Since setting up Instantloveland in 2018, myself and co-editor Matt Dennis have been aware that most of the essays that we have hosted on the site have a strong historical bent. We welcome this, of course: as the mantra in our mission statement explains, ‘by both reaching back into its past and considering its potential futures, Instantloveland will explore how abstract art has continued to interact with broader aspects of social and cultural change, whether they be aesthetic, political, philosophical, and/or technological.’

So that’s all clear then? Actually, no, it isn’t; because use of the term ‘abstract art’ presents all kinds of difficulties. What do we even think we mean by ‘abstract’? Having tried, in my last essay, to explore the meaning(s) of American abstraction of the 1950s in relation to what that same art might mean in the global context of the 1990s, I’ve been left wondering whether it should be seen as a purely historical phenomenon, a set of guiding principles for the production of paintings and sculpture that the onward movement of the culture has rendered redundant; or, conceivably, whether abstraction remains viable; in which case, have its ‘guiding principles’ remained constant, or have they changed in order to meet the challenges of making art in the 21st century? Which of the theories that grew up around abstract art still resonate with contemporary practitioners, and which have been consigned (for the time being, at least) to the recycling bin of history?

And so, we thought it vital, after a run of essays dealing with abstract art of the past, to explore what abstract art might mean to artists working now. I have begun a series of ‘conversations’ woven from emails, text messages, and (Covid permitting) face-to-face encounters in studios with artists who, as far as I can see, are working with certain aspects of abstraction. In each case, I ask the artist about their first encounter as a viewer with abstract art, and this acts as a prompt for dialogue around questions of how abstract art is constituted; this, in turn, leads into a consideration of the artist’s work, its methods and preoccupations, and its relationship to the history and practice of abstraction. Hopefully, as this format for discussion develops and more artists take part, our blurry picture of contemporary abstraction might come into sharper focus; and at the very least, the questions outlined above will be aired and shared between us all.

Peter Lamb was born in the UK in 1973. He studied at Camberwell College of Arts from 1993-1996. He lives and works in London. His work combines painting, photography and print media in an equal three-way collaboration that explores their respective interactions, the traits of each medium submerging and surfacing within the practice of the others. Over the last 25 years, Lamb has exhibited extensively both nationally and internationally, with recent exhibitions in Iceland, the USA and The Netherlands.

JB: Can you remember the first abstract painting to make a real impression on you?

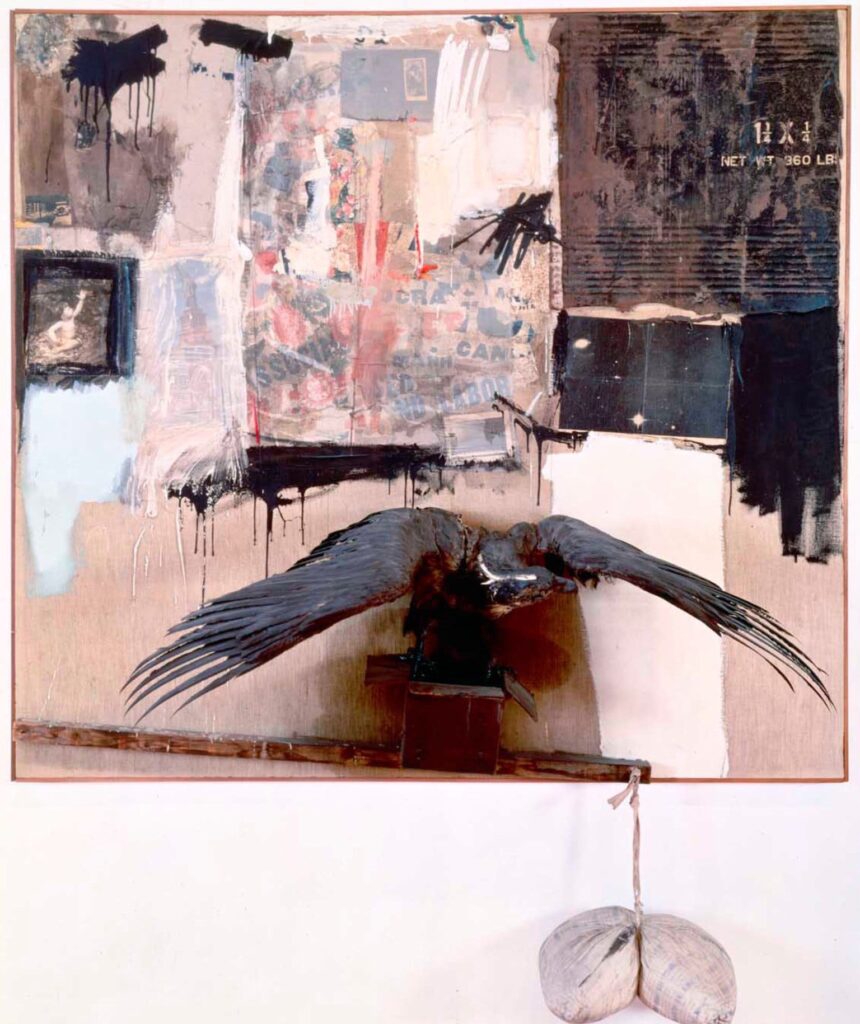

PL: I think Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘Canyon’ helped me to be more open to the wider possibilities of painting. I loved the eagle’s wings in their attempted flight away from the painterly surface and flattened cardboard boxes. The pillows look like a dead weight holding it all back.

JB: In what ways do you see ‘Canyon’ as an abstract painting, given that it contains both representation (photographs) and literal presentation (the stuffed eagle and pillow)? What does this tell us about your interpretation of the term ‘abstract’?

PL: If abstract art is about attempting to distance itself from objective references, then ‘Canyon’ seems to wrestle with that issue. It’s a four-ball juggling act, comprised of painting, collage, photography and sculpture, in which the painted marks erase the representational (photographs) or, perhaps, re-prime the surface of the painting. The literal is present in the sculptural form of the pillow and the eagle; yet they are both referential, the former suggesting two lumbering, weighty testicles, the latter stretching outward, evoking the idea of attempted flight (escape) away from the painting. The painting ignites and moves front to back, up and down, left to right all at once, gnawing at itself and abstracting as we watch.

‘Abstraction’, for me, contains within it the gestation of the figurative, somehow earned and not simply conjured up halfway through. Ideally, there is a sense of where the abstract comes from and where it might be heading. Abstraction offers openness, like working in the gap between the extreme points of outstretched arms, or, in this instance, the outstretched wings of Rauschenberg’s eagle!

JB: Collage seems to be central to your way of painting. You are a painter, yet you work with digital photography, often introducing images at varying sizes within one piece of work. How has your relationship with collage and digital reproduction developed?

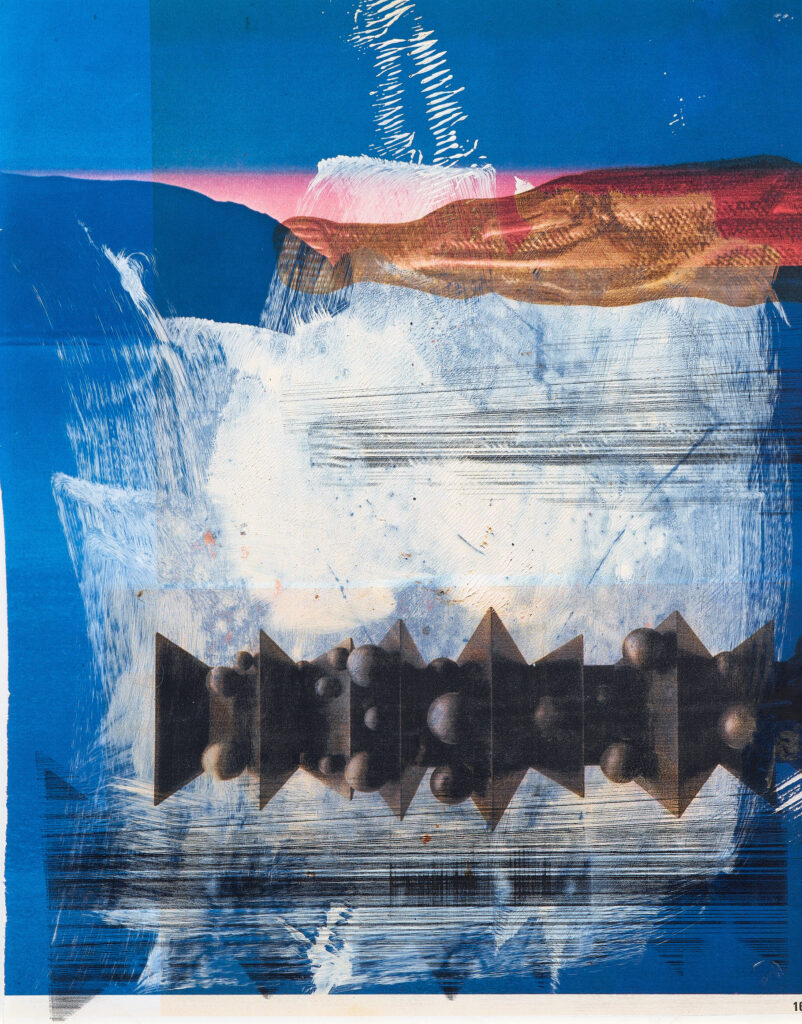

PL: I started using photography around 2008, in order to be able to quickly create new painterly grounds by photographing the peripheral elements of a painting attempt – a floor, a wall and studio detritus. These elements yield images that resemble abstract paintings; they are then painted on or collaged over before being re-photographed for further digital reproduction, often at a size that disorientates. This process is repeated and repeated to the point where the sense of the original figurative image is lost: we are wandering through an endless hall of mirrors.

JB: You say that, for you, abstraction somehow contains the figurative within it. Your work is full of abstract tropes, such as the grid, or images of splattered paint and globules of pigment; yet it often also references objects and landscape. Do you see your work as both abstract and figurative?

PL: To an extent, I think that’s true. The studio detritus would be the starting point, the figurative aspect; from there, it is broken down, in other words, abstracted, through a series of operations: overpainting, photography, and printing, the latter two introducing extreme changes of scale. Like two pistons in an engine, the idea is to push and pull, colliding the opposing mediums together to such an extent that something else can take place. Hopefully, at its best, the work exceeds the sum of its parts, igniting and combusting like an engine. When this happens, I feel a momentum building, and I can orchestrate the work better.

JB: The layering of imagery seems central to your process.

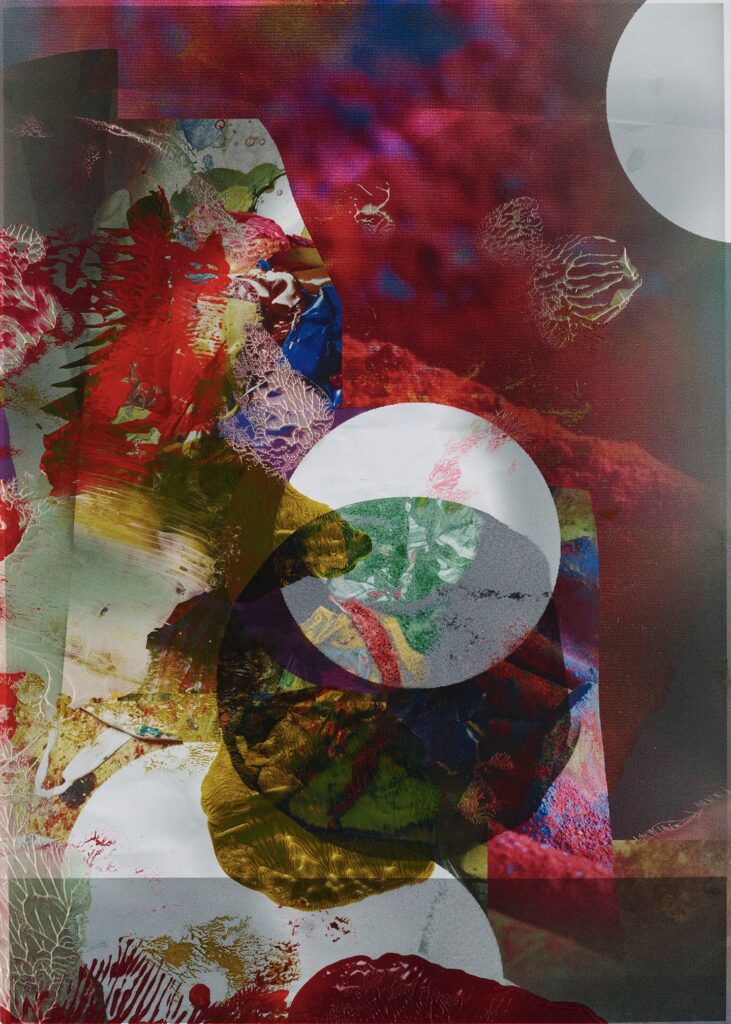

PL: I would agree. My painting, printing and photography have been fused together to the point where I now have a vast collection of super-high-res images that I can deploy as new painting grounds. Embedded within the images are layers and traces that reference previous paintings and processes, hopefully giving an insight into where the new painting has come from, and where it is going.

JB: I think your paintings have an odd kind of lyricism about them; yours is not an abstract art one might associate with lyrical abstraction as such, in the sense of finding some kind of equivalent to nature, but, rather, it evokes a lyricism born of digital manipulation. What do I mean by that? To return to ‘Canyon’ for a moment: in the 1960s, Leo Steinberg argued that artists looked to culture, rather than nature, for inspiration; for Steinberg, Rauschenberg’s work exemplified this shift. Arguably, with ‘Canyon’, Rauschenberg is alluding to the grandeur of Abstract Expressionism, whilst satirising the machismo that drove the quest for that grandeur; and doing so by sifting through culture, a culture coming to him in the form of found images and objects- including, notably, images from his own family life, such as photographs of his young son, and of the family car of his childhood. ‘Canyon’s images poke fun at the aggressive masculinity of the New York School through their sly allusions to the myth of Ganymede, the beautiful boy that lustful Zeus, transformed into an eagle, snatched away to Mount Olympus to keep as his personal wine steward…for you, the pillow suggests ‘weighty testicles’, but might they not also be fulsome buttocks? Rembrandt’s ‘Ganymede in the Claws of the Eagle Zeus’ of 1635, (referenced more overtly in another Rauschenberg ‘Combine’) points us towards this reading.

Would you agree that your work also harbours this allusive lyricism, coming out of arrangements, defacements and layering of found images that in a sense are cultural artefacts?

PL: Yes, a lyricism for sure, one that I have been intuitively drawn to. I think the cavernous American landscape, culturally and physically, is captured in ‘Canyon’. I have always liked artists who draw from a vast universal memory bank of source material; Keith Tyson, for example, or Helen Marten.

I always had the energy to add new acquisitions to my image bank; too much energy, perhaps, as someone once described me as a live electrical wire, flailing around! I didn’t mind; at least that meant I had energy; I just needed to learn how to direct it. Through my student days, and long into my career, I catalogued all these images in an inventory which I wore, as it were, like an increasingly heavy jacket. I became a competent picture maker, I think; but over time the images started to decay, not so much physically as in my thinking. That’s when I first became interested in trying to retrieve the remnants and find ways to reignite them. Under that accumulated weight of photographs, collages and paintings there had to be a collapse; and in that collapse, unexpected and new things would appear.

I do think events in my life over the last four years – with Covid restrictions thrown in for good measure- have been pivotal to how I’m now thinking about and processing all the information and source material I have acquired over the years; and about how I want to stutter forward. I would like to try to say more about this, because there’s something there to be gleaned; but I want to avoid the urge to go all (art) therapy on you!

JB: Fair enough. For me, one way in to your work might be via this notion of yours that you referred to earlier, of ‘re-priming the surface of the painting’. I say this because I don’t see yours as a representational or narrative-driven art but, rather, as an abstract art founded or formed in representations. Am I on to something here or not?

PL: Yes, the representations are transient and malleable, with one action perpetually informing the next, so there is an endless abstraction or fracturing of previous images, thoughts and ideas; by being willing to undo and re-prime, or wipe away, the surface, interesting traces remain. That doesn’t mean to say it’s a single process with a defined end point; because things get dropped, returned to, picked up and added as new images, all in a state of motion. I think to be overtly representational or preoccupied with narrative is for me too fixed an outcome; it’s too determined, or too much an admission that you ‘know’ something, and that’s boring for me as I want to keep looking. Lately, I’ve become more interested in delving into the painterly microcosms, the digitally-enlarged macrocosms, and ‘off-topic’ tributaries that I find in the work.

The boundaries shift in response to the push-and-pull of self-regulation and personal wishes – constriction/release, collapse/renewal. For all this material to be navigated, a necessary condensing must take place; in much the same way that the world around us must be condensed. We reduce the world into manageable low-res jpegs, if you like; that’s how our brains work, that’s how we see the world around us. What happens, though, if one tries to work oppositionally with these fleeting apparitions, and avoid a singular, predetermined process of seeing by continually dropping things, going back to pick them up, or continually feeding in unexpected images in a state of motion or inertia? I’m taking one step back and two steps forward, adding and subtracting as I come and go. It seems more interesting, and more truthful, to sift through images this way, rather than just responding in a static, singular way. It’s an abstract art formed in moveable representations.

JB: Your phrase, ‘A necessary condensing’ is intriguing. What excited you about ‘Canyon’ was the way in which it takes painting towards the sculptural, the photographic, the painterly, the collagic, the autobiographical, all at once; can we understand your paintings as ‘necessary condensings’ into what we might call ‘digitised palimpsests’? They register the imprint of numerous images, in a manner reminiscent of Freud’s description of how memory images become layered within the unconscious. I’m thinking of his short essay ‘A Note Upon the ‘Mystic Writing-Pad’’ in which he describes the child’s toy comprised of a plastic screen, atop a piece of waxed paper, atop a resin-covered surface (we know it better as an ‘Etch-a-Sketch’). The pressure of the stylus is transmitted through the plastic to the waxed paper, leaving a dark trace on its underside where the resin has adhered; the marks disappear once plastic and paper layers are lifted, but the drawing remains as an indentation in the resin layer, detectable when held at an angle to the light. For Freud, this indentation served as the perfect metaphor; but perhaps Thomas De Quincey offers the most eloquent evocation of these numerous and subtle mental processes:

‘Everlasting layers of ideas, images and feelings, have fallen upon your brain softly as light. Each succession has seemed to bury all that went before. And yet in reality not one has been extinguished.’1From ‘The Palimpsest of the Human Brain. First published in Blackwood’s Magazine in 1845. This essay became part of ‘Suspiria de Profundis’, a collection left unfinished at the time of De Quincey’s death in 1859.

PL: I think ‘palimpsest’ is a lovely way to look at it, as the condensed images are retained fully in my mind and not buried below my immediate consciousness. I want to keep the images recognisable to me and near at hand, ready to be used. That said, inevitably some ‘ideas, images and feelings’ from that seeping-in of information sink to a level deeper than my conscious mind can retrieve, perhaps reappearing as veiled apparitions somewhere down the line.

JB: It’s a wonderful phrase, ‘fallen upon your brain as softly as light’. We consume so many more images now, so many more than in De Quincy’s time, or Rauschenberg’s, for that matter! I get a similar feeling from your work, especially some of these most recent inkjet prints; there’s a sense of all this delicate melding and tangling of images, from which a new and singular abstract image comes into being- falling ‘softly as light.’ De Quincey’s phrase feels so prescient because of our new-found relations with the screen; a new intimacy has been created between light-emitting pixels, like glittering jewels, and our fascinated eyes, hungry minds and desiring bodies.

PL: ‘Softly as light’ or a calm intake of breath, even. Again, I see things like an internal engine where you have the dichotomy of one action coupled with another, simultaneously. You could choose to receive information slowly, softly and elegantly like ‘glittering jewels’ and filter this information through more machine-like and practical processes, such as digital media. This process can also be reversed.

JB: Not only have you collected images of painterly surfaces- canvases, studio floors and close-ups of coagulations of paint- but I’m also intrigued by these other images too; especially the ones of objects, buildings, places and landscapes. How and why have they found their way into these latest inkjets works? How do these images relate to your ‘painterly microcosms and off-topic tributaries’?

PL: I think, as you mentioned, there is a continual melding of new and singular abstract images creating an endless supply of new grounds to work from. I should say I want to fall further into the painterly microcosms of this process, where images seem to evaporate and disappear, and it becomes increasingly challenging to hold on to them. The ‘off-topic tributaries’ in the everyday images from book pages, or my own photos, that offer an opposing set of images to the pixelated and abstracted painting marks of my usual practice, provide an alternative anchoring point in that they are referencing something figurative and instantly recognisable, such as architecture or landscape. The merging and colliding of the painting process with architectural images evokes a demolition or building site; and in the landscape images, the painterly interventions suggest an excavation of earth and soil.