Laura Davidson writes on Susanne Nørregård Nielsen

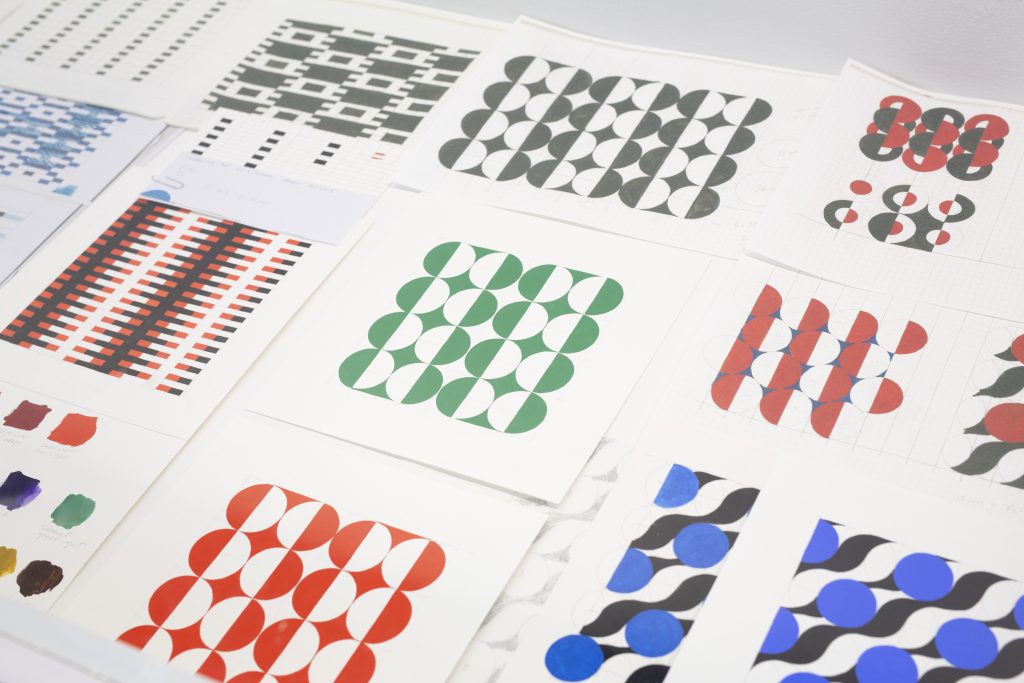

Susanne Nørregård Nielsen, working drawings for ‘Pencil to Paper’ (2018), pencil and gouache on paper, dimensions variable

Susanne Nørregård Nielsen appropriates what is only briefly touched on in almost all histories of Modernism: work by female artists, specifically, work that utilises textile-based practices such as embroidery or weaving. Two years ago Nielsen, a painting lecturer at Glasgow School of Art, was reading Walburga Krupp’s1Walburga Krupp is a research associate at Zurich University of the Arts. essay, ‘Try, try…! Variation of a ‘true artist’’ (2002) when a footnote on Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s article ‘Remarks on Instruction in Ornamental Design’ captured her interest: originally published in 1922 by a Swiss crafts magazine, Taeuber-Arp’s text details eight instructions for making art. It begins with the statement: “if you want to practice design then you might want to try the following”. This text became the catalyst for her exhibition ‘Pencil to Paper’ at Glasgow International 2018. Using gouache and pencil, Nielsen revived these instructions, in order to create eight new works that bring Taeuber-Arp’s contribution to early Modernism to a new audience.

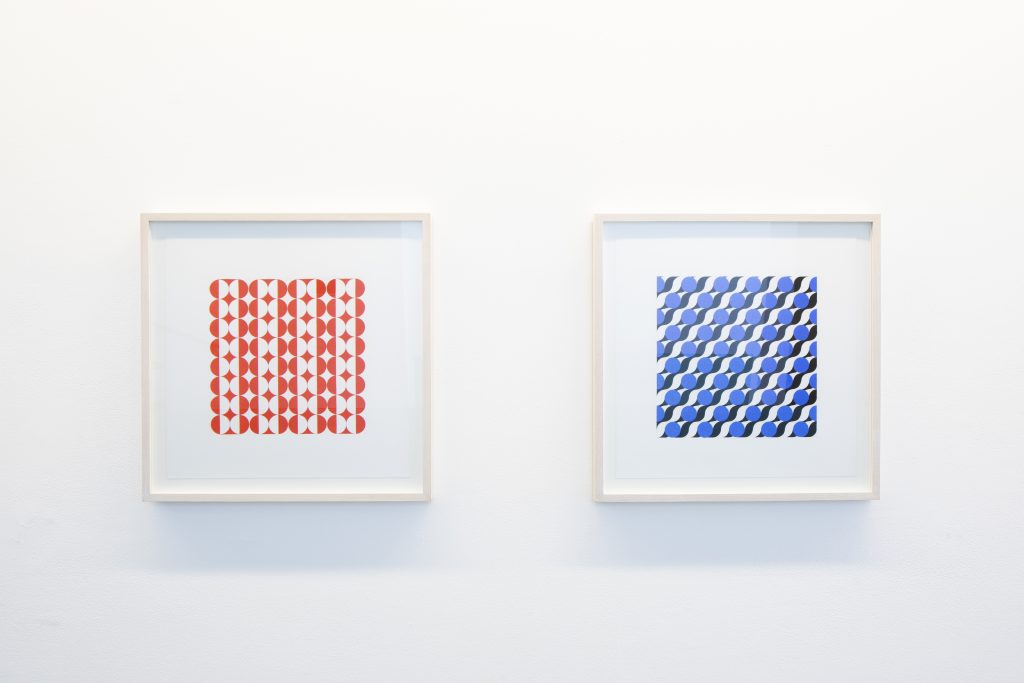

Nielsen’s primary explorations generated a considerable body of work, including iterations of the final eight drawings, neatly laid out in a pair of display cases at Glasgow School of Art. For Nielsen, the first two weeks of working with Taeuber-Arp’s text was a period of doodling, thinking and drawing –“going back and forth and seeing what fits”, as she found her way into this very precise way of working. In fact, Nielsen stated that the way she interpreted the instructions was similar to the way one would interpret Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings. She commented that the circles came relatively quickly, and the more angular work followed. In conversation, Nielsen has reflected that working with the instructions brought a very particular insight into Taeuber-Arp’s philosophy of art. Moving between reading Taeuber-Arp’s instructions and looking at Nielsen’s work, there is a sense that whilst the individual instructions appear relatively open to interpretation on the surface, there is a certain rigour in the actual sequence or rhythm of instructions.

Pleasingly, the eight instructions can be symmetrically divided into two halves, with each set of four divided into two to form a framework for a particular type of drawing. The second drawing in each pair has a relationship with the drawing that comes before it, and this arrangement suggests that Taeuber-Arp was proposing that her readers reflect on their drawing through the medium itself. The first instruction (“Draw a square and try to divide it in its most natural and simplest way, so that you can use those forms or division lines as decoration”) cascades into the second, (“A further exercise is trying to divide it in a more complex way and paint the different fields with two or three colours”), and so on. Nielsen stays true to this rhythm by pairing her drawings together in accordance with Taeuber-Arp’s rules: and the resultant flow allows the viewer to read ‘Pencil to Paper’ as a sequence, rather than isolated pieces.

As well as textiles, drawings, painting, collage, interior and set design, dancing and performance also form part of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s extensive oeuvre. Born in 1889, she began to study under the choreographer Rudolf von Laban in 1915, and by 1917 she was working in the department of form at Laban’s school, alongside her position as a textile design tutor at Zurich’s Trade School. Laban is known for inventing Labanotation, a notational system for dance, in 1928; and indeed, it could be argued that Taeuber-Arp’s ‘Remarks…’ has a choreographic sensibility to it. The parameters of the stage are defined by the person interpreting the instructions, whilst the movements and rhythm are defined by Taeuber-Arp’s instructions. The very idea that a ‘finished’ drawing could be the basis for another drawing is reminiscent of the way a dance will build up sequences of movement as one gesture leads to another, then another, sometimes repeating, increasing with intensity or dissolving; and this kind of movement is evident across Nielsen’s work in ‘Pencil to Paper.’

It is intriguing how Nielsen’s identity fades in and out of the work, where her role as an artist crosses over with that of a curator, art historian and archivist. It is in considerations of colour and pattern where her authorship is very much apparent. Talking about her use of colour, she spoke of playing with a “negative space which removes the geometric outlines that we can process with ease” and remarked that having a “clear understanding of fabrics and patterns created drawings that give room to move in and think.” Despite having a practice rooted in painting and the histories of painting, much of her research-led practice has to do with thinking about the ways in which textile design influenced early abstraction, and how the development of modernist textiles influenced modernism as a whole, despite the fact that textile design was at that time widely held to be a lesser art form than painting. In her own words, Nielsen’s “central research enquiry illuminates artworks central to the early 20th century canon, particularly Mondrian and Malevich, to promote new thinking on the impact of artists’ practice using feminine gendered materiality.” For Nielsen, this is of particular relevance, given the historical lack of recognition of Taeuber-Arp’s textiles, born of a widespread perception that “feminine gendered materiality” would undermine the rest of her legacy; the same lack of recognition that led to ‘Remarks…’ being published in a crafts magazine, as opposed to a traditional art publication.

Susanne Nørregård Nielsen, Installation view of ‘Kites and Suprematist Dresses after Malevich. Red Yellow Blue’, DCA Dundee Contemporary Art, 2009

Nielsen’s previous research into modernist textiles has led her to appropriate and recreate Malevich’s three dress designs of 1923, which clearly reference Suprematist philosophy; interestingly, Nielsen has pointed out that Malevich used embroidery in some early Suprematist works. Malevich’s dresses can be seen in a series of photographs Nielsen published in Source magazine in 2006, where she is captured jumping from the ground whilst wearing them, referencing his interest in flight. Four years spent learning weaving with Jan Shelley2Shelley is a weaver and the former Head of Textiles at Duncan of Jordanstone School of Art in Dundee. have also given Nielsen insights into Anni Albers’ chosen ways of working: employing the same methods that Albers would have used offers a different perspective from that of a traditional text-based historical analysis. The influence of weaving can also be seen in ‘Pencil to Paper’ as the forms take on a warp and weft effect.

Further research into the canon of 20th-century Modernism led to ‘Flowerbed’ of 2007, which unearthed a series of botanical watercolour and ink studies that Mondrian made, alongside his abstract work. Having ascertained through her research which species of flowers Mondrian had studied, Nielsen planted examples of them at St Andrews Botanic Garden: the subsequent photo-documentation depicts rows of flowers planted in a geometric pattern. Writing about the exhibition, Sarah Smith, Head of Fine Art Critical Studies at Glasgow School of Art, states that “ ‘Flowerbed’ […] ‘breath(es)’ life back into a significant but overlooked aspect of Mondrian’s oeuvre and stages a series of conflicts that articulates both the ambivalence of his practice and the discord it creates for the dominant story of modern art as one of evolutionary progress.” Re-presenting this history could be seen as controversial; it causes a rupture in the public-facing image of an artist whose work is indexed as a definition of Modernism. The idea that Mondrian’s identity could be multifaceted, and that he could be interested in the implied triviality of flowers challenges the legacy that has been constructed around him. ‘Flowerbed’ highlights this failure on the part of Modernist art history to embrace difference and divergence.

Susanne Nørregård Nielsen, Installation view of ‘Mondrian’s Flowerbed, Summer’ at St Andrews Botanic Garden, 2007

Nielsen has revealed that after Taeuber-Arp’s untimely death in 1943, her husband, Hans Arp3Hans Arp was also responsible for the posthumous completion of some of her work, as seen in the catalogue for ‘Today is Tomorrow’ (2014)., was reluctant to show too much of her textile practice for fear it would devalue her other work. The textiles stayed in the background until the 2014 exhibition ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Today is Tomorrow’ which showcased her as an artist working across disciplines, presenting her extensive textile work as equal in importance to other aspects of her practice. Nielsen’s work is a continuing revitalization of this legacy; and in her further tenure at the archive4This research is supported by the Arp Foundation in Berlin. Nielsen is the second artist to receive an ARP Research Fellowship. she will be looking at the collaborative embroideries created by Arp and Taeuber-Arp. Beyond this, Nielsen hopes to work from Taeuber-Arp’s eight colour theory rules, which are apparently “quite far out!”

In writing this text, I have become conscious of the ambiguity in my use of ‘she’ and ‘her’: is it Taeuber-Arp I am referring to at any given point, or Nielsen? This ambiguity is echoed by the way in which Nielsen’s practice-led research blurs the boundaries between herself and Taeuber-Arp, thereby emphasising the collaborative nature of the work, and indeed, the collaborative nature of art history. ‘Pencil to Paper’ has been a conduit for the revitalisation of Taeuber-Arp’s legacy, but Nielsen’s wider practice deals with histories that do not fit the dominant narratives of modernism, particularly when they feature artists whose work has widely been considered the definition of what modernist art might be, such as Malevich or Mondrian.

Before I left the exhibition, Nielsen handed me a piece of paper filled with insightful notes on her practice and research. At the top is a quote from the American writer Siri Hustvedt: “Art history always tells a story. The question is: How to tell the story? And how telling the story will affect my looking at and reading of the painting?” (p.9, 2017) Nielsen attempts to answer these questions by looking at artists whose chosen medium has been eclipsed by painting’s perceived pre-eminence in the canon of 20th century modernism; and she has astutely woven other histories into this canon to affect our looking at, and reading of, painting itself.

Douglas, C. (2006) Up, Up and Away! Malevich Takes to the Skies: Charlotte Douglas Introduces the Work of Susanne Nielsen, The Photographic Review, Spring 2006 (46), pp. 4–11.

Hustvedt, S. (2017) A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women: Essays on Art, Sex and the Mind, London: Sceptre

Meschede, F and Schmutz, T. (2014) Sophie Taeuber-Arp-Today is Tomorrow, exh.cat. Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess.

Smith, S. (2007) Re-framing Mondrian’s Flowers, exh. pamphlet.

Susanne Nørregård Nielsen, Installation view of ‘Pencil to Paper’ at Glasgow School of Art, 2018

Susanne Nørregård Nielsen, Installation view of ‘Pencil to Paper’ at Glasgow School of Art, 2018

Susanne Nørregård Nielsen, working drawings for ‘Pencil to Paper’ (2018), pencil and gouache on paper, dimensions variable

Susanne Nørregård Nielsen, working drawings for ‘Pencil to Paper’ (2018), pencil and gouache on paper, dimensions variable