In the second of Instantloveland’s new series of interviews, John Bunker discusses materiality, mark-making and abstraction in the Instagram Age with artist Howard Dyke…

Howard Dyke (b.1971) studied painting at Central St Martins from 1990-93, before studying Fine Art at Goldsmiths College from 1999-2002. He works mainly in painting and collage; he has exhibited in London, New York, Prague and Beijing, and his work can be found in many private collections, such as the Saatchi Collection, Simmons & Simmons, and David Roberts. He currently lives and works in London.

JB: Can you remember the first abstract painting to make a real impression on you?

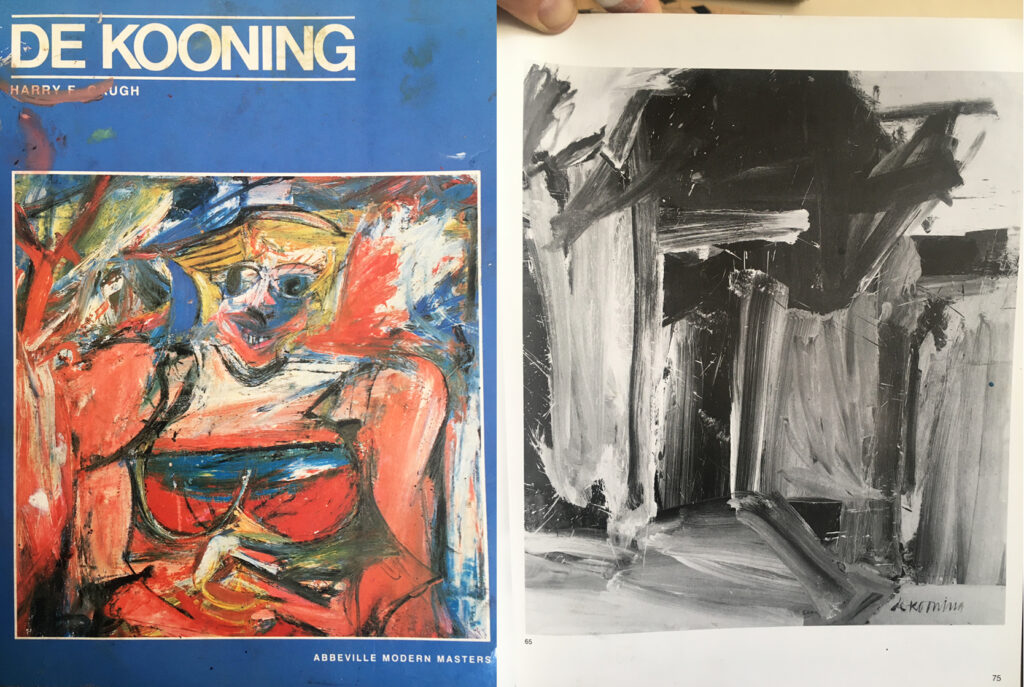

HD: Possibly De Kooning’s ‘Door to the River’; but that was out of a book I use to pore over at college. Frank Stella and Helen Frankenthaler were in the room too.

JB: Do you see yourself as an abstract artist or as an artist who works with aspects of abstraction? And what does working abstractly offer you?

HD: I don’t really see myself as an abstract artist, or as involved with the purity that comes with that role, because I work from found images and still see myself as a picture-maker of some sort, even if the pictures I produce are not read in the narrative sense and aren’t always easily deciphered. The figure plays a big part in this.

I never liked the ‘abstract artist’ tag; it always seemed a bit pompous to me, and just a disguise for saying ‘I’m going to offer you very little in terms of a way in here, and you can take it or leave it.’ Saying that, I do love abstraction, but even abstract images seem rooted in the everyday to me. When I look at the world around me, I want to pare things down and bring those ideas back into the studio to see how they can be communicated through material gesture. I definitely reference abstraction, I know that much, but it’s never been my aim to make an abstract painting.

Abstraction offers me a way in, and, eventually, a way out. What I mean by that is working abstractly allows me to break down an image and reassemble its component parts. The paintings are pushed through many processes and I’m trying to arrive at an image more quickly. I’ve finally got the material in the studio to be able to do this now, which is very liberating.

JB: Collage seems to be a central component of your approach to painting. How has that come about?

HD: Yes, very much so. I like the physical aspect of it; the wear and tear the elements go through before finding their place in the painting. It’s also a way of bringing together materials that jar against each other.

JB: Your recent work has tended to be big and comprised of a great many different materials. Why so?

HD: I call these works ‘Physical Collage’ as the pieces are so large, that is, human size; and my brush is often a staple gun. Collage allows me to move the parts of the painting around, so that the image can be ‘de-spaced’ and skewed through a rupturing of the surfaces.

Picking up a two-metre piece of painted material and laying it over an image you’ve just painted is exciting. The possibilities are infinite. An artist I know asked me why I feel the need to change paintings, often significantly, and why don’t I just leave the paintings as they are? I said to him that I’m already looking past what I’ve just made and don’t want the easy option of form and colour in a nice composition. I like the mess and the problems. Throw some ugliness in there and I’m happy!

In these large works the utilitarian tarpaulins, for instance, are used to mask off an area whist I work on the rest of the surface, so I don’t over-layer and destroy parts I intend to preserve. Sometimes these ‘masks’ get stuck in the paint and I leave them on. I like the possibilities, the logistics of making large works from disparate elements. Scale is important insofar as the image becomes part of the viewer’s landscape. I make loads of small collages from remnants of larger works; it’s quite an economical process in that I hardly ever throw anything away. It all goes back into the mix.

JB: Although your work contains abstract elements, such as the grid, and non-representational, gestural application of paint, the figure sometimes materialises from cut-out shapes, before disappearing into the churning facture of the painting. Why are these references to the figure a feature of the work?

HD: The figure is a basis to hang the gestural marks and collage elements onto. The idea of the body, as physical matter moving through space, is central to my work. It’s why I made the early ‘Veil’ paintings – shrouded figures poured from cans of paint. I like getting up a ladder and dropping materials onto the paintings, creating accidental marks & abrasions; or tearing a piece of collage that’s already been heavily painted to reveal what’s underneath.

Large pieces of material migrate around the studio over a period of time, until they coagulate. I’m looking for realism, a reflection of what’s happening in the world. Matthew Collings described my work as obeying ‘The Law of Surprise’. I like that.

JB: So what exactly about ‘Door to the River’ made the impression, and why? In what way did you consider it an abstract painting?

HD: The material aspect of De Kooning’s paintings interested me; the building up of layers, each one seemingly obliterated to make way for the image to form. I’m looking at the reproduction of ‘Door to the River’ from the exact same book I had whilst at college in an attempt to glean some answers. The fact that the reproduction is in black and white gives the painting’s slashing brushstrokes and oversized slabs of paint an energetic graphic quality, a bit like Franz Kline’s paintings of the time; but whilst the De Kooning’s qualities felt hard-won to me back then, the Kline paintings looked too ‘easy’ somehow, perhaps because I was aware that he worked directly from small brush-and-ink sketches. I soon realised, however, just how difficult it really is to scale up mark-making and produce something that looks convincing.

The top right-hand corner of ‘Door to the River’ looks like the first day of the painting, and the ‘door’ painted on the last day De Kooning worked on it, gives a fixed space and point of focus through which to look back through the history of its making. As I mentioned earlier in our conversation, there’s a way in and a way out, in the sense that you could crawl in and then escape through the gaps between the brushstrokes.

JB: Perhaps seeing ‘Door to the River’ in black and white emphasised its construction? In your work I like to think I see the same kind of matter-of-fact constructing going on; in particular, I like the way quite delicate gestural painting is abutted by densely layered cut-outs.

HD: Yes, you’re right- very much so; and by seeing the image pared down to its tonal values and contrasts gave me an early mental blueprint of what I wanted to achieve. There was also a romanticism and a mystery, in the black-and-whiteness of that particular reproduction in the book, as if it shouldn’t have been there at all, due to some copyright infringement.

JB: And how did the influence of Stella and Frankenthaler- both of whom you mentioned- make itself felt?

HD: Thinking about Frankenthaler, I was wowed by the epic scale of the raw canvas substrate, and of its indelible blotted pigmented shapes which were also rooted in the figure and landscape- dynamic and light, yet physical too. They gave me a feeling which I could only describe as a kind of butterflies-in-the-stomach nervousness and excitement. It’s an excitement about how painting could come straight from the unconscious and envelop you, and an excitement about how building chance and accident into the process could be liberating. It made me feel excited about painting, about its endless possibilities that could be taken as far as one wanted. There’s always a new image out there. It just doesn’t know it exists yet.

Frank Stella’s early black stripe paintings were important to me because of his choice of materials: the utilitarian silver and copper paint. The holes cut into the canvasses made me re-think the paintings as object-versus-image, and understand the tension that could exist in the space between those terms. His later, loosely-painted ‘French Curve’ relief in aluminium honeycomb, were another early influence.

JB: There’s an interesting duality here: on the one hand, the freedom to explore the fulsome materiality of painting that can play with appearances (the figure, the machinations of the unconscious, and so on) and the paring-back of painting to its essential properties on the other. Do you think these modernist preoccupations with ‘purity’, with notions of the ‘fully abstract’ and with the materials of painting remain or linger on in your work?

HD: I think those modernist preoccupations are certainly there, and the obsession with materials is important in respect of making an image; but it’s funny, I’ve never really thought of myself as a painter, I just happen to make things that use paint and different substrates with a lot of glue to bind them together.

JB: I like that early statement of Stella’s: ‘There are two problems in painting. One is to figure out what painting is; and the other is to figure out how to make a painting.’ It’s interesting how he travelled from the rigorous interrogation of painting in such works as ‘The Marriage of Reason and Squalor’ to the outrageous and extravagant ‘Exotic Bird’ series. The latter feel overtly lyrical but still have that constructed objectness about them. Would I be right in saying that your focus on the materiality and constructedness of your paintings helps maintain a sort of tension between object and image?

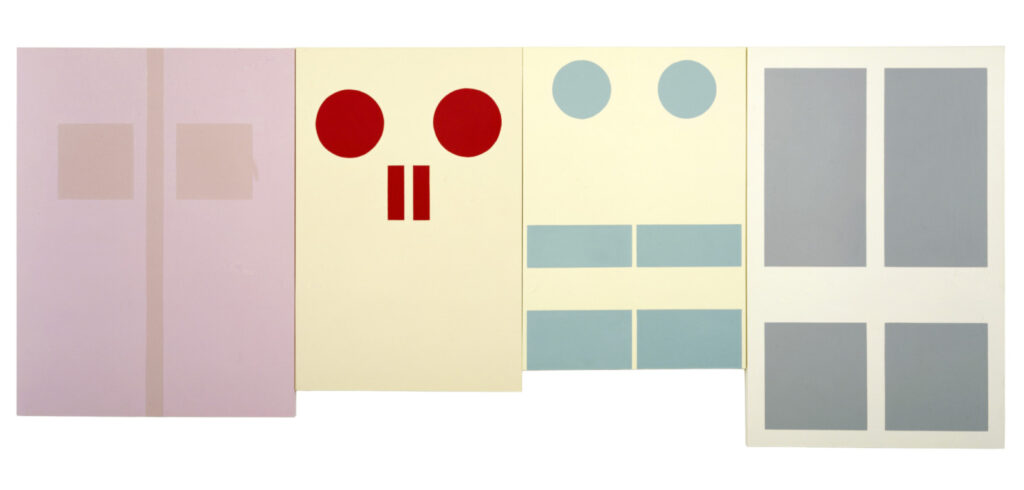

HD: The Stella quote is great. There’s also a Bruce Nauman quote where he says Stella was a great artist until he decided to be a painter. I think he was referring to the early ‘Black Paintings’ and the play between painting and object; after that Stella became, for Nauman, far too formal, with the introduction of colour, shape and monumental scale, which to him wasn’t interesting anymore. I tend to agree. I find the whole debate about painting and its history quite boring. I like Joe Bradley’s indulgent use of American painting’s history, post- 1950, in his work; but I’m more interested in someone like Sterling Ruby, who also quotes the grand scale of Newman, Rothko & Rauschenberg, even going as far as making Newman- style ‘zips’ from stripey coloured elastic, but moving way past these quotations on to a more critical view of American culture. He’s not so interested in the painterly dialogue that painters so love and get so fixated on, which I also find quite boring- even though we’re having this conversation around painting! But in terms of materiality and object and image, Gary Hume’s hospital door paintings had a big impact on me; and in terms of making contemporary abstraction out of old abstraction, Keith Coventry’s work also comes to mind.

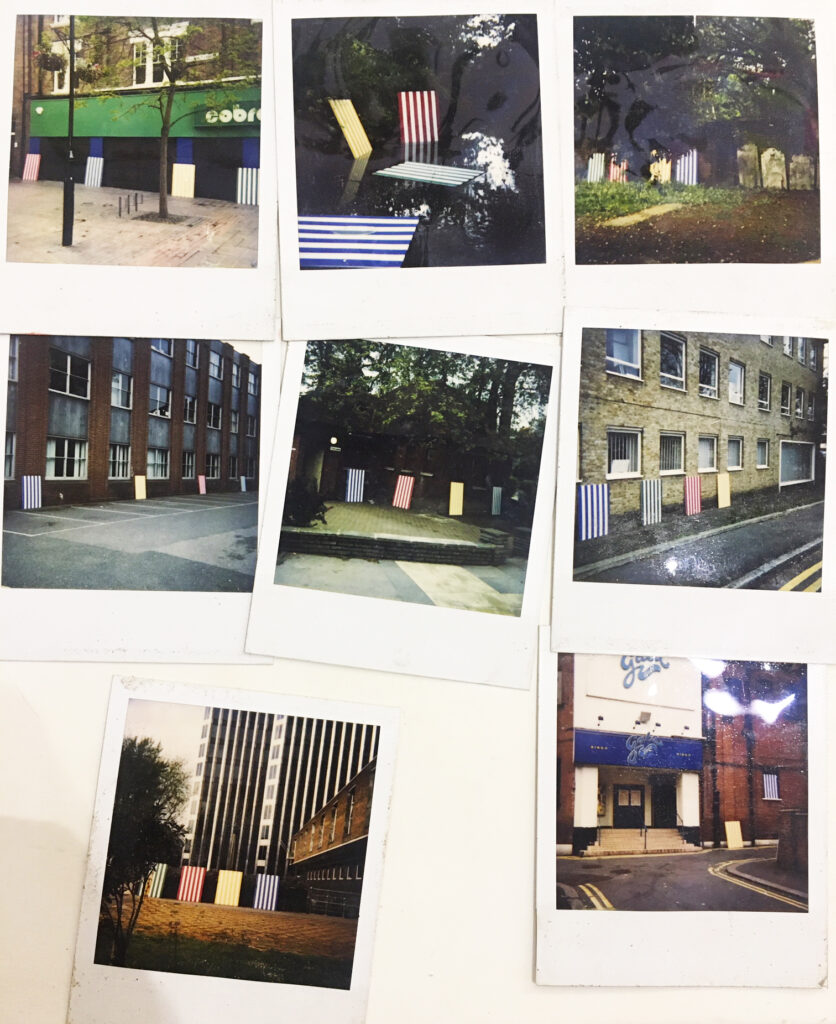

JB: Would you agree that Hume and Coventry and many other painters who came up in the ‘YBA’ era were rubbing that utopian aspect of abstraction (especially the geometric constructivist sort) up against a sad and pale contemporary reality? Do you see Hume and Coventry as making a critique of the socially and politically transformative aspirations of a certain strain of abstract art? Do we all now see that utopian abstract art as a kind of embarrassing failure? I ask all this because I have really enjoyed seeing your Instagram posts in which large works appear in basketball cages or are leant up against abandoned vehicles on city streets. Could you talk about this re-contextualising of how the paintings are displayed?

HD: Hume’s ‘Hospital Door’ paintings can be understood as re-stagings of the colour-based painting of Albers and Rothko framed within the geometry of an institutional door. I love the ‘Door’ paintings, and I never saw them as being cynical about abstraction; for me, they are as sublime as the historical instances of abstraction he was quoting. Each coat of gloss in these paintings, sanded down, is an intensive labour of love, and in a sense a time-lapse of life, an attempt to transcend the object through materiality and contemplation. Isn’t this true of what we’re all trying to do – make something that is more than the sum of its parts? In Keith Coventry’s critique of the social housing of the inner-city estate, social experiment is followed by social decline (through neglect), and then by a form of social cleansing through demolition; Coventry debases the highbrow Suprematist aesthetic whilst elevating the estate map through a transcendent use of materials; linen and oil paint embellished with a handmade painted frame. But these works are also about death, and moreover, death of the utopian ideal. For sure, I see myself coming from those urban influences. Leaning paintings on trucks or hanging them out to dry on basketball courts is my way of pulling the work out of the studio and seeing how it stands up, both literally and metaphorically, in the urban environment.

Does the painting look contemporary and alive because it’s leant against a truck? And does it add to the sense of unease I feel about making a painting? Am I just producing relics? I don’t know, but it’s a thing I feel I must do.

JB: I’m intrigued by the ‘unease’ you feel about making a painting. I sense an interesting ambivalence in what you say: you mention Hume’s ‘labour of love’ and the sublime aspect of the history of abstraction which he quotes, and yet you find the ‘painterly dialogue’ between painters boring…

HD: Let me go back for a moment to the sculptures I did and didn’t make in that brief period at Goldsmiths. I had ideas for public sculptures and interventions in the urban environment, weird mash-ups of objects and ideas, and I’d write these down in a crude word-processing programme with different colours and fonts, with each choice of font and colour linked to a particular idea. Some were poems with drawings, others just descriptions of what I wanted to make; but few actually got made. The ones that did get made were pieces using light. As I got further into this way of working and the ideas became more skewed and abstract, it became more and more evident that I couldn’t find a way of realizing them; it would have meant applying for grants and hassling people for money, and by the time that process had run its course, the ideas would have been dead and buried, meaning I would have once again run into a cul-de-sac. At the time there was huge trauma in my life and I was adrift with no fixed anchor point, a state of affairs reflected in the work I was making. It was at that point I decided to go back to basics and work on images I’d collected. And eventually this led to my starting to paint again.

JB: Why did you turn to sculpture and conceptual art? Why did these aspects of your work not ‘get off the ground’? And then, why did you return to painting?

HD: Good questions. I applied to Goldsmiths with some quite illustrative paintings and a little set of Polaroids which, I think, in the end got me a place. These Polaroids documented a group of Daniel Buren-influenced paintings made from striped awning fabrics (red and white, blue and white, yellow and white, green and white) which I took on the train out to the north-east London suburbs where I was brought up and placed in the entrance of a derelict bingo hall, and amongst the gravestones in a leafy churchyard; and in little installations, one outside the brutalist 1960s Civic Centre and others scattered across the town. There wasn’t much contemporary culture there when I was growing up, so I think this was me trying to bring a little bit of what I’d learnt back into the area.

JB: With Buren context and site is all. He produced simple, direct images; or, as some might say, repetitive and blank ones. You are about the ‘Law of Surprise’, and you have described yourself as ‘a picture-maker of sorts’.

HD: I now see it as the start of what painting could be for me. I didn’t find, and still don’t find painters talking about the mechanics of painting that interesting, as it can stop them testing the parameters more. Paintings made for Instagram, perfectly placed, documented images that look like how paintings are meant to be, could be interesting if there was some kind of criticality involved, but their presentation always feels a bit repetitive and lazy. Still, social media are a new and different set of tools, and a legitimate subject for discussion.

JB: Can I ask about the nature of the trauma you went through as you returned to painting?

HD: Whilst I was in the middle of my studies at Goldsmiths, my partner at the time sustained a serious brain injury in a climbing accident. She was in a coma, and the prognosis was a 50/50 chance of survival. Thankfully, she did survive; and we all nursed her back to a good state of health, but for three or so years in my late twenties I was visiting intensive care units, and then waiting months for her to finally wake up. When she did start to regain consciousness, she exhibited loss of movement, speech and any knowledge of who I was, or, for that matter, who anybody was. After two further years of visiting brain injury rehabilitation centres and working with nurses, therapists, physios and neurologists, she regained the ability to walk, and despite disability, reacquired a level of functionality no one had thought possible.

During this period, I was immersed in the body and the images of trauma that surrounded me. At the time I didn’t I really know what effect it would have on me in the long term; but afterwards I went through a very difficult period, coming to terms with the experience and the heightened emotional state I’d been in for all those years. I was lost, in a way, as I’d given up so much energy and didn’t quite know where to go. I crashed, and it was at this point I decided to paint again. (The irony of it is that, a few years down the line, I had my own neurological problems that ultimately required surgery.) I still think these experiences of the body and its fragility feed into my work now, but maybe not so intensely.

With hindsight, I think that some of the paintings I made a few years later were a direct response to these feelings; in them, the veil covering the body was alluding to the hospital bed sheet or the operating theatre gown. And although I chose those images for their painterly qualities and formal energy rather than any political content, there was a sadness and violence to them that came out of all that I’d felt and seen during that time.

JB: Your having gone through this experience certainly casts your responses to Hume’s ‘Hospital Door’ paintings in a very different light! Might the term ‘abstract’, in the way you use it, be understood as a kind of ‘freedom of invention‘?

HD: Abstraction as freedom of invention? Definitely true. After that long hiatus whilst at Goldsmiths, when I started painting again I decided to go back to basics, which meant painting images that appealed to me in an abstract way, working from newspaper cuttings that looked like Rothkos, De Koonings, Frankenthalers, Klines, and painting them figuratively.

JB: Do you mean the imagery in the photographs looked like those artists’ abstractions and that you painted them in a photorealist style?

HD: No, not in a photorealist sense, but in a more compositional way. I’d collect these images that reminded me of abstract paintings so I had something to work with; this helped keep the momentum going and fueled the desire to go to the studio again. But that approach wasn’t enough to keep me engaged, so I cut them up and spliced them together with other elements such as polyurethane tarpaulins, quilts, printed fabrics, anything that would twist the narrative of the image and prevent it from being a ‘picture’. They became ‘things’ with pictorial elements in them; but skewed enough to become, in turn, patched-up ‘abstractions’. I was keen to give the paintings context, and offer the viewer a way in to them, by giving them titles that referred back to the magazine images I’d originally used.

JB: I can understand how the figure might assume central importance after this journey you’ve been on, and how Hume’s hospital door paintings might take on a whole other level of meaning beyond the quite possibly rather shallow political reading I brought to his work. That said, I’m very interested in your very recent works, in which you seem to be channelling overtly gestural painting. In them, the ‘physical collage’ element seems to be somewhat in retreat. Do you think this use of gesture is another way of linking that aspect of abstract painting to the human body without the more illustrational imagery dominating?

HD: That’s a good point, as I definitely had an idea how these paintings would look somewhere down the line; and I’m probably achieving that look now which worries me slightly as I don’t like to feel comfortable when I’m making art. It’s funny, as I’ve looked at a lot of the illustrative work I made 15 or so years ago; I’ve brought those sketches and collages back into the studio to work from again. Which is not to say I’m regurgitating old ideas; rather, I think it’s necessary sometimes to retrace one’s steps, in order to reclaim an essence of what you’re about, and remember what drove you to make paintings in the first place.