Matt Dennis on Patrick Heron: Signs for Seeing, Signs for Things Seen

Someone really ought to have had a word with the curators of Tate’s Patrick Heron show, which finished the second part of its run at Turner Contemporary in the first week of January. I’m referring, of course, to the decision that prompted so many strong reactions, both positive and negative: hanging the show by thematic headings (‘Edges’, ‘Unity of the Work’, ‘Asymmetry and Recomplication’, ‘Explicit Scale’) rather than going down the obvious route of starting- more or less- at the beginning of Heron’s oeuvre and finishing at the end. I visited the show twice: once in St Ives, and once in Margate; and although the transfer from the former to the latter had resolved some of the problems that had beset it in its first staging- the level of illumination in the galleries at Turner Contemporary was far brighter than the inexplicably dim greyness of the lighting in the newly-opened extension in St Ives; and unlike St Ives, they hadn’t sacrificed an entire large room to a dedicated Patrick Heron gift shop annexe, preferring to use the space not given over to the paintings to host a number of his gouaches- but there on the walls at Margate were the same four pieces of didactic signage that had hung so unhelpfully at St Ives, struggling to be heeded amid the clamour of Heron’s colour in a way that seemed unintentionally comic, like a beleaguered parent gamely trying to explain the rules of ‘pass-the-parcel’ to a roomful of hyperactive eight-year-olds. The paintings showed no inclination to fall in line with these written instructions; and there was no good reason for the viewer to do so either. Dividing up Heron’s art by categories, and hanging it accordingly, with no regard for chronology, does him a tremendous disservice: it creates an impression of him as a kind of variety artist, able and willing to switch between styles and manners at will, rather than the kind of artist he really was, for whom ‘each painting spawn[ed] its successor’1Heron, P., ‘My Painting Now: 30th August 1987’, p19, in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988; in other words, an artist whose progression was always linear, the lessons learned in the resolution of each work feeding into the conception of the next in what he himself called ‘perpetual mutation…sometimes proceeding at a snail’s pace, at other times with terrifying abruptness’2Ibid.. The best way- arguably, the only way- to get the measure of Heron’s career, with its sudden doublings-back to revisit abandoned modes of working, and its long periods of close attention to a particular set of formal concerns that suddenly give way to seemingly radically different preoccupations, is to be allowed to see it, to feel it unfold chronologically. Were the curators simply shy of doing the obvious thing? The obviousness of a choice doesn’t in itself render it the wrong one. Rachel Cooke, writing in the Guardian, was surely right to conclude that the curation was ‘a jumble; its focus obscure, its motivation patronising.’3Cooke, R., ‘Brilliant, Colourful, and Completely Out of Order’, 20th May 2018, http://www.theguardian.com

Still…two can play at that game. What follows has no pretensions towards being any kind of comprehensive, definitive account of Heron’s painting: but is an attempt to record, under four headings (an only slightly ironic dig at the show’s curation) a series of impressions gathered by doing what the hang was so keen to discourage- that is, following as much as possible his timeline; and in the process, coming to understand a little better how complicated, contrarian, and occasionally radical an artist he turns out to have been.

Something had to give…

‘Christmas Eve’ of 1951, the largest of the handful of representational works on show, is crammed from edge to edge with bunched, looping, zigzagging, stuttering, cursive charcoal line, infilled with crazed patterning of coloured shards and stripes; decorum is maintained, but only just: the colour demands to breathe, to expand, whilst the line hems it in everywhere, enforcing an inch-wide no-go zone of bare grey priming along the entire length of its route. It is the masterpiece of Heron’s mature figurative style; but as is so often the way with masterpieces, it seems to usher in a terminal phase for the very method of working that made its creation possible in the first place. A kind of critical mass of surface activity has been reached. It is very hard to look at this painting and not think: something had to give.

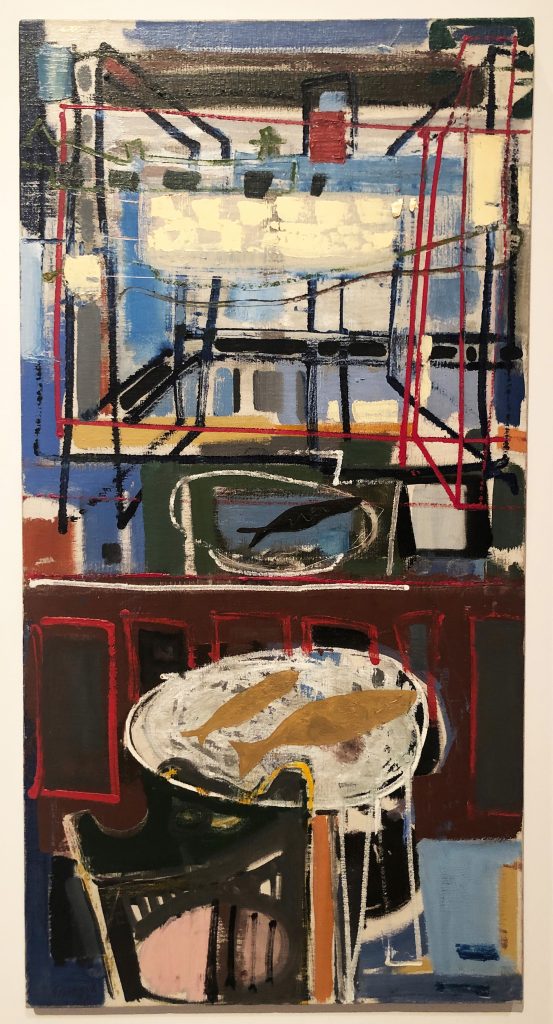

What did give, of course, was figuration. Unsurprising, really: Heron’s figurative works entirely lack the feeling that is always inescapably there with Picasso- that the distortions, stylisations and simplifications are intended to bring us back to the subject with renewed force. Figuration, for Heron, was the point of departure, not return: he was, in a sense, always an abstractionist-in-waiting. ‘St Ives Window with Sand Bar: 1952’ seems, in its very structure, to capture him in the act of not merely travelling away from figuration, but divesting himself of it: the bottom half of the painting sports three perfunctory silhouetted fish on plates- a tired visual trope, even for then; a half-hearted quoting from his beloved Braque that functions as nothing more than a kind of stamp, certifying the painting as ‘still-life of European modernist lineage’. But then the eye rises into the top half, and finds a complex, shifting play of line and plane that pits a perspectival cage drawn with the nozzle of the tube against declarative swatches of brushed colour; in effect, an inventory of all that Heron would go on to concern himself with once he renounced depiction in favour of an exploration of the ‘superbly exciting facts’ 4Heron, P., ‘A Note on my Painting: 1962’, Catalogue of Galerie Charles Lienhard exhibition, Zurich, 1963, reprinted in Art international, 25th Feb 1963; reprinted in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988, p34of spatial colour.

Not the heat of the ‘I’, but the cool of the eye

Heron’s move into abstraction coincided with the ‘moment’ of its upsurge into the wider postwar culture; and it is tempting, therefore, to try to situate him in close relation to the American abstract painters who had so fired his imagination in the Tate’s near-mythical ‘Modern Art in the United States’ of 1956. And yet, judging by the paintings at Turner Contemporary, it is clear that it wasn’t just the Atlantic Ocean that divided Heron from his Abstract Expressionist peers. He and they had renunciation in common, certainly: Heron recognised in their painting a shared striving towards ‘total freedom not only from figuration, but even from that abstraction which somehow still evoked familiar visual facts, whether of still life or landscape’;5 Heron, P., from ‘Five Americans at the Institute of Contemporary Arts’, ‘Arts’ (New York), May 1958, reprinted in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988, p32 echoing Newman’s famous observation that abstraction had liberated art from ‘the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, legend, myth, or what have you, that have been the devices of Western European painting’.6Newman, B., ‘The Sublime is Now’, Tiger’s Eye Vol 1, No. 6, December 1948, pp51-53, reprinted in ‘Art in Theory 1900-2000’, Ed. Harrison, C., and Wood, P., Blackwell Publishing, pp580-582 They were all moving away from the same things; but the destinations they were headed towards were very far apart: Heron’s ‘Scarlet Verticals: 1957’ is as spare and entirely abstract as anything of Rothko’s, but feels completely free of the latter’s glowering intensity. Its stripes and swatches of thinned colour are relational in a breezy, insouciant way the American painters never managed: for the simple reason that breezy insouciance was never an option for them, preoccupied as they were with making every canvas an avatar for the uniquely suffering self, refining their forms down to heraldic, autographic emblems- Newman’s ‘zips’, Gottlieb’s discs and erupting black stars. Heron may well have described ‘the artist who never feels, as he starts a new picture, that this time he is tempting madness to envelop him’ as ‘no artist at all’;7Heron, P., ‘The Changing Forms of Art’, 1955, pp3-20, reprinted in ‘Recent Paintings’, Gouk, A., in ‘Patrick Heron’ Barbican Art Gallery, 1985, p19 but he understood this struggle as essentially formal, rather than psychological: the drama of painting, rather than the painting of drama. Heron’s abstraction, as much as it looked backwards to a set of continental influences, was always outward-looking: the brushed lozenges, circles, fields of colour of his works of the late 1950s and early 1960s do not reference the physical world directly, but establish sets of relations that feel analogous to those discovered by looking at it. Pollock’s ‘I am nature’, in its implied solipsism and self-absorption, was anathema to him: nature was nature, and his task was to find, through paint, a visual experience which, whilst self-referential, might match it in richness. ‘The nature of his language [was] determined not in the heat of the “I” but in the cool of the eye.’8Power, K., ‘Looking at Lasker: The Surprise of Syntax’, in ‘Jonathan Lasker: Paintings, Drawings, Studies, 1977-2003, Museo Nacional, Centre de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, 2003, p35

‘Hand-stroked, hand-scribbled, hand-scrubbed’

What is it, then, that can help make the claim that Heron’s art could be radical? Definitely not his choice of antecedents: the four saints at the corners of his bed were Bonnard, Matisse, Picasso and Braque, ‘the French masters [he] so admired’ and there is a great deal in Heron’s painting- the drawing with the brush, the flickering fields of paint-strokes- that can be seen as the adoption of their figurative means as abstract ends. The answer, paradoxically, lies in the thinking behind the apparent narrowness of Heron’s approach to the paintings’ making. Nowhere in any of the paintings hanging in Margate is there any evidence of spraying, spattering, squirting, soaking, or staining: any way at all, in fact, of getting the paint onto the painting, and manipulating it once there, that didn’t involve direct physical contact between canvas and hand-held implement- specifically, the brush (bristles and handle) or the nozzle of the paint tube. ‘Hand-stroked, hand-scribbled, hand-scrubbed’:9Heron, P., from ‘Two Cultures’, Studio International, December 1970, reprinted in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988, p35 this was Heron’s mantra, the outward expression of his deeply-held conviction that ‘surfaces worked in this way can- in fact they must- register a different nuance of spatial evocation and movement in every single square millimetre’.10Ibid. For Heron, this hand-worked quality was the single indispensable constant, the one guarantee of authenticity, that his painting had to have: and if it were present, then he felt empowered, as it were, to play fast and loose with any and all of the other givens of modernist abstraction: to test them, to push against their limits. And push he certainly did…

Patrick Heron, ‘Complex Greens, Reds and Orange: July 1976- January 1977’, oil on canvas, 101.6 x 152.4cm

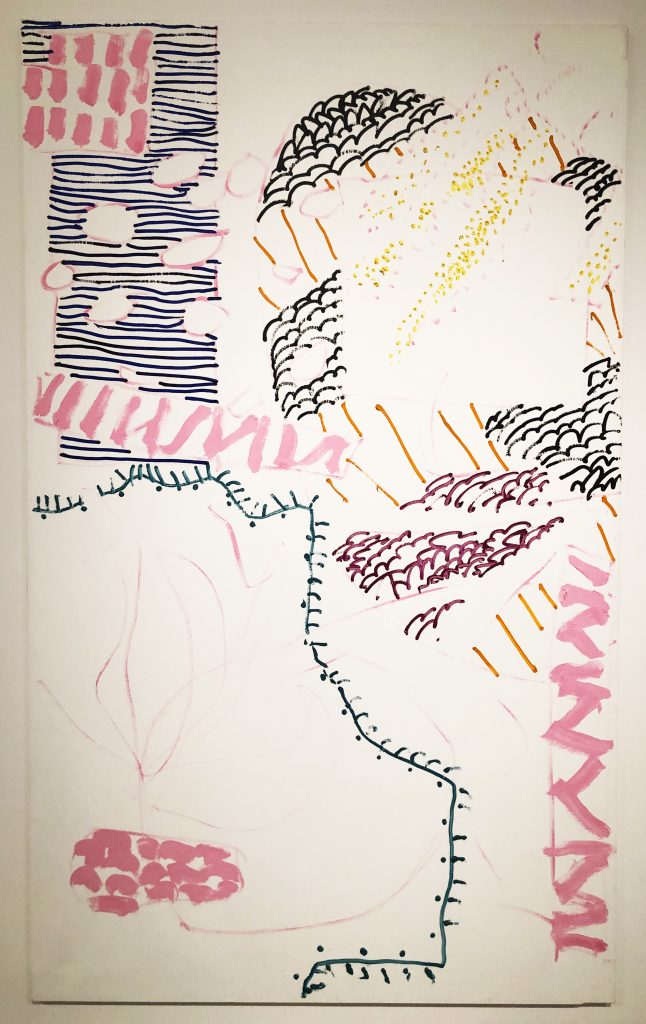

Time and familiarity have blunted the impact of the ‘wobbly hard-edged’ paintings somewhat; but to encounter ‘Big Complex Diagonal with Emerald and Reds: March 1972- September 1974’ again was to be reminded of its sheer weirdness, and the weirdness of the other works from the decade, give or take, that Heron devoted to this kind of painting. The facts of their facture read like the painter’s life re-imagined as absurdist drama, something out of Samuel Beckett: 13-hour stints at the canvas without a break, laying in (with what Alan Gouk has described, using brilliant understatement, as ‘somewhat uncharacteristic meticulousness’11‘Recent Paintings’, Gouk, A., in ‘Patrick Heron’ Barbican Art Gallery, 1985, p21 ) vast square-footages of pure, unmixed colour with small Chinese brushes, right up to the lines of his preparatory drawing, which had been laid down in a matter of seconds, and which, once executed, remained fixed and unalterable. Writing in 1958, Heron had decried ‘mere quickness in actual execution’12Heron, P., from ‘Five Americans at the Institute of Contemporary Arts’, ‘Arts’ (New York), May 1958, reprinted in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988, p33 as ‘a false criterion of excellence’ 13Ibidand demanded ‘a new and fine deliberateness’;14Ibid but what his ‘deliberateness’ delivers in paintings such as ‘Complex Greens, Reds and Orange: July 1976- January 1977’ feels more like a deconstruction of Modernist abstraction that anticipates by the best part of a decade the procedures of a Postmodern artist such as Jonathan Lasker, who famously separates out the key trope of a Modernist painting- the spontaneous, freely generated autographic mark- from the other elements of its facture by first laying down his entire composition as a rapidly-executed, small-scale sketch in Biro and felt marker, which then serves as a maquette to be painstakingly copied, freehand, at vastly enlarged scale, to produce the finished work; thereby redefining the forms of Modernism’s heroic individualism as a set of frozen signifiers. In Heron’s case, the free automatism that should have attended the entire painting process of his ‘Complex Greens…’ from start to finish -had he been playing according to Modernism’s rules- has instead been expended in the first few seconds, as the canvas was divided by the rapid strokes of his nylon-tipped pen; that done, the colour has then been exhaustively applied over the entire canvas surface, turning the lines of drawing into frontiers between hues, and the painting as a whole into an immaculate body, sealed off from the viewer by its perfect, unbroken skin. Its very perfection of finish has something defensive about it: as if to push a painting so remorselessly in the direction of an exploration of colour and contour, to the exclusion of all else, was so heretical an act that Heron had to hide behind a barrier of flawless technique. He was not a proto-Postmodernist: to repeat, his concern was always with the celebration of visual sensation and the means of its transmission, rather than a critique of the viability of those means, or of visuality as the assumed goal of painting; but in his preparedness to isolate and massively heighten one aspect of Modernist practice, whilst reducing others to invisibilty, he presaged, by default, the interrogation of painting that was to become the driving force in the work of the generation that followed him.

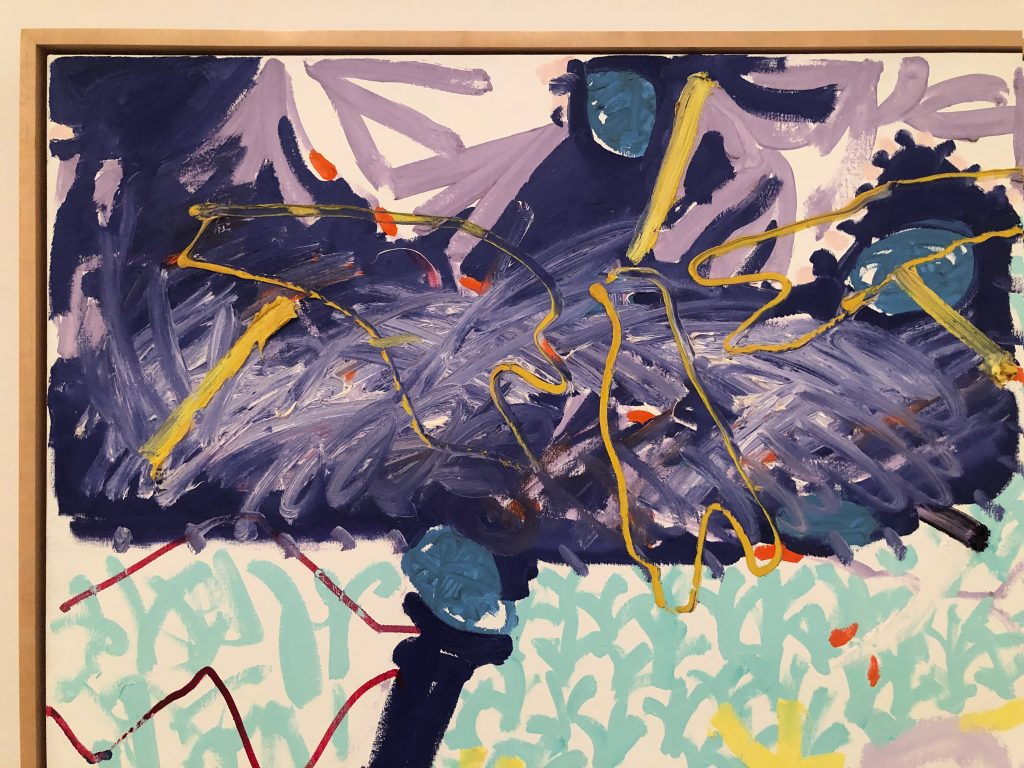

Patrick Heron, Detail of ‘Big Complex Diagonal with Emerald and Reds: March 1972-September 1974’, oil on canvas, 208.3 x 335.3cm

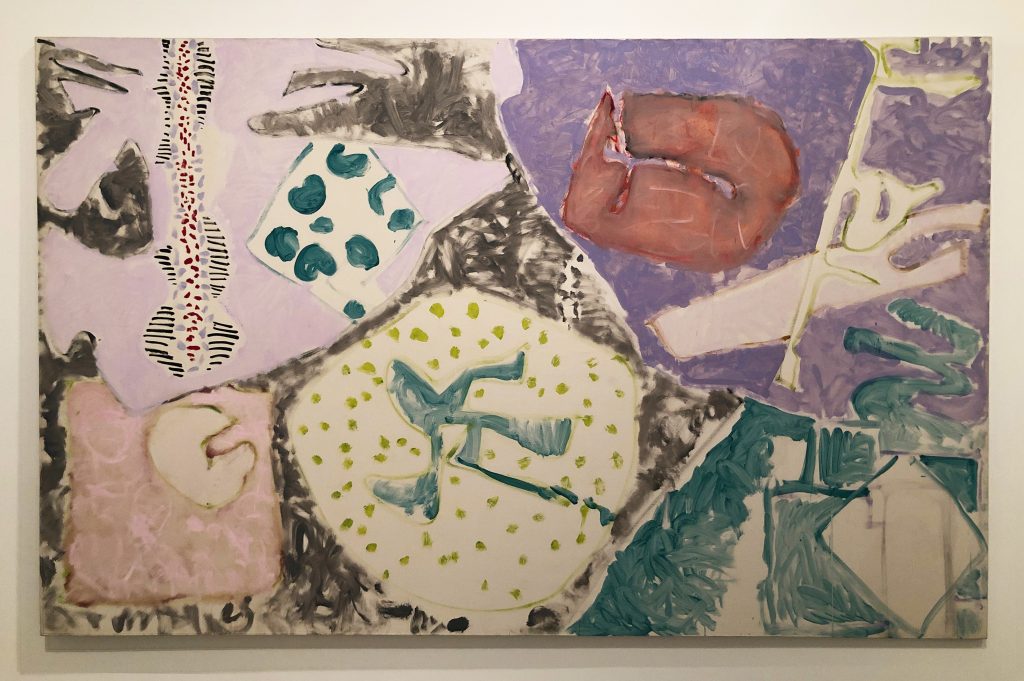

The hand whose traces Heron had worked so carefully to efface in the ‘wobbly hard-edged’ works (traces only detectable at close quarters in Margate, when the top-lighting in the galleries gleamed on the dried residue of oil medium in the looping, swirling brush-tracks) declares itself again in the paintings of the late 1970s and the 1980s, with an accompanying sense of re-engagement with all the varied possibilities for painting’s facture that Heron had set aside. The forms, and their disposition, in the new paintings correspond closely to those of the hard-edged works: the wonky ovals with their inset harbours and inlets, the crankshaft shapes, the attenuated, wriggling fronds, coming together in vertical stacks that abut the canvas sides, or divide the picture surface into interlocking zones of crazy paving; but Heron is once more running the whole gamut of ‘hand-done paintwork’ in a manner that feels like a re-capitulation of his entire career as a painter: As James Faure Walker observed of these works, ‘Sometimes he seems to try and recall every phase of his development in the one painting.’ 15‘Patrick Heron: the 1970s’, Faure Walker, J., in ‘Patrick Heron’ Barbican Art Gallery, 1985, p17 The results, such as ‘Pale Garden Painting: July-August 1984’ show Heron at his most beguiling: the colours are muted, but Heron coaxes an extraordinary low-level luminosity out of the entire picture space, laying the paint down in rough zones of thinned scribble over white priming; and the scrawled calligraphy of light pink over the pale rectangle in the bottom left corner seems to spread a kind of confectionery sweetness into every part of the painting. These are easy paintings to enjoy, and they drew audible sighs of relief from commentators who had looked to Heron as a standard-bearer for a certain idea of ‘good painting’: he no longer appears to be implementing an exclusionary agenda in pursuit of pure, refined colour sensations, but relies once more on rapid, free improvisation from first marks to last; plus, in works like ‘Sydney Garden Painting: December: II: 1989’ he further demonstrates his new openness to concerns other than pure opticality by taking the (for him) unheard-of step of painting with thick impasto.

Patrick Heron, Detail of ‘Sydney Garden Painting: December: 1989: II’, oil on canvas, 152.4 x 213.4cm

Signs for seeing, signs for things seen

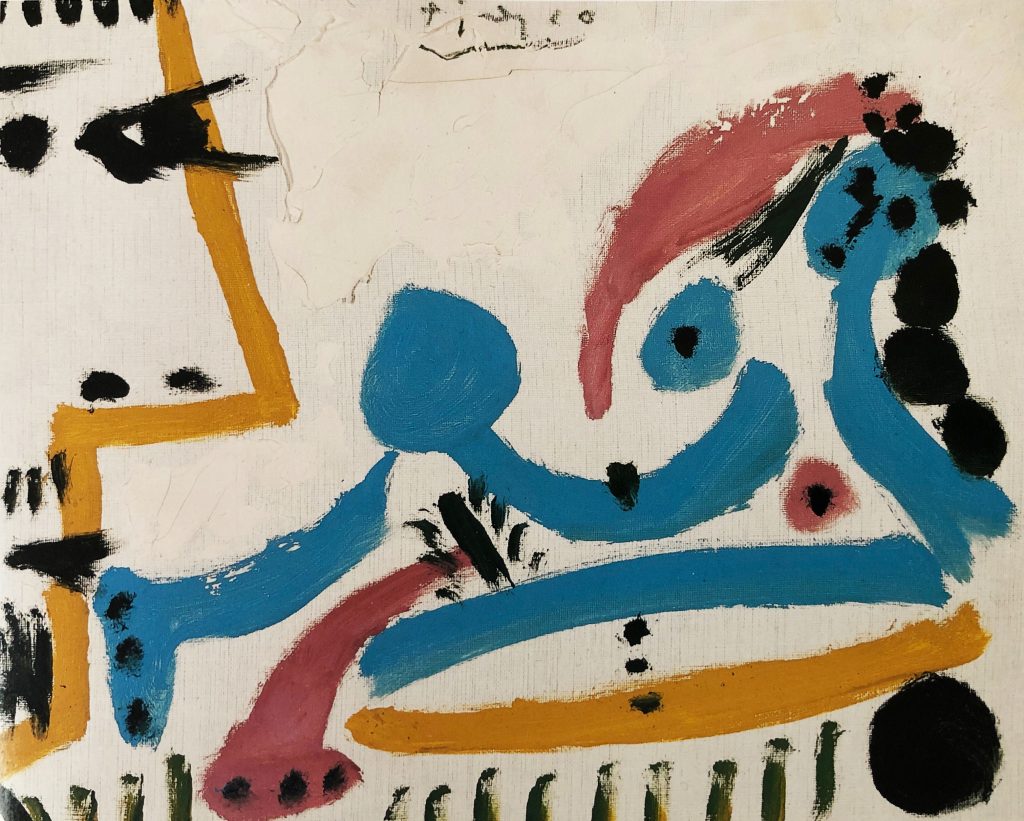

These works mark a return for Heron; but not a final destination. The last phase of his painting, when it arrived, announced itself in much the same way as the ‘wobbly hard-edged’ works did as they superseded what went before them, through a stripping-down of formal means, and a sense of travel in one very particular direction; with the key difference that whereas before, he had suppressed the visible work of the hand in favour of a concentration on colour, now, with ‘13th March 1992’ and ‘10th-11th July 1992’ it was clearly colour that was being suppressed, and emphasis falling instead on the slap-dash handwriting of drawing with the brush and tube-nozzle to an extent that seemed to re-cast the canvasses as something more like vast white notebook pages, and the marks on them as the rapid notations of a sketch. This, however, was not the operation of a kind of ‘Newtonian physics’ in Heron’s practice, by which an action (his concentration on colour in the hard-edge paintings) had elicited its equal and opposite reaction; it was much more. In fact, to understand the motivation behind this last shift in his painting, it is necessary to understand the extent to which Heron had been influenced by the last decade of Picasso.

Thrilled- and deeply moved- by the showings of Picasso’s late paintings in London and Paris during 1988, Heron had published a contemporaneous essay in Modern Painters that enumerated his enthusiastic responses to the work in blunt and surprising terms:

‘Labia, anuses, penises, nipples, armpit hair (like toothbrush heads), testicles, fingernails, eyeballs, eyelids, eyelashes (little mascara brushes), nostrils, not to mention interlapping lips- brilliantly economical signs for all these familiar parts of the human bodily furniture positively litter the surface of the[se] very remarkable paintings…’16Heron, P., ‘Late Picasso’, Modern Painters, Vol 1, No.2, Autumn 1988, p6

What was Heron- by this point, an abstract artist for nearly four decades- doing, fixating on figurative content with such obvious relish? He had gone on the record in the early years of his move into abstraction, asserting that ‘there simply is not available at the present moment, it seems to me, a valid figure, or figuration, which is not retrogressive in some way or other’;17 Heron, P., from ‘Five Americans at the Institute of Contemporary Arts’, ‘Arts’ (New York), May 1958, reprinted in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988, p33 what had changed for him? The clue lies in Heron’s phrase, ‘brilliantly economical signs’: he had grasped that Picasso had found his way to a system of notations for the things of the physical world, so spontaneously generated by the brush that they acquired thinghood; and that their inclusion in his paintings was an act of presentation rather than representation. In this way, Picasso refrained from committing what Heron had once termed ‘the heresy of realism’: his painted signs were not images, but a new species of ‘superbly exciting facts’. As Heron went on to write: ‘They are matters of fact (paint there on the canvas before your eyes) not of fantasy (ie., something invisible inside your head).’18Heron, P., ‘Late Picasso’, Modern Painters, Vol 1, No.2, Autumn 1988, p7

Heron’s late works are problematic: not in the way that the ‘wobbly hard-edged’ paintings had been problematic, by courting a kind of frozen perfection, but in their highly provisional, exploratory forays into the new territory that Picasso seemed to have opened up for him. He had, in Mel Gooding’s words, ‘achieved a contract with the natural world and its objects that allowed him the utmost freedom to create images that derived from the apprehension of resemblances rather than the imitation of appearances’.19‘Patrick Heron’, Gooding, M., Phaidon Press Ltd, 1994, p239 Although Heron still made a good many paintings that included high-keyed, generously-applied colour, the paint is delivered via explosive flurries of notational drawing– lines, scribbles, scrawls, dots, dashes; and there are as many that offer no easy treats for the eye, in the sheer scarcity of their paint, and in which the marks- such as the scratchy dark blue ‘grass’ at the base of ‘27th August 1991’- can feel like the product of joyless, half-mechanical activity, but also, as in the case of the utterly unambiguously referential leafy branch in ‘10th-11th July 1992’, like undigested chunks of figuration. What he was seeking, perhaps, at the very end of his working life, feeling his way forwards with very little thought for revisiting the crowd-pleasing opulence of colour and handling of the previous decade, was the form of notation that would allow him to speak an equivalently blunt language of ‘facts’ to the one evolved by Picasso. This search is most succinctly shown in the show’s small, simple ‘Vermilion and Ultramarine: June 11th 1985’, considered alongside one of the countless canvases of an equivalent small size that Picasso painted during his last decade of astonishing production: ‘Nu allonge et tete d’homme de profil’ of 1965 is a set of signs for things seen; Heron’s little canvas is a set of signs for seeing. And the distance between them seems barely any distance at all.

Patrick Heron, Detail of ‘Christmas Eve: 1951’, oil on canvas, 182.9 x 304.8cm

Patrick Heron, Detail of ‘Four Blues with Pink: July 1983’, oil on canvas, 96.5 x 121.9cm

Patrick Heron, ‘Four Blues with Pink: July 1983’, oil on canvas, 96.5 x 121.9cm

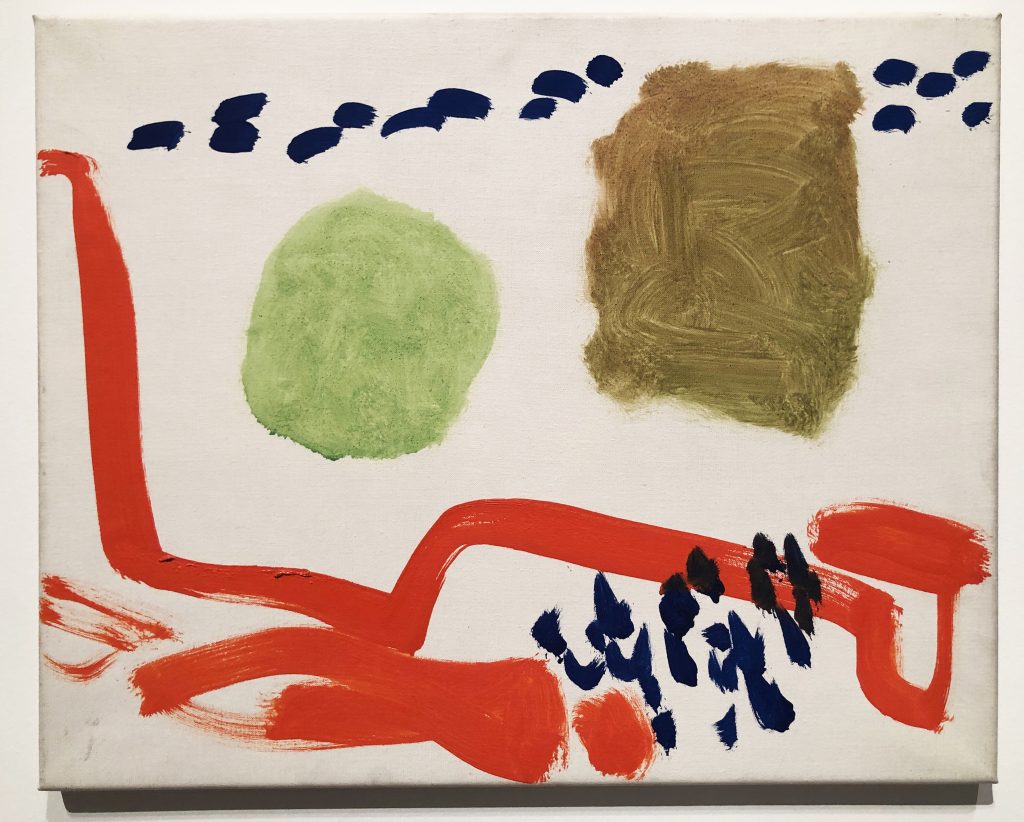

Jonathan Lasker, ‘Art and Meaning’ (2015), oil on canvas, 30 x 41cm

Patrick Heron, Detail of ‘Pale Garden Painting: July-August 1984’, oil on canvas, 205 x 330cm

Cooke, R., ‘Brilliant, Colourful, and Completely Out of Order’, 20th May 2018, http://theguardian.com

Faure Walker, J., ‘Patrick Heron: the 1970s’, in ‘Patrick Heron’ Barbican Art Gallery, 1985

Gooding, M., ‘Patrick Heron’, Phaidon Press Ltd, 1994

Gouk, A., ‘Recent Paintings’, in ‘Patrick Heron’ Barbican Art Gallery, 1985

Heron, P., ‘A Note on my Painting: 1962’, Catalogue of Galerie Charles Lienhard exhibition, Zurich, 1963, reprinted in Art international, 25th Feb 1963; reprinted in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988

Heron, P., ‘My Painting Now: 30th August 1987’, p19, in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988

Heron, P., from ‘Five Americans at the Institute of Contemporary Arts’, ‘Arts’ (New York), May 1958, reprinted in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V. Lund Humphries 1988

Heron, P., from ‘Two Cultures’, Studio International, December 1970, reprinted in ‘Patrick Heron’, Ed. Knight, V., Lund Humphries 1988, p35

Heron, P., ‘Late Picasso’, Modern Painters Vol 1, No.2, Autumn 1988, pp7-11

Newman, B., ‘The Sublime is Now’, Tiger’s Eye Vol 1, No. 6, December 1948, pp51-53, reprinted in ‘Art in Theory 1900-2000’, Ed. Harrison, C., and Wood, P., Blackwell Publishing, pp580-582

Power, K., ‘Looking at Lasker: The Surprise of Syntax’, in ‘Jonathan Lasker: Paintings, Drawings, Studies, 1977-2003, Museo Nacional, Centre de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, 2003, p35

7 thoughts on “Matt Dennis on Patrick Heron: Signs for Seeing, Signs for Things Seen”

Comments are closed.

Excellent review… PH was also v struck by seeing Matisse’s ‘Bathers Chicago’ in about 85… but tended to see Matisse’s reworking as sort of visual effects…. because he gradually eliminated revisions of any kind… I think.

What a brilliant essay! I had not picked up Heron’s influence from Picasso, totally out of character for those who knew him. Bonnard, Vuillard, Matisse yes, but the brutal expressionism of Picasso, not in a million years. I haven’t seen either show, but spent reasonable amount of time with the man to know his proclivities. The last time was at Kingston’s Picker Lecture, where his obsession with Greenberg had reached an unhealthy measure of malice. However, as with the Albert Irvin show, the association with American Painting, even when rejected, as in Heron’s case, made him an exceptional artist of note.

Yes, great essay. Thank you. I saw the St Ives show only, so can’t compare with the Margate hang. But totally agree about the notice boards, they were boring and detracted rather than elucidated. Have you had any reaction from either gallery to your comments? I emailed the Tate St Ives and pointed them in the direction of Instantloveland, but wasn’t even acknowledged. To move on to the man himself – what a treat to see the paintings again, familiar after several visits to St Ives, beautifully displayed on this website. And Matt Dennis’s perceptive and reasoned observations have thrown such a new light upon the paintings, my view of the work and of that of others mentioned who played their parts in the awesome mayhem of 20th century painting has, I think, been changed forever. The drama of painting rather than the painting of drama!

Cultural context. I’m just letting Instantloveland know that Abstract Art has been hijacked, stolen from under our noses. I made the mistake of attending the Symposium in Bristol entitled ABSTRACT ART NOW. That does not seem an ambiguous title. It was in the beautiful galleries of the RWA, in the midst of a wonderful exhibition by Albert Irvin, that also includes Pollock, Barnett Newman and Hoyland. However, the 6 speakers spent all day not referring to the work on the walls once. Three huge screens had one word on each: Context, Intentionality and Semiology. Why has the academic community hijacked Abstract Art for their, in the most part, tedious theorising? I wanted Albert Irvin and John Hoyland to return from their rest to rescue us from words, so many of them. The paintings on show offer a imaginative leap into other worlds where the torch of reason may not function. To approach Abstract Art as a naughty child that needs cleaning up invites the whirling dervishes of Surrealism to play havoc with such rationality.

I agree. A brilliant article. Congratulations. I’m not so bothered about the hang, as it does illustrate the self reflexive nature of Heron’s development, but I also agree about the forward momentum and its sudden leaps. I’d quarrel only with “crowdpleasing opulence”. I think you underestimate the extent of the hostility to Heron’s painting from the journalistic hacks who mediate Art to the public. I recall one such at the time of his Tate retrospective in 1998? The heading was ‘The King and the Court Jester’, the King being Lucian Freud, and the Jester Heron. This from I think John McEwan. And his writing didn’t fare much better, drawing ire and hostility in equal measure from establishment punditry. As with Roger Fry, it has spectacularly failed to change the perennial mindsets of the English curatorial world, the cult of eccentricity of personality, theatre and lifestyle, which now takes the form of socio-political activism as avantgardism.

Some terrific discussion about this article by Alan Gouk on abcrit@wordpress.co.uk. who correctly notes what a dense and illuminating article this is. Does anybody know if the Heron show is finishing at Tate Britain?

Great article , I met Patrick several times and found him inspirational . Congratulations