Matt Dennis: ‘Red is always Good. Red is better than Brown. And Green is not always Great.’

‘The art world is capricious. It’s not clear what the reasons are for some artists losing traction, and others sailing into the sky.’

Stefan Edlis, Art Collector

‘The Price of Everything’, Nathan Kahn’s documentary on the Contemporary Art market, begins wordlessly, the camera following a platoon of Sotheby’s art handlers as they make trolley-loads of big-name Modern and Contemporary paintings (Stella, Noland, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Richter, et al.,) ready for their moment of reckoning in the cavernous Manhattan auction hall. Straight away, the thought intrudes: how suddenly and irrevocably the ‘now’ this film purports to capture- it was made, and first shown, in 2018- has become ‘back then’; back then when the notion of ‘handling’ anything other hands had touched didn’t seem like an act of suicidal recklessness; back then when scenes of people in disposable gloves pushing trolleys didn’t immediately summon up harrowing visions of the Intensive Care Unit. These two-year-old scenes feel far, far distant from our new ‘now’; they already look like history. Which is not to say, however, that there isn’t a great deal in the film’s hour and a half that speaks directly to our current condition; in particular, the sheer precariousness of the world it explores, and the sense of impending calamity that seems to hover in the air around its participants, best expressed in the words of art dealer Gavin Brown: ‘Everybody knows we are careering towards some edge or some end. I think I smell smoke…’

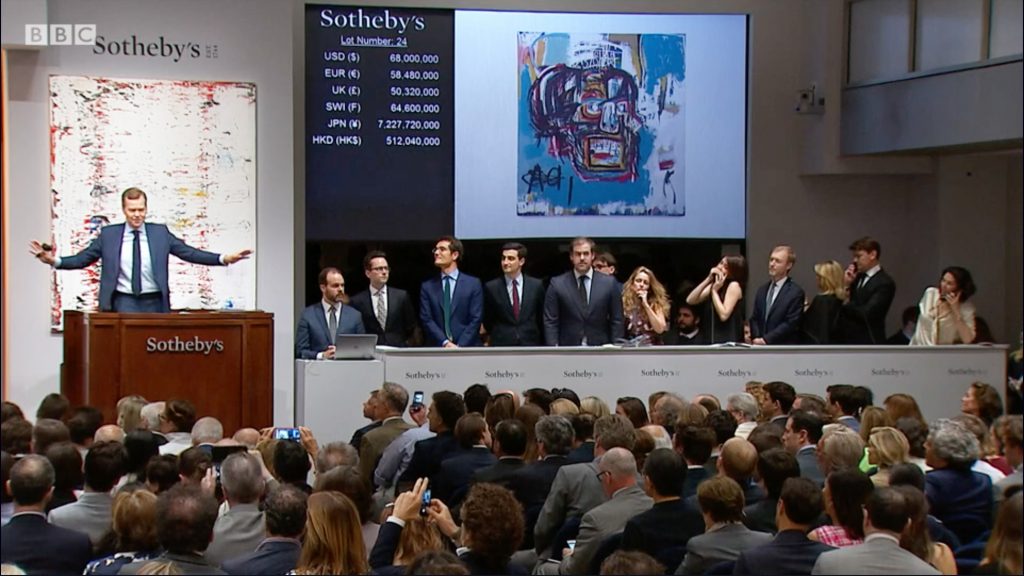

Kahn’s film is loosely structured, impressionistic, frequently hilarious, often doubling back on itself, dispensing with strict chronology, choosing instead to circle around its ostensible subject- ‘The Triumph of Painting’, the 2016 auction at Sotheby’s New York of ‘big-ticket’ paintings and sculptures from the Stephen and Ann Ames collection- and even, for long stretches, forgetting about it altogether. There’s a big, loud, and obvious ninety-minute story to be told here, with a big finish, in which we watch the posh tuxedoed Brit at the podium work the packed auction room in a flurry of jump-cuts from one astonishing hammer-price to the next, all the way to the shuddering climax of an eye-watering ninety-eight million dollars for a Jean-Michel Basquiat; but happily, Kahn appears to have no interest in telling it. He gets the orgiastic auction scene out of the way in the film’s first three minutes, thereby freeing himself to roam back and forth in the hunt for richer pickings amid what one of the art dealers he encounters at New York’s Frieze Art Fair describes as ‘the higher reaches of the treetops’- the penthouses of Park Avenue and beyond- and here, Kahn plies his camera and microphone like an art-world Attenborough, getting as near as he dares to the UHNWI (that’s Ultra-High Net Worth Individual, in case you were wondering) in its natural habitat.

Why editorialise, why strain after a story, when it seems that all Kahn has to do is part the foliage, point the camera, and let one of the extraordinary denizens of the treetops do the job for him? Stefan Edlis is a hugely wealthy- and on the evidence of his performance in the film, hugely entertaining and hugely likeable- ninety-two-year-old, who describes himself as ‘the schmuck who overpaid on an overpainted Mondrian’, an act which nevertheless ‘put (him) on the map’ as he started out in collecting art in the 1980s. Now, with his penthouse crammed to the rafters with Rauschenbergs, Warhols, Polkes, and a Jeff Koons ‘Bunny’ (a cast in silver of a balloon animal whose value, aptly, has ballooned from the $945,000 Edlis paid for it to an estimated $65 million) he’s deemed powerful enough, and knowledgeable enough, to have the whole market pay attention to the choices he makes; and hence, enough of a player to merit a home visit from Amy Cappellazzo, Sotheby’s New York’s ‘Rainmaker’, whose job it is to drum up interest in the impending Ames sale. By this point, we’ve already started to get the sense of obscure laws operating, as we learn of Edlis’s self-imposed ‘parameters’ for the size and composition of his holdings, – ‘two hundred works, forty artists’– and of the advice he followed in making individual purchases, such as the painting he acquired from Warhol’s ‘Skull’ series: in whichever of the available versions he chose, he understood that the green acrylic slopped around the silkscreened skull ‘had to be juicy’, and the pink laid in beneath it ‘had to create a baby face.’ And if you’ve ever wondered what sort of unwritten rules govern the buying and selling of Contemporary Art at this level, the scene between them on Edlis’s sofa will help clarify:

Edlis: ‘Red is always good. Red is better than brown. Brown pictures are unsellable. And don’t buy any pictures with fish.’

Cappellazzo: ‘Brown is hard. And green is not always great.’

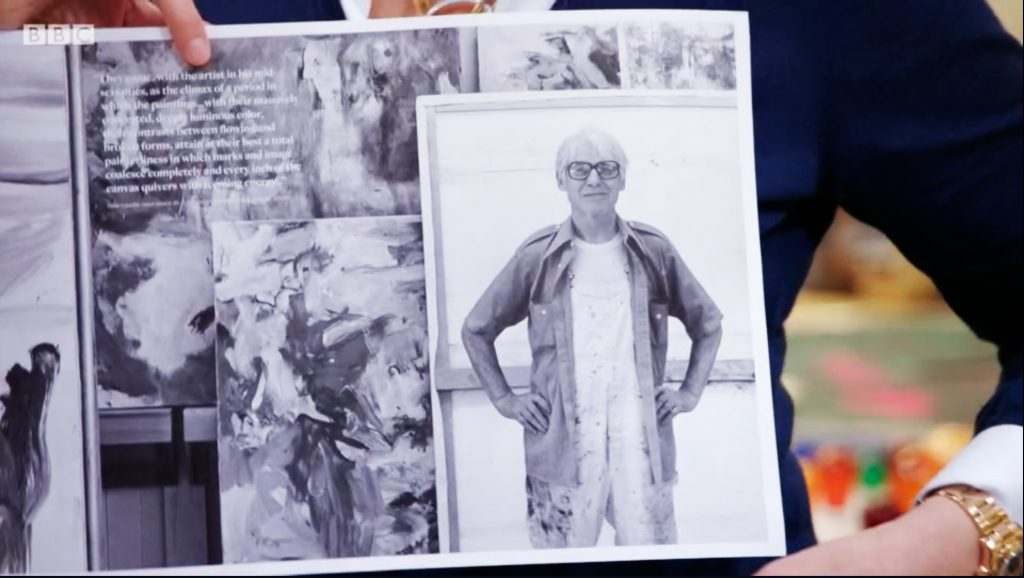

Follow all that so far? Well, pay attention, because there’s more: back at Sotheby’s, down in the stockroom with the proofs for the Ames sale catalogue, Cappellazzo is at pains to emphasise that ‘you gotta do your comps.’ In other words, draw the sorts of visual comparisons, in the catalogue spreads, that will boost the aura of art-historical significance around artist and work. Why, look, here’s a shot of De Kooning in the studio, standing right next to the very painting of his that’s going to be sold: that, we gather, is ‘the Holy Grail of comps’, to be able to show creator and creation with umbilical cord intact. George Condo, who’s also got work in the sale, is ‘a darling of the market’, but hasn’t yet quite attained De Kooning-level renown in some quarters; and so, just in case there are still any well-heeled individuals out there who might hesitate to bid on his paintings on the grounds of uncertainty as to his bona fides, a deftly juxtaposed masterpiece by one of the undisputed heavy-hitters of Modern Art should help settle the matter in his favour. And since Condo is ‘a super-disciple of Picasso’, there it is: Picasso’s ‘Seated Woman’ of 1927, comping the living daylights out of the Condo canvas, bathing it in its radiance.

Cappellazzo, like Edlis, is good value, but tightly-wound and defensive where he is jovial and self-deprecating. Sizing up the merchandise, she speaks in an affectedly casual, clipped jargon that every so often seems to yield a weird poetry all its own: as she sifts through the proofs of the catalogue spreads, she suddenly unearths an image of Matisse’s ‘Bonheur de Vivre’- obligingly doing its bit to provide ‘comps’ for something else in the sale- and Kahn asks, what would that go for in the current market? ‘Forget about it’. And when he presses her: ‘Coupla hundo’. What, two hundred million dollars? ‘Yep’.

Which only makes one wish that Kahn had got round to asking her: might a Condo ever fetch a hundo? Given the way his prices have been steadily rising, one can’t help but wondo…

If ‘The Price of Everything’ was a painting, it would probably look like one of the big Gerhard Richter abstracts destined for the Ames auction: big, brightly-coloured, with some sections laid in with a pretty broad brush,1Such as our encounter with collector Inga Rubenstein, who disintegrates on-camera into lip-trembling, hand-fanning tearfulness as she recalls her first encounter with the Damien Hirst butterfly painting her husband bought her for a birthday present: ‘it was just sooo beautiful…’some rendered indistinct by motion blur, as the camera sweeps and swoops through art fairs, show openings, and auction rooms; and some shifting abruptly into sharp, lingering focus, revealing a wealth of vivid detail. Most vivid of all, the documentary-maker’s dream of a double act that lends shape to Kahn’s sprawling, sly film: Poons and Koons.

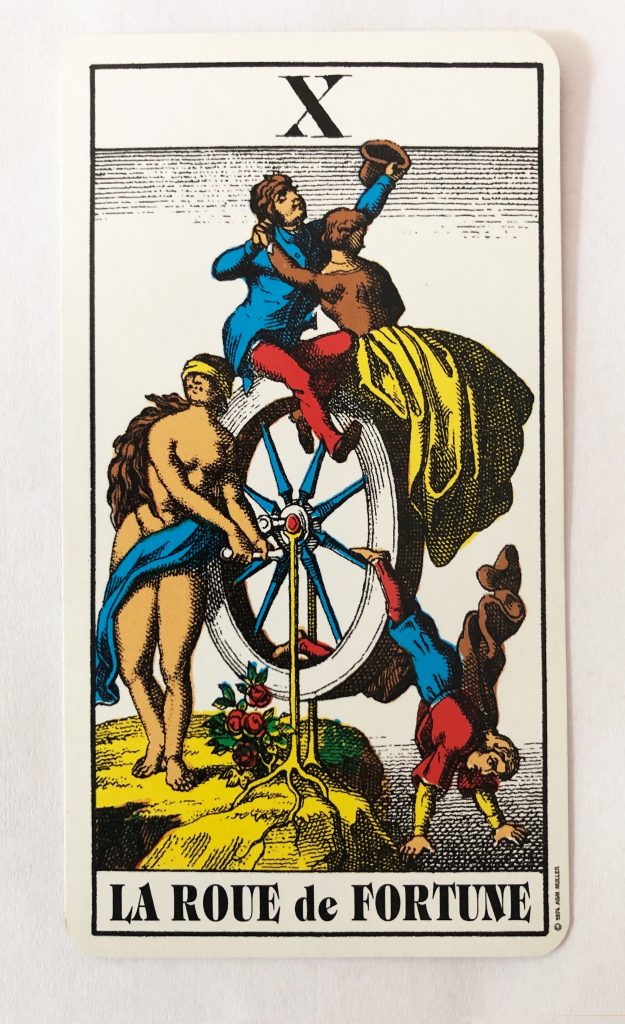

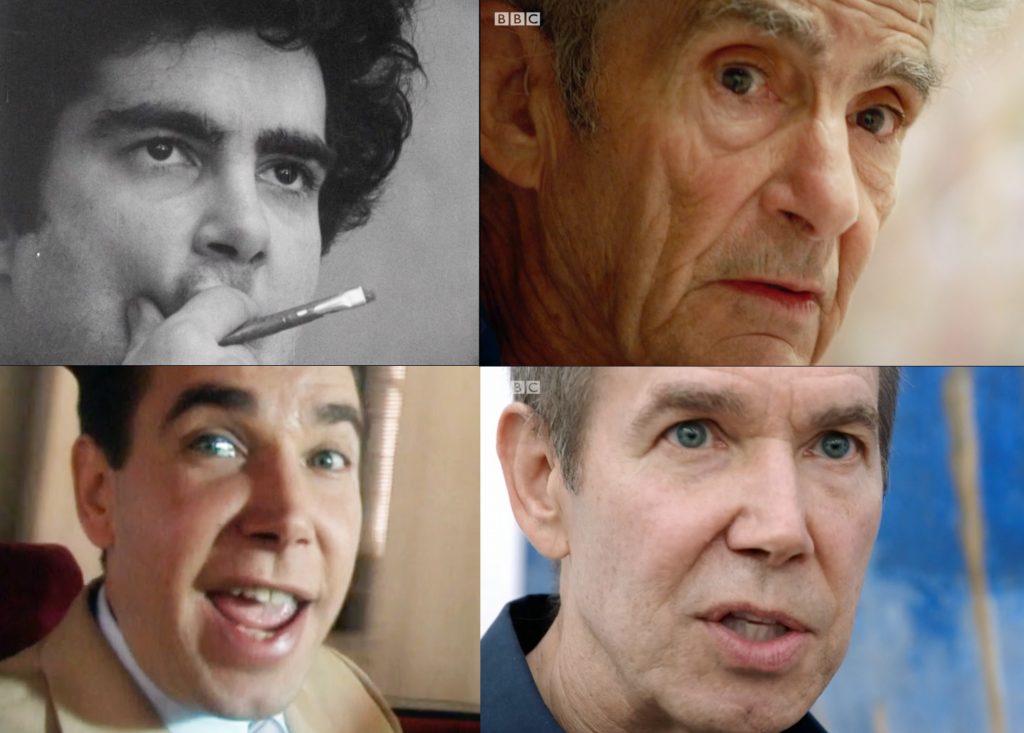

It’s now half a century since Larry Poons’ effortlessly cool turn in Emile de Antonio’s era-defining documentary ‘Painters Painting’, chubby-faced and cherubic in a bespattered boiler suit, smoking, pouring paint, and pouring scorn on collector Robert Scull for what he saw as the latter’s self-aggrandising assertion that it was his early patronage that had allowed Poons to quit his job as a short-order cook and concentrate on his painting; and judging by the somewhat battered, weather-beaten condition of his house and studio in upstate New York (and, it has to be said, of the man himself), it’s fairly safe to say that avoiding the cloying attentions of Scull and his ilk is not a problem Poons has often had to contend with in the intervening decades. He appeared in de Antonio’s film because back in 1971 the director deemed him a ‘name’ of near-equivalent standing to Noland, Olitski, Stella, and the other abstractionists that featured in it; this time round, he’s clearly here for very different reasons: one of them being, to mark the lower limit of a scale that the market uses to measure artists in blunt, bankable terms. ‘The Price of Everything’ roams up and down this scale, enjoying itself hugely as it does so: we meet painters Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Marilyn Minter, both near the low end, but rising steadily towards auction results around the million-dollar mark; Condo, sitting pretty in the multi-million middle register; and Basquiat, returning from the great beyond via archive footage and his friend Condo’s reminiscences, who manages to be off the top of the scale altogether, fetching down the sorts of prices that only come with making an early exit that shuts off the supply of new work for good; but it’s the juxtaposition of Poons, a painter who in critic Barbara Rose’s words ‘has the capacity to destroy his market constantly, and is a genius at it’ with Koons, the priciest artist alive, that lifts the film to the level of an art world parable, a cautionary tale, a live-action enactment of the Tarot card that depicts the blindfolded goddess, Fortuna, cranking the wheel, sending one lucky soul skywards whilst another plummets.

Kahn has struck documentary gold with these two, and he knows it. The camera lingers lovingly over each glaring contrast, switching between the ordered, gleaming cleanliness, tidy workstations, and hushed industriousness of Koons’ vast studio, as his team of assistants get their heads down, laying out hundreds of number-coded dabs of pigment on gridded pallettes, deploying a fantastically painstaking array of masking and stencilling techniques to precisely recreate every tiny nuance of colour and texture in the scaled-up Titian, Giorgione, and Courbet copies they’re making2For a succinct evaluation of these ‘Gazing Ball’ paintings, look no further than the Instantloveland archive for Matthew Maxwell’s excellent essay on Koons’ Ashmolean Museum show, ‘Loving the Low Brow’:https://instantloveland.com/wp/2019/05/12/matthew-maxwell-on-jeff-koons-at-the-ashmolean-loving-the-low-brow/; and Poons’ walk across his weed-choked lawn in encrusted overalls, past the tumbledown summerhouse, to the coagulated clutter of his ramshackle barn workspace, where the best part of an entire roll of canvas hangs unstretched in one continuous curtain off three of the four walls, flapping and buckling as he pushes and prods at it with brush and fingers, laying the colour on in smears and scribbles.

The passage of time has clearly done nothing to mitigate the combative spikiness of the young Poons, as seen and heard in de Antonio’s documentary; the then thirty-four-year-old painter’s laconic, straight-shootin’, tell-it-like-it-is verbal delivery is still very much in evidence, in response to the hard knocks dished out to him by fickle fate: ‘They all thought I was dead. That’s not my fault.’ Koons, meanwhile, is neat and preppy in shirtsleeves, and as forthcoming and engaging as Poons is guarded and vigilant, radiating wide-eyed enthusiasm in place of Poons’ haunted thousand-yard stare, bursting with gee-whizz keenness to share with us the thinking that informs his sculpture. We hear about Koons’ proposal for a site-specific work in Sweden, which will involve the suspension, from a crane, of a working steam locomotive, and he’s kind enough to act out the movements with both arms as he describes how the work functions: ‘It’s like a human being, with the pistons going in and out, like breathing in and out, it’s a metaphor; it goes faster and faster, woo-woo, woo-woo, woo-woo!’

Poons, on the other hand, is less inclined to offer up analysis of how his or anyone else’s work might progress, or indeed, to endorse the idea that it might be possible to plan for a particular outcome at all: ‘Art doesn’t give a shit; it never has.’

Whenever he’s had a chance, over the years, to deliver his polished patter to camera, there’s always been a whiff of sci-fi otherworldliness beneath what critic Jeffrey Deitch describes here as Koons’ ‘natural American salesmanship’, as if he’d just emerged fully-grown from a giant seed pod down in the basement; and interestingly, art historian Alexander Nemerov, who appears in the film as dour naysayer to Amy Cappellazzo’s bright cheerleader, also reaches for a fantasy metaphor in describing his encounter with a Koons sculpture- ‘Like Jason and his Argonauts in a Ray Harryhausen animated sequence, confronting a mythical beast they have to slay’. Now, though, Kahn finds Koons pushing a new and far more uplifting narrative. Pausing in front of one of his ‘Gazing Ball’ works, Koons explains how the blue glass ball affixed to the painting functions as a kind of inter-dimensional portal: ‘You go into the realm of the eternal; there’s this connectivity with the past. It’s telling you everything it can about where you are in the universe, right at this moment.’

And where is Koons in the universe, right at this moment? Pretty much everywhere, it turns out. He has matured, we understand, into a sort of Jedi Knight of Contemporary Art, in a state of mystic harmony with its cosmos, channelling its invisible market energies via his work: in fact, so total is his identification with it, that to a large extent, he has become the market. You don’t get to invoice a Swedish patron to the tune of fifty million dollars for hanging a train from a crane unless you’re one of a select few that the astonishing sums of money sloshing around the art market tend to flow towards. In her study of the coming-together of art and money, ‘Dark Side of the Boom’, Georgina Adam stresses how few artists- Koons being one- carry the market between them: ‘Research carried out by Artnet magazine in 2017 confirmed this concentration on a few artists. It found that just 25 artists were responsible for 44.9% of all post-war and contemporary art auction sales in the first half of the year.’3Adam, G., ‘Dark Side of the Boom’, Lund Humphries, 2017

As Darth Vader might very plausibly have said, the market forces are strong with this one…

‘Deep down, you have to be shallow.’

Stefan Edlis

‘The Price of Everything’ is going with breadth, not depth, roaming freely over the art market’s bright surfaces, not dawdling over them too long, or delving too far beneath. And yet it still manages, in its playful fashion, to nudge us in the direction of answers to the questions it poses; even throwing in a moral, for good measure…

Why has the market said ‘Yes’ to Koons so spectacularly, whilst dealing Poons a flat ‘No’? Any number of reasons; but to a significant degree, it can be argued, because of the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’, respectively, that Koons and Poons have said to it. Koons’ ‘Yes’ to the market is implicit in the comfortable, snug fit his work makes with the aspirations of the UHNWIs on the long waiting list to buy. Alexander Nemerov says of Koons’ ‘Diamond’: ‘Its perfection is what I resist’; but that same perfection is precisely the quality that flatters Koons’ customers, and draws them in: the immaculately vacant mirror surfaces of the work reflect back to him or her whatever perceptions they have unwittingly brought with them to the encounter, thereby persuading them that they have the sensitivity, the depth of feeling, the connoisseurship to have experienced those perceptions, not within themselves, but rather, within a work of art. Poons’ ‘No’ is embedded in the turgid, laboured surfaces of his paintings, in his lack of appetite for making art that meets the market half-way; and also in his lack of interest in being Poons at all: we hear how, at the height of his success of the late 1960s, he confessed his anxieties about the paintings he was making to a fellow artist, who replied: ‘You don’t have to worry; you’re Poons.’ To be known for one way of working; to have become, in effect, a brand name, ‘Larry Poons’; this prospect, we learn, disgusted him. Koons’ Louis Vuitton handbags, meanwhile, with their Old Master imagery overlaid by ‘LV/JK’ double monogrammes, modestly priced at $4,000, have apparently been flying off the shelves.4 Jonathan Jones, in The Guardian, described them as ‘a joyous art history lesson’. Good to know that art criticism still thrives in these troubled times….

In his truly wonderful essay, ‘On Bullshit‘,5Frankfurt, H.G., ‘On Bullshit’, Princeton University Press, 2005 philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt attempts ‘to articulate, more or less sketchily, the structure of its concept’; The defining characteristic of bullshit, according to Frankfurt, is its total lack of connection with a concern for the truth: ‘the fact about themselves that bullshitters hide…is that the truth-values of their statements are of no central interest to them.’ In developing his line of argument, he takes aim at what he sees as the widespread misconception that bullshit, of its very nature, must be slovenly, ill-conceived, and poorly executed:

‘The notion of carefully wrought bullshit, (with) thoughtful attention to detail, requir(ing) discipline and objectivity, (and) standards and limitations that forbid the indulgence of impulse or whim…strikes us as inapposite. But in fact it is not out of the question at all’; and Frankfurt is insistent that the realms of advertising, public relations and politics are replete with instances of just this sort of bullshit, in which ‘exquisitely sophisticated craftspeople’, utilising ‘advanced and demanding techniques…dedicate themselves tirelessly to getting every…image they produce exactly right.’

It’s uncanny: word for word, he could be describing the Koons atelier there. Unless we’re persuaded of the ‘truth-value’ of Koons’ assertion that the work coming off its busy production line really will take us ‘into the realm of the eternal’ we have to concede that it is, by Frankfurt’s yardstick, a bustling sweatshop devoted to production of the thick brown stuff. The machine-tooled perfection of its output tallies neatly with the market’s love for the definitive, for the measurable, for the matter-of-factness of the balance sheet; and with the sweeping certainties the market trades in, packaged up into little discrete units of consumer-friendly judgement. Cue Amy Cappellazzo: ‘Richter’s just got it.’

It’s here that ‘The Price of Everything’ excels, in capturing the edginess, the jitteriness beneath the bright, taut bonhomie of the film’s cast of critics, curators, collectors, rainmakers, and feinschmeckers;6Isn’t that a great word? Edlis uses it: it’s the German equivalent of ‘connoisseur’ the sense of a self-policing consensus, watching warily for the slightest deviation from correct protocol. The possibility that Richter might be a very uneven artist indeed; that Basquiat’s paintings might be the work of a so-so illustrator, blown up big and tarted up with ‘expressive’ handling; and that the only way in which George Condo might be a ‘super-disciple of Picasso’ is in much the same way that Shakin’ Stevens was a ‘super-disciple’ of Elvis Presley- namely, a few borrowed moves, and precious little else; speculations like these are the product of the sort of sceptical, discursive mindset whose time, the market would have us believe, is long gone, and good riddance; all it brought us was the likes of Poons, and his inexplicable lurch away from winning ways with a market-friendly formula of grids and dots into all manner of misadventures in thick impasto…

In their place we have the glazed perfection of the Koons sales pitch: and backing it up, underwriting its promise, we have Koons himself, the living, breathing corollary of the propositions put forward by the work; open, transparently self-aware, and tangibly sincere.

Of this sort of use of the self as guarantor, Frankfurt has this to say:

‘There is nothing in theory, and certainly nothing in experience, to support the extraordinary judgement that it is the truth about him or herself that is the easiest for a person to know…our natures are, indeed, elusively insubstantial- notoriously less stable and less inherent than the natures of other things. And insofar as this is the case, sincerity itself is bullshit.’

And the moral? Well, Fortuna just keeps on turning that wheel…

Towards the end of ‘The Price of Everything’, the mood of its Poons sequences seems to brighten and lift out of its mournful minor key; the lonely tableaux of the painter toiling away in his barn, small and almost lost amid a vast acreage of hanging canvas, interspersed with a chorus of voices (Barbara Rose, Stefan Edlis, Mary Boone) wondering what the hell had happened to him, give way to frenetic group scenes between artist, dealer, and black-clad art-handlers, cutting, cropping, considering, and then choosing which parts of his colossal unspooling mural will be mounted onto long landscape-format stretchers, ready for inclusion in ‘Momentum’, Poons’ show at the Yares Gallery; and we understand that finally, after the best part of a half-century in the wilderness, and for reasons that, given the incomprehensible mood-swings of the market, will have to remain obscure, the long-lost prodigal will be welcomed back into the tender clutches of the Contemporary Art scene.

And as for Koons: it would take a heart of stone not to enjoy the irony of an artist who intends to hoist a train being hoisted, in turn, on his own metaphor. The locomotive, with the pistons going in and out, going faster and faster, may work well, as he suggests, in standing in for a human subject; but it’s also a perfect image of Koons’ career, with its irresistible forward momentum, smashing through all previous auction-price records, pulling the art market along behind it. Sooner or later, though, with every speeding locomotive, there comes a point at which the steam runs out, and the end of the line is reached. So what will be the final destination for the Koons Express?

A lobby, apparently. As we learn from Stefan Edlis’ conversation with Amy Cappellazzo as they leaf through the catalogue of a previous Sotheby’s sale, Koons’ sculptures have started to become the art of choice for the vast courtyards and atriums in the commercial spaces of high-end real estate. Goodbye, then, to the inestimably precious aura of rarefied, refined, exclusive and daring taste that ownership of a Jeff Koons work has always been understood to bestow upon those wealthy enough to acquire one…

Edlis: ‘The real estate people started thinking of Koons as ‘Lobby Art’’.

Cappellazzo: ‘It’s gonna hurt him. ‘Lobby art’- it’s the kiss of death. Once you’re in the lobby, you never get out.’

5 thoughts on “Matt Dennis: ‘Red is always Good. Red is better than Brown. And Green is not always Great.’”

Comments are closed.

Great to see Larry Poons, looking like the real thing. He is no young man, but so exciting to see proper painting. Not sure about the rest…

Mr Dennis, in this excellent review, does not touch upon the reasons why Larry Poons lost his appeal after he moved on from his optically dancing discs paintings which had brought him fame and fortune.

The elderly collector, Mr Stefan Edlis, says ‘it is not clear what the reasons are for some artists losing traction, and others sailing into the sky’.

In the later 1960’s Clement Greenberg had encouraged Poons, who became friends with artists Greenberg liked. He changed his working methods and the result was the ‘large disc’ paintings where the whole surface is alive from the artist’s touch. These were not so popular as the optical ones.

In 1974, during my first visit to New York, the influence of Greenberg had reached its zenith and was waning. There were complaints about ‘The Gang’, meaning his circle of friends and their perceived power. ‘If Clement Greenberg likes your work it’s the kiss of death’, I remember hearing.

This might help to answer some of the questions asked by that senior collector and many others who follow contemporary art.

What a difference a letter makes: Koons to Poons. Interesting writing, but I’m not sure that Poons is quite the antidote; though I’m not suggesting that you entirely think he is. Process art: unroll and cut up?

Oh, the problems the rarified collectors have in deciding how they can become a part of history. Fortunately the rest of us can look and make our own minds up, just for the experience of looking. Not being startruck is a good starting point.

Leaving aside Pete’s concerns about Poon’s art, isn’t the problem with him as an antidote to Koons precisely that it is just one letter change: from one singular artist to another. To me – although generationally I’m well after Koons and not just Poons – what is worth mourning is not a singular artist thrown out by the market, but a lost ecosystem, an exchange of images and ideas about art, of which Poons was just a part?