John Bunker on Frank Bowling: ‘Beauty Doesn’t Stop Still’

The premise of the exhibition ‘Inventing Abstraction 1910 to 1925’, that ran at MoMA New York in 2013, was that abstraction was not a single, monolithic movement, but a complex network made up of individuals connecting with one another, talking, writing, travelling, organising exhibitions- big and small -across the world. A hundred years on from these events, Frank Bowling’s art and life continue to embody and renew these free-wheeling values of restless travel and responsiveness to people, ideas and places.

Bowling’s is a generous, open, yet protean and restless art, that could never be bound by art-doctrine or defined by borders, whether geographic or intellectual. His career took off amidst the optimism of the post-war period, the infectious dynamism of the civil rights movements, and the hopes for a post-colonial world; and he forged an original, prismatic understanding of the potential of painting within Modernism and abstraction that has sustained his practice till the present day. While fashion and zeitgeist have turned against such approaches to favour either polemical figuration, institutional critique or conceptual concerns, Bowling remains committed to the pursuit of a personal kind of lyrical abstraction that draws sustenance from a deep engagement with the history of painting, and with British painting in particular. Bowling is way ahead of us: only now are we learning about the dynamic histories of the ‘Black abstraction’1https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/changing-complex-profile-of-black-abstract-painters-2452/ of which Bowling has been and has remained a major transatlantic innovator.

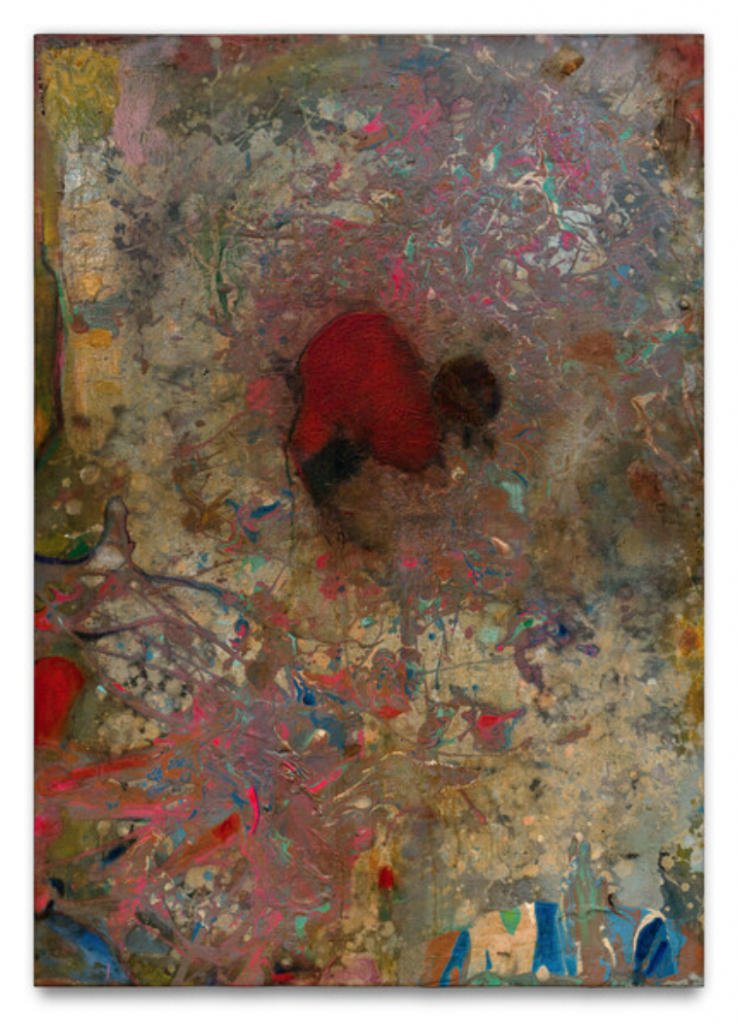

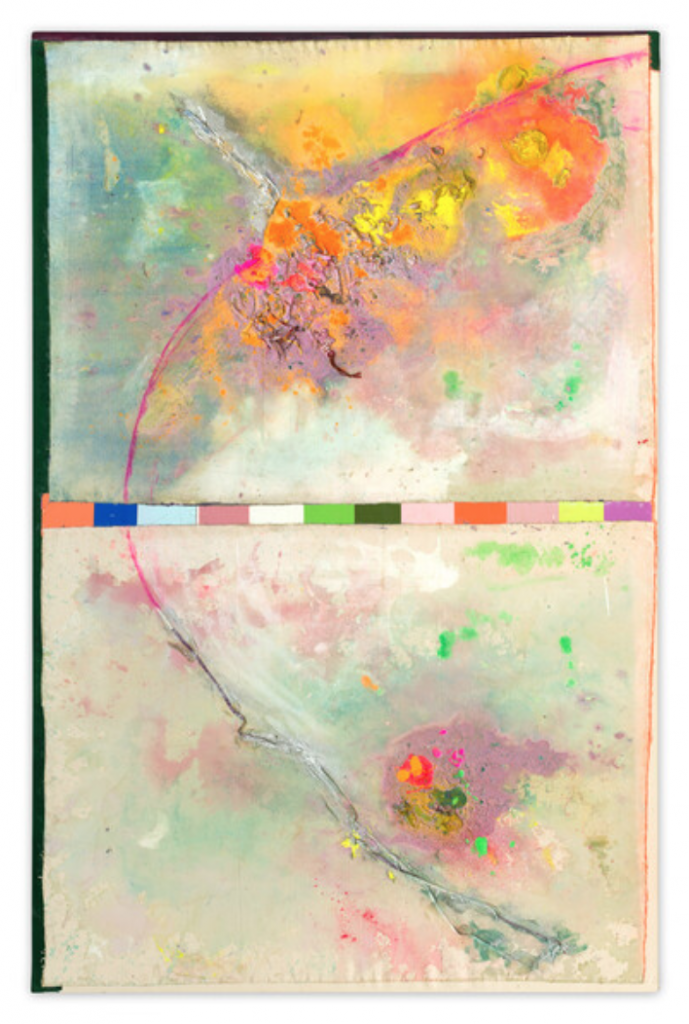

Although abstract and process-driven, Bowling’s art communicates something peculiar to human perception that one can immediately respond to and empathise with: for me, it bodies forth a particular kind of abstract beauty, born of a colossal reach of imagination, painterly intelligence and historical understanding. But there are problems with this word ‘beauty’: it has become either freighted with too many ideological connotations; or reduced to an empty signifier. Bowling acknowledges the concept’s inherent instability: he has said that he ‘is on the side of beauty, and beauty doesn’t stop still.’ Our perceptions of, and responses to, the idea of beauty are mitigated by a complex set of sociological and political factors. It would be easy to romanticise artworks as sacred symbols, lodestars of an uncomplicated and direct communion between a human being and nature. But this would fail to do them justice: they are embedded in a complex, constantly-evolving cultural and societal structure; they never ‘stay still’. Bowling is deeply aware of painting’s complex ties to history, a history characterised by periods of deep conservatism, but also by moments of great change, such as the convulsive transformations that painting underwent at the beginning of the 20th century. Rather than making it do his bidding by representing aspects of the real world, or enacting some conceptual conceit, Bowling insists that the paint leads the way. In this he is uncompromising; for him, painting’s subject matter is the paint itself. This, however, is only the beginning of the journey: he is always pushing the possibilities of paint past their limits, into that space of experimentation, that liminal realm between tradition and its undoing, where contemplation yields to action like the perfect silence before a summer storm.

It is the countless colours of the human temperament, and how that temperament is shaped by its environment, that the art of painting, over thousands of years, has been peculiarly able to express. Frank Bowling, over a sixty-year career, has continued to push that project forward, and has, in the process, marked out new pathways for abstract painting. He forges ahead, making ambitious, visceral and, yes, beautiful paintings.

4 thoughts on “John Bunker on Frank Bowling: ‘Beauty Doesn’t Stop Still’”

Comments are closed.

John, I would be very curious to hear Frank’s view of ‘Black Abstraction’, and whether this art world category has meaning for him. John Yau consistently brings up race and heritage on the site, hyperallergic.com. My own background is working-class Welsh mongrel and not at all groovy, despite great friendship with Caro, Hoyland and Frankenthaler. Who are Frank’s comrades in arms?

In 1969 Frank Bowling organised ‘5+1′, an exhibition in New York that showcased black artists exploring abstraction. It included Melvin Edwards, Daniel LaRue Johnson, Al Loving, Jack Whitten, William T. Williams. Bowling took part in the early debates around ideas of what it might mean to be a black artist, and whether such terms were useful or desirable. He wrote extensively on the subject in ‘Art News’ in the late 60s and early 70s. Bowling took strength from spending time with other black abstractionists during the 60s while acclimatising to New York life- but friendships were made across the art world and across racial divides, with the likes of Larry Rivers being great supporters when Bowling first moved there. His identity as a British artist, Guyanese by birth, meant his perspective was always slightly different from his African-American colleagues (he was the ‘+1’ of ‘5+1’.) It’s important to remember that Bowling found his love for painting in the UK: he was taught painting at the RCA. He did not arrive in the UK as a fully formed artist, like fellow Guyanese painter Aubrey Williams did. Although many have talked of Caribbean or tropical colour in Frank’s work, I would argue there are great paintings of his that use colour characteristic in feeling of the northern hemisphere, and which nod to the likes of Turner, Constable and Gainsborough. Yes, he became close to Greenberg and stayed close for a long time; but Frank made friends and important contacts that were refreshingly diverse, such as the world renowned novelist and poet Toni Morrison, the poet Frank O’Hara and curator Okwui Enwezor. Restless intelligence, curiosity and courage meant he was never in anyone’s pocket. This independent spirit can, of course, work for or against one, depending on time and circumstance…right now it is working for him, and for all the right reasons…

Thank you John, I would certainly agree about the quality of Frank’s painting. The art world can be an arbitrary and fashion-fuelled place, New York in particular. Living on two continents presents practical, less glamorous problems, such as having a bed for the night in both. Cheap hotels (called ‘Flop Houses’) were unsafe and unpleasant, and I remember sleeping in a rolled-up carpet in a church after a visit to the ‘5 Spot’ to see Thelonius Monk play. My point is that Sir Frank was straddling very different worlds, which takes people skills, as well as talent, which in his case was obviously available. With so many huge galleries such as Knoedler and Sotheby’s being caught up in fraud on a mammoth scale, the aspiring young artist might find not only difficulty accessing marketing, but the whole thing ethically unattractive. John Yau has mentioned he gave up writing for ‘Art Forum’ et al as they only wanted to talk about successful artists. I actually wonder if the system, like capitalism, and the internet, as a result of social media, is on the verge of collapse. This may not be a bad thing for young, aspiring painters, but it will take a great deal of organisation to replace the bankruptcy of corporate ethics. It is great to see Sir Frank’s success, and I wish him well.

Try this- https://www.nytimes.com2021/04/30/design/frank-bowling.html?referring Source=articleShare Wonderfull pictures of him at work with his family