Epiphanies and Misdemeanours: Matt Dennis in conversation with Alan Gouk

Across six decades, Alan Gouk has kept faith with abstract painting; and in working to extend and enlarge the space of abstraction first opened up by the great pioneers of modernism, he has made, and continues to make, extraordinary paintings.

And whilst any serious consideration of his lifetime’s achievement must, like this post you are now reading, begin and end with the paintings themselves, there is so much more to be taken into account: his work as Exhibitions Officer with the British Council, that brought him into contact with pretty much everyone of importance in the art establishment of the mid-1960s; his long involvement with the teaching of abstract sculpture at the very highest level, on the Advanced Course at St Martins School of Art during the ground-breaking years for British sculpture of the 1960s and 1970s; his pivotal role amongst the artists that established, maintained and worked in the studios at the Stockwell Depot, one of the very last redoubts for a certain strain of High Modernism in painting and sculpture against the onslaught of postmodern art; and of course, the writing: running parallel to his studio practice, informed by the same instincts that have impelled him always to aim high in his own painting, looking always to identify and elucidate the reasons why the work of this painter or that sculptor succeeds or falls short. In the 1970s and 1980s, the late, lamented journal ‘Artscribe’ provided the platform for much of his finest writing; and in our turn, we have been lucky enough at Instantloveland to have had the chance to commission and publish several of Alan’s recent essays, to considerable acclaim.

‘Epiphanies and Misdemeanours’, the product of a day spent interviewing Alan in his home in Ramsgate, countless follow-up email exchanges, and a handful of ‘Zoom’ meetings, does its best to hold a steady course, and to (more or less) stay inside the thematic boundaries that he and I agreed on, and a narrative movement that (more or less) takes us from the 1960s right up to the present; but it also tries to do something somewhat at odds with those aims, by allowing, and frequently encouraging, its subject to roam digressively across the span of his long involvement with what he has called ‘the succulent life of painting’, recalling the ups and downs of his friendships with (amongst others) Caro, Hoyland and Heron, and a half-century’s worth of encounters- friendly or otherwise- with artists, critics, gallerists, and assorted hangers-on, and the consequences of same. At over twenty-two thousand words (by far our longest published post to date), an interview with an artist that dealt solely in weighty matters of abstract art-making would make for a very daunting read; whilst one that simply strung a series of art-world anecdotes together over that sort of length would very quickly start to grate. The hope is, then, that ‘Epiphanies and Misdemeanours’ justifies its word-count by striking the right sort of balance between the scholarly and the scandalous; and if it feels at certain points as if it leans too much towards the latter, well, all we can say to that is: you should see the unedited transcript.

Matt Dennis, London 2023

Early years of painting

MD: There’s a point in the late 1960s at which you’re making work on shaped canvasses- influenced, I think, by Richard Smith?

AG: That’s right. You may remember in my Instantloveland ‘Eye Opener’1https://instantloveland.com/wp/2019/03/12/1543/that I wrote about the big 1964 Calouste Gulbenkian exhibition, ‘Painting and Sculpture of a Decade’? It was a comprehensive survey of everything going on in painting, both figurative and abstract. That was a key point in my development, because up till then I’d been up in Edinburgh, at university, and I’d just come back down to London.

The show was a curatorial bombshell. It was designed by Peter and Alison Smithson, it was held in the Duveen Galleries, it was all presented on screens, and it was deeply unsatisfactory, because of the high toplighting. Anyway, the paintings I’d been admiring in books- books such as Skira’s ‘Contemporary Trends’ series, which had really good reproductions of De Kooning, Rothko, Still- I saw in the flesh for the first time. The painting I singled out for praise in my ‘Eye Opener’ was a Clyfford Still; but the show then moved on into European figurative painting, such as Renato Guttuso, and abstractionists such as Alberto Burri and Serge Poliakoff, and from there on into Pop Art- Warhol, Lichtenstein, Dine- with the message coming through strongly that this was the very latest thing; the exhibition felt like it built towards it. There was a Ken Noland in the show, and a Morris Louis, but I didn’t even notice them; they meant absolutely nothing to me at that time. And following on from this show, we had Bryan Robertson’s big survey of Jasper Johns, and then a big Rauschenberg show, at the Whitechapel; and so, for a time, I was swayed towards this kind of work. At the time, I was working at the British Council, where the walls were covered with Pop Art, and with works by the ‘Situation’ artists…

MD: But to understand your work at the time: am I right in thinking that apart from watercolour sketching in front of a landscape motif, you jumped straight into abstraction with both feet when you began painting in earnest?

AG: Yes. And I was very influenced by reproductions of work by the Abstract Expressionists. There was a period of De Kooning- when he was painting ‘Door to the River’, ‘Suburb in Havana’, ‘A Tree Grows in Naples’– all those big, brushy, landscape-inflected paintings- that influenced me, as did the work of Adolph Gottlieb.

That was my background, my beginnings in painting, before I arrived in London; when I got there, I was swamped by Pop Art, and briefly aligned myself with it…the reason I mention this is because I’m recognising that this is something that happens to young artists, they feel the need to be current, to be right up with the latest trends, the latest thing. And it can be a dangerous state of affairs.

MD: And you freely acknowledge that happened to you, at that time?

AG: Yes, it happened to me. And once I’d worked my way through those influences, the next stage was the shaped canvas, which was a huge trend during the 1960s. Apart from Stella, there was Larry Zox, and David Novros, who made multi-panel paintings; and in the UK, of course, the prime exponent was Richard Smith. I’d already been involved with him, because he’d been chosen to show at the Venice Biennale in 1966, for which I’d been Exhibitions Officer. His paintings of the time were aggressively three-dimensional, they were big boxes coming out from the wall. I didn’t care much for the Pop Art aspect- that they were derived from cigarette packets and so on- but I was interested in the bigness of the shapes.

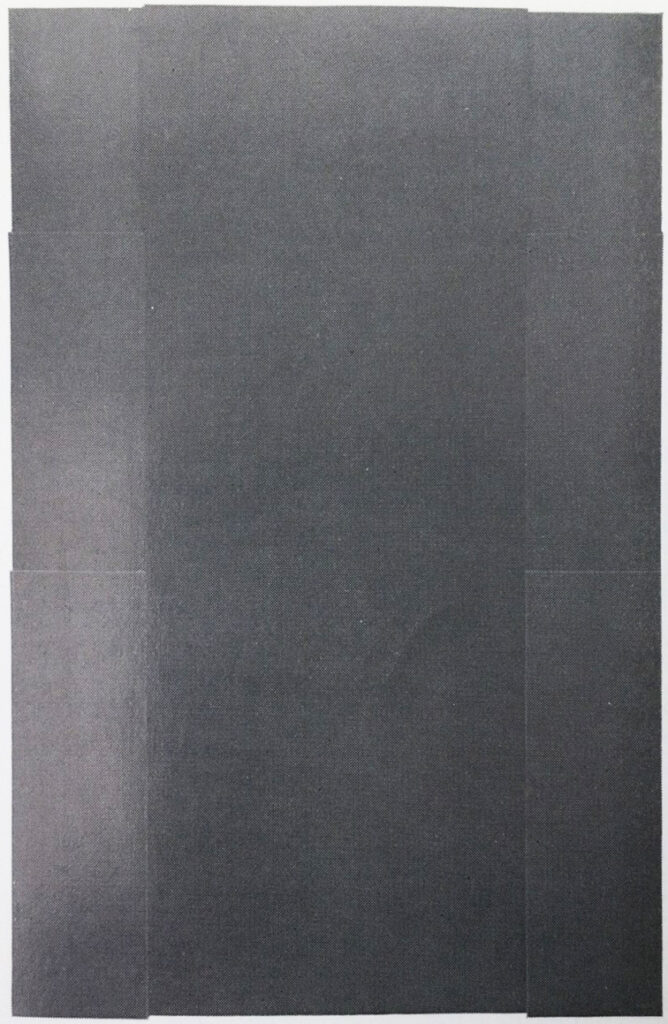

I won a prize at the 1967 John Moores exhibition for a seven-panel shaped canvas work entitled ‘Downward’. I don’t have a colour reproduction, alas; but it was almost monochromatic, painted in burnt umber, with a central panel of a slightly different colour. Symmetrical, with three steps, as it were, on either side of the central panel, almost as if a Barnett Newman had been projected into three dimensions. This sort of thing was all the rage at the time; so there I was again, being influenced by the latest trend.

MD: At what point did you see the light, so to speak, and fight free of all these influences?

AG: Since I’d won the prize at the John Moores, I was included in an exhibition at London’s Camden Arts Centre, organised by Peter Carey, who we all thought was destined to be the next big noise in Gallery directorship, a real Nick Serota- although Serota himself was still in short pants at the time, of course. For this show, I produced two big shaped canvasses, which were around seven feet high, and fifteen feet wide; and they were like big slices of cheese, projecting out about eighteen inches at the bottom, and about nine inches at the top.

MD: You built the stretchers yourself?

AG: No, I had them made; this was the way everyone operated. Richard Smith had his stretchers made, and he simply stretched the canvas over them.

One of the paintings was called ‘Cattle Catcher’ because it had this big prow on the front, like on the trains that cross the American prairies. I’d become quite friendly with Phillip King, so I was keen to hear what he thought of them; he went along, and had a look, and said: ‘Yes, they’re impressive. But it’s not really painting, is it?’ And I thought, well, I know what he means, because he was a huge fan of Matisse, and he understood that painting meant actually working with paint, for starters (laughter)…and these paintings of mine were just one-coat jobs, the stretcher had been built, the canvas had been stretched, and the paint had been applied like painting a door.

MD: Was there any modulation in the colour?

AG: Not in the colour, no, but the panels in themselves differed from one another. I did experiment with different colours and with different groupings of canvasses; but these projecting works of mine, they weren’t actually far away from what King was doing in his sculpture at around that time, and in truth I hadn’t even noticed that. There’s a sculpture of his called ‘Blue Blaze’ which consists of two or three big cubes standing in a group with some big columns, all of them painted in this same electric blue colour. And King said to me, the logical extension of what I was doing would be a move into full three-dimensionality, and that I really didn’t want to do, for a number of reasons; not least, because the shaped canvasses were so bulky and difficult to store. I couldn’t hang on to them in the end.

MD: So really, King’s criticism of these works was that they were sculptural, but not fully so? Not sculpture in the round. A hybrid, with sculptural aspirations but lacking sculptural convictions?

AG: Yes, a halfway house. In much the same way that so much of the production of what we might call the counter-culture has been a halfway house: multi-media, interdisciplinary work, installation, works that hang from the wall but spread across the floor…

In other words, I began to understand that painting has limits, and should have limits; that it is essentially a membrane, a taut surface. I recall Patrick Heron at his Tate retrospective, saying that a painting lying on the ground is not a painting: that painting is a surface at eye level, on the wall. And anything that sticks out from its surface is irrelevant. The third dimension in painting is always fictive, a result of its illusionistic properties.

MD: When exactly did you undergo this Damascene conversion to an understanding of the flatness of the canvas as indispensable to painting?

AG: In 1968 or 1969. I was working on cotton duck, laid on the floor, and I was pouring oil paint onto it, into it. I’d lay down a large sheet of cardboard, lay the painting on top of it, and soak it, in much the same way as Morris Louis or Helen Frankenthaler, but with the difference that I was using oil paint on raw cotton duck, which is technically extremely hazardous. This is why I haven’t been able to keep many of these works.

MD: The oil rots the canvas fibres, doesn’t it?

AG: Yes, but at the time I didn’t care, because I wanted the staining to go in really deep, rather like Jackson Pollock’s black paintings, in which he used enamel paints, and there’s a halo of dried oil around the marks, which isn’t pleasant. Then I’d flip the paintings over, face down, onto the cardboard to soak up surplus paint; and in some cases I’d end up working on the back of the canvas rather than the front.

Sculpture

MD: By this point, by the end of the 1960s, you’re very much involved with St Martins, of course.

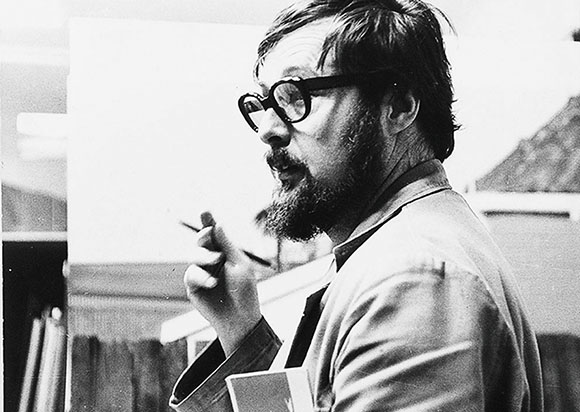

AG: I was offered a teaching job at St Martins in 1967, thanks to my friendship with Caro, King, and Isaac Witkin, who all recommended me for a post; but I’d never made a sculpture in my life, how the hell was I supposed to teach sculpture? My role was to chair the Sculpture Forums and get groups of people together and organise debates; that’s how it began for me.

MD: You’re well aware of our interview with David Evison2https://instantloveland.com/wp/2021/07/23/a-fly-on-the-ceiling-matt-dennis-in-conversation-with-david-evison/since you contributed extensively to the comment thread; and you’re aware that he describes the Forums as something akin to the Roman gladiatorial arena. According to him, people were being thrown to the lions, and you were overseeing it…

AG: I was a mediator, trying to, well, to mediate…(laughter)

MD: But David makes it sound savage.

AG: But you have to understand, the difference at that time between St Martins and any other art college was that you didn’t have a cubicle system where tutors came in and saw a student individually, and said, well now, I see that you’ve got a photograph of Elvis Presley there (laughter)…nothing like that. It was all open, communal activity; partly because of the structure of the building. The sculpture department was divided into several areas, none of which had any technology, other than a woodworking machine. Totally unlike the RCA in that respect, which had all this machinery for the cutting and bending of steel. At St Martins, you had the studios up on the top floor, where Caro used to conduct his classes; you had the Diploma Course (as it was just becoming then) in the middle floor studios, which William Tucker had been invited in by Frank Martin to run, and to give some sort of intellectual backbone to; and then you had the welding shop, for oxyacetylene and arc welding- and there I think there might have been one small machine for bending steel. Primitive stuff. And out the back of the school, you had the stone-carving area, where people like the Israeli stone carvers who’d come over specially could do that sort of thing. And above it all you had the asphalt-covered flat roofs on top of some of the studios, where you could lay out sculptures to be looked at. But all of it was really all over the place, very chaotic.

MD You were brought into this chaos to run the Forums…

AG: But I was also brought in because of my contacts within the art world. I’d been an Exhibitions Officer for three years, and I knew a great many people…

MD: But it was understood that your credentials for critiqueing sculpture were simply that you had a well-honed critical eye, rather than ‘here’s my sculpture’?

AG: Well, I had also had a hand in organising shows of sculpture, such as the ‘New Generation’ Whitechapel show, which had travelled round Europe, taking me with it…

Bear in mind that at St Martins, I was also put into the first year of the Diploma course on a two-days-a-week basis, presumably in order to learn the nuts and bolts; because all the knowledge I had of sculpture was theoretical, if you like, and aesthetic. When Frank Martin had me on trial to see what I was like, somebody brought sculptures in and he came in and listened to me talking about them.

When I was at the British Council, one of the shows I’d had to organise was a photographic touring exhibition about Henry Moore. Moore was everywhere at the British Council, he was God. It was hard to tell whether the British Council was running him, or if he was running the British Council. He was the British Council. And of course, they had great success off of that.

So, if you ask me what I knew about sculpture then, I can say that my knowledge was cumulative, I knew about Moore; and I knew all about what was thought and said about him, and then I’d got to know the ‘New Generation’ sculptors, Caro, King, Tucker, Tim Scott, and so on; I’d got to know nearly all of them personally and had toured Europe with their work, and had got into various spats over it.

I’ll describe one. In 1967 we toured the ‘New Generation’ sculpture: but to give a little context, I should explain that the Venice Biennale of the previous year had been a sort of pivot point, between the old school in British art and the new, the latter being represented by the ‘Situation’ artists and those that followed afterwards. And so it was that Bernard and Harold Cohen, Robyn Denny, Richard Smith and Anthony Caro were all chosen to be in it.

The first stop on the European tour of the ‘New Generation’ show was the Kunsthalle in Bern, in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, a place we could describe as the area’s commercial capital. Harald Szeeman was the Director of the gallery, and he was a high-flying, ambitious curator- one of the band of people I like to describe as ‘tin-pot Diaghilevs’ (laughter). (Subsequent to the episode I’m going to describe, he made his name with ‘When Attitudes Become Form’, the exhibition that showcased all manner of Arte Povera and ‘Anti-art’, in which he posited curatorship as an art form in its own right; he was the first to do that).

Anyway, shortly after the sculptures arrived, Phillip King, Isaac Witkin, David Hall (who used to make big, boxy, folded-steel white sculptures) and Derrick Woodham all flew out to Bern for the opening of the show. Come the opening night, this herd of bankers and solicitors came piling in; they’d heard what it was all supposed to be about, it was going to be Swinging London…Harald Szeeman had organised this lightshow to be projected onto the walls, images of hippies painting one another and smoking pot, and it was all being projected across the sculptures. Meanwhile, people were walking all over the sculptures, such as King’s sculpture ‘Slant’, which stacked vertically and slanted across the floor; women in high heels were trampling all over it. People were sitting on Bill Tucker’s big stacks of fibreglass cylinders, damaging one of them, so that he had to fly out to the next venue, Düsseldorf, to repair it.

Szeeman was tittering away, and I could see that King and Witkin were looking horrified, so I went over and spoke to them, and I asked them, what do you make of this? What are we going to do? And they said, this is just terrible, we want nothing to do with any of this. So I got hold of the microphone and I said, on behalf of the sculptors who are here today, I want to say that this is an atrocity, this has absolutely nothing to do with what these sculptures are about; and if you want to find out what it’s really about, I suggest you come back on another day when it’s quiet; and while you’re at it, get off the sculptures.

And Szeeman’s face went purple with rage, because he had been busily carving out a name for himself in the curating world, trying to bring together all the latest, the coolest things…the day before, he’d gone to the trouble of dragging King and myself to a showing of Kenneth Anger’s ‘Scorpio Rising’ in a dingy basement, when we’d wanted to be out in the sun exploring the town. That gives you some idea of the man.

Anyway, when we got to the next venue for the tour, the Dusseldorf Kunstverein, another Harald, Harald Behren, the Director, met me at the door as I was coming in with the sculptures and said ‘This is our exhibition, not yours.’ Word had obviously reached him. ‘You will participate in putting up the sculptures, but after that you will play no further part.’

My aversion to all forms of counterculture ‘subversion’– and to what I call the counterculture consensus as well- dates from this time and this experience.

AG: So, you were asking me how I came to know anything about sculpture…

MD: Yes. Was your experience at St Martins a case of what is now called ‘fake it till you make it’?

AG: Truthfully, I didn’t have any views about sculpture to begin with; my views developed gradually over time, as a result of seeing where all these different cross-currents were heading…

MD: So getting you in there in the first place had more to do with your mindset and your aptitude, rather than a CV as long as your arm.

AG That’s right. You see, Frank Martin was great at bringing all sorts of people in: he brought in Will Allsop, the architect, he brought in Richard Latrobe Bateman, the furniture designer…Frank was great at man-management, and he liked to stir things up; he encouraged the anti-Caro faction within St Martins, in a way, simply because he realised that students were moving in that sort of direction anyway. We had Gilbert and George, Hamish Fulton, Richard Long, all those people were there in my first year of teaching.

I wasn’t happy ‘teaching’ sculpture, in inverted commas; I never actually taught it. I commented on what people were doing. I applied for teaching jobs in painting at Liverpool and Canterbury, but thanks to the politics of the time, the successful candidates were inevitably internal appointments; they didn’t want disruptive outsiders coming in. I tried for a job in the painting school at St Martin’s, under Freddie Gore, but it went to John Edwards; despite the fact that while we were sitting waiting to be interviewed, John said to me, ‘you’re bound to get it.’

At St Martins, there had been pretty much no contact between the painting and sculpture departments, they were on different planets. The painting department resented the success that the sculptors had been enjoying, whilst they had little or nothing to show for their efforts. Freddie Gore was a very good head of department, but he didn’t have Frank Martin’s level of ambition; Frank wanted to put St Martins sculpture on the big stage, as it were.

MD: I’m assuming, since Freddie Gore was a figurative painter, that the painting department wasn’t the temple of new abstraction that the sculpture department had become?

AG: The painting department had a much bigger part-time staff than the sculpture department, many of them linked to the Royal Academy, where Freddie Gore was a major player. To be honest with you, I have very little recollection of the painting department until around 1974, when Gillian Ayres was there, as senior lecturer. She wasn’t a leading light; she was just one of the people on the staff. Shortly after that, John Edwards was appointed Head, and then Bruce Russell. Marc Vaux was also a fixture from the early 1960s. Alan Reynolds had been there since the 1950s; he’d begun as a landscape painter hailing from Suffolk, but he morphed into a radical constructivist, making white-panelled paintings.

MD: In the mold of Kenneth and Mary Martin?

AG: Not quite as bleak as that (laughter). More like Mondrian, but without the use of black, if you can imagine that. The thing about the painting department was that there was no direction to their teaching, as far as I could make out. It was like so many other art schools, where you have so many conflicting voices.

MD: My impression of the sculpture department is that it was evangelical in its mission, because by the end of the 1960s so many by then renowned sculptors were involved with it, pushing it along; but the painting department really had none of that? no corresponding sense of a dynamic, or a direction?

AG: They wanted to emulate the sculptors’ success, but they didn’t want to go about it in the same way. The painting school ran on the cubicle system. But beyond that, I know so little about what was going on with them, so it’s possible I’m maligning them.

MD: Well, you’re not passing judgement on the quality of what they achieved, are you? You’re simply acknowledging that the painting department wasn’t a movement in itself, which is what the sculpture department had become in the late 1960s.

AG: The person you should talk to in connection with the painting school is James Faure Walker. He moved from the sculpture department to the painting department in 1967. He was one of my first students, but I didn’t teach him anything (laughter).

By the time I fetched up at St Martins, there was a renegade, anti-Caro movement in the sculpture department; even among the people who were making Caro-esque constructed sculpture. Peter Hide, David Evison, John Hilliard, Gerard Hemsworth- they were all there in the year I started. The very first Forum I attended, they were on the panel, and they were all having a go at Caro, ribbing him; and of course, he loved that sort of thing.

Bruce McLean had already come and gone, and he’d rebelled, as had Barry Flanagan- he’d been involved in organising that notorious episode with John Latham, during which Greenberg’s ‘Art and Culture’ had been chewed up and spat out. Richard Long was by this point already doing his walks, and coming in with twigs from the Cotswolds and sticking them on the wall. Caro, Tim Scott, Phillip King and I were invited by Long up onto the roof at St Martins to view his latest work, and to critique it. We went up there, and there was a pile of sand- no, scratch that, not even a pile of sand, a puddle of sand- and we had to stand around and talk about it. Words were exchanged: to the effect that this was English romantic nostalgia-

MD: …for the sandpit?

AG: It wasn’t ridiculed; we tried to talk about it. But really, what is there to say?

MD: Was there an audience of students for this crit?

AG No, not on this particular occasion; but there often was. And the students were given free rein to say whatever they felt like saying, for or against, and we staff stood around in groups. Caro would typically come in on a Thursday, and say, let’s walk around, see what’s going on. It didn’t matter whether the student was Advanced or Diploma, if there was something to be seen, we would see it. We’d say to the students, we’ll have a look at yours, and yours, and yours- we’ll go grab a coffee and we’ll all meet at 11am. And then there’d be this open sort of argy-bargy…some people can function well under that sort of pressure; others are simply intimidated, obviously. But what you’d get after it was all over was members of staff who didn’t approve of this sort of thing coming round and saying to the stricken students, oh, don’t worry about it, they don’t know what they’re talking about. But I will say that, by and large, it was a public, open forum, and that’s how it worked, and that was what was great about it.

I’ve been in art schools where you go there in the morning, into a little cubicle, and the student has arrived late and has got virtually nothing to show you, and you have to look around until you find something, and you end up saying, oh, what’s this photograph about?

MD: So there was something essentially meritocratic about the St Martins method: you walked around and looked until you found something that stood out, regardless of who’d made it, and you talked about it.

AG: Yes. And it didn’t only happen when Caro was there; but it always did when he was, because he liked to do it.

Some of the people on the Advanced Course had pretty healthy egos in their own right, and were perfectly able to stand up for themselves, and to be confrontational, aggressive even, and say to us, I think you’re talking nonsense. Others would be more sheepish, or simply listen to what everybody had to say. It was only gradually, over a period of years, that it started to dawn on me that what Caro was doing was teaching from the perspective of his own particular way of working, and that anything he deemed to be lying outside of that would be roundly criticised. Typically he’d say: ‘Turn it upside down!’ The student would have been working all week on the thing, made out of wood and dowelling, and Caro would say, let’s have a look at it from underneath; and it would be turned upside down, and bits would fall off it, and Caro would pronounce ‘There! It looks better that way.’ This, I realised, was not the right way to go about things.

MD: His teaching had the outward appearance of a free exchange of ideas, but it was really a form of egotistical coercion?

AG: I wouldn’t put it that strongly, not quite. There were, for him, shall we say, certain ground rules for what sculpture could and couldn’t do: no closed boxes, for instance. Everything had to be open; and anything that was built in an architectural sense, again, no. This was how Caro’s own sculpture had evolved: it was a form of disguised engineering, if you like. Whatever engineering that was present in the thing was so dispersed that you couldn’t trace it; that was his style. But of course, there were other sculptors there, each with their own viewpoint; Phillip King, to name but one. Things came to a head, eventually, around 1977 or 1978; one particular advanced student had made a big sculpture in wood that was rather like one of David Smith’s Cubi. It rose off the floor, projecting this way and that, and it had some Brancusi-like wooden carving to it as well. It stood in gravity, it cantilevered, and so on. Tim Scott was there, and he gave a very logical, rational account of what the sculpture was doing, because it had certain resemblances to his sculpture also; all very convincing. And then Caro said, ‘Well, yes, but what you could also do is turn it upside down and put it in a niche in the wall.’ Which moved me to respond, you’ve just flatly contradicted everything that Tim Scott has said; and you can’t both be right.

MD: When you did actually get round to making your own sculpture, how much did you make?

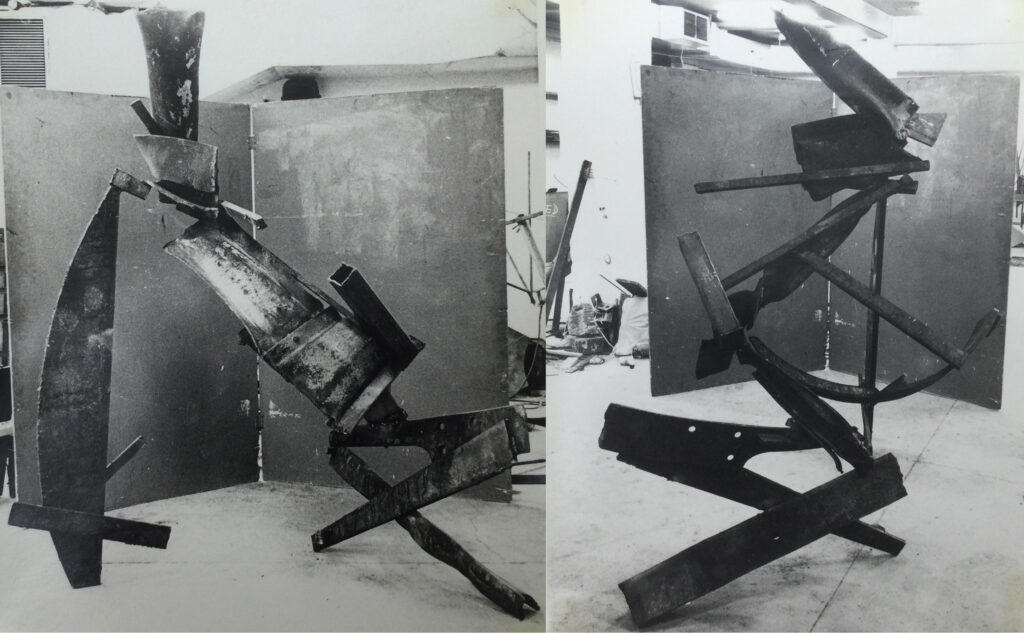

AG: Three or four, in the basement at St Martins. I was doing them after hours, after a day’s teaching, and it was physically exhausting.

MD: With technical support?

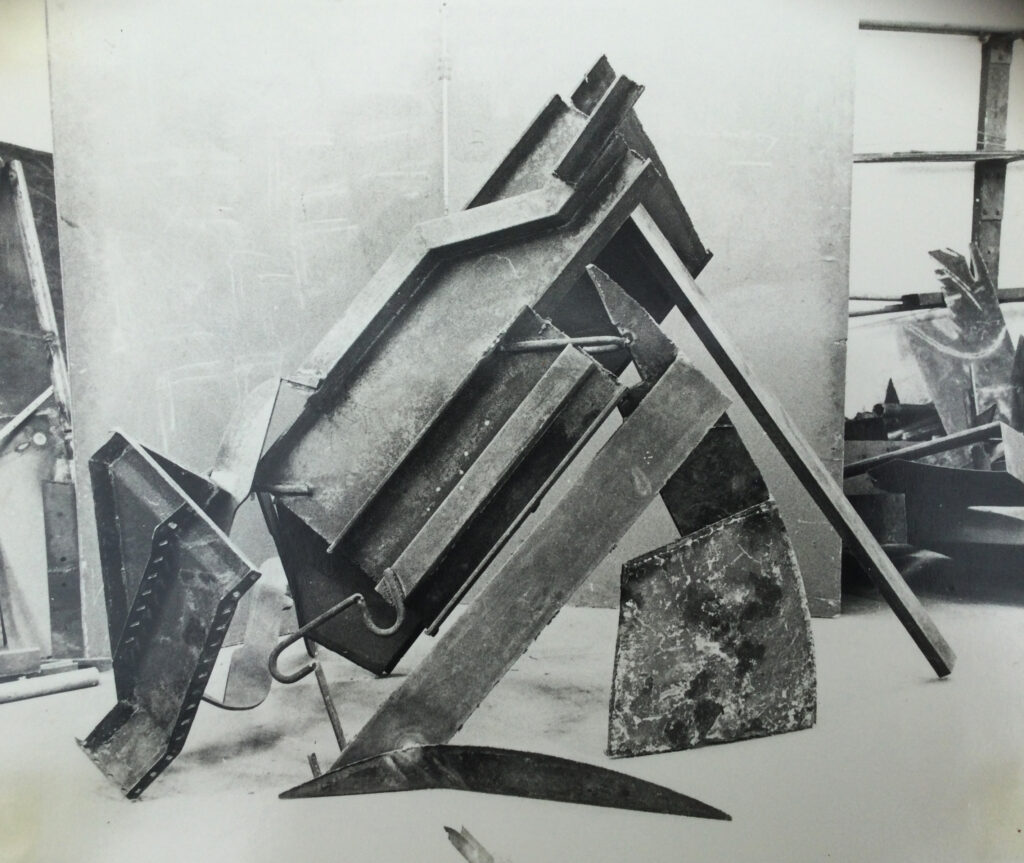

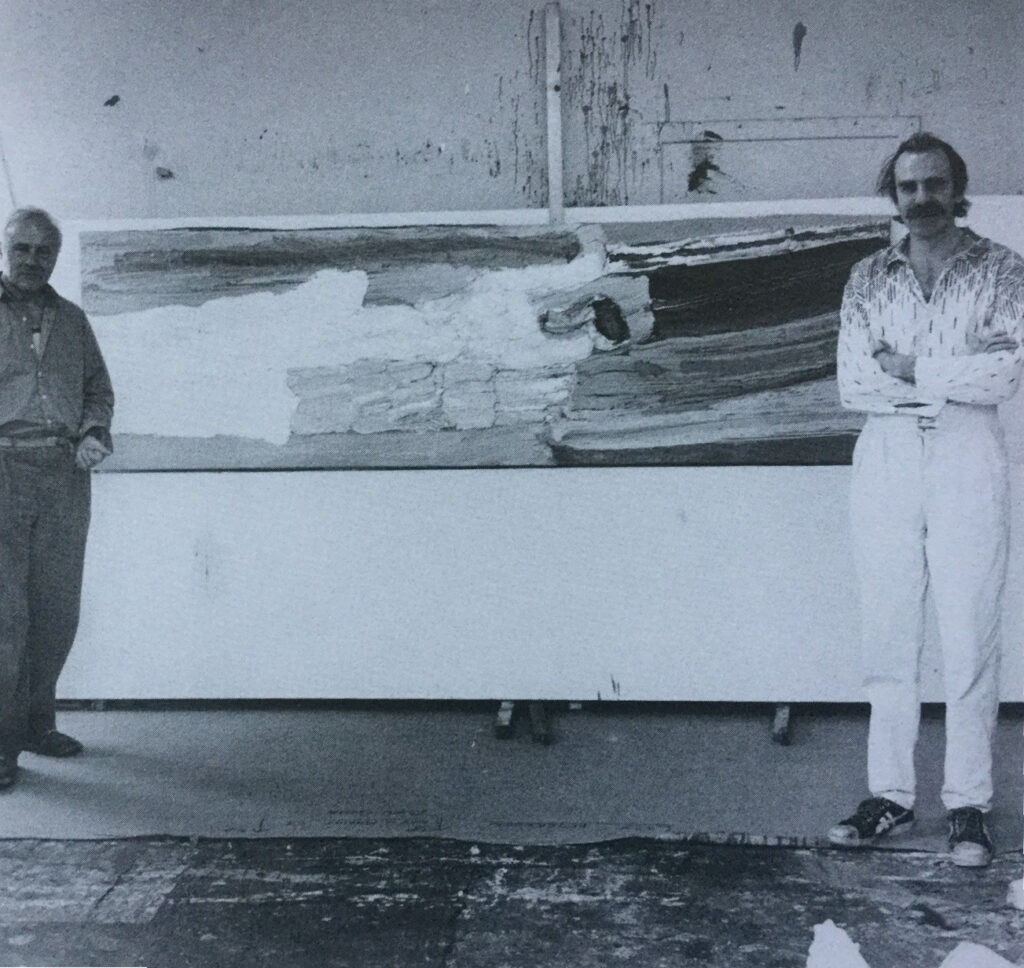

AG: Yes. Stan Brobyn taught me how to weld using the oxyacetylene. But that was so laborious, and used up so much gas, that I switched to arc welding. You’ve seen the photographs of my sculptures?

MD: I’ve seen a photograph, just one. What became of them? Are they still extant?

AG: Oh no no no. They just got broken down, and other people cannibalised the parts.

MD: Around this time, Noland and Frankenthaler made sculptures; did their work feature in your thinking, as a painter-turned-sculptor?

AG: No. It happened like this: I used to go off to the scrapyard in the van with the students to buy all sorts of scrap; and I saw this stuff, and I thought: I’ll have some of that. I retrieved some big, squashed steel pipes- they’d been through a guillotine and had their ends crushed-

MD: Pinched off, like sausages?

AG: Yes, or like ravioli (laughter). That was some of what I used. I was just learning as I went along…

MD: Do you view the works as a brief flare-up of a sculptural impulse that then subsided?

AG: No, I thought I might be able to carry on. In fact, I went as far as buying an arc welder, and hoping that I might get a studio space at Stockwell. But with ‘Untitled I’– the best one- Caro came in, and said, let’s have a crit of it, with Tim Scott…

MD: Yikes.

AG: I thought then, and still think now that it’s a good sculpture-

MD: I’m very fond of it. Although I believe it earned you a critical drubbing?

AG: It was described as a ‘Gonzalez Gouk’ (laughter) because it was sort of rustic as well, with all kinds of ironmongery. And here’s another one, ‘Untitled II’ which is sort of flatter, with this sort of bracketing, which was a found object. Of all of them, I think these two are the only ones that were any good…

MD: They’re putting me in mind of Caro’s ‘Flats’– was he busily noting what you were doing at this point?

AG: Oh no no no. Not in 1972, at any rate. It was the other way round: ‘Untitled II’ was derivative of Caro; but ‘Untitled I’ definitely wasn’t.

MD: I expect these were probably disliked on account of the anthropomorphic traces they carried?

AG: Oh, and because it was standing up…Caro’s sculptures were all laid out across the ground. And to top it all, ‘Untitled I’ had this kind of crown on it…

MD: Yep, you broke all the rules (laughter).

AG: And Caro waded in and said, you’re setting the students a bad example, doing this thing, it’s like a Julio Gonzalez-

MD: In other words, a backward step.

AG: Yes. But nevertheless, as I said, I happen to think ‘Untitled I’ a very good sculpture, actually.

MD: Have you got documentation of all the ones you made?

AG: There are two or three photos; but I’m really not trying to put myself forward as a sculptor. Anyway, being on the receiving end of a critique made me realise that something was amiss with the whole process. Caro kept asking, what’s your intent? What is it you want to do? And I had no fucking idea what I wanted to do (laughter). Most students don’t know what they want to do. To this day, if I’m starting a painting and someone were to ask me ‘What’s your intent?’ I’d say fuck off, I haven’t got an intent (laughter). I’m just exploring something, trying something on for size. To be able to articulate it in words before you’ve done it? No no no. But this was the way in which Caro would criticise students. And not just him: lots of tutors do this.

MD: But wouldn’t you agree that it’s a hell of a lot easier to work in a free, improvisatory manner in painting than it is in sculpture? If you’re gathering heavy, cumbersome pieces of scrap metal in order to make sculpture, aren’t you going to have to have the semblance of an idea of where you’ll be starting from, and where you’ll be heading, wouldn’t you say?

AG: Alright, granted, but the fact is, I really was just putting bits together to see what would happen. And when Caro asked me, what’s your intent here, in order to have something to say, off the top of my head I came up with this argument that since drawing had been pretty much banished from abstract painting, then perhaps sculpture was drawing’s true home? And I claimed I was drawing with the metal. And something in what I said must have struck a chord: because then Caro started doing just that.

MD: Caro’s ‘Table Sculptures’ are full of drawing, aren’t they?

AG: Yes, exactly. And it was around that time that he began making them.

MD: Your raising of this question of the role of drawing in sculpture prompts me to ask about John Panting. You rated him very highly, didn’t you? At least, you rated the sculptor he became; but the gist of what I’ve understood about your reading of his work is that you felt he started out by simply ‘drawing’ with lengths of steel, but then went on to shape space in a truly sculptural way?

AG: The gist of what was said at John Panting’s Forum session at St Martins, where he’d been invited to bring his work in- and whether I said it or someone else said it, it seemed to be the consensus view- was that he was using square-cut steel bar, the sort of material an architect would use for a staircase handrail, and that he was using it in an architectural way, without feeling it as a material; without sensing its weight, its pressure on the other elements within the sculpture, and so on. It was too design-y and too graphic.

There was a close link back then between what Panting was doing and what Bill Tucker was doing with his ‘Cat’s Cradle’ pieces, and his thin rod pieces which created trapezoid volumes in space; Tucker talked about the conflict between what you see and what you know: a rectangle doesn’t look like a rectangle when it’s rendered in three dimensions, and it’s receding away from you. He was very involved with the phenomenology of perception, and with gestalt theory. Panting too; and they influenced one another.

So, that was the critique of Panting’s work at that juncture. And what happened after that was that Panting underwent a huge explosion of creativity, and did some truly amazing stuff. I praise his late work in my second essay on steel sculpture.3Gouk, A., ‘Steel Sculpture Pt 2’, https://abstractcritical.com/article/steel-sculpture-part-ii-from-scott-tucker-and-panting-to-the-present/index.html

Most of my writing about painting has not been criticism, but simply responses to various exhibitions I have seen. I won’t really write at all unless I’ve been to an exhibition and been affected by it. For instance, there was a huge retrospective of Pissarro at the Hayward Gallery in the 1980s, and that prompted me to write; but I wouldn’t consider it so much criticism as an article about the artist and the work. My writing on Heron, again, is not so much criticism as an attempt to paint the big picture of the man and the work.

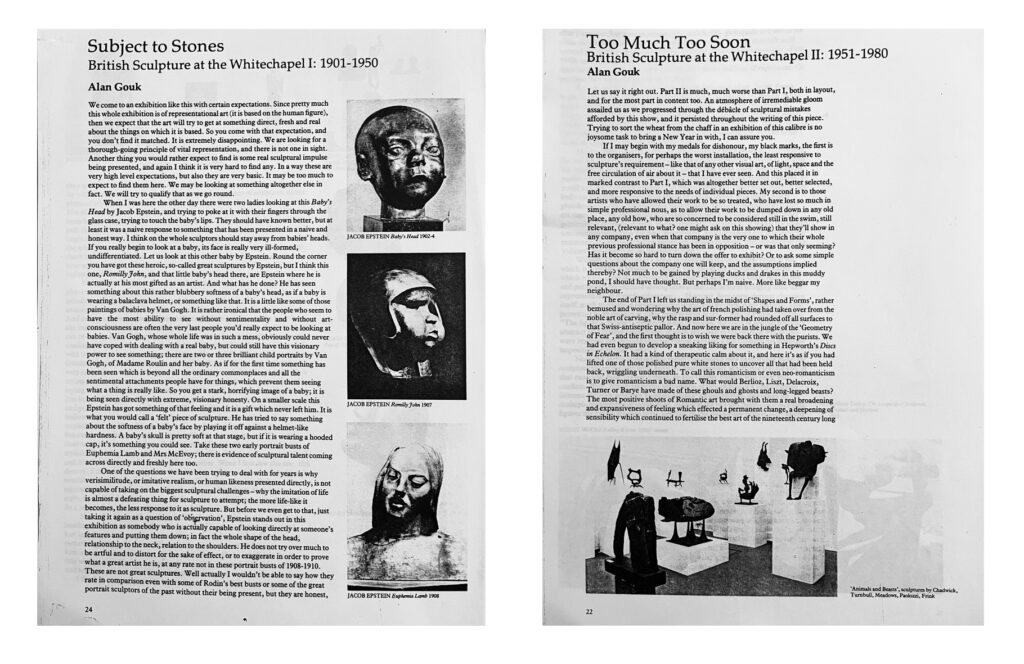

For me, the situation is completely different when it comes to writing about sculpture. The first major article I wrote about it was ‘Proper to Sculpture’, which was written in 1978 and 1979, and published in ‘Artscribe’ in 1980. At the end of 1976 I was recovering from a really bad bout of ‘flu that affected me for three months, and I hadn’t been able to do all that much apart from go to the library near where we were then living, in Stroud, and there I stumbled across a book called ‘The Sculpture of the World’ by Sheldon Cheney. There was very little text; it was a photographic exploration of world sculpture from the Venus of Willendorf, through Mayan and Cycladic, Japanese and Chinese sculpture, and so on…and looking through it all, I had a kind of revelation. Western European sculpture didn’t look all that good by comparison: its obsession with the nude body, expressed through the pictorial values of Bernini and Michelangelo, and in its twentieth-century manifestations, such as the work of Brancusi, its preoccupation with an African model of sculptural form that far outstrips it. Brancusi’s ‘Bird in Space’ looks like an over-refined piece of Art Deco next to the African works from which it supposedly derives. Henry Moore’s early stone carvings, good as they are, can’t hold their own next to the best of the Mayan carvings.

That’s where I started; and it developed into a critique of cubism, and of Greenberg’s view of modernist sculpture as having its roots in cubist collage. I was lucky enough to have the precedent of William Tucker’s book, ‘The Language of Sculpture’, which had been published a few years previously; it’s a forensic examination of all the pathways of twentieth-century sculpture that don’t depend on cubism. From there, the next thing to come my way was the big two-part survey of British sculpture at the Whitechapel, which began with Gaudier-Brzeska and Epstein, and on into the 1920s; and, not even realising that there was due to be a second part, I wrote a very severe critique of the first part. The second part kicked off with the ‘Geometry of Fear’ group- Lynn Chadwick, Reg Butler, Kenneth Armitage, Bernard Meadows, all the sculptors that Herbert Read promoted; then Caro’s early clay figures, and then Hubert Dalwood, Robert Clatworthy, and right up to Glynn Williams, who showed a carved stone ‘Mother and Child.’ (At Stockwell in 1979 he presented a huge wooden construction called ‘Rhino’, which I have no idea how to describe.)

Anyway, having applied my somewhat bitter and damning critique to the first part of the show, I could hardly pull back when it came to the second; so I was equally trenchant in my attack on it, and of course on the work by Caro included in it. And this was where my troubles with Caro really began in earnest; but I’m not going to go into all of that here.

Once my reviews of the two shows had been published, Glynn Williams piled in with ‘There sits our sulky, sullen Dame, nursing his wrath to keep it warm’– quoting Robbie Burns. So I wrote a reply which began ‘Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face, Great Chieftain o’ the Puddin-race!’ quoting Burns back at him; but they wouldn’t print it.

MD: Can’t imagine why not… (laughter).

AG: The point is, all my writing about sculpture is actual art criticism; I’m not a sculptor, so I applied a particular set of criteria based on my feelings about structure and form, and found in doing so that I had very little time for Tony Cragg’s plaster bottles laid out in rows, or for Richard Long’s work; I already knew, as I mentioned much earlier, what I felt about him from the time when he was a St Martins student.

So there’s a difference that needs to be understood. When I’m writing about painting, I’m writing as a painter, fully immersed in the practice of painting; but when it comes to sculpture, I’m writing with a set of ideas about what sculpture should be.

MD: When you’re writing about painting, it’s presumably with a greater sense of immediacy, because instinctually or otherwise, you’re measuring what you’re looking at and writing about against your own painterly practice…

AG: Exactly. Or against my own as-yet-unfulfilled wishes for my own practice.

MD: Also, it would be fair to assume that the painting you’re writing about occupies territory not too far distant from that occupied by your own work?

AG: Yes, absolutely, because I wouldn’t waste my time writing about something I didn’t like. I’ve only ever written about things that I’m- at least mostly- positive about.

MD: And because you’re not a sculptor, when writing about sculpture then all of it is in a sense fair game, because you’re equidistant from all of it, and feeling no bias? Although I should say again here that I rate the few forays you have made into sculpture very highly, and it’s a perverse quirk of your career that there aren’t fifty more of them, or a hundred more…

AG: No, no, none of these sculptors would ever consider me a sculptor. To be a sculptor you have to have done a great deal of work, not just two or three pieces like I have.

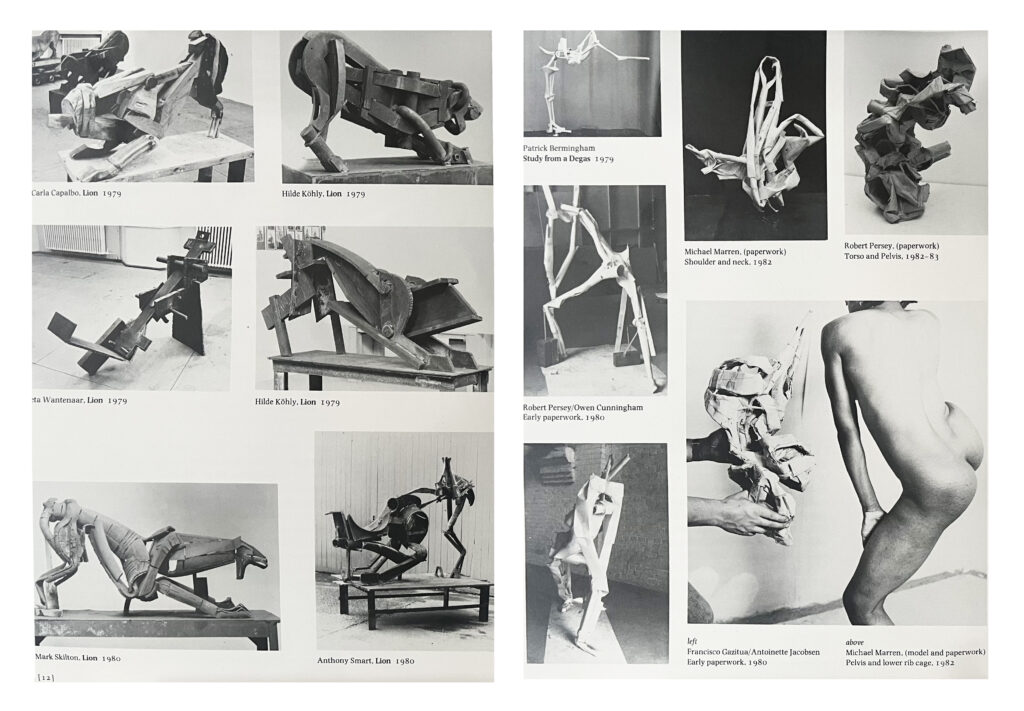

But anyway, the corollary to all that, or the sequel to it, is that the Stockwell sculptors, Tony Smart, Katherine Gili, Robin Greenwood, all picked up on these ideas I’d presented. My article, ‘Proper to Sculpture’, I first delivered as a talk, complete with slide show of comparisons between images of different works, at St Martins in 1979, and Peter Hide was in the audience. I was making direct comparisons; for instance, a New Hebridean sculpture against a Michelangelo…

MD Rather like André Malraux’s ‘Museum without Walls’?

AG: Exactly, exactly…although at that point I hadn’t read any Malraux. Well, Peter Hide piped up and said that I must have been reading Roger Fry’s last lectures, and I replied, no I haven’t; but I pretty soon did. I went out a bought a copy of Fry’s last lectures, and lo and behold, he had been doing a much better job back in the 1920s and ‘30s of saying the same kind of thing that I’d been saying; so I then began incorporating some of his ideas into the written version of ‘Proper to Sculpture’.

MD: And you feel that this critical position of yours vis-à-vis sculpture, that you’d arrived at by this point through all your reading and research, was something that Robin Greenwood et al came along and helped themselves to?

AG: Yes, they took up some of the thinking that was in ‘Proper to Sculpture’; but in the essay, I rule out the idea that you can take formal invention from figurative sculpture and transplant it into abstract sculpture, and they started doing more or less that. I then found myself in the position of defending the developments that Robin and his colleagues were making, even though I didn’t entirely go along with them; but they had been my students, and the fact is that they were doing very interesting things.

We had been finding that applicants for the Advanced Course were coming with slimmer and weaker portfolios, due to the practice of Foundation and Diploma Courses around the country of following the influence of fashionable tin heroes of the hour, with ‘Art Informel’ detritus, wire decked with feathers, ‘piss flowers’ and so on, with almost no sign that students had been encouraged to actually ‘make’ anything (in Tucker’s conception). So I decided to introduce the model’s body as a locus for understanding the physical reality of things in the world, in a way totally unlike the usual art school ‘life class’ conception. Simultaneously Tony Smart, who was teaching in the St. Martins Foundation Department, began a project working from an Ionian Lion in the British Museum, following a reading of Cheney’s survey. And when Tim Scott became Head of Sculpture in 1980, the first thing he did was to acquire a copy of the same Ionian Lion. It was intended simply as a student aid. But much to my surprise, some of the staff began to explore in the same way that the students had been doing. That’s how ‘Sculpture From the Body’ began.

You were asking me, what my criteria were when evaluating painting and sculpture. Well, when it comes to painting, I don’t have any criteria; you remember the articles I wrote for Instantloveland on Gauguin, Van Gogh and Matisse?4https://instantloveland.com/wp/2020/03/18/alan-gouk-gauguin-van-gogh-matisse-part-i-open-conflicts-hidden-affinities/; and https://instantloveland.com/wp/2020/05/12/alan-gouk-gauguin-van-gogh-matisse-part-ii-the-apotheosis-of-decoration/ I look and I compare and I make value judgements, based on what the paintings are showing me. When it comes to sculpture, the situation is different; I’m more detached, I’ve taken a position.

St Martins in Decline

AG: Do you really want me to go into the whole saga of the death of St Martins sculpture? because it’s horrendous…

MD: Yes and no. It’s useful up to a point, hearing all you’ve had to say about the sculpture school, as background and biography; but not if you feel it’s going to supplant consideration of the meaning of the work- both yours and others’…

AG: Well, where were you in 1983?

MD: I was a painting student at Middlesex Polytechnic, as it then was; the painting department was based in a converted factory space at Wood Green, just down the hill from Alexandra Palace.

AG: Your time there was precisely the time at which art schools started to come under this tremendous pressure from the CNAA5https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Council_for_National_Academic_Awardsto conform to their idea of what a Fine Art course should be. They had this philosophy- if that’s the right word- of imposing a modular credit system; they’d got away with doing it in the provinces, and now they were trying it in London, and the ILEA backed them. It’s a huge scandal, one that’s too big for me to go into here…

The rot had set in with the Coldstream Report,6from http://www.thejackdaw.co.uk/?p=1824: ‘It was inevitable that the Government would eventually have to get involved with art education. In 1959 William Coldstream, Euston Road School painter, principal of the Slade School since 1949 and, from 1958, Chairman of the National Advisory Council on Art Education, was asked by the Education Secretary to look into art schools, whose egregious anarchy was raising eyebrows in the papers. Part of the political objective in forming this committee was ultimately to make art education less expensive by, if possible, amalgamating institutions and departments, where this could be achieved, and by raising an agreed standard so that the eventual qualification became degree-equivalent – it would in fact take over a decade to integrate art schools indissolubly into the wider system of higher education. There was also a growing anti-élitist faction in government which believed that numbers in higher education needed to be dramatically increased to match levels of access to tertiary education witnessed abroad, where many times more young people were at universities. Coldstream was charged with making “recommendations dealing with the content and administration of courses for an award to take the place of the National Diploma in Design (NDD).”

The NDD had been created by the Ministry of Education in 1946. This Diploma was awarded as the culmination of four years of study, the first two of which qualified the candidate for a Certificate in Arts and Crafts. At the time of Coldstream’s appointment and his committee’s deliberations there were 106 art schools offering a two-year NDD producing around 1,700 students a year. The failure rate was just under a quarter, and the majority of those who passed who didn’t go into industry went on to teach at secondary level, where art was a subject taken far more seriously then than now.

The resulting Coldstream Report, a brief document of only twenty pages published in October 1960, and its fine-tuning supplementary addenda, called Summerson Reports, until the final Coldstream report in 1970, are frequently and flippantly claimed to have laid the groundwork for the destruction of art teaching. It has become customary to blame Coldstream and Summerson, both of them political and artistic conformists, for everything that has subsequently gone wrong. It is certainly true that the reports changed art’s organisation and certification, but in truth there is little in the wording of the main original report to suggest a path was being embarked upon leading to the state reached today where there are ‘right’ styles and ‘wrong’ styles, and where the learning of traditional skills has been all but eradicated. The Report encouraged liberalising tendencies and experiment, but always with the longstop of a necessary foundation of skill, an awareness of art history and a complementary general knowledge.’ which insisted that you had to have three ‘O’-levels and two ‘A’-levels before entering art education. There’s a famous episode, where Patrick Heron and Henry Moore went to see Margaret Thatcher when she was Minister of Education, and said to her, this is all wrong, the very people that you want to introduce into the art school system are the very people we would have kicked out. As Heron argued, the criteria for admission had previously been based on talent, on a portfolio of work; and so it was at St Martins right up until the point where I left, for the simple reason that the Advanced Course had no official recognition, and so it could do what it liked, and that was why it had become what it had become.

MD: This is what is so very hard to grasp now, that a course could pretty much magic itself out of thin air, and just run.

AG: But it did!

MD: David Evison explained this to me in my interview with him, and I was amazed. No accreditation, no external assessment of what the course was supposed to be about.

AG: No, there was none of that, and that was the beauty of it. People from all over the world were able to come, and the British Council backed it; their Foreign Government Scholarship Department would send people, and place them at St Martins, because it was a way of getting round all sorts of regulations. People came there on the basis of proven talent, as demonstrated by the things they’d made. And that’s the way it should still be, but isn’t.

The academic board at St Martins had affirmed, over and over again, that the Painting Department was a painting department, that the Sculpture Department was a sculpture department, and that they should be assessed on that basis. But the CNAA came in and said that the courses weren’t liberal enough, that there wasn’t a ‘fine art’ element; and by that they meant two days of printmaking, two days of photography, a little bit of sculpture on Wednesday, a little bit of painting on Friday afternoon. That was the kind of course they wanted, and that approach was geared towards building up the Film and Video departments, which soaked up an incommensurate amount of resources; and if there’s only a finite budget, then there’s less left over for anything else. At the time, those of us who spoke out were seen as conspiracy theorists, but this was exactly how it happened; and it happened the same way at Camberwell, they went through exactly the same trauma as we did.

MD: My own Foundation year at Central (when it was still Central, just before merging with St Martins) was, I believe, one of the last Foundation years anywhere in which one received an art education based around precepts concerning painting, sculpture and other media that had held sway since modernism first entered the arts. After my time, a philosophy of interdisciplinarianism very much influenced by conceptualism and postmodern theorising took hold, and all barriers between categories were systematically dismantled, for better or worse…

AG: Besides which, all the ‘old guard’ of painter-teachers was slowly squeezed out, and encouraged to give up. Patrick Heron wrote an article in the early 1970s, entitled ‘The Murder of the Art Schools’7Heron, P., ‘The Murder of the Art Schools’, The Guardian, Tuesday 12th October 1971: even then, the writing was already on the wall.

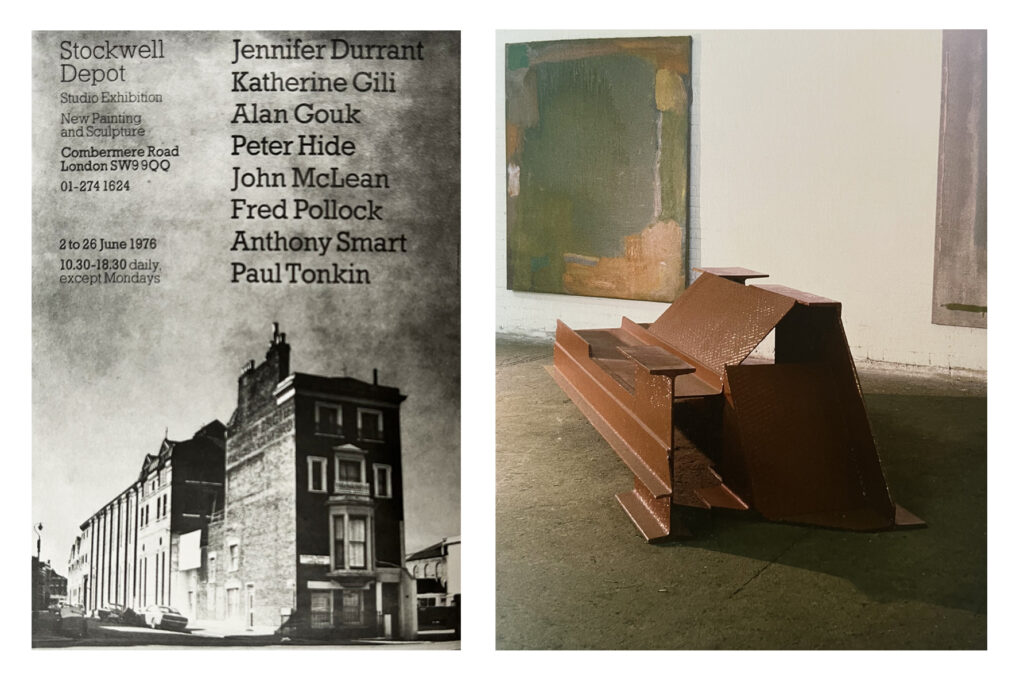

Stockwell and after

AG: I was disillusioned by the breakup of the Stockwell group8Alan Gouk writes: Stockwell depot was probably one of the first industrial/commercial sites to be repurposed and colonised by artists in the late 1960s, to be followed by St Catherine’s Dock, Wapping and others. Initially housing a group of ex-St Martins sculptors, once these first pioneers moved on it then became largely the domain of the sculptor Peter Hide, who occupied the largest area, and encouraged younger graduates to join him, both as assistants and as artists occupying their own spaces. As Sam Cornish puts it in his essay in the book ‘Stockwell Depot 1967-79’ (Published by Ridinghouse, 2015), Stockwell Depot has widely been understood as one of the key sites of sculptural production in Britain ‘between the New Generation and the end of modern sculpture.’

Painters joined with sculptors in occupying the working spaces: beside the main building was an annexe, which was shared by David Evison, John McLean, and John Golding. Above Hide’s studio, Jennifer Durrant had hers, and also on that upper level were Geoff Hollow and Kay Saunders.

In the summer of 1975, at the Spaniard’s Inn, Hampstead, after an opening at Kenwood House of Caro’s ‘Table Sculptures’, Peter Hide proposed to Geoff Rigden and myself that our group of painters should be included in the annual shows. We agreed, and set up a selection committee of Rigden, myself, Fred Pollock and Paul Tonkin. The first of these expanded shows was in the autumn of 1975.

The last Stockwell annual exhibition was held in September of 1979. The Depot continued to be used as artists’ spaces up until the early 1990s, but after the last of the occupants left, the structure fell into disrepair, eventually being demolished to make way for a block of flats.because I, more than anyone there, felt that it was a good thing to be doing, keeping a group like that together; but as soon as the first opportunities for individual success came along, it all disintegrated.

MD: Did you fight to keep it all going?

AG: Let me try to illustrate my answer with an anecdote. In 1979, Peter Hide and I realised that it was all falling apart- not on the sculpture side, the sculptors were all solid as a rock- but the painters were becoming more and more jealous and resentful of one another. Their bolshiness was being vented on one another; I can’t go into too much detail about it all, because it wouldn’t be fair to certain personalities. John McLean’s no longer with us, so there’s not a lot I want to say on that score, other than that we just didn’t get on, let’s put it that way. Anyway, Peter and I realised that it was all falling apart, so we put together a statement, a programme of commitment, if you like-

MD: A manifesto?

AG: Not so much a manifesto, more an agreement that stated that we were all working together, and so, if any one individual was approached by a gallery or a collector or a public body to buy a painting, then that artist would inform the other members of the group, and we would ask the potential buyer to look at everyone else’s work as well. We arranged a meeting at the Hole in the Wall, a pub in the arches at Waterloo, and prior to it, everyone had been posted a copy of the agreement for them to read and consider. Not all of the painters turned up to the meeting, but the ones that did- John McLean, Paul Tonkin, Geoff Rigden, all refused to sign. The sculptors all agreed; the painters all refused.

So, the 1979 Stockwell show was a group show of painters and sculptors, and for the first time we added outsiders in, who’d never shown with us before, including Mali Morris and Jeff Dellow amongst the painters, and Glynn Williams amongst the sculptors. Peter Hide asked a man called Peter Davies to write the catalogue introduction. I don’t know where Peter Hide had got him from, or where he came from, or why he thought it was a good idea to ask him in the first place; anyway, the essay Peter Davies supplied was a truly dreadful piece of writing, not just in stylistic terms, but also in terms of factual and typographic errors. I was furious.

A few months later, this same Peter Davies decided to curate a show in Poole, in Dorset, at a space called the Lemon Tree Gallery, or something like that; and he proceeded to do exactly what Peter Hide and myself had been fearful of, which was to invite some but not all of the Stockwell painters to exhibit. Of course, he didn’t ask me, because he’d heard that I’d been seething about his appalling writing…writing that continues to this day (laughter).

This was all confirmation of our worst fears: that some of the group were now going their own way. John McLean had always been bobbing along on the sidelines anyway, not really part of Stockwell, because his studio was separate from the rest, and because he and Peter Hide didn’t really get along; but now, everyone was pulling away and following their own course.

Well, I agree with what Patrick Jones has said: it’s a great shame that everything has broken apart. This is probably why Robin Greenwood’s whole project has taken off in the way it has, because there’s a need for that sort of thing; first his gallery, and then the Brancaster Chronicles, which, unfortunately, I’ve always said I didn’t want any part of, because I fundamentally disagree with privileging the internet over live exhibitions. I happen to think that one’s first view of a painting shouldn’t come via the web; one must go and see it in the flesh first. I also feel that the motives behind the Brancaster Chronicles were entirely promotional: they were all about getting a wider audience via the internet, which I feel is entirely wrong. I said I wanted nothing to do with it, and Tony Smart got very irate, because they wanted to video the whole process, and I argued that airing your dirty linen in public is not such a good idea. I think that it’s ended up with the videos being of greater importance than the shows; the publicity is all-important, the shows themselves are simply a ruse for getting the work onto the web. And the filming shifts the dynamic completely, from the timorous to the domineering. If the St. Martins forums had been video-ed, they would not have been the same. There would have been more grandstanding.

MD: My feeling about the Brancaster Chronicles– having participated in a few myself- is that they’ve got more in common with open studios than with exhibitions as such; and so I don’t personally find them problematic. If the videoing were to replace the live experience of the work- as you clearly feel it does- then no, it shouldn’t; but given how geographically spread out people are, and given how few opportunities there are to exhibit work-

AG: But most people just watch the video; they don’t go any further. For instance, there was the show put on in Greenwich a few years back9http://www.greenwichunigalleries.co.uk/brancaster-chronicles-in-greenwich 2017/: nobody went to it, it only existed for the night they were making the video of it. I went along a couple of days later, it was deserted, there was no-one there invigilating or greeting visitors. The few people I know of who went along later as well all said the same thing. It’s all a promotional exercise, and the work is secondary.

MD: I suppose I feel that we’ve all got to make our peace with digital reproduction in one way or another, because there’s no going backwards now, one is forced to have a social media presence, even if that’s merely the bare fact of owning a mobile phone. Once upon a time, I knew, and knew of, people who refused to own one. Who refuses now?

AG: I know. Pat, my wife, has put me up on Instagram, because everyone’s doing it, all of the time.

MD: I know, though, that it can’t continue the way it’s now going, because we’re approaching saturation point, and so I agree with you in that sense; but my own instinct as regards one’s work is that one has to get it out there, by fair means or foul.

AG: Of course. If you don’t exhibit, you don’t exist; but in my case, I really mean exhibit, as in have people come and stand in front of the physical work. A photograph, digital or otherwise, has never been and never will be a substitute. Photographs flatter to deceive: everything looks good on the internet.

MD: Anything backlit looks lovely, as a rule.

AG: I wish that there was a peer group for me to be a part of now. But all of it was torn apart by overweening personal ambition. Not that I’m putting us on the same level as the Abstract Expressionists…

MD Oh go on (laughter)…

AG: But the same thing happened to them. As soon as any of them started to get any kind of success, it was all daggers drawn: Clyfford Still claiming that he taught Rothko how to paint, Rothko claiming he taught Newman. I suppose in a way it’s all inevitable. I deeply, deeply regret the Stockwell split, and I fought hard against it; I dearly wished for us all to stay together.

MD: I sense from all that you’ve been saying that you do indeed harbour the strong instinct to move things along for everyone’s benefit, for the common good. To gather together and to promote and to help people..

AG: Patrick Heron did exactly the same thing. He lobbied on behalf of his painter friends; for all the thanks he got for it.

MD Let’s talk about the post-Stockwell years…

AG I see the Stockwell years as wilderness years, because I was trying to get out from under the influence of the paintings and painters I’d encountered when I’d been in New York, and subsequent to that. I’d gone for the messier side of Larry Poons’ work, and rejected post-painterly abstraction; I was trying to paint ‘brushily’, touching the whole canvas surface. If you take Morris Louis’ ‘Veils’, for instance, they come about via a process, and there’s no sense of the canvas being touched or brushed; the paint is a sort of phenomenon that simply happens. I was trying to get away from all of that, but not all of the others were- the Stockwell painters were far from being a unified group in terms of their attitudes. John McLean, for instance, was very strongly influenced by Ken Noland and by Jack Bush, all the way through the 1970s and into the 1980s.

I realised, after the Hayward, that I couldn’t go on doing the sort of paintings I was doing, which were kind of heaving, using things to squeegee the paint and scrape it around, edge to edge. I think they’re good paintings, but they lacked just exactly those qualities that I’d seen in Heron, the specificity of scale, the directness of colour; I felt I had to make a big change, and I started working on a smaller scale, in oils. At this time my studio was in Chiswick, in a narrow passageway that takes you down towards Island Records. it wasn’t much bigger than the room we’re in now, and the paintings each took up the entire wall, once they grew big again. But in 1981, 1982, 1983, I worked on a relatively small scale; I wanted to paint a more painterly sort of painting, but one that was tangible and specific. I started using broad wedge shapes, horizontal, overlapping. I had a joint show with Geoff Rigden, and although hardly anyone’s ever written about me, the best criticism came after that show, when a guy called Michael Billam described the paintings like this: ‘Alan Gouk’s paintings certainly don’t ingratiate themselves at first sight of their thickly applied paint surfaces, where the edges of marks rear up in spiky ragged ends, like waves rebounding from a harbour wall. I would guess that this quality is adventitious but stems from a strategy which allows Gouk to make decisive adjustments to the work in progress by knifing or scraping in solid swathes of colour of a predominantly horizontal or vertical orientation, as if Cezanne’s late deliberate brushstrokes were re-writ large, fat and juicy […] Gouk is ploughing an individual furrow.’10Billam, M., Artscribe no.39, 1982

And I thought, good God, is that what I’m doing? It’s a great description: it captures exactly the feeling the paintings have, of something that hits and spreads. But it should be noted: the ‘large, fat and juicy’ brushstrokes weren’t single strokes- they were multiple strokes that formed into a wedge.

MD: The first time I ever saw your work in the flesh was at the Riverside Studios in Hammersmith in 1987. I’d read about the show in ‘Time Out’, and I recognised your name from the Heron Barbican catalogue essay, but I had no clue at all about what sort of painting you made. So I went along, and I was very impressed; I’d not encountered painting like yours before, and the sheer horizontal extension of the canvasses was something new to me.

AG: By then, by the time of that show you’re talking about, I’d stopped using acrylics and switched to oils; I’d wanted to get away from the very clogged impasto I was getting with acrylic paints, but at the same time I wanted a firm surface. The solution, I felt, was to go for the sort of horizontal spread that you’re describing, so as to get away from the sort of thing I didn’t want; specifically, I wanted to avoid blocks, in the sorts of ways that Hoyland had been using them. I, like Hoyland, was working out of Hofmann, if you like; but in my case, out of Hofmann’s painterly side.

MD: What I liked about the work on show at the Riverside- apart from the colour, and the materiality of the paint- was something that I now understand Michael Billam picked up on as well, in the quote you’ve shared with me, to do with the harbour wall and the wave hitting it: there was a pitch and a roll to all of them, and a, what do you call it? a yaw in their rhythm, a feeling of twisting and pivoting around a vertical axis…

AG: Well, that’s how I got out of the Stockwell era, and into what followed it; and I would say that with those paintings and others from around the same time, I found my mature style. My work has been a kind of theme-and-variations around this ever since. I did find myself so strongly influenced by the Matisse/Picasso show at the Tate in 2002 that I adopted an approach based around use of thinner paint; but I’ve since returned to the concerns that we’ve just described. Let’s just say: if I hadn’t been painting like waves hitting a harbour wall before Michael Billam made the observation, I certainly was afterwards. It was a quite brilliant insight on his part.

MD: I’d like us to talk now about the work that you made as you moved beyond Stockwell; from being part of a collective that had any sort of traction within the culture-

AG: Even though that collective, and what it stood for, was heavily criticised?

MD: Yes, but even so, it was being talked about, and noticed; it hadn’t at that point become marginalised.

AG: I would argue it was very much marginalised from its inception; we were outsiders all right, and nobody was interested, unlike how it went from the very beginning for Damian Hirst and his Goldsmiths cohort. The difference being, of course, that theirs was a very different kind of art, which swiftly became flavour-of-the-month with very little difficulty; that, and the fact that they knew how to promote and to strategise and to benefit from it.

MD: Well, it was post-Warhol art, wasn’t it? Made with a careful eye on marketing, and on what reproduces easily, and had an easily-apprehendable message, and carried a hefty dose of sensationalism; as the title of the YBA’s RA show, ‘Sensation’, came clean about…

Anyway, the book, ‘Principle, Appearance, Style’ came out in 2008, correct? I feel like I have some grasp of the work you’ve been making since that milestone, but it hasn’t all been rounded up in published form…

AG: Funnily enough, there’s as much work been made since that book as there was gathered and reproduced in it; I’ve done an awful lot of work since then.

MD: Am I right in thinking that you’ve been deploying plasterer’s tools, or something similar, to apply the paint to the recent big paintings? To produce those thick wodges and wedges of pigment?

AG: No; all these recent big paintings you’ve seen, they’re all done purely with the brush…

MD: Big old brushes, then…

AG : Well, they all employ multiple techniques, multiple ways of putting the paint on; and what I often do is squeeze the paint onto a surface like that [holds up large hardbacked book] and apply it to the canvas. And I’m not the first painter to paint in this way.

MD: Of course you’re not. Your nemesis, Gerhard Richter, to name but one, has been squeegeeing paint on for decades now…

AG: Yes, and this way of painting, that he’s made a name for himself doing, what he’s doing is repeating a format that was all the rage in the late 1970s: trowelling the paint on. And if you look here and here in ‘Principle, Appearance, Style’ [opens copy of book] at ‘Wild Orchid’ of 1978, and ‘In the Wake of the Plough’ of 1979, there I am, doing it…

MD: And what implement were you using at the time, to get that much pigment on, and so thick?

AG: A coal shovel (laughter). And here I am, doing it in 1978. Richter started squeegeeing about fifteen years later…

The reason I made those two paintings, and others like them, was that I had been influenced by both Poons and Olitski. Greenberg had said something to me about going right to the edge, rather than the painting containing something, as it were; exactly the opposite advice to what he’d given Patrick Heron, twenty years previously. This is what I mean when I refer to that Stockwell period as the wilderness years: every time Greenberg came over to the UK, Tony Caro would bring him round to the Stockwell Depot and get him to crit our painting; but he only ever said a few words-

MD: How many visits did he make?

AG: I’m not sure; there were two or three visits that I was aware of; no, more, actually, because he came several times solely to view sculpture, and he only came to view paintings twice, in and around the times when the annual Stockwell shows were on…Anyway, my point is, these are wilderness years for me, because I kept trying to get away from all this influence he was bringing to bear, and it kept coming back at me. So in one sense, I was very fortunate not to be chosen for the Hayward Annual in 1980, which Hoyland curated- an episode I’ll elaborate on- because it meant I had a kind of clean break, and I was able to change course.

MD: Do you think that if you’ve stayed within that Stockwell circle of influence, you’d have kept with the ‘house style’?

AG: Well, no, all I can say with certainty is in a sense a negative, that I wouldn’t have developed in the way I subsequently did. I don’t see there as having been a ‘house style’. What characterised my paintings was a desire to bury post-painterly abstraction, which can’t be said of John McLean, or of Fred Pollock, for that matter.

MD: I’ve been looking at these various catalogues of your work from the last decade or more- such as the catalogue for the group show that Robin Greenwood brought together under the banner ‘High-abstract’11‘High-abstract’, Poussin Gallery exhibition catalogue, London 2011 …and what strikes me about a great deal of the work made by you in these catalogues is that it feels almost tailor-made to fit a definition I found in Hans Hofmann’s writings, where he says

‘Out of a feeling of depth, a sense of movement develops itself. There are movements that swing into the depth of space, and there are movements which swing out of the depths of space. Every movement in space releases a counter-movement in space. Movement and counter-movement produce tension, and tension produces rhythm.’

I feel that is very apt, especially in relation to your last show at the Hampstead School of Art, where you seemed to have arrived at a combination of what in one way has to be seen as a kind of stark simplicity, together with this extreme richness of the colour, and extreme physicality of the material; and looking at the paintings, I had a strong sense of your working on them, establishing these swinging, almost metronomic movements, which seems to me to be the principal way in which you take possession of the long horizontal. Do you recognise this sort of description?

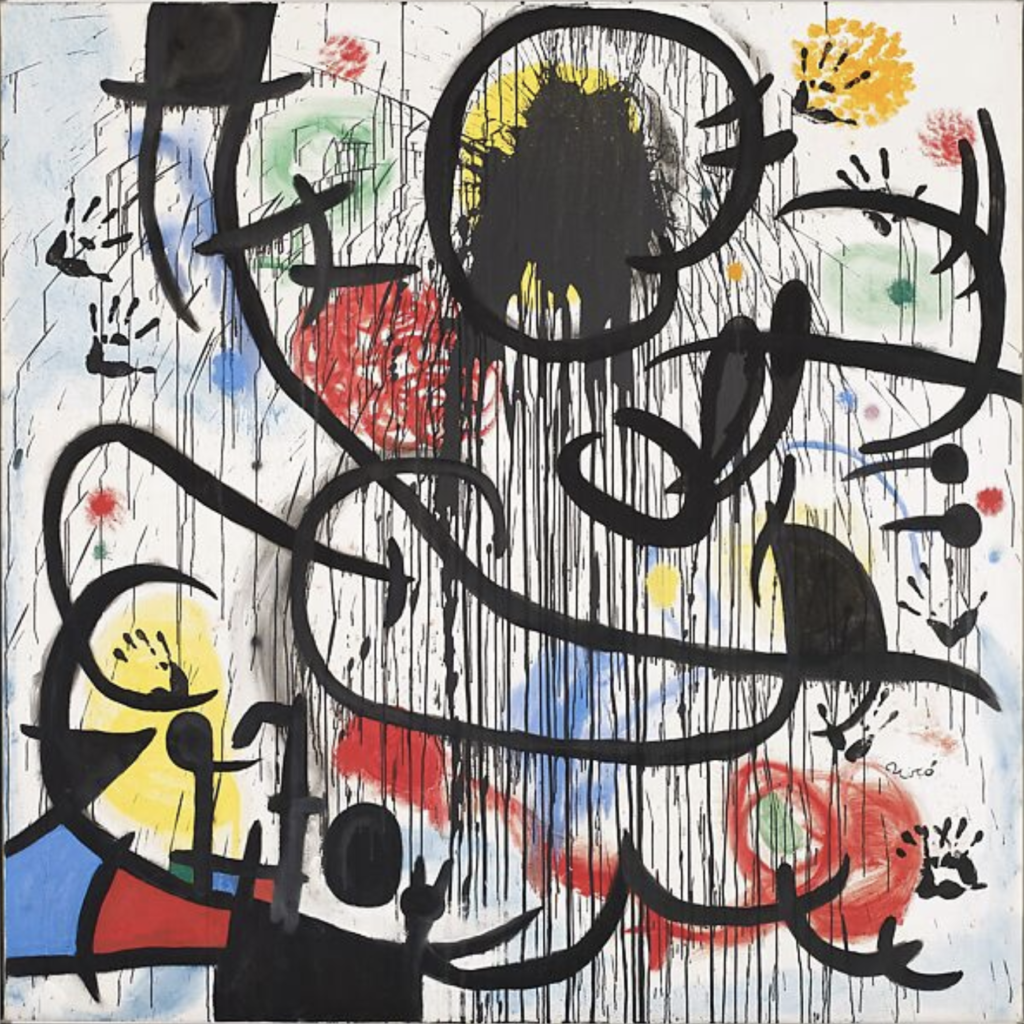

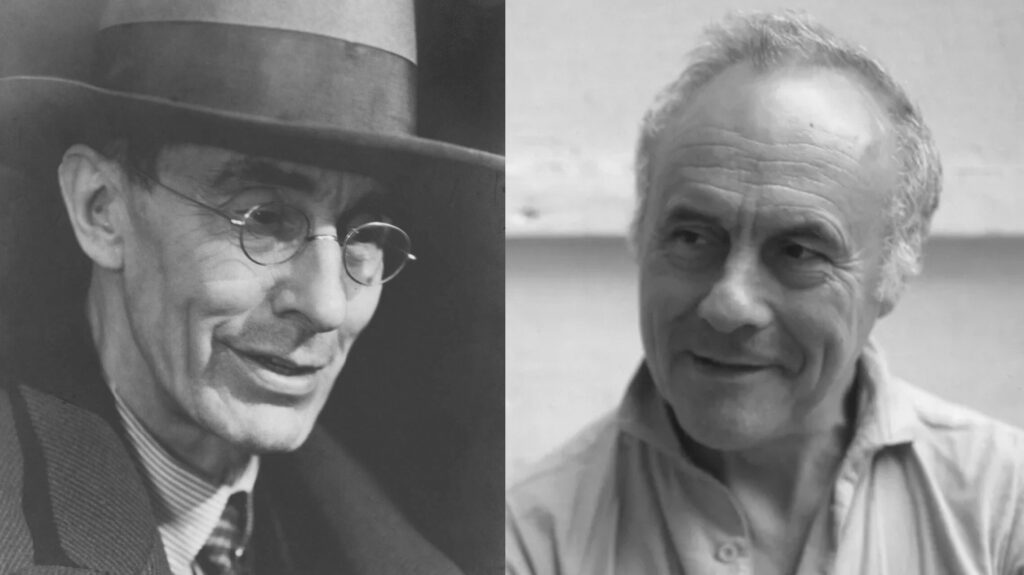

AG: Well, there are so many things in painting that one can’t do, because people such as Hans Hofmann have already done them, they’ve been there before, and beyond them, people such as Hoyland have developed the things they’ve done in particular ways; and with Hoyland, once he’d seen the opportunities in Miro, began to use drawing and shapes in ways he hadn’t done before. I have said elsewhere that he didn’t so much assimilate Miro as assault him, because you can’t assimilate everything about a painter, that simply leads to imitation. Because of the past precedent of another painter, and because of the anxiety of influence, there are certain things one just can’t do; and one of the things I can’t do is figure/ground, where you have an open, transparent space in which shapes and colours are floating or deposited. It’s too Hofmannesque, if you like.

MD: I remember coming across an essay on Hoyland written by Bryan Robertson in an old edition of Studio International from the late 1960s, in which he says that a danger Hoyland was working hard to avoid was just that trap of figure/ground, of placing a form in the painting that read too much like a thing in a place, like a sort of abstract ‘cow’ grazing in a colour ‘field’, or words to that effect…I can see this sort of aversion at work in the paintings you’re making now, you’re taking enormous pains not to let anything ‘drop back’ into fictive depth.

AG: Yes, that’s how it’s been for me for a long time now.

Clement Greenberg wrote a very good book on Miro: in it, he says that Miro’s art is inimitable because it’s so synthetic, because he’s absorbed the influence of so many artists, particularly Klee, but also Kandinsky, the cubists, and the surrealists. But the essential thing that has to be understood about Miro is that he energises the ground of the painting; he almost renders it as a magnetic field. It’s not a passive container. And this was the thing that Heron, too, so abhorred: the passive, lifeless ground.

Hoyland saw this in Miro: that the grounds of the paintings were electric, pulsing with life, alive with possibilities, and the best of Hoyland’s paintings were the big squarish ones where the entire surface was spattered, almost like the sky at night, in which he was rendering the whole painting active before beginning to draw his big shapes and whorls into it. This side of Hoyland comes from Miro, but is a development of it. And of course, Miro himself in his later years was responding to what the Abstract Expressionists, especially Gottlieb, had made of his earlier ‘magical fields’. And so it goes around.

So, where am I? I can’t do Hofmann’s transparent fields and I can’t do Hoyland’s spattered ones. If I did, it would be obviously derivative. My painting has made its way to a more robust, physically touched surface; but this isn’t a recent development, it’s been going on for a long while in various forms.

MD: It’s now- what?- thirty-five years since the show at the Riverside Studios where I first encountered you work; and this robustness you talk about was very much evident to me then, was in fact the most striking thing about the work for me.

It interests me greatly, you talking about what you can’t do, and citing the artists that have done it. In a way, you’re offering the same argument, in explaining why there are things you can’t do, that so many people offer now for not being able to do anything; for not being able to formulate any kind of fresh statement at all in paint.

AG: Well, there’s something marvellous that Greenberg said: that the painter’s world is one of ‘confined surprise’. Meaning, it’s not surprise in the sense of an elephant’s trunk suddenly emerging out of the canvas, or anything like that; but that, within certain formal and stylistic limits, there’s an element of surprise. It’s to do with somehow keeping the painterly qualities of good painting going.

It doesn’t matter that there are people that see the entirety of painting as dead; it’s not. As long as people come into a gallery, see a painting, and wish to emulate its level of achievement, it’s going to remain alive; and my art is consolidatory, in that sense, it tries to keep the succulent life of painting going.

MD: There’s the notion- I have it in my head that it was first put forward by WH Auden, but I couldn’t swear to it- that in the history of any art form there are the explorers, and then the colonizers; and perhaps we can see visual art now in those terms, that there is nothing more for the explorers to do?

AG Well, yes, at the moment I think that is true, because there have been so many explorations in so many different directions, and most of them have led to a dissipation of painting’s potential. To my mind, now is a time for consolidation of those best virtues that painting has: and that’s what I’m about. Whether or not people now think painting is dead means absolutely nothing to me; it doesn’t bother me in the slightest. And that’s why I can’t really understand what the fuss of the last thirty or forty years has been about: commentators like Waldemar Januszczak declaiming on the death of painting on BBC2’s ‘Late Show’ whilst making a tidy living talking endlessly about the very thing he’s given up on as dead…he can say whatever he likes, it has absolutely no effect on me.

Hoyland, Heron, and the Hayward

AG: I think it’s worth my talking about John Hoyland and the 1980 Hayward Annual, and the events that led up to that whole episode.

I’d been friendly with John Hoyland when I’d been at the British Council, and afterwards; and he’d been interested in the whole shaped canvas thing, and he used to come and see me when I was making them. The British Council selected Hoyland to show at the Sao Paolo Biennale in 1969.