Matthew Maxwell: ‘Mandarin Meets Machine: Philip Guston’s Diffusion Model

‘Philip Guston Now’, at London’s Tate Modern, was originally due to open in June 2020. But a hoo-hah around the hooded Ku Klux Klan figures that feature in his later work caused its postponement until… well, now. And while a handful of years may not mean much in the great panoply of time, a lot has happened in between: a global pandemic, a European war, an attempted coup in the US, civilian slaughter in the ‘Holy’ Land, accelerating climate change, amongst other frontpage events.

But it is the arrival of a damburst of open-access AI apps, and their implications for creativity, that I will discuss here. I want to consider how two very different creative entities compare: Philip Guston, and Text-to-Image Generative AI. One a flesh-and-blood, sentient organism labouring to make sense of the world using paint, brush and canvas; the other a series of emotionless decision-making protocols flowing across the semantic chaos of the internet. Specifically, I will examine the principle of Diffusion and how it might suggest an affinity between the two.

Comparing analogue Guston to digital AI might seem an obtuse experiment. But the debate around organic and computational creativity is happening right now, which makes the title of the Guston retrospective all the more provocative. It asserts a contemporary relevance, or at least implies the question: ‘What can these paintings mean to us now?’ One thing they might offer, I suggest, is a model of creative method that might help us better understand Creative Artificial Intelligence. Which could be very useful. Finding modes of interaction with this accelerating presence in our daily lives is too important to be left to engineers, politicians, capitalists or zealots. The artists need to get involved too. For that to happen, we will need to find a common language to converse with. Diffusion may be one.

The Stumblebum Mandarin1Paraphrasing Hilton Kramer, New York Times, October 25th, 1970

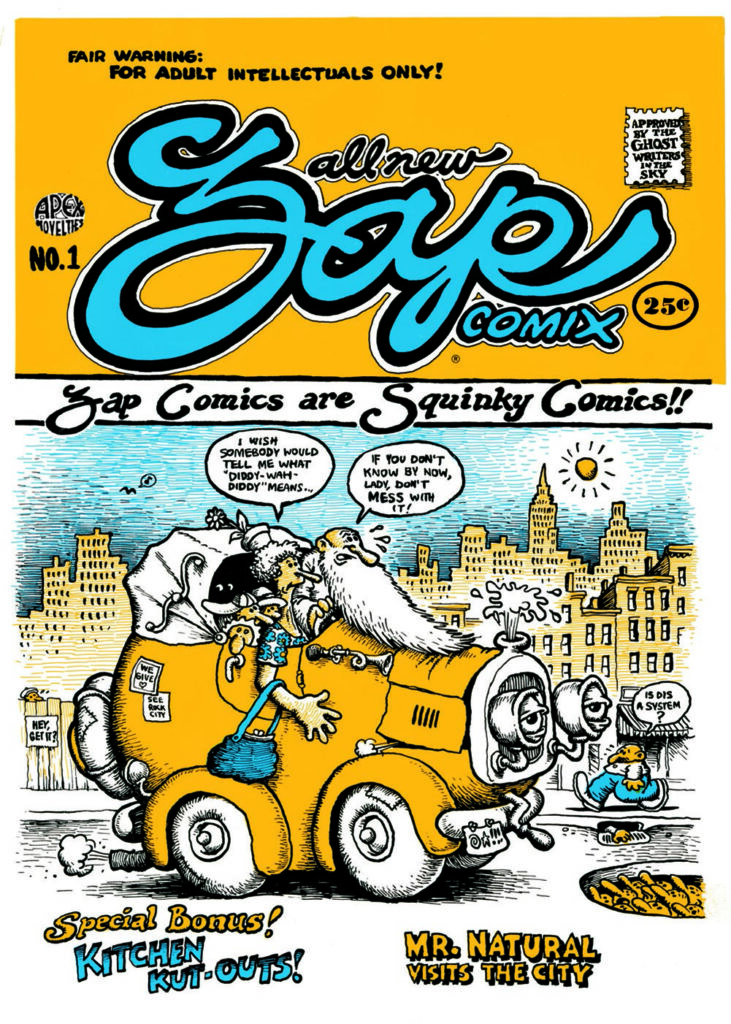

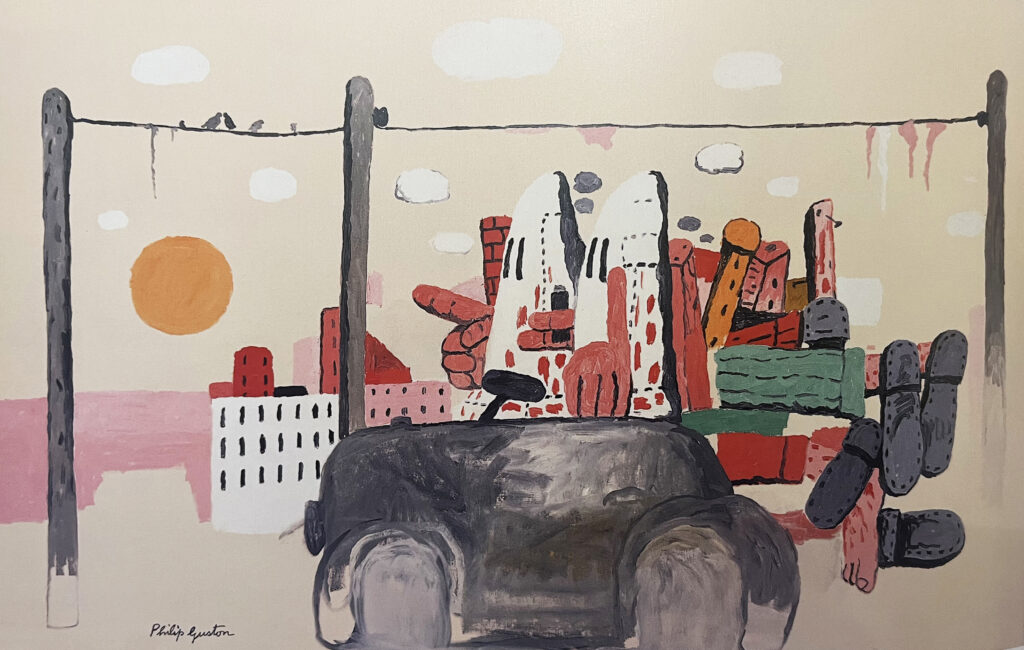

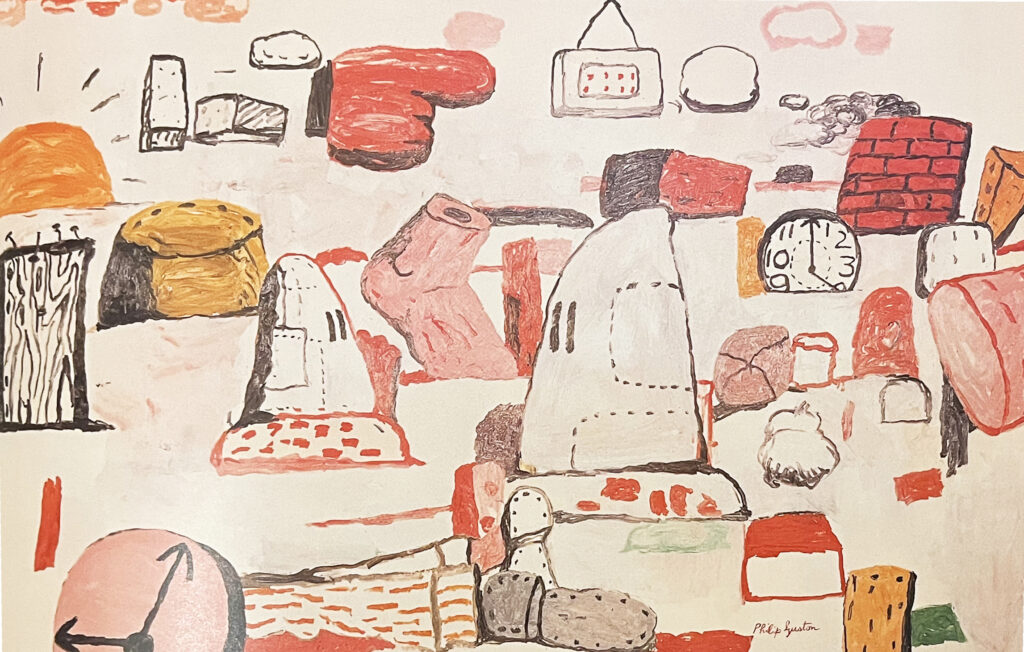

If we’re going to position this thought experiment anywhere, Philip Guston seems as good a place as any to start. It’s hard to imagine a less machine-made artefact than one of his canvasses. They are almost gratuitously physical: seemingly hewn out of the canvas with visibly, tangibly, laborious effort. In reproduction they’re powerful – when I first saw them in magazines in the 1980s they left an indelible mark on my own development as an artist. Their childish aping of the motifs 2https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Underground_comix and crude humour of West Coast undergound comics was startling and exciting.

The brashness, the bravura, the reductive simplicity of the mark-making, the childish glee in the fatness of the paint: all of these add to the impact of the paintings of the 1960s and 70s that followed the abstract works that secured his reputation. They engage. They stare back. Perhaps their apparent cartoonish contempt for seriousness, and for their own disturbing relevance to the world beyond the canvas edge, worried the Smithsonian into delaying the show.

AI image making, by contrast, creates quiet, calculated things. Pose it a problem, digital neurons pop and fizzle and…it’s done. But quite what is done is less easy to explain. There is no matter involved; no material has been rearranged, only energy. Pixels have been summoned and configured. No paint has been spilled. Painting is physical and organic; this is computational and virtual. The two seem irreconcilably different. Guston himself certainly took that view: ‘Painting and sculpture are very archaic forms. It’s the only thing left in our industrial society where an individual alone can make something with not just his own hands, but brains, imagination, heart maybe.‘3Sichel, K., Guston (1994). ‘Philip Guston, 1975-1980: Private and Public Battles’, University of Washington Press

By contrast, AI represents perhaps the current apogee of automation; a creative process that requires a form of brain, but certainly no hands, or imagination, or heart. Nevertheless, an exhibition label for Guston’s ‘The Line’ of 1978 suggested a possible link: ‘Guston recalled something John Cage once said to him: “When you start working, everybody is in your studio – the past, your friends, your enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas… But as you continue working, they start leaving, one by one, and you are let completely alone. Then, if you are lucky, even you leave.”’4ibid.

It occurred to me, on reading this label, that the process Cage describes (and Guston, presumably, employed) has affinities with that used by text-to-image AI agents such as DALL-E and Midjourney. Both the painter and the AI are using a process of ‘Diffusion’.

Diffusion and Reverse Diffusion

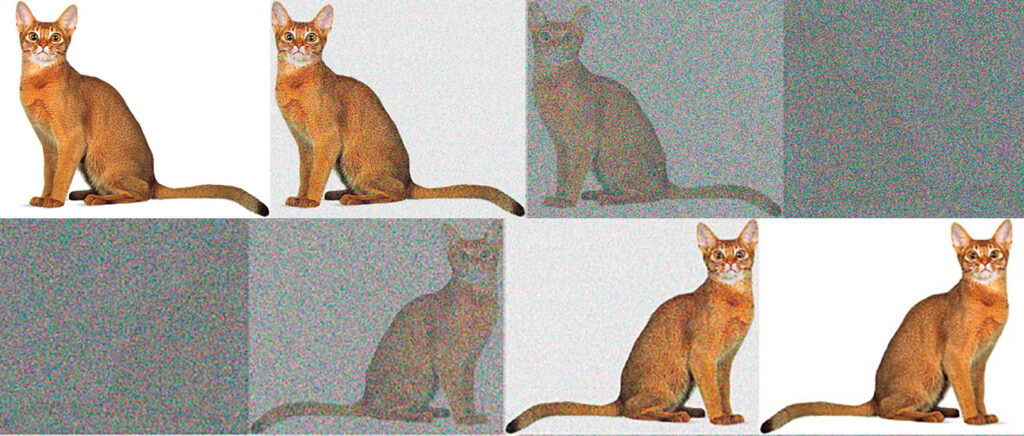

In Biology, Diffusion is the movement of molecules from high concentration to a lower concentration. It’s equivalent in the arts is the removal of extraneous material or information that does not represent the idea: a reduction to essence. Generative artificial intelligence apps use Diffusion models to generate novel images based on the data they have been trained on. Diffusion models are generative: built to generate fresh data similar to the data on which they are trained. They do it by destroying successive additions of Gaussian noise –visual white noise in the form of randomised pixels – then recovering the data by reversing this noising process to reveal a new image.

Imagine dropping red ink into a glass of water. Initially, it will be concentrated around where it entered the water.

Over time it will spread out in an even distribution resulting in a glass of pink-ish water. Reversing this process would gather all the ink molecules back into one coalesced concentration – like reversing the video – bringing it back to its original state. Common sense tells us this is not possible in the real world – how could we possibly calculate the speed and trajectory of every molecule accurately enough to be able to play it backwards? But if we’re not in a physical world, but a computational or mathematical one, even though the calculations might be daunting it would be theoretically possible to create a kind of musical score, recording the diffusion process. By playing it backwards we would arrive back at the moment the ink hits the water.

AI agents have been trained by adding not ink to water, but images to noise. A picture of, let’s say, a cat, is ‘diffused’ by hitting it with successive volleys of noise. But because the ‘molecules’ being diffused are actually pixels, each of which can identified numerically, the process of obliteration to chaos can be logged. It may be stupendously complex, but it’s possible to reconstruct the cat image. All that’s required is to run the program backwards. Out of chaos comes cat.

The more often they do it, the more data and detail and nuance they can produce. If, for example, we ask AI to generate a picture of that cat sitting on a toadstool wearing a hat, an AI diffusion model will look at the chaos, then remove everything which doesn’t resemble a cat sitting on a toadstool wearing a hat. Since it’s been trained on billions of cat, hat, and fungi pictures, it has a pretty good chance of arriving at something that at least resembles the original ‘prompt’.

It does this through mathematical calculations too specialist for me to fully grasp, let alone explain. But you can learn a lot more about Markov chains and ‘latent variables with the same dimensionality’ here:5https://www.assemblyai.com/blog/diffusion-models-for-machine-learning-introduction/

Surprise Surprise

Using mathematical calculations to generate creative imagery suggests the outcomes will be (as mathematics promises) predictable and repeatable. But this is not the case. AI, with its almost limitless vocabulary and speed of recall can surprise. The criteria it uses to determine what to include or exclude are massively complex, move at great speed and change continuously as it learns more and more alternative ways to destroy and reconstruct an ever-increasing volume of images. As Guston explained to Cage vis à vis his painting, when AI starts working, ‘everybody is in [the] studio’. AI’s studio is bursting with billions of images gleaned from the internet. It can consider the utility of ‘the past… friends… enemies… the art world… your own ideas’ at speeds that human artists cannot match. A kind of computational Shiva – both destroyer and creator of worlds – it breaks and rebuilds at speeds no biological entity, limited by the physical constraints of chemistry, can ever hope to equal.

This process of elimination and reconstruction is not new. As Sherlock Holmes explained, ‘Once you have eliminated the impossible, what remains, no matter how unlikely, must be the truth.’6Conan Doyle, A., ‘The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes’, 1927And it’s a common practice in the arts; the most obvious examples being minimalist works: those of Dan Flavin, Agnes Martin, Kasimir Malevich, Donald Judd et al., from which all extraneous information has been removed. At first appearance, Guston’s later paintings don’t appear to fit this mold – they’re aggressively organic: busy and brut. But it’s not hard to see how Cage’s observation applies. There are no passengers on a Guston canvas. Every mark has a purpose. Every dribble a duty. There are very few elements, but they’re repeatedly explored. Every other thing has left, ‘one by one’.

On one wall at the Tate, Guston’s lexicon is arranged as it hung in his studio. It looks like a typewriter keyboard; each key bears a basic unit of his visual language: a shoe, a bottle, a leg, a klansman. Each icon represents an individual letter that can generate an infinite variety of visual sentences. There are no superfluous elements. Everything else has left. With them, Guston was able to cut through the political and personal ‘noise’ that surrounded him through the sixties and seventies; the notorious hooded figures of the Klansmen being a good example. Too good, perhaps, for the delicate sensibilities of our current age, but a very real and active presence in Guston’s mind.

Guston and the Klan

The artist ultimately known as Guston was born Phillip Goldstein in 1913, the child of Russian Jewish immigrants who had fled the pogroms in what is now Ukraine. The Ku Klux Klan were active across California in the 1920s and 1930s, and Goldstein became Guston in 1935, as a rising tide of antisemitism made name change a prudent professional gambit. 30 years later, with the Vietnam war and the civil rights movement provoking violence and hatred across the country, the gentle ways of abstract expressionism, with its formal and theoretical basis, seemed to lose meaning for him. The complex webs of mark and gesture, depth and rhythm of his earlier work began, perhaps, to seem more and more like the noise that AI disassembles to find images. At some point, as he stared into this messy vortex, a reverse diffusion process started: Guston laboriously removing everything that didn’t resemble the image prompt in his imagination, scraping away the chaos to reveal…something.

In Guston’s ‘Painting No. 6’ of 1951, ‘something’ is emerging. Faintly, but with accelerating clarity out of the noise. In a similar fashion to the way diffusion models pull images out of the Gaussian mist, Guston’s motifs take shape almost in reverse – as if the painting is already there and all that’s needed is to clean the glass. More restoration than creation. As Michelangelo’s (probably apocryphal) quote says of his own method: ‘I created a vision of David in my mind and simply carved away everything that was not David.‘

Guston rendered meaning out of noise using a form of diffusion. In diffusion, particles disperse into an even distribution – ‘noise’. Diffusion in our own bodies allows substances to move between cells which keeps us alive. It occurs in gases and liquids;it appears to be a universal tendency in nature. It would be strange if it weren’t present in thought and creativity as well; both being natural, organic processes powered by biology and chemistry. The reverse diffusion process maps the resulting data chaos back to a simple distribution, allowing ‘the representation of meaningful features, pattern.’7https://opendatascience.com/generating-data-with-random-gaussian-noise/ In Guston’s case, from a low to a high concentration: the result: a small vocabulary with extensive meaning.

Depth of Processing

This transition in Guston’s work wasn’t happening in a vacuum. Through the fifties and sixties, psychologists (Chomsky, Neisser and others) were exploring the ‘invisible’ aspects of the human mind: language, perception, memory. Craik and Lockhart8Craik & Lockhart, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour, 1972, 11, pp671-684 argued that what determines the encoding of memory is the ‘Depth of Processing’: the degree of semantic involvement required to classify and retain a memory, as well as the emotional associations attached.9Willingham, The Thinking Animal, 2001, p174 Hooded figures, for example, carry a myriad of associative connections: social, political, historical. Subsequent studies have shown that there is a positive correlation between how vivid a memory seems and how emotional it is.10Pillemer et al., ‘Very long-term memories of the First Year in College, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition No. 14 pp709-715 Guston’s paintings of this period convey a passionate engagement with contemporary issues filtered through the algorithms of his own memories. His shoes, books, and light bulbs represent efforts to ‘get rid of art.’11Guston, P., ‘Talk at Yale Summer School of Music and Art’ (Yale Summer School of Music and Art, Norfolk, Conn., August 1972), reprinted in Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations, ed. Clark Coolidge (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 2011), p155To obliterate traditional iconology, then build it back into something of his own.

‘There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art. That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, therefore we habitually analyze its ingredients and define its limits. But painting is ‘impure’. It is the adjustment of ‘impurities’ which forces its continuity. We are image-makers and image-ridden.’12Berkson, B., ‘Philip Guston’s Poem-Pictures’ University of Michigan: Addison Gallery of American Art, p. 34

Perhaps retrieving memories of hooded figures, helped Guston make sense of a world that seemed to have learned nothing from the holocaust. The amoral ‘noise’ of the preceding decades and the turbulence of the times demanded a new vocabulary. With images to play with, Guston gained access to a much richer, more concentrated semiotic toolkit. Thousands of years of styles and examples to reference. Millions of semantic pathways connecting them. A painted mark can only ever be so different from another painted mark. But a Klansman, a shoe, and a cigarette all signify very different things, even though they’re still just various configurations of paint. Their temporary censorship in 2020 suggests they still have import today while the abstract expressionist works that preceded them, formally accomplished as they are, provoke little debate.

Destruction and Recreation

Why is this relevant? Philip Guston Now arrived, finally, at the Tate in autumn 2023 – an interesting Now. Now we are witnessing the appearance of an entity unlike any we’ve encountered before as a species – something smarter than us. Or, if not smarter exactly, certainly faster of thought, immeasurably vaster in memory capacity, and beginning to display disturbingly remarkable powers of invention and artifice. One whose agenda and impact is unclear. This is a contested territory: a province long considered uniquely Human. Finding what appears to be a methodological inflection point might indicate the possibility of others.

‘How can we bring together assumptions and goals of two very areas of human knowledge which are fundamentally different, as opposed to subordinating one to another?‘ asks Lev Manovich.13Manovich, L., ‘Computer Vision, Human Senses, and Language of Art’ https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01094-9 Organic brains lack the computational power to perform the feats of retrieval, combination and delivery that digital versions can boast. So what is our role? ‘Archaic forms’ in Guston’s words, might appear to represent a refuge from the reductive logic of algorithms and rules but it would seem they share a similar route to being.

In Hindu theology, Shiva’s role is to destroy the universe in order to re-create it. These powers of destruction and recreation destroy the illusions and imperfections of this world, paving the way for beneficial change. According to Hindu belief, this destruction is not arbitrary, but constructive. Guston addressed the imperfections of his time by reconstructing it out of the visual chaos of oily marks on canvas. AI builds pictures of our troubled world by first destroying it, then putting it back together. A process of destruction from which reconstruction can begin. A gleaning of meaning through chaos and noise. A beginning.

One thought on “Matthew Maxwell: ‘Mandarin Meets Machine: Philip Guston’s Diffusion Model”

Another wonderful instantloveland poem. I had lunch with Philip in Grace Hartigan’s garden in 1974. I attacked him for giving up abstraction. He smoked heavily, smiled and explained his two studios: the big one where he painted his beautiful evocations, and his living room couch where he doodled at night. I wish I could paint you all a picture of Baltimore in those days, with Edgar Allan Poe, William T Wiley and Billie Holiday’s ghosts wandering the streets. I was given a pistol by my landlord. Guston explained how one day he took his doodles down to the big studio, never looked back, only down. Yesterday I tended my shipping containers full of huge colourful abstractions, which are worth less than nothing today. Sadly Noam Chomsky is the only name I know from AI, for other reasons, to do with the slaughter of babies.