David Evison: ‘Modernist Constructs’: Margaret Mellis at the Towner Gallery, Eastbourne

David Evison, Berlin-based English sculptor with a foothold in St Leonards on Sea (just across the bay from Eastbourne) writes about the show of Margaret Mellis’s driftwood reliefs at the Towner Gallery that came down at the end of January 2022.

‘When I start putting pieces of wood together I am only aware of the colour-shape relations. I don’t have any idea what may happen on the way or at the end or whether I shall use the bits I started with or end up with completely different pieces. I am working in an abstract way, feeling the colour, shape, texture, size together. Something begins to happen, sometimes immediately, sometimes after a long struggle. When the thing finishes happening, there is something interesting that you didn’t know about before.’

Margaret Mellis wrote this in 1990. It is simple, erudite and condensed, and is the best statement by an abstract modernist that I know of.

Mellis had been a star student at Edinburgh College of Art, winning a scholarship to study for two years in Paris at the atelier of Andre Lhote, who had been one of the group of painters around Picasso, Braque and Gris, and who, in turn, passed the rudiments of Cubism on to his students. She moved on to the Euston Road School to complete her studies, meeting there, and subsequently marrying, painter and critic Adrian Stokes; and in 1938 they led the exodus of London-based artists (The Hepworth/ Nicholson family, Naum Gabo, Piet Mondrian, Roger Hilton) to St Ives, the better to make their art far away from the long-expected bombs. Her marriage to Stokes having ended, she moved to Cap D’Antibes with Francis Davison after the war was over, returning after two years to settle in Suffolk.

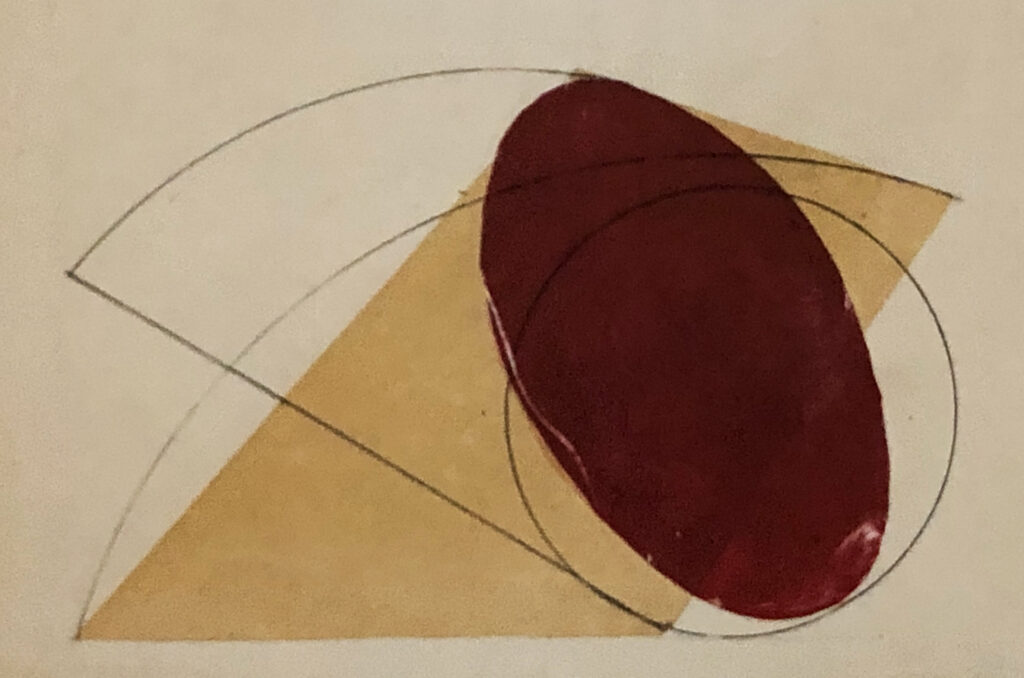

The Towner Gallery show, which came down at the end of January, offered us a few paintings made in London before her move to St. Ives; and in these there were already signs of a sensitive colourist who had clearly paid close attention to Bonnard. The two small, cubist-style still lives showed that she had thoroughly absorbed Lhote’s teaching (although her bright colour vies distractingly with the taut, rigorous drawing she employs in the attempt to control it) and the accompanying pair of Gabo-influenced collages from her St Ives period were so good that she could have conjured an entire career from these beginnings.

She didn’t; instead, as ‘Modernist Constructs’ went on to show, she opted, in her painting, to follow a pathway that led through figuration towards the near-abstraction of ‘Girl and Flowers (Orange and Purple)’ of 1959, and ‘Flower Girl (Blue)’ of 1960, and to the explorations of pure abstract form and colour that succeeded them; the Towner show had two of the last of these, ‘Moon Shadow’ and ‘Unripe and Ripe’, both from 1983, small, suggestive compositions of circles, crescents and voids on raw canvas.

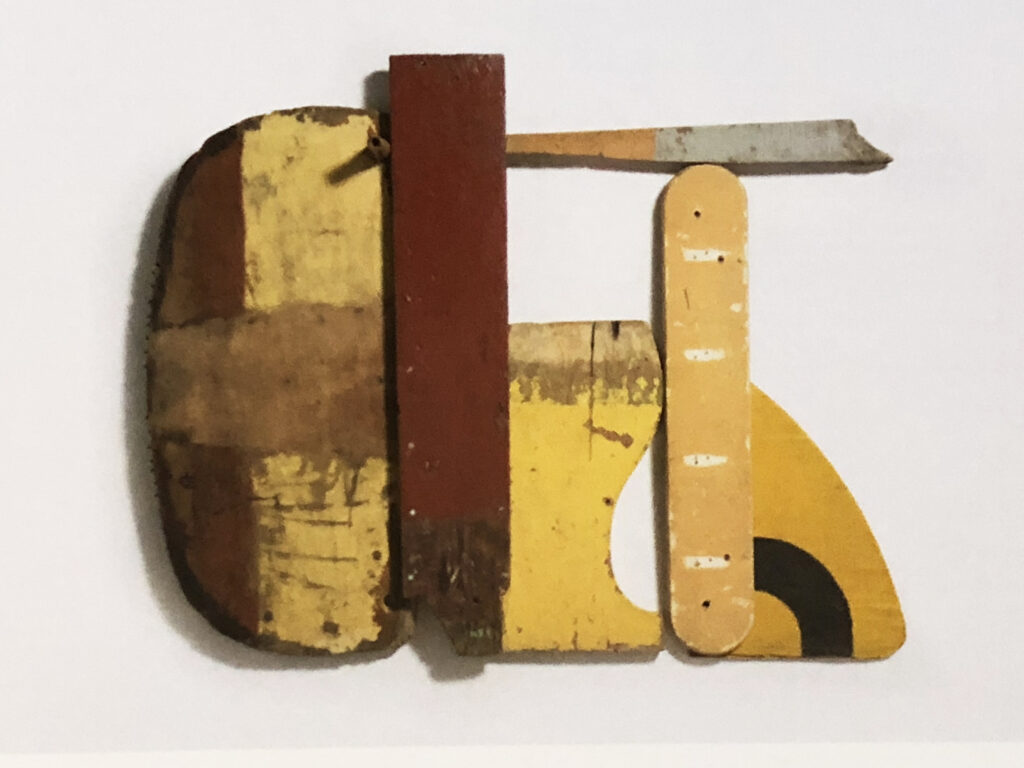

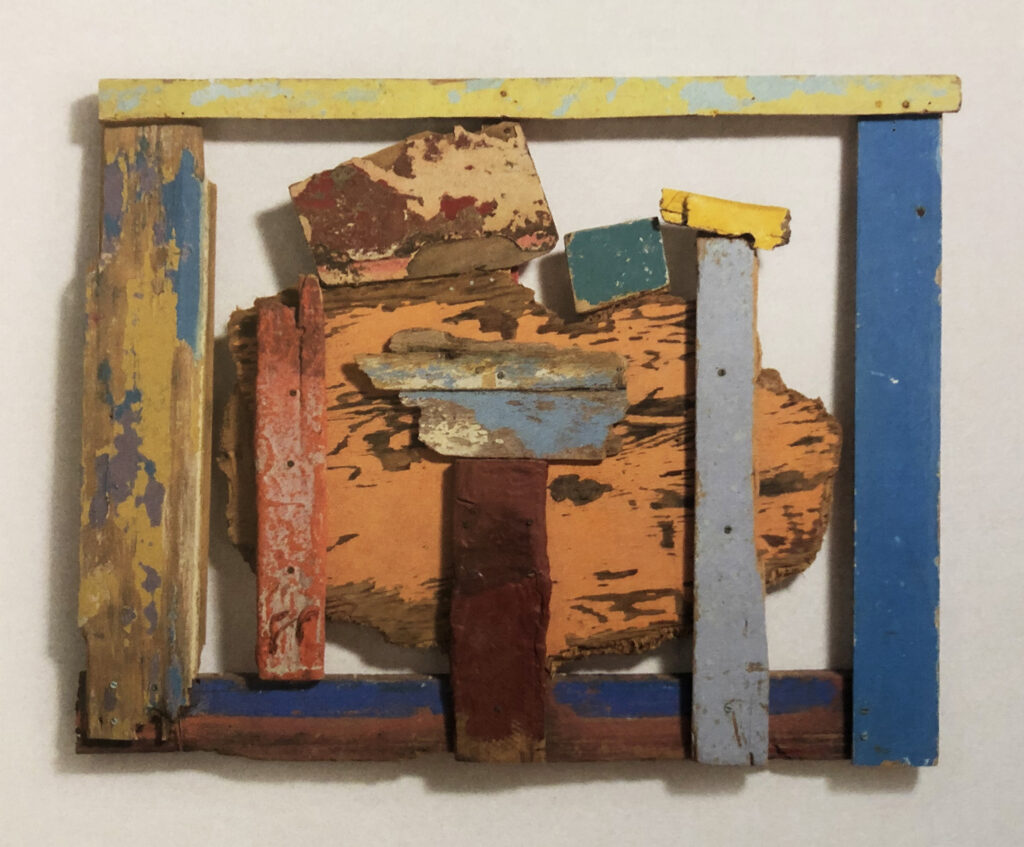

Her work in relief began in earnest in the 1970s, in the years after she and Davison had moved to Southwold, where the beach yielded a surfeit of distinctive forms in driftwood for her to use. The early, unpainted reliefs are polite and restrained; the colour is mostly the bleached natural hues of wood, creating delicate tonal essays in brown, beige and sandy ochres, and staying within the format of the rectangle. They have the feel of Nicholson’s work, without showing overt influence. As she begins to find her own voice, the reticence enforced by English politesse is abandoned, lessons learned during her time in France come to the fore, and the growing boldness of the work has something of Schwitters, of Gabo, and even, perhaps, of the radical colour exercises taught by Harry Thubron and Alan Green at Leeds School of Art in the 1960s.

The driftwood and marshwood that Mellis found and took back to her studio were mostly painted, with the colour flaking off, bleached by the sun or scoured by the sea. They would have needed cleaning and sanding, but with few exceptions (all of them hard to spot amongst the work in the Towner) no paint was added as she moved them around.

Mellis would have used the floor or a table top to arrange her pieces of found wood, and would only have been able to view the work at eye level on the wall once its parts were joined together. Nothing surprising here: many modernist painters have worked in this way (Pollock being the obvious example) and the development of fast-drying acrylic paints has shortened the journey from floor to wall to a matter of hours. John McLean used to tack his canvas onto a thin plywood board, painting it on the floor before setting it against the wall, turning it to see it in every orientation.

She seems to have fully relaxed her grip in the series of works that includes ‘Icon’ of 1986, and ‘The Hermit’ of 1989, in which bottle shapes have been cut from boards and placed within an enclosed space. Of these, ‘Resurrection’ of 1985 is the most remarkable, with its pieces placed on little shelves, and the work’s base becoming a shelf for the whole when on the wall. This improvisational, free play with the raw ingredients of her reliefs situates her squarely within the modernist tradition, with its emphasis on a willingness to let the materials deliver, and on discovery of the work’s form through protracted, instinctual adjustment and decision-making; a tradition celebrated in Kenneth Noland’s brief tribute to David Smith, published in ‘Art International’ after the sculptor’s death: ‘He knew more about how to go about working than any artist I know or have known.’ There is film footage of Smith in his metal-toecapped boots, kicking pieces of steel on his studio floor, contemplating and then welding them together, before hauling the assemblage up onto a gantry to continue working on it. It shows the way an abstract sculpture could- and, arguably, should- be made. Caro, too, was unquestionably inspired by found objects, and like Smith, was prepared to pay in sweat to transform these first moves into fully resolved sculpture; and Motherwell maintained that his series of paintings, ‘Elegy to the Spanish Republic’, resulted, in part, from adopting the tactic used by the Dadaists and Surrealists, of drawing blindfolded; with the key difference that he continued to work with his first marks, rather than simply serve up the act or gesture as complete in itself. For the Abstract Expressionists, these sorts of experiments were means, not ends; a means by which to surprise themselves, and to circumvent the tendency to rely on ‘taste’ or previous experience of ‘good’ art.

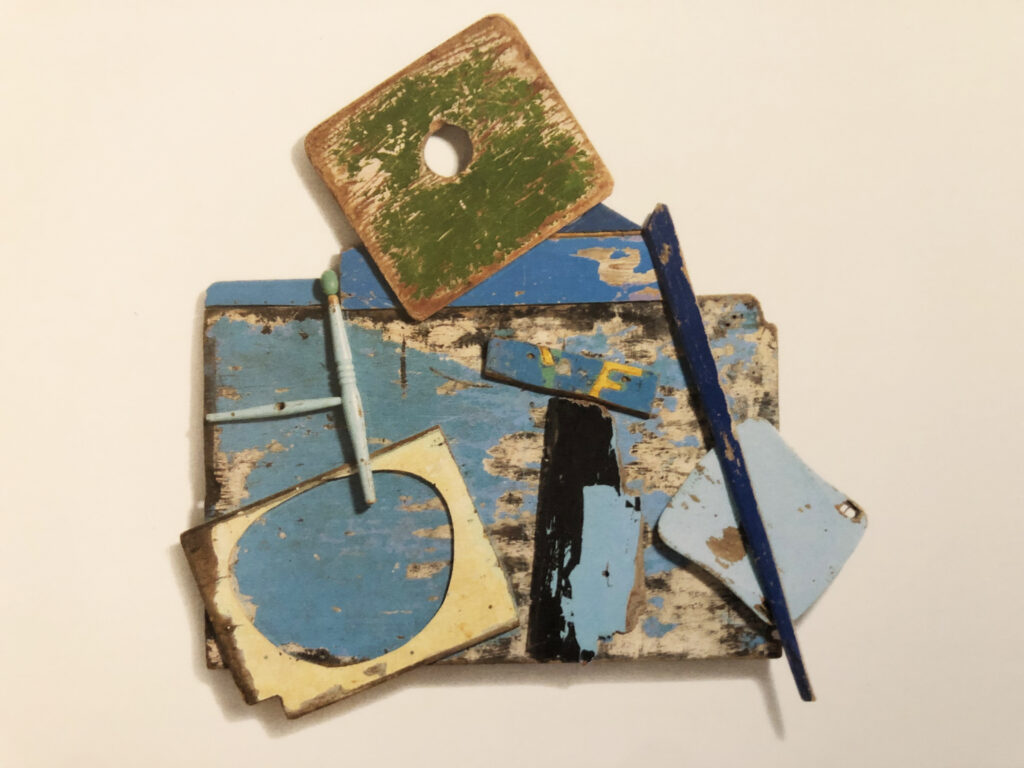

This is how Mellis’s ‘Heap’ of 1991 has found its form, through just this kind of coming-together of chance and hard-won choices: its title was inspired by its first state, a random accumulation of scraps and sticks of driftwood on her studio floor; but what a subtle and beautiful peripheral contour she has worked to find, binding it all together visually. ‘Fisherman’ from 1990-91, ‘Ribbed’ and ‘Bogman’ from 1990, are all masterpieces; in these, it is colour that drives her, and colour where she finds mastery. ‘F’ from 1997, despite the over-large green rectangle at its top (a rare example of Mellis succumbing to what I have described elsewhere as the ‘Grand Manner’ in sculpture, and a problem that would disappear if the work had been inverted) is presented as the show’s centrepiece, and rightly so: it has that level of gravitas.

The Towner show was not without faults: Mellis’s work is visually very active, and needed room to breathe. The reliefs should have had double the space they were given: they were fighting each other in a manner that put one in mind of the appalling hang of the Hoyland-curated Hans Hofmann show at Tate in 1986.

And could the work itself be faulted? Driftwood sculpture has become, in many eyes, a sweet, safe pastime for hobbyists, easy to achieve, with a certain sort of tasteful prettiness as guaranteed outcome; ‘Beachcomber art!’ is invariably used as a put-down. Margaret Mellis deserves far better than to share the blame for work made in her chosen medium by any number of lesser talents; she was an inspired artist with robust taste, a remarkable woman, who, in her seventies, created a body of work that merits permanent display in our major museums.