanical drawings to concepts around progressive social orders, Hesse continued to make work that rose above definitive truths, where antithetical terms such as male/female and human/machine were fused in, to quote Lewitt, her own ‘world’, which was simultaneously synthetic, bodily, erotic and absurd.

Today, both Hesse’s abstractions and the idea of eroding binary oppositions seem much less absurd. We are living in an unprecedented time where gender identity is autonomous and fluid, and humans have never been so physically connected to technology. The virtual space of the digital screen is the prevailing means by which we view and understand our experiences, the machine world is now intrinsically tethered to our own as our contemporary bodies exist in a (virtual) environment in which traditional understandings of physical and spatial contexts have been remodelled. Our experience of the corporeal self as an entity separate from technology no longer exists, as the majority of us are, in the Western world at least, connected to the internet, reliant on virtual modes of communication and under surveillance every day. Our smartphones are literal extensions of our bodies, and physical touch and gesture are now synonymous with the digital, the Latin root word ‘digitus’ meaning ‘finger’ or ‘toe’. We are living in a commixture of the tangible and intangible – not an oppositional space, but a new space, suggestive in some way of the transcendence invoked by Hesse’s mechanical drawings.

Approaching transcendence by erasing learned, constructed codes of behaviour, and dissolving oppositional terms relating to gender, organism, machine, self, other, etc., can be seen as a means by which to address the problematics of Western traditions such as patriarchy, colonialism and essentialism, which have historically defined things as ‘other’ and established a hierarchy of power. In ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’5Haraway, D., ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century’, 1991, in: Haraway, D., ed., Simians, Cyborgs, and Women, 1st ed. New York: Routledge, pp.149-181, Donna Haraway described the concept of the cyborg – a term she uses strictly metaphorically – as a rejection of rigid boundaries, notably those separating ‘human’ from ‘machine’, ‘man’ from ‘woman’, ‘physical’ from ‘non-physical’, ‘self’ from ‘other’. She defines these oppositional differences as ‘antagonistic dualisms’ [that] ‘have all been systematic to the logics and practices of domination of women, people of colour, nature, workers, animals… all [those] constituted as others’ and writes of a need to develop a world beyond these dualisms.

In the 50 years since Hesse made her mechanical drawings our relationship with technology has changed significantly, and we can also clearly see its influence on abstract painting, in the ways in which artists negotiate pictorial space, apply ‘backlit’ colour, and use the now familiar language of the screen within practices of painting. Can we also still locate the transcendent space that de Beauvoir wrote about, and/or the cyborg of Haraway’s essay, within contemporary abstraction of the screen age as the physical and virtual worlds have moved closer together? Two contemporary artists whose work engages with dialogues across the boundaries of object/human, female/male and abstraction/figuration are painters Loie Hollowell and Anna Nero, whose works are characterised by the use of refined techniques to render painted spaces inhabited by strong shapes and rich colour that are bodily, fetishistic and positioned within the familiar visual language of the digital.

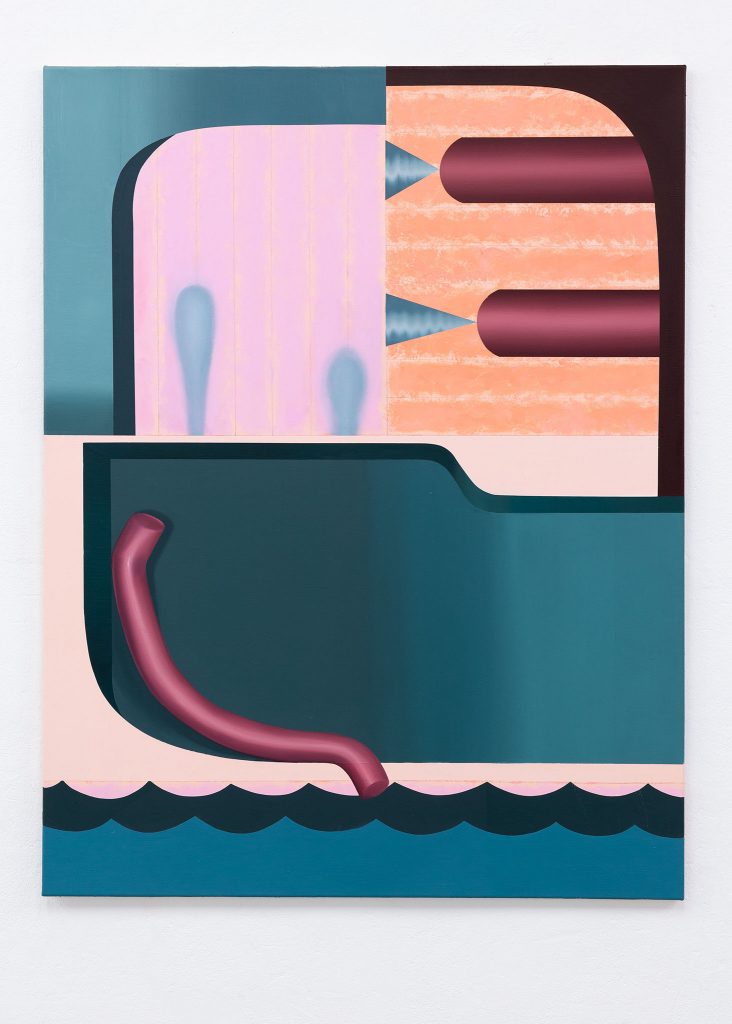

It would be difficult for painters today to not habitually look, think and work in ways that are influenced by our experiences of technology. The layered logic of digital imaging software such as Adobe Photoshop has affected our expectations of colour, pictorial depth and volume, and the capacity for us to see several windows on our computer screens at once has normalised fragmented, illusionary spatial composition. The digital environment has impacted on our understanding of the conventions of painting and in turn, this has influenced the formal considerations that lead to an artist’s application of paint in terms of the physical sensations and haptic qualities of the surface as a contrast to the dematerialised space of the screen. Anna Nero employs multiple methods of painting within each canvas; her works are suggestive of implied three-dimensional objects and physical spaces but any holistic pictorial logic is interrupted by intuitive brush strokes and spontaneously applied daubs or sprays of paint. She brings together strictly constructed internal architectures, often based around grids or hard-edged geometric shapes, with freely applied painted marks. Although gestural, these painted elements appear formal, add texture and compositional value to each work, and are in contrast to her carefully rendered areas of painting, which are reminiscent of digitally generated vector graphics.

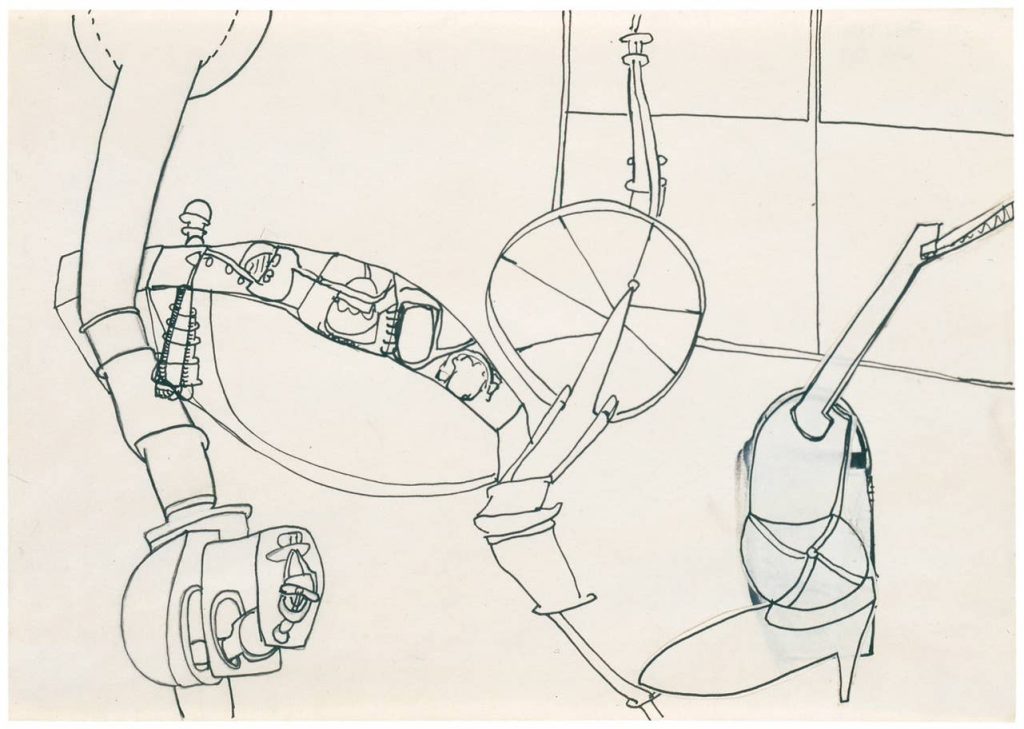

Like Hesse’s mechanical drawings, Nero’s works feature painted shapes that suggest pipes, wires, and bits of hardware. Bent, limp tubes expel liquids or clouds of gas, and wet patches lie on illusionary three-dimensional surfaces. Although the objects in them are placed next to each other in an often playful and flirtatious manner, there is something vaguely sinister about her imagined landscapes. Nero is fascinated by the life of objects, especially mass-produced ones, and by our relationships with them. She does not describe specific, recognisable objects, but they often feel familiar – uncomfortably corporate or strangely erotic, yet always devoid of function, and seen in relation to other, similarly decontextualised things. Nero talks about raising objects to a higher status: ‘The idea that’s probably most appealing to me in all its spectrum is the idea of fetishism. Whether in terms of religion or sexuality, I like to think about different possibilities of relationships between people and objects. What do people read into things? They can love them, worship them, assign powers to them, be scared of them. I always thought that this basic but somewhat irrational relationship of some people to certain objects is the origin of art as we know it today.’6 https://yngspc.com/artists/2018/09/anna-nero/ In her work, objects, and painted gesture-as-object, become players or characters within the paintings. They are personified through their posture, weight and relationships to other pictorial elements, becoming a hybrid human-object and thereby achieving agency.

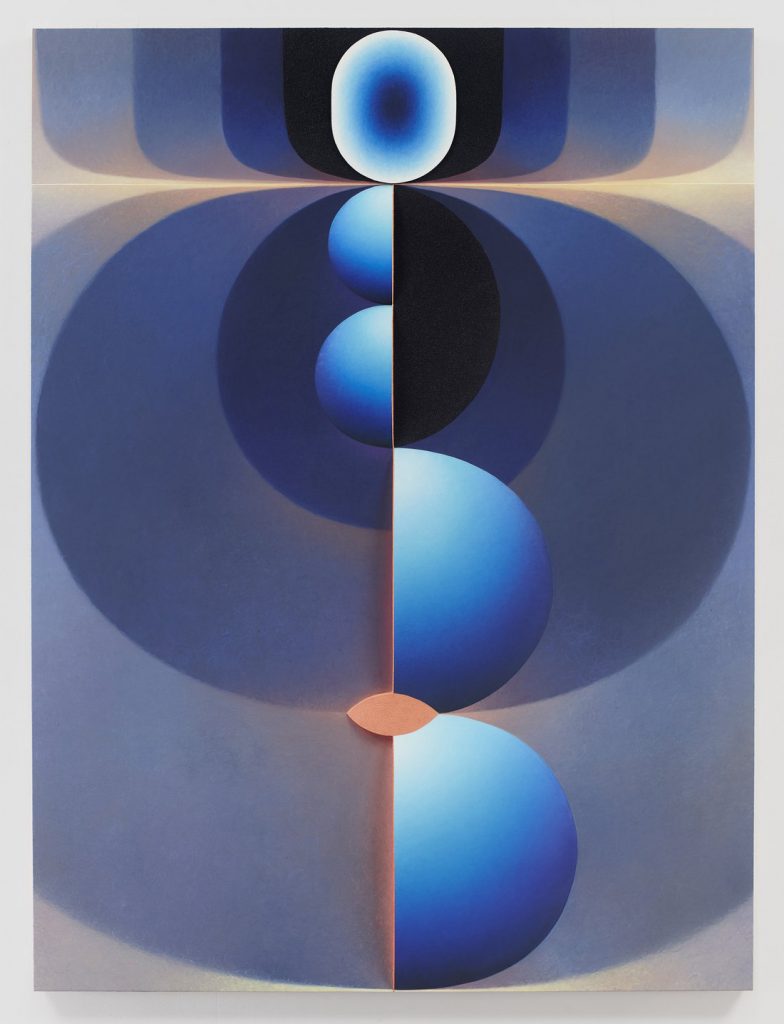

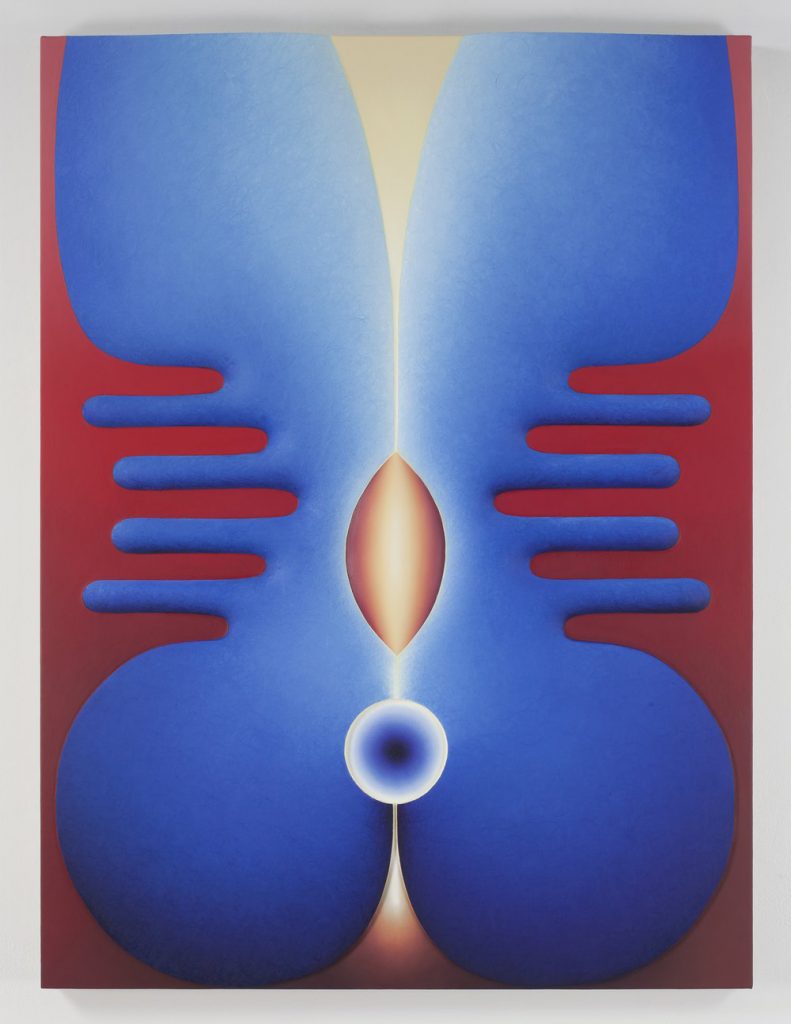

In the work of painter Loie Hollowell, the human-objects she creates are powerful, erotic images that exist, deceptively, not as flat, painted surfaces but as constructed three-dimensional reliefs. Minimal geometric shapes, often composed symmetrically, are built up in layers of high-density foam, its bulging contours meticulously painted in high-contrast colour to further accentuate the curvature of the work’s surface. In the flesh, Hollowell’s works have an unexpectedly rough grain, the result of their being covered with textured brush marks or paint stippled on with a sponge. Hollowell’s blended fields of colour are suggestive of the screen gradients synonymous with digital colour palettes; and also redolent of retro sci-fi graphics from an era before the accelerated development of technology. She carefully mixes colour and tone to heighten the physicality of the work – describing shadows and light as they fall on a three-dimensional surface. Yet when seen on screen, her technique has the almost paradoxical effect of flattening the work, rendering it image-heavy and devoid of physical surface, which is, of course, how we now digest most material artworks in our screen-based culture.

Hollowell is clear in her references to the sexual body on her canvasses, where male and female parts join or exist as part of a cohesive, universal form. Yet there is also something uncanny about their appearance, the glowing orbs that suggest buttocks are constructed as if they are diagrammatic cross-sections of planets, and penises look like monoliths or rockets, lit as if metallic and futuristic. The reduction of anatomy to geometric shape and strong colour denies us the information necessary to relate to them in wholly human terms. The body, or the interaction of more than one body, is implied through a shorthand of symbols, connected to other shapes with no allusion to gravity or perspective. Seemingly viewed from above or as slices of an implied whole, in some ways Hollowell’s body-objects are as diagrammatic as Hesse’s drawings, albeit more ‘fleshed out’ in material terms.

Hesse’s mechanical drawings were made in a time before we lived with the everyday reality of technology as a literal extension of ourselves. They were absurd nonsense that boldly combined organic and machine parts into a new, transcendent space. In her journal at the time of making the drawings she wrote, ‘What woman essentially lacks today for doing great things is forgetfulness of herself; but to forget oneself it is first of all necessary to be assured that now and for the future one has found oneself.’ She had found a new reality of transcendence that allowed her to position herself in ‘another space’ in her art, which considered oppositional definitions of being – male or female, human or machine – as abstract experiences in themselves, and not absolutes. The digital age has further enabled us to consider these alternative spaces, by the development of a screen-based visual language that defies definition as either strictly embodied, or disembodied; a cyborg abstraction.

Eva Hesse, ‘Untitled’, (1965), ink on paper, 45.7cm × 61cm

Anna Nero, ‘Lightning’ (2017), oil and acrylic on canvas, 40cm x 30cm

Loie Hollowell, ‘Lingam Twist in Red and Green’ (2016), oil and acrylic medium on linen over panel, 71.1cm × 53.3cm × 5.7cm

Loie Hollowell, ‘Direct Shot’ (2018), oil paint, acrylic medium, sawdust and high-density foam on linen mounted on panel, 121.9cm × 91.4cm × 8.3cm

Anna Nero, ‘Intimacy’ (2019), oil and acrylic on canvas, 120cm x 160cm

2 thoughts on “Charley Peters: ‘Crazy Like Machines: Cyborg Abstractions in the Technological Age’”

Comments are closed.

This is brilliant Charley! Really interesting. It makes me think one role of painting relative to the digital (and screen based imagery) is to slow our relationship to the digital down so that we can begin to see it at a pace that is more in tune with the restrictions of still having to live in our physical bodies. Painting in this sense gives us chance to catch up with our posthuman, digital identities that exist beyond the screen. Maybe this is particularly pertinent in these Covid times where we have been forced to chill out? Painting, as it inhabits the language of the screen, forces us to think of the materiality of the digital, and breaks the illusion of the screen being immaterial. Maybe this functions in a similar way, and can also help us to better understand our digital otherness?

Great article Charley. The link with Simone de Beauvoir is spot on and makes for a compelling read. I often drool over my book of Eva Hesse drawings and this piece really helps to link them to now. It also has me thinking about Judy Chicago’s stunning car bonnet paintings as perhaps some sort of segue to the digital pinpoint accuracy of Loie and Anna’s exceptional works.