Matthew Maxwell: The Five Rules of Rhythm: ‘Electronica from Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers’ at the Design Museum

It’s been said that there are no new ideas in art. You just have to keep repeating them because nobody ever listens.

That there is a relationship between the visual arts and music isn’t a new idea, but in The Year of Covid, an exhibition celebrating a musical form best experienced in a sweaty miasma of shared exhalation seems like a bizarre anthropological aberration from a very, very distant time. It’s a dislocation that lends a special kind of poignancy to the Design Museum’s ‘Electronica: From Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers’. Masked up, socially distanced, entry tightly scheduled and policed, the experience feels like the absolute antithesis of rave culture, which was characterised by its embrace of chaos and a gleeful swerving anything resembling risk assessment. But even if the whole acid house scene was never your thing, this exhibition does a good job opening a steamed-up window onto a musical and cultural movement that not only did what all good Pop should- confuse and annoy, while subverting the assumptions of quality and format that preceded it- but also works very hard to illuminate why creators like the Chemical Brothers were so influential. Not only in music, but in the visual languages that developed as corollaries to the celebration of Modernity that synthesised sounds came to represent.

At the heart of it all, of course, is rhythm. Faced with the commercial necessity of featuring electronic music on Top of the Pops, the show’s producers were stymied by how to feature musicians who didn’t actually play any instruments. Sometimes they didn’t even sing! Electronic music provided no performative spectacle, because the audience were the performers. Removing the necessity for instrumental virtuosity pushed the ownership of the experience back to the listener. Similar to Punk, ten years or so earlier, electronic music was something anybody could make in their bedroom with just a few basic tools and a minimal formal knowledge of music. Its power was the iconoclasm it proposed. ‘Let’s put the show on right here in the barn!’

But the power of rhythm goes back way beyond and long before the invention of the Roland TR-808 drum machine. We humans are drum machines. Rhythm is how we make sense of time on a human scale. Time is subjective. An hour occupied feels like a minute bored. And the timeframes of life vary enormously: our breath, heartbeat, fertility, REM sleep, even the subtle pulses of neurological activity – even thinking – all deliver a drumbeat that accompanies us from conception to death. And where there is no rhythm there is no life. In art, and especially in abstraction, the Formal Elements, line, texture, form, etc. are fugitive – close your eyes and colour disappears. Without touch, texture is meaningless. The one constant formal property we can never escape is rhythm.

It’s not surprising, therefore, to see how ubiquitous rhythm is in all art forms, not just dance music. The centrality of rhythm in our physical nature means we respond to its beat on an emotional level that is profound in the truest sense of the world. The neurological effects of repeating patterns, whether they be sonic or visual are well documented as well as universally employed in religious activity. Indeed, it has been proposed that the ‘God Spot’ of the brain can be stimulated into activity by waves of sound. Canadian neuroscientist Michael Persinger of Lautentain University has managed to reproduce such feelings in otherwise unreligious people. According to Persinger:

‘Typical people report a presence. One time we had a strobe light going and this individual actually saw Christ in the strobe… (another) individual experienced God visiting her. When we looked at her EEG (electroencephalogram) there was this massive spike and slow-wave seizure over the temporal lobe at the precise time of her experience – the other parts of her brain were normal.’1Ian Cotton ‘Dr Persinger’s God Machine, Independent on Sunday, 2 July 1995

So, the beat goes on. And it’s clear, if only through its ubiquity, that rhythm is a powerful and versatile tool for artists of all kinds. But to understand how this relates to the visual arts, it’s necessary to understand what we mean by rhythm. And crucially, the distinction between rhythm and repetition.

Generally speaking, there are five types of rhythm.

Regular Rhythm – Like a pulse, a regular rhythm follows the same intervals over and over again. And like a beating heart, it’s reassuring. It’s the grid or metric that establishes the rules of a composition.

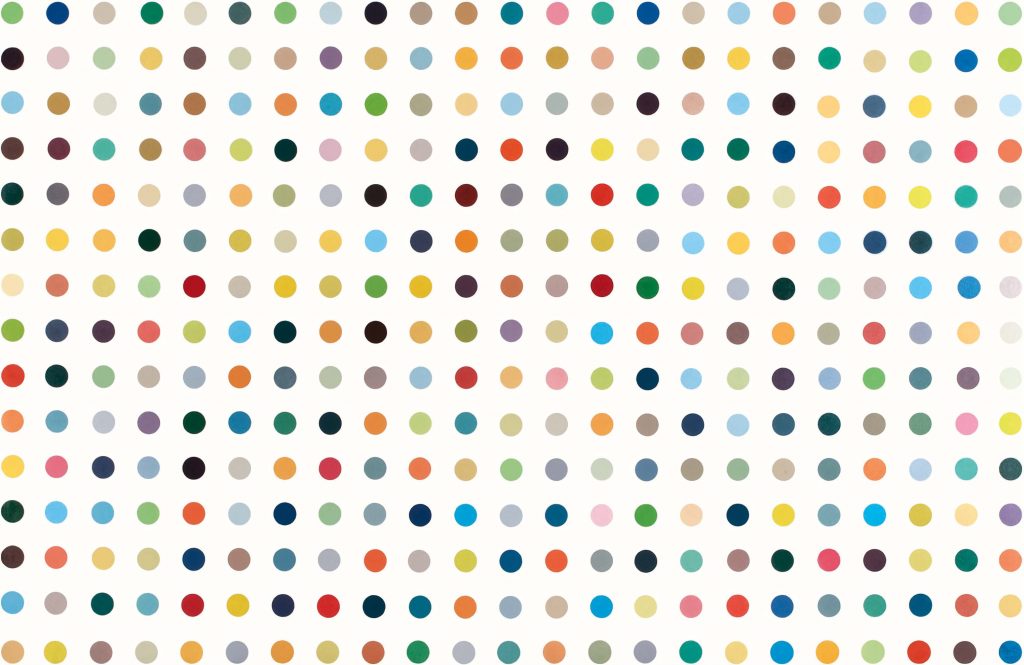

Damien Hirst, in his ‘Spot’ series, creates a repeatable, predictable mesh of equidistant and equal sized units of colour. The metronomic beat removes uncertainty. The eye can relax and wash across the surface in a cadence that is both prescribed and open. Like the dancer to an electronic beat, it provides momentum without compulsion. With the requirement of novelty removed, tiny variations assume significance. It encourages a meditative state, meshing with the alpha-frequency waves the brain generates as it enters a conscious state of relaxed, receptive awareness.

‘It isn’t necessary for a work to have a lot of things to look at, to compare, to analyze one by one, to contemplate. The thing as a whole, its quality as a whole, is what is interesting. The main things are alone and are more intense, clear and powerful.’2Donald Judd, from ‘Specific Objects’, essay first published in ‘Arts Yearbook’, 1965

But any perfection can quickly turn monotonous. Worse, it becomes a neurological prison – the insufferable insistence of the dripping tap. The bricks of the prison cell. Sometimes, perhaps, this is the point. Minimalism for many of its exponents was a reaction to the tyranny of emotion. An unadulterated, regular and predictable repetition was the key to revealing a cleaner, purer interaction with the material world.

Which is why we also need Random Rhythm.

Random rhythm is the disruptor. Repeating elements with no specific regular interval: falling snow, pebbles on a beach, the flow of traffic along a road. Because the brain is designed to detect patterns, the cognitive dissonance that constant interruption of predictability creates forces us to look. We seem to be looking for confirmation that there is a regular rhythm at work, if only we can understand it. At the same time, the continual disruption drives the fascination.

It’s also worth noting that a rhythm may appear random if you examine a small section. But if you step back and look at the bigger picture it may be there is a regular but complex rhythm overall. In music it is the pauses that create the arhythmia. It is the spaces between the elements that create the possibilities.

In painting, Jackson Pollock. His art remains the lodestone for a structure that appears random up close, but viewed holistically reveals a metronomic regularity that reflects the physical work of its making.

The beat of his paintings come from the exertions of making them. The beat is corporeal – they are records of a body in motion. And because we all have bodies, the rhythms of exertion are a language we can all speak. These are organic, visceral, chemical responses, broadly beyond our conscious control. Hence their power. But surely we’re more than that? Are we not sentient animals? There must be more to art and creativity than simply responding to the biological qualities we share with every other living creature.

Which is why we need Alternating rhythms.

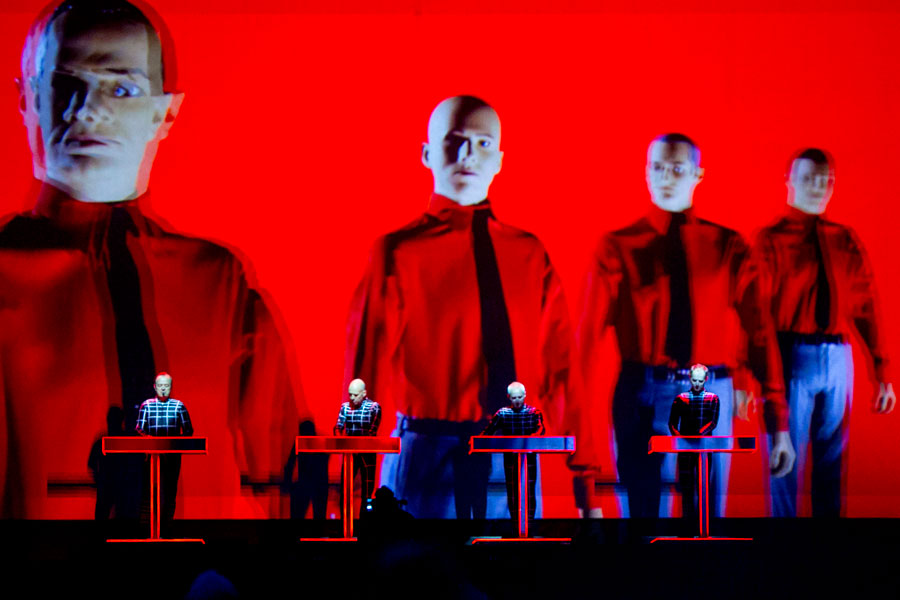

At the Design Museum, Kraftwerk, the German godfathers of electronica, loom large. That’s justified. Their 1981 album, ‘Computer Love’, focused on the increasingly influential role of computing in modern life. Forty years later it’s difficult to argue. The lyrics explore a wide range of themes related to technology, from government data collection to the growing isolation in a supposedly interconnected technological world. With untouchably dry Teutonic irony, the album appears to celebrate the infinite possibilities that computing power will bring:

‘I program my home computer

Beam myself into the future.’

But alongside that ambitious vision, there’s also an understanding of the craft skills essentially to any creative acts – the tools and techniques of the artist.

‘I’m the operator

With my pocket calculator

I’m the operator

With my pocket calculator

I am adding

And subtracting

I’m controlling

And composing’

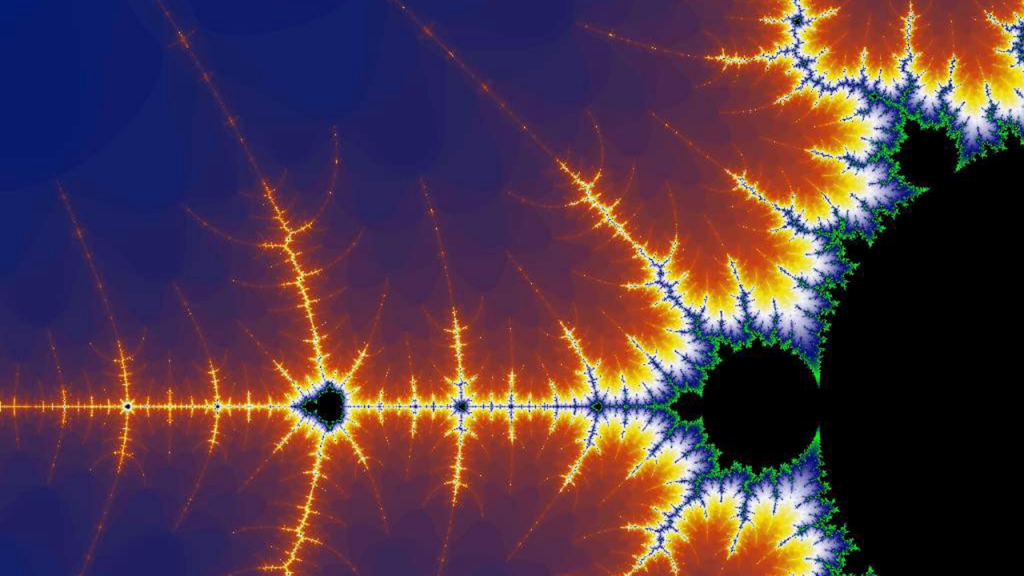

For an Alternating Rhythm to retain its structure and not become a Random Rhythm, you need maths. And one thing computers are very good at is maths. Fractals, once a mainstay of any rave’s lighting and projection show, are a good example. The term ‘fractal’ was first used by mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot in 1975, the same year Kraftwerk released their first entirely electronic album, ‘RadioActivity’.

Mandelbrot based it on the Latin ‘fractus‘, meaning ‘broken’ or ‘fractured’, and used it to extend the concept of theoretical fractional dimensions to patterns in nature.

Again, not a new idea. Much Islamic geometric art uses similar mathematical principles. Designs build up, overlapping and interlacing, with a wide variety of tessellations and semi-repetitions. In Islamic culture, the patterns are believed to lead the viewer to an ‘understanding of the underlying reality, rather than being mere decoration…’3https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keith_Critchlow It’s another indication that the deeper purpose of rhythm has always been to help the viewer open a door into a non-figurative, non-physical world. A realm more of the spirit than the senses.

Today, the computing power we have is exponentially greater than anything the Moorish palace builders had to play with. However, it seems that artists continue to use it towards the same end.

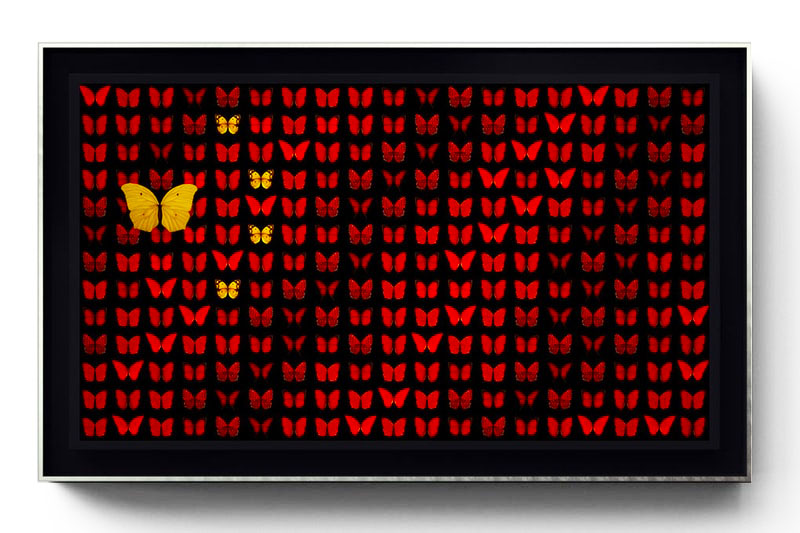

The digital artist Dominic Harris works on the porous borders of technology and aesthetics.

A piece like ‘World Stage’ consists of ‘code, electronics, 4K touch display, sensors, aluminium.’ But those are just the components. The actual experience of the work is a subtle but complex matrix of alternating rhythms. A regular rhythmic grid of identical butterflies is interrupted by the viewers touch or gestures. Slowly, confirming to rules set in the software VVV, the butterflies begin to move and morph. The patterns break and reassemble. Nothing stays still yet nothing moves out of sync. The unity of the work is preserved by the sense of an underlying rhythm despite the seemingly random movement of individual elements. The effect is simultaneously mesmeric and energising, and begins to describe the fourth category of rhythm: the Flowing Rhythm.

One of the fundamental, but baffling, qualities of quantum physics is the principle that a particle can exist in more than one place at a time. And rather than describe any single unit as a discreet entity that exists in one place at one time, rather it will function more like a wave or a vector. Of course, anyone who has ever picked up a pencil, sharpened it to a fine point then drawn a long, smooth line across a flat piece of paper will understand this intuitively. Artists have got quantum for a long time.

The basis of analytical cubism is that an object in space will be observed from many different angles. Therefore, to create an accurate depiction of that object, multiple aspects must be displayed simultaneously.

And this principle is displayed elegantly at the Design Museum show through a light installation by 1024 Architecture – a Paris-based collective, self-described thusly:

1024 = 210

1024 is a recurrent number in computer science.

1024 is a screen resolution.

1024 bytes = 1 Kilobyte.

1024 is a creative studio.

‘CORE’, their collaboration with DJ Laurent Garnier, uses LED lights (each one a single unit) mounted onto a grid of poles which together create waves of light and colour that echo the beats and pitches of the music.

Sometimes it’s surprising how well artists can bring to life principles that scientists struggle to explain, and the secret seems to be combining apparently distinct disciplines or methods into a synaesthetic experience. And while artists like Kandinsky naturally combined music with mark-making, the introduction of logical code languages is spawning a whole new way of seeing the world all the way down to its sub-atomic components.

But ultimately, any connoisseur of electronic music will remind you that the 5th category of rhythm is perhaps the most important. We discussed how rhythm is how we make sense of time on a human level. The beats that measure every moment and can stretch or shrink to cover the entirety of human experience. And part of life is growth. The sense of progress, of movement towards something. The essential conviction that this is all leading to something, not matter how ill-defined that destination may be, at least there is change and therefore hope.

This is Progressive rhythm. – We make a progressive rhythm by changing one characteristic of a motif as we repeat it. DNA dances to the beat of a progressive rhythm, with tiny changes dropped into each generation, slowly refining and adapting the species as a whole. Progressive rhythms are within us and surround us. And they manifest themselves aesthetically in electronic music, often through the intercession of the DJ, whose job is to build, manage and maintain the energy on the dancefloor by creating a rhythm that goes somewhere. Perhaps the closest analogy to this principle is to be found in Generative Art.

In 1988 Henry Clauser defined this practice as ‘(in)… the evolution of generative art that process (or structuring) and change (or transformation) are among its most definitive features, and that these features and the very term ‘generative’ imply dynamic development and motion. … (the result) is not a creation by the artist but rather the product of the generative process – a self-precipitating structure’4Clauser, H. R. Towards a Dynamic, Generative Computer Art, Leonardo, 21(2), 1988.

At the same time Brian Eno was exploring ‘self-precipitating’ musical forms in his ‘Ambient’ series. But if you’re really interested in exploring progressive rhythms, you’ll need to leave the dance floor and eschew the gallery space. Because the truest, most ambitious expression of generative art is a game. In ‘No Man’s Sky’, ‘Every player starts on a different planet near the edge of effectively the same galaxy, generated in the same way from the same seed, but with apparently no substantial multiplayer overlap, no chance to meet. Because the galaxy is generated rather than designed, your starting planet might be hot or cold or toxic or radioactive, populated by trees or cacti or twisted vines, tinged red or yellow or green or brown or blue.’5https://www.theguardian.com/games/2019/sep/12/no-mans-sky-beyond-a-childhood-fantasy-realised

‘No Man’s Sky’, and other similar immersive and interactive experiences use the power of computing to imagine and create. And uncomfortable as that may feel, in essence it’s no different from the sharpened graphite stick that sketches a simulacrum of a face or a landscape. The intention is exploration, but rhythm is the vehicle.

‘Electronica: From Kraftwerk to the Chemical Brothers’ is a life-affirming experience. It’s a celebration of what is peculiar about our species – our ability to inhabit and explore the twin aspects of our nature; the Apollonian capacity for reason and the Dionysian appetite for freedom from that reason. From Kraftwerk’s deliberately hygienic celebration of machine-led modernity to the sweaty ecstasies celebrated by the Chemical Brothers. The mathematically precise to the emotionally messy with no contradictions, no grinding of gears between the two states of mind.

Or as the singer Pink puts it more concisely:

‘If God is the DJ, then Life is the dance floor; Love is the rhythm and You are the music.’