Charley Peters on ‘Lee Krasner: Living Colour’: Dead Husbands, Other Stories, Go Girlfriend!

In the second of her texts as a Writer-in-Residence for Instantloveland, Charley Peters hosts a discussion with artists Alison Goodyear, Clare Price and EC about the exhibition ‘Lee Krasner: Living Colour’.

Alison Goodyear’s paintings explore the possibilities of how an artwork might intervene in the ‘normal’ regime of vision, whilst questioning the substance of paint and process. She has recently started speculative work painting in Virtual Reality. Clare Price is an abstract painter with an online photographic aspect to her practice that spills into both writing and performance. EC brings together disparate painted elements in her work, repeatedly reassembling discarded matter from the studio into oppositional, material compositions.

Charley: We all recently saw ‘Lee Krasner: Living Colour’ at Barbican Art Gallery, and it feels like there’s lots we can talk about in relation to her extensive breadth as an artist, and also, regrettably perhaps, around other aspects of Krasner’s presentation in the exhibition, and in art history in general. It feels to me that we don’t know her work well enough; this is the first major European survey of her work in over 50 years, and there is only one work by Krasner in a UK public collection, ‘Gothic Landscape’ (1961) held by the Tate. There are other reasons why we haven’t got to know her work too, and these are just as frustrating as the lack of wall space given to Krasner’s work in this country. I originally wanted us not to mention Pollock in our discussion at all, and maybe this could be possible; but it certainly isn’t easy. He continues to haunt Krasner’s biography, and remained a presence in the Barbican retrospective, despite many reviews of the show positively declaring that finally Krasner is free of being defined as ‘Mrs. Pollock’. The exhibition’s curator, Eleanor Nairne, has said that she was ‘determined not to put together a straightforwardly feminist, revisionist interpretation of her career, because it wasn’t a case of him stopping her working’, and this wasn’t in doubt throughout the show – Krasner remained a tenacious and ambitious painter regardless of the challenges of her personal circumstances. However, before we have even seen the first painting in ‘Lee Krasner: Living Colour’ she has been married off to Pollock in the introductory text panel and her positioning as other to him, or painter despite him, was palpable.

Alison: I agree; we just haven’t seen enough of Krasner’s work in the UK to get to grips with it. How can her position in the painting canon be more deeply understood without us even being able to physically encounter her work? I was astounded by how long it has been since her last major exhibition here, and hopeful that this could have been the beginning of further surveys.

Clare: I suppose now I am personally more interested in reveling in the paintings, and in looking forward rather than back in terms of the gender politics around Krasner. Regardless of the patriarchal, heteronormative lens on them and the structures around them, which were particularly amped and extreme at that time, Krasner and Pollock’s lives were intertwined until death and that will be present in the work in both visceral and visible ways. There is a beauty in that which is outside of politics.

Alison: I wonder that if Pollock hadn’t met his untimely end, perhaps he would have eventually been eclipsed by Krasner anyway? In my mind her work is stronger. And maybe if that unfortunate event hadn’t happened, then the sense of a passed icon wouldn’t have permeated her biography? I suggest it’s because of the drama of it all that it becomes impossible to extract oneself from that narrative, regardless of gender or the obvious quality of the work.

EC: I also didn’t want us to dwell on Pollock, but sometimes what you resist, persists. Before visiting the show I heard a lecture by Krasner’s biographer, Gail Levin. I was struck by the extent of the falsities written about Krasner, many of which are still maintained by some art historians. Levin spoke about how Krasner was excluded from art historical texts about the first generation of Abstract Expressionists, despite being very much present in terms of her connection to many artists long before she knew Pollock – Gorky, De Kooning, Hoffman, and the critic Greenberg – that she introduced him to later on. Despite this connectedness of Krasner’s,of course, Pollock was written into accounts of the Ab-Exers and Krasner was not. Can we ever fully shake this bias off, the untruths and skewed realities of historical figures’ lives? And, like you say, as we have had very little access to her work in this country it felt like the scene had been set, long ago, for her to be viewed as Pollock’s spare rib.

Charley: Do you think we still need a ‘straightforwardly feminist, revisionist interpretation’ of Krasner’s work in the UK if ‘Living Colour’ hasn’t given us that? And does that actually have much to do with whether Pollock ‘stopped her working’ or not, surely this is a very reduced perspective on things, and probably not even the point?

EC: To my mind, a feminist, revisionist show might be exactly what is needed – Pollock not stopping her working is a minutia in the bigger picture of other injustices at play. A truly revisionist show would address this bigger picture more adequately. It’s astounding that her unfaltering ability to work is being framed as an issue. I think this tendency toward a myopic focus on Pollock is obtuse and is just one area of inequality to be found in Krasner’s case.

Charley: So maybe, if I was being provocative, then I might say that this is how things were then – that the narrative of Krasner as ‘wife’ superseded her identity as ‘artist’ because that was the value system that all women were subjected to, and that this was nothing to do with Pollock, and moreover a reflection of historical context. Perhaps putting a woke spin on this system today isn’t beneficial to Krasner’s legacy now, especially when most of us are aware of these inequalities, and hopefully know better?

Clare: Though of course I am so happy that we have been able to see this incredible show of Krasner’s work, my concern is that people do think everything is OK now because these gender imbalances are starting to be addressed, but there are so many untold stories about, unseen pictures of, and paintings by those who were and are marginalised or othered from the time of Pollock and Krasner; and this is of course still true today.

EC: Yes, let’s not pretend that things have improved fantastically now, in a time when people are still being described as ‘women artists’ but never as ‘men artists’. It is still standard practice to suggest that women are the deviation from the norm, some kind of ‘other’.

Clare: I am actually interested in what kind of a legacy this narrative might have – where those that are less visible or less privileged – such as people of colour, non-binary people, trans people, people who have neuro diversity, women, those with mental health challenges – are not consigned to what were herstories but could also be otherstories and have a voice and their work seen. This would be what I would see as a positive legacy to this story. I think of it as a seed from another time, though God knows those structures still feel firmly in place, particularly, it seems, in the field of painting. But I do want to look forward, and not back, if that makes sense.

Charley: I think that this is interesting in terms of a discussion about abstraction; I’m wary of subjectivity being brought into the conversation when I think it’s something that has marginalised women in art history and ghettoised us further into the ‘women artists’ category. But at the same time it is important to allow us all to accept an individual approach to practices and to feel that our voices are heard on whatever terms we feel comfortable with. There’s still a lot more to discuss around painting and biography, especially in non-binary terms. It’s not an easy issue to deal with comprehensively.

Clare: Exactly; I am interested in how biography impacts on the work- including my own work – but I feel that we should be allowed to draw these boundaries or say how we want to manage these things ourselves. However, it is complex.

Charley: And shows like ‘Living Colour’ have a lot of projection in them. Krasner was comfortable aligning biographical impulses with her painting, but I think the way she has become a historical figure takes biography as the overriding factor in how we approach her. This feels problematic. And what is abstraction if it doesn’t allow us to transcend definition by others and just make painting about painting, which men have always been allowed to do without the same convolutions as women?

Do we think it’s possible yet for exhibitions of ‘women artists’ to present the self as separate to or independent from the work? Why do we need stories about why women make things in a way that we don’t with male artists? Do we really need a reason to express something about ourselves in paint or can we just paint without our subjectivity as a validation for us working? This isn’t just a phenomenon that can be identified in ‘Living Colour’ – it is something that occurs often in historical surveys and defines a skewed perspective on women’s creativity. In ‘Living Colour’ in particular, there are times where biography is the primary lens through which we experience Krasner – over and above even her own interest in a personal narrative – notably for me in the architectural division of space in the gallery. Pollock lives and dies in the story presented in the upstairs galleries: the final room is a sombre hang of the violently deconstructed, fleshy forms Krasner painted before and immediately after she was widowed in 1956. This room is emotionally loaded, its walls painted black, and contextualised entirely around Pollock. ‘Prophecy’ (1956), which Krasner was working on when Pollock died, and the subsequent ‘Birth’ (1956), ‘Embrace’ (1956), and ‘Three in Two’ (1956) are complicated, visceral paintings that deserve deeper consideration than simply that of the circumstances in which they were made. These paintings feel like less of a departure from Krasner’s previous concerns than we are led to believe in the gallery text; their sensibility is closely connected to the monumental collage-paintings from the previous year, such as the dynamic ‘Blue Level’ (1955), and appear to conclude, for a while at least, an exploration of the Cubist techniques that began with her earlier Nude Studies from life in the late 1930s. If another artist should be mentioned in consideration of these works, it maybe should be De Kooning, whose ‘Woman’ feels like a more useful comparator in terms of resolving the concerns of rendering the body in disconnected space. By the time Krasner was painting ‘Prophecy’ in 1956, Pollock, at the height of his alcoholism, had almost stopped painting altogether…do we need to relate them so directly to him?

Alison: It seems that discussing gender and gender relations is prevalent when considering the work of a female artist, particularly where there is a lack of knowledge or understanding of the work. If the work itself enters into a dialogue about gender then this is obviously fair game, but if the work doesn’t go there, then why should any assessment of it? And it’s not just historical surveys where this occurs. It’s often an easy fallback for a lack of research. So will the question of gender always pollute writing about female artists? Whilst there is so much gender disparity in all walks of life, there will be people who won’t even realise they are following an elitist, sexist agenda by writing in such a way. And for those that do realise – well, we’ve all got better things to do than to listen to such voices.

EC: This issue is fraught with problems – partly because I think the show did need to address some myths or errors in the narrative about her life, and point out some of the discriminatory activity that was prevalent at the time; so Krasner’s story perhaps needed to be brought up. I’m not sure how we can wipe the slate clean and start again?

Charley: Maybe, but the theatrics of the show, the blacked out ‘tomb’ of a room containing the ripped- apart, fleshy paintings made at the time of Pollock’s messy death…did it all go a bit curation-as-soap-opera at that point? It made me smile, and that almost certainly wasn’t the intention.

Clare: If I am seduced or moved enough by the work then I am all about the autobiography with painting, regardless of gender. I am very interested in the idea with painting, in the best instances, that the affect or experience of the time is held within the materials and the stretcher and then flung back at the viewer in some bodily way. Therefore, in some senses the autobiographical is inescapable. Though I understand what you are saying, I think the thing that I feel most is that whether intertwined or defined by men or not – that within this period of art history there were so many female artists, queer artists and artists of colour, male and female – whose stories were never heard or are only just recently coming to light. So I suppose I would take soap opera over nothing, and it would be good to have some kind of spin-off series of those others who were not seen or heard. It was, after all, a great story, wasn’t it?

Alison: For Krasner, it could be argued that her relationship with Pollock, as an artist, was key in the development of her practice, but then couldn’t the same be said for Pollock? I feel that if you find you must discuss the relationship, then this ‘to and fro’ in their work needs to be highlighted in both practices? But that’s only if it’s essential to read the work through that joint lens. I would argue that a pure Krasner show- i.e., a Pollock-free zone- would be a fresh approach, a break from convention, and perhaps less histrionic?

Charley: I definitely don’t get a sense of a ‘to and fro’ in how their relationship as artists was presented. The ‘Prophecy’ room was like a stage set, with a spotlight on the ghost of Pollock. I tend to think we could focus more on Krasner’s work, which exists regardless of her biography. Krasner’s paintings are surely what art history should be interested in, not who she had been in bed with?

EC: Besides the ‘Prophecy’ room, regarding how the paintings that followed Pollock’s death were displayed in ‘Living Colour’, I am really in two minds. Krasner moved into the barn where Pollock had previously been painting and was able to work on a larger scale, so in a sense I don’t find those curatorial decisions to show this work downstairs that problematic. I can see that it was an important time in her work, in that there was a big shift when she suffered with chronic insomnia and adopted a muted palette to avoid using colour under artificial light. These circumstances allowed for changes in her painting. I can view this movement in the architecture of the show, and the dark walls in the ‘Prophecy’ room and so on, as being about Krasner and her determination to carry on with her work after Pollock, with two fingers up, as it were.

Charley: I can accept the logistics of showing the larger works in the gallery’s open space downstairs, but I’m still not convinced by some of the funereal window dressing or the romance of Pollock’s death being packaged up together with some great paintings by Krasner. I think I’d rather just see the paintings. Anyway, we’ve maybe said enough about Pollock, let’s talk about something else.

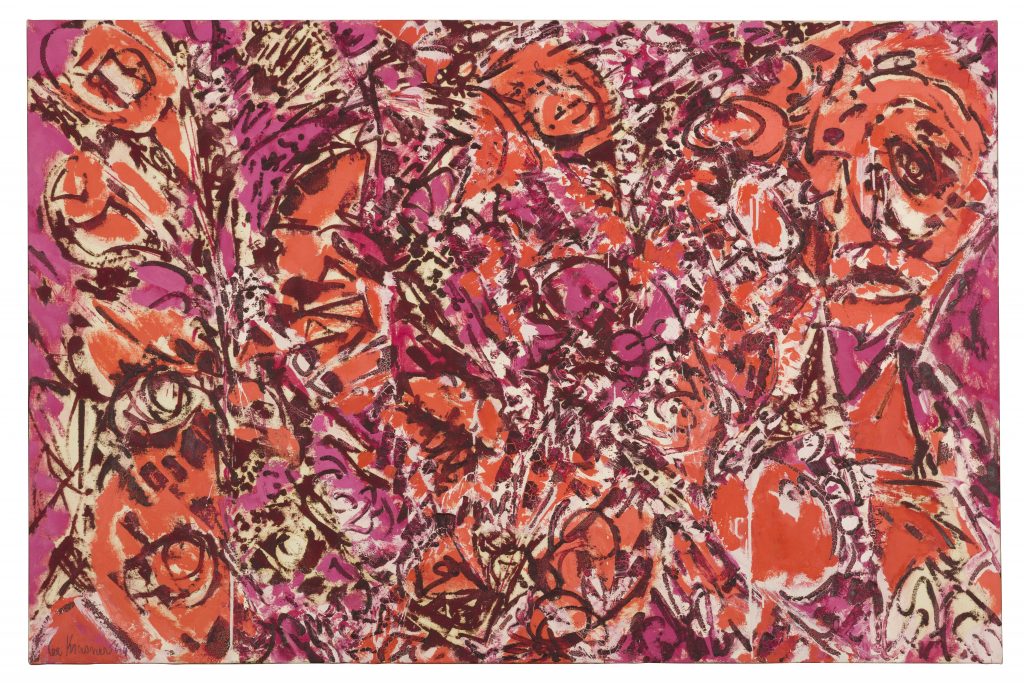

I’d like us to go back to something EC raised earlier about Krasner being disassociated from her immediate peers. I don’t think that the exhibition particularly positions Krasner as a first generation Abstract Expressionist and I wonder why not? Her biographer Gail Levin described her as being caught in the gap between two generations of painters – ignored in terms of the first generation of Abstract Expressionists as being just ‘Mrs. Pollock’ – and then being older and less ‘glamorous’ than the next generation, that included Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning and Joan Mitchell, in which women were more visible. I think what is exciting about Krasner is that she had a true breadth of enquiry in her work. There are intense cycles of activity and extended periods of investigation, but less so a signature style, which sets her apart from other painters of her generation. ‘Living Colour’ illustrates well Krasner’s back-and-forth between sweeping form and the hard-edge, pure abstraction and figurative concerns, monochromatic and vivid palettes. She described these transitions in her work as ‘swings of the pendulum’ without necessarily a linear development from one point to the next, but they were a series of recurrent themes that were returned to throughout her career. Does this make her distinctive amongst Abstract Expressionists or just less well defined as one, and is this problematic?

Alison: It’s interesting that you make the connection between Abstract Expressionists and glamour. And I think you’ve hit upon a key element in whether a female artist gets favoured by certain sources. Perhaps this would have played against her breadth of practice, which I don’t see as weaker as a result. As you suggest, the many concerns that ran throughout her work made her more distinctive amongst her Ab-Ex peers and potentially proved harder for less avid followers to ‘pick up’. Whereas, if we consider the work, say, of someone like Richter, whose practice has a wealth of threads, it’s not seen as problematic, but more as a productive level of enquiry where each approach supports the others. My question is, is this an example of gendered acceptance, i.e., of the pioneering male? And do we think this is the case today, where glamour (whatever shape or form that might take) influences the progress of a female artist?

EC: I hope it’s clear to most of us by now that Krasner was very much a first generation Ab-Ex artist. Perhaps she was ‘only’ caught in this generational gap by the persistent efforts of some old-fashioned critics and curators to exclude her. But she was very much there from the outset. The ‘glamour’ issue is interesting. That a woman’s work might be overlooked due to a perceived lack of glamour would be laughable were it not so painful a statement. I am not sure if ‘Living Colour’ did enough to position Krasner as belonging to the first generation of Ab-Ex. I did get the sense from the show of a human being who was isolated, but then, as I understand it, Krasner herself did not want to be part of a tribe or group and was very much independent too – was the show perhaps reflecting this?

Charley: I’m not sure, that makes it seem like disconnecting her from a peer group was somehow an additive gesture in the exhibition, rather than a reductive one. It doesn’t work like that though, does it; it surely means that she loses status? Do you think it is the way Krasner has been presented that sets her apart from the first-generation Ab-Exers, or the work itself, the ‘swings of the pendulum’ perhaps?

EC: Personally I am drawn to these ‘swings of the pendulum’ in the work of any artist. I think we swallow what is, in fact, a mantra of the ‘culture industry’, in that the idea of coherence is promoted as worthy. I don’t agree with this, although I’m sure that it makes it easier to secure sales. I think it shows intelligence and curiosity of mind to move around in your work, and for transitions to take place. For example, if Krasner had wanted to please Greenberg then she could have made the work that he wanted to show. She was consistent in her determination to keep exploring new concerns, despite the external pressures.

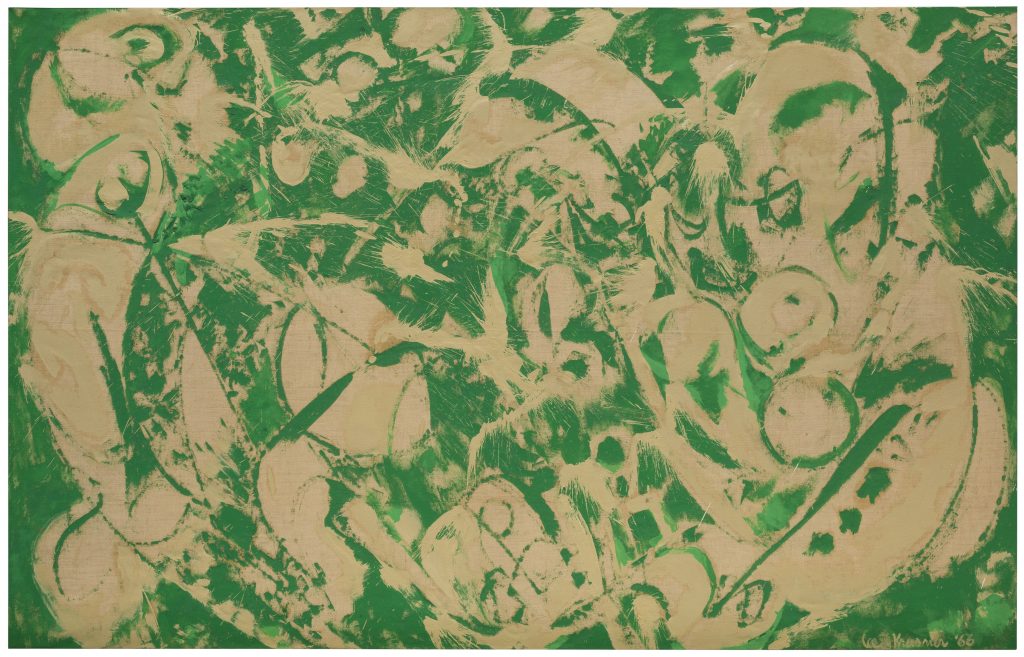

Charley: Despite all of her stylistic variations, Krasner’s works can typically be identified by their proficiency of compositional space, rhythm and colour. The second half of the exhibition in the downstairs gallery space confirmed this. Here we were offered the larger, more intuitive canvases, beginning with the umber-toned ‘Night Journeys’, made after Krasner moved into the larger studio. These are monumental in scale, many of them over two metres in either width or height, each painting in the series covered in confident arcs and sharp daubs of paint. The subdued ‘Night Journeys’ – the insomniac paintings that she began in the late 1950s in the barn – develop into vibrant colour when Krasner starts painting again in natural light. By the mid-1960s she was creating dramatic compositions with, in some cases, quite limited means. Paint is thinly and vigorously applied – by now her gestures were looser and almost calligraphic – and the works are held perfectly by her understanding of how different textures of painted marks sit together across a canvas, and of the importance of negative space. These paintings are vibrant and active but often have little surface texture – Krasner was a forceful painter but also a controlled one.

Alison: Throughout the entire body of Krasner’s work, what is evident is a relentless examination of what could be achieved with the materials at hand. Her tireless level of innovation is testament to the depth of her passion for this work; and for me this is what came across most successfully in ‘Living Colour’. I found myself just wanting more – I still do.

EC: I think we are all agreed that what clearly runs through all her work and is coherent is her sense of rhythm, ability to organise space and manipulate materials, even if these works are viewed as stylistically different. I do get spiky about the word ‘style’ as it implies something adopted and episodic – in one place and then suddenly in another, rather than found through a process of transition. Krasner’s work, whether chaotic or not, is all part of the same thing for me; an exploration that can be taken to either extreme and anywhere in between. She brings everything together into an organic, flowing form. Talking of which, I thought that Krasner’s link to nature was clumsily introduced in the exhibition, with those awfully placed photos of flowers taken by Ray Eames.

Charley: Yes, I thought they were terrible too – more unnecessary window dressing, and someone else taking up space that should have been Krasner’s. Keep that stuff in the catalogue please…

I’m still interested in the scope of Krasner’s work and how we might discuss it. For me she feels like a resilient artist for whom failure often inspired her most significant developments. Her first works of collage made from torn drawings (both her own and Pollock’s), newspaper and burlap, to which she added paint, came after an unsuccessful show that had prompted Krasner to rip up every drawing in her studio. Krasner’s collages from the 1950s, such as ‘Burning Candles’ (1955) and ‘Bald Eagle’ (1955) layer splinters of paper and paint together in a kind of visual disorder that is no less resolved compositionally for its apparent raw energy. Later on, when Krasner made ‘Eleven Ways to Use the Words to See’ (1977) she cut and reconfigured old life drawings into hard-edged elements on canvas. Her collage-paintings are interesting in a number of ways, they seem to be a means by which Krasner could activate new formal concerns and move on from what she considered a negative position in terms of her success as an artist. Perhaps there are issues of authenticity and originality that are worth considering around her reappropriation of drawings by Pollock the heroic innovator (yes, him again). And how do we relate the collages to the paintings, do they exist in different registers in terms of her practice, or shouldn’t we discriminate between the ‘Paintings’ (with a capital P) and what I’ll call, cheekily, the more ‘ephemeral’ collages?

Clare: It is almost funny now to think of the artist-as-hero myth, and in some ways maybe Krasner was ahead of her time in dismantling that and using his work for the collages – there is something very beautiful about that, I think. There is also a lightness that I suppose can belong to collage rather than the more ‘heavy’ role of painting – I like this lightness of hers, it adds a complexity and a kind of a wit. Collage and painting are both part of a practice and a story, and I don’t personally see them as having a hierarchy.

Alison: Krasner’s innovation, I think, is sometimes most evident through her reworking strategies. It most displays her belief that there was another solution to be found in her work. It also shows her tenacity, like a faith, that in never giving up, a way through could be found.For myself, this is an important lesson to be taken from this exhibition. It is one to share with my peers, and when the opportunity provides, in my teaching. I agree, it is a resilience that never pales in the face of her perceived failure. And her re-appropriating the work of Pollock is an extension for that ongoing dialogue. It also highlights the connectedness and makes manifest the networks that all practice demonstrates. However, I wouldn’t distinguish painting from collage in this case, rather see them as part and parcel of the same expanded conversation, a conversation that I endeavour, in my small way, to continue in what I do.

Charley: I’m trying to decide if it’s the use of Pollock’s cut-up works that I’m intrigued by, or the notion of reconfiguring existing works, full stop. There’s a couple of things I’m interested in with the collages: one is, of course, the issue of authorship; but also the collage practice of Krasner feels somehow distant to a first-generation Ab-Ex position – it’s more progressive actually. This maybe relates to what we were just thinking around her being acknowledged as a key figure in early Ab-Ex. By incorporating Pollock’s work, and her own previous works, into new collages, I think that Krasner created a sort of liminal space that transcended subjectivities, time frames and genre boundaries. I’m aware that I’m probably contradicting myself after critiquing her exclusion from the first-generation canon; but I wonder if her ability to escape definition could also be a good thing, in that it contributes to her being identified as an innovator? The collages are more interdisciplinary, the mashing up of individual elements from multiple authors across differing timeframes perhaps has a trace of parody, or is at least referential? They sometimes feel Postmodern. I think it’s helpful to think about these things, as it allows us to see Abstract Expressionism as a space that can be more contested, rather than a comprehensive entity. It makes things harder to define, but maybe that allows more artists to inhabit that open space, rather than being excluded from a fixed definition. And also, of course, the collages are really great. EC, as someone whose work is sometimes, to your frustration, described as ‘collage’, I’m interested to hear your thoughts?

EC: In Krasner’s collages the episodic elements – the cut-up ‘entities’ – are put together with an extraordinary sense of flow. In terms of the ‘painting’-vs-‘collage’ descriptors, my personal experience of making work is that of drawing that is using paint, as painting that is using collage, as collage that is using only paint. These are qualitative, felt experiences to do with relationships in the whole of the work, and not a scientific definition – otherwise everything that involves sticking things down would be collage and everything using paint would be painting. We know intuitively that this is not the case; we are not dealing with concrete definitions with no slippage. Krasner’s collages are very painterly and some of her paintings have so much ‘draftsmanship’, and she is great at it all!

Charley: And authenticity, and the work’s back and forth through her own history as an artist?

EC: I have some issues with the idea of authenticity as it is. Nothing is detached from art history and everything an artist has seen. I think of it, in part, as the reorganisation of visual energies that we have absorbed and learned. The biggest problem lies with Krasner using elements of Pollock’s work, but I think this is only contentious if we are still stuck on defining her by her status as ‘wife’. From what I understand, Pollock did agree to her using this material, and I see that as an artist using what is to hand, but primarily and intuitively as a decision that is somewhat autobiographical. I think that as an artist there’s an intuitive movement to pick up what is around you. In Krasner’s case, I think she was claiming her own story, her history, and instead of expelling it and regarding it as useless or in the past, she integrated it into the work as content.

Charley: We’ve started talking about autobiography again! Maybe this is a good place to end our conversation, it feels like we’ve covered some pertinent ground and, as is often the case, there are still more questions here than there are answers. Some of the issues we have discussed go deeper than the experience of the exhibition ‘Living Colour’ into how Krasner – and in turn other artists – have come to be seen as art historical figures. The relationship between (auto)biography and abstraction is complex, especially when applied retrospectively by, for example, curators looking for a way to make an abstract oeuvre more accessible. As EC said earlier, it can become engrained in our understanding of the work as a ‘truth’. And it’s not a phenomenon solely applied to the female experience – we are led to understand the likes of Van Gogh, Rothko, Basquiat and also of course Pollock as historical figures tinged by tragedy, but their biography tends to reinforce their significance, they are all the more special and interesting for it. It’s maybe not the same for Krasner and other women artists, and this has wider implications for how women are positioned in the history of abstraction; it dilutes their roles and casts them as co-stars in their own narratives. I’m not sure that we should ever trust biography as a lens through which to clearly see painting – no matter how great the stories are. The only thing that should be believed as truth are the paintings themselves, and this is the one thing that ‘Living Colour’ succeeded in showing us: Lee Krasner made badass paintings.

‘Lee Krasner, Living Colour’ was on show at Barbican Art Gallery, London, 30 May—1 Sep 2019

2 thoughts on “Charley Peters on ‘Lee Krasner: Living Colour’: Dead Husbands, Other Stories, Go Girlfriend!”

Comments are closed.

I really enjoyed reading this trilogue, thank you for a very engaging read.

I feel a great value of Krasner’s work is the way that she deals with signifiers. Picasso isn’t addressed in the discussion, and yet it is hard to imagine her or Pollock’s work without Him. Arguably Pollock’s trajectory was one of ‘triumphing over Picasso’. Picasso, of course, played a great deal with autobiography and ‘God-like’ creative genius. At the time of Pollock’s collapse into failure and death, Krasner self-consciously ‘goes back to’ paraphrases of ‘Demoiselles D’Avignon’.

The way she ‘goes back’ to European Modernism is fascinating to me. She of all the Americans was the most contemptuous of the notion of ‘American Painting’. It’s the sense of collage and bringing together different incompatible things into a sense of powerful rhythm that works across a range of different approaches and genres, addressed in the discussion, that now leaps out for me I think. At the exhibition I just felt that it seemed so ‘now’ and fantastically useful. Many of the paintings felt as if they could have been painted yesterday. Part of that, weirdly, was their sense of ‘belated’ nature.