Jillian Knipe in conversation with Daniel Sturgis

Jillian Knipe joins Charley Peters and Sam Cornish on Instantloveland’s ‘Writer-in-Residence’ programme.

Jillian Knipe is an Australian artist who has lived in London almost 20 years. Her studio practice encompasses paintings which use the familiar and arguably idealistic tropes of Modernism, alongside the complications of persistent memory and irregular patterning. She is currently developing the podcast ‘Art Fictions’, which is a series of discussions with artists through the prism of a book of their choosing. The aim is to explore stories of art making and the art of stories beyond the published novel.

Daniel Sturgis is a Professor in Painting at UAL Camberwell. He teaches on the BA, MA and PhD courses, as well as providing academic leadership around research. He has curated solo exhibitions for the work of David Troostwyk, Liz Arnold, Daniel Buren and Jeremy Moon, as well as several group exhibitions. He has also published a vast number of catalogue essays. As a painter, his approach to abstraction is an erudite one, bringing a contemporary sensibility to bear on his Modernist predecessors.

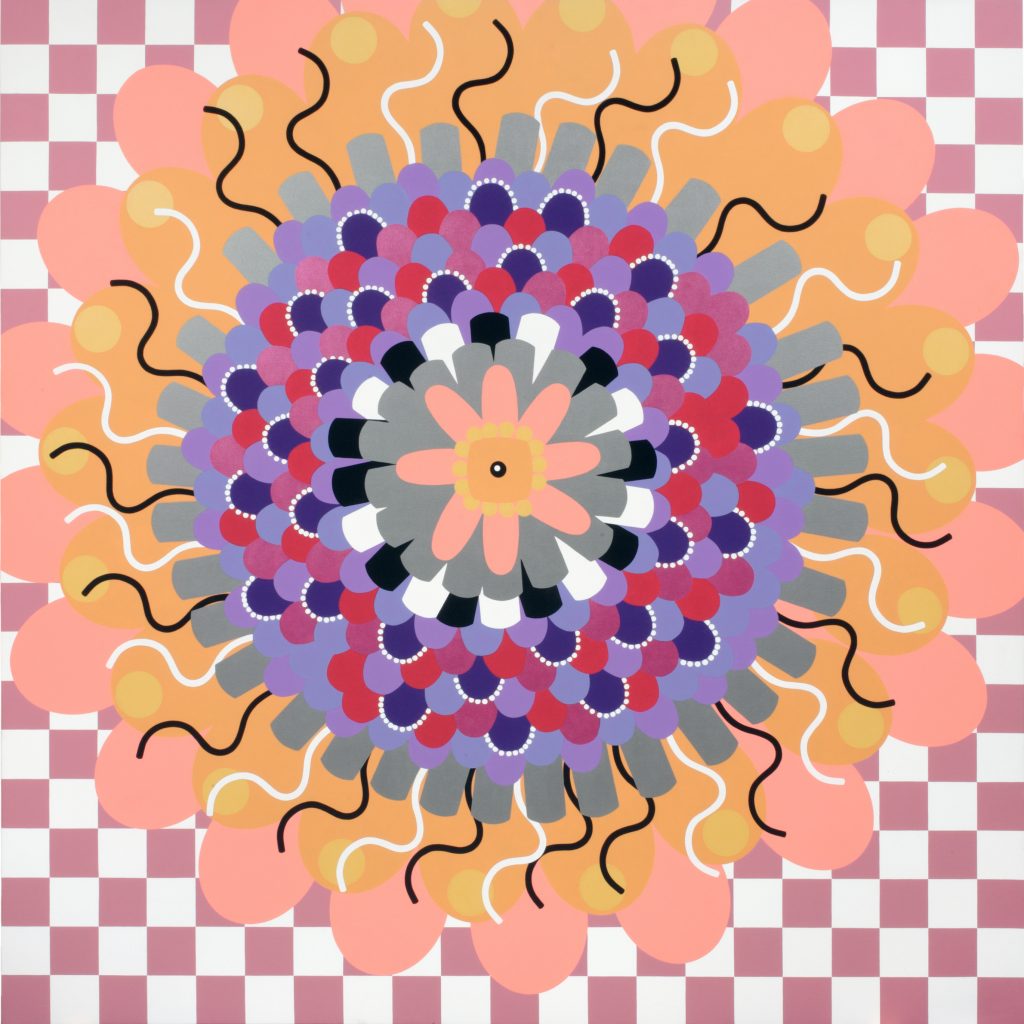

When I caught up with Daniel Sturgis to discuss his art practice, he was partway through developing paintings for his upcoming solo exhibition in Amsterdam and finalising details for his recently opened curatorial project ‘Bauhaus: Utopia in Crisis’, alongside teaching and supervisory roles at Camberwell College. This is a man who can multi-task! In much the same way as his early ‘Flower paintings’ work their way out from a central core to the canvas edge, his interdisciplinary practice reaches out from the central core of his own studio practice.

DS: I make paintings and have a studio practice and all of the exhibitions I’ve made, whether they’re one person or group projects, come out of the studio. They come out of what I’m engaged in within my own practice. The studio practice is the cornerstone of everything. When you’re making a painting, it takes quite a long time so there’s plenty of time to be thinking; thinking about other work; thinking about painting itself; thinking about connections. Then it’s interesting for me to think about how I can articulate some of those connections and thoughts. So that’s where the curatorial projects come from.

JK: You’ve located the group show you put together for Tate St Ives in 2011, ‘The Indiscipline of Painting’ in that context, particularly in your interview with Sam Cornish which appeared in ‘Abstract Critical’, where you emphasised that the exhibition was a selection of work by artists whose preoccupations related to your own studio practice at the time.

DS: I’m fascinated in the language of abstraction – though that’s quite a loaded term – and by its relationship to pictorial space, its relationship to design; and I’m also involved in a sort of argument about paintings being able to articulate themselves as paintings. So while I’m interested in how one painting relates to another, I’m not so interested in broad, expanded painting, like the assertion that film is a painting, installation is a painting, performance is a painting. Although I understand that argument, I’m more concerned in how the language of abstraction can be meaningful now. How a language which is basically an early twentieth century language (though its roots are much older) can still be seen to have relevance and not just be articulating known positions; rather, how it can be linked to the contemporary.

JK: I can see that pertaining to your own paintings, which we’ll get onto. First, though, I was thinking about historical context and the contemporary in relation to your Daniel Buren project. After Buren’s Modernist sail paintings were used as actual sails on a lake, they were housed in a gallery where they became, as you say, the work within itself. So when you re-enacted his work, putting the sails back onto boats in the lake, not only did these re-assert a characteristic of Modernism in a romantic setting, but both the romantic setting and the Modernist paintings became part of the one image, perhaps as a way to emphasise lineage.

DS: Absolutely right. The way that project came about was that I was invited to make some paintings on a residency at Wordsworth Trust at a point when I was thinking about painting and its relationship with romanticism and how that links with aspects of early Modernism. Also, I was thinking that abstract painting is often considered as contested and I’m not sure how meaningful that is. One of the things that motivates me is to negotiate its challenges; its confines. One of those challenges was the Buren project. It would be completely wrong to say there’s a relationship between what he’s doing and what I’m doing but I think that painting now has to understand what happened at that moment with Buren and the BMPT group 1The BMPT group was formed in the late 1960s and consisted of Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier and Niele Toroni. Based in Paris, and along with the Supports/Surfaces group and Simon Hantaï (whom Sturgis has written about). These artists led the way for Minimalism in France, advocating systems and repetition over subjective expressionism. he was part of, and with artists like Donald Judd who questioned the validity of painting. The reason I was invited to make work at the Chinati Foundation in Texas was that Judd thought of painting as an antique European mode and it was interesting for me to question how one can make paintings acknowledging that environment and context. I was particularly keen to study the paintings Judd made, which are all there in Marfa, prior to his move to ‘specific objects’. It’s about being willing and wanting to sail close to those winds.

JK: While you’re referring to Judd and to assertions throughout art history that painting is dead, that abstraction is dead, and so is the idea that abstraction is dead, you’re also continuing to paint. You acknowledge the idea of the end of painting while still making what could be thought of as traditional paintings on canvas. So how do those apparent contradictions sit together?

DS: I think that challenge is to do with a meaningful language or a language which has exhausted itself. This is what motivates me. I’m aware of the historical questioning of the medium which has happened through history at different moments, so the question becomes: Where does that leave a contemporary painter now? Do you just leave it, ignore it, consider it irrelevant? Or instead, do you recognise that those positions were important, and therefore how do you negotiate around them?

JK: You don’t seem to be afraid of taking on other artists who are looking at painting without using the canvas. Besides Daniel Buren, there’s the example of Pamela Fraser whose ’16 Colours Boulton’ (2014) was included in the group exhibition ‘Against Landscape’ which you curated. She photographed her placement of colourful rectangular prisms on rocks. It’s like an inverse of Carl Andre’s ‘144 Blocks and Stones’ (1973) where he placed locally sourced stones on concrete cuboids. In other words, Fraser’s work is a painterly image connected to some degree with another artist who’s largely associated with sculpture.

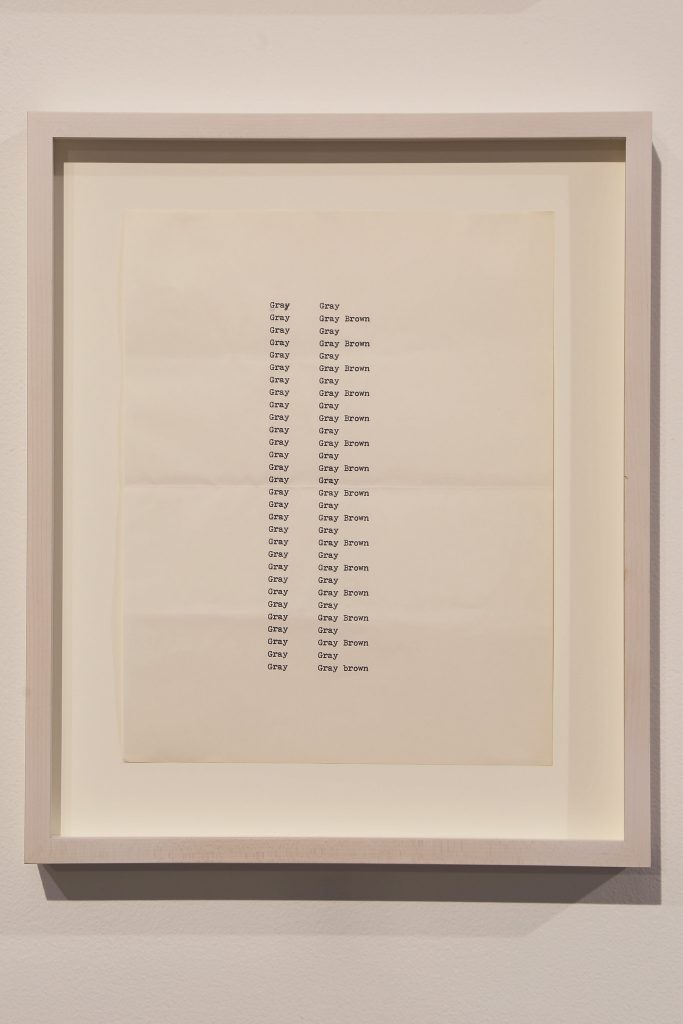

DS: ‘Against Landscape’ was thinking about a nervousness I had about the relationship between abstract painting and landscape which came out of my ‘Boulder’ painting series. At that time, I was asked, or rather, challenged by Grizedale Arts, to curate an exhibition about landscape painting. The one thing I didn’t want to do was to show anything that was very clearly a landscape painting; rather, I wanted to show works that had a strange relationship to landscape, or seemed to come from landscape, and that perhaps also had a rigour like the Sean Scully pieces which are lesser known text pieces based on colours, which are based on grids, which are based perhaps on Scully’s love of Ireland’s patchwork of fields. There was a nice connection there. It was to do with an awkward positioning, a slight discomfort in the territory.

JK: Connected to that is the idea that abstract work essentially comes from landscape.

DS: That’s a contested idea within abstraction. The question mark around that is one of the question marks in the exhibition, as is going on to ask: what is the residue of that now? For some artists, the idea of abstraction is to do with something more concrete, and not at all to do with nature. But I’m not sure if that’s ever possible.

JK: Whether it’s ever possible to know?

DS: Yes, take Barnett Newman for instance. He was deeply fascinated by the spiritual in American earthworks. He downplayed it, but there’s an element of that thought in his work.

JK: And what of the source of your own work? Do you have a sense of where your paintings come from?

DS: I think they come from looking at so many different things. Design, graphic design, the relationships within geometry, scale, human presence. The physicality of a painting, even if it’s only slight, is poignant in a machine age. I love the fact that Meyer Schapiro referred to paintings as ‘the last hand-made objects in our culture’ in 1957, and if that was say-able then what on earth does it mean now? I’m interested in the dichotomy of the way that composition can seem incredibly careful but quite casual. It would be wrong to say I’m specifically inspired by the landscape or I’m inspired by mathematics or music. But I’m definitely inspired by elements of all those things.

JK: I remember when novelist Tim Winton spoke of the Australian desert, which takes up most of the landscape and is therefore inescapably part of the national psyche. There’s no way you can not consider it, even when you think you’re not considering it.

DS: That sounds about right. That’s an interesting idea.

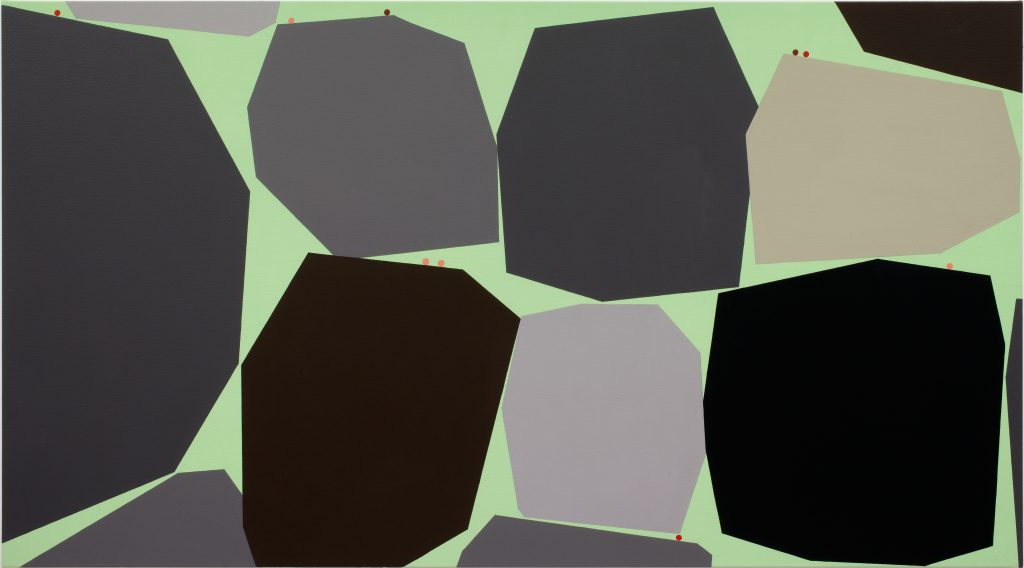

JK: Let’s go back to your paintings. One of the things I wanted to ask you about was your surface preparation. Connecting with the Bauhaus, you’ve spoken of wanting to be very clear that the work is made by hand even if it looks like an industrial output or recalls elements of design. It’s not just about the pencil marks which are visible up close, or about the way the paint sits very flat, or how you use a lot of thin layers to achieve even coverage. It’s also about the way you thoughtfully prepare the surface as a precursor to the application of paint. In fact, you once spoke of making a ‘Boulder’ painting and not being satisfied with the surface, so you made it over again, changing the technicalitiesof its making. Not that you can repeat the same painting, of course.

DS: I believe the touch of the hand is really important, and one of the nice things about painting is that everyone has had an experience of it, even if you’ve just painted a door. Everyone sort of knows what paint is. So there’s a link with the action of making a painting, far more than making a film or taking a photograph. Because the paintings are, in a sense, clean and graphic, which is part of the language. I want the surface and the way the paint is being handled to slightly reveal its making. And in doing so, to reveal that it is hand-made. The canvasses are slowly hand-primed, and that means you can see that they’re not pre-primed by a machine. I prefer the very slight imperfections in that kind of making; we’re talking tiny percentages. There’s also evidence of the shapes being drawn by pencil, painted by brushes and that the colour is not completely flat which reveals an aspect of the painting’s making which is to do with time. These images which look very quick have actually been made very slowly; and that slowness is an interesting thing to think about in a post-industrial age. There’s also an element of care in using very simple materials so that there’s no mystery in the making.

JK: Though there does seem to be a clear disorientation, with the very large and very small close together, which begs the question of where we ought to physically stand to look at the paintings. The size of the dot relative to the boulder might also recall Caspar David Friedrich’s ‘Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog’ (1818) with respect to the size of man relative to the landscape.

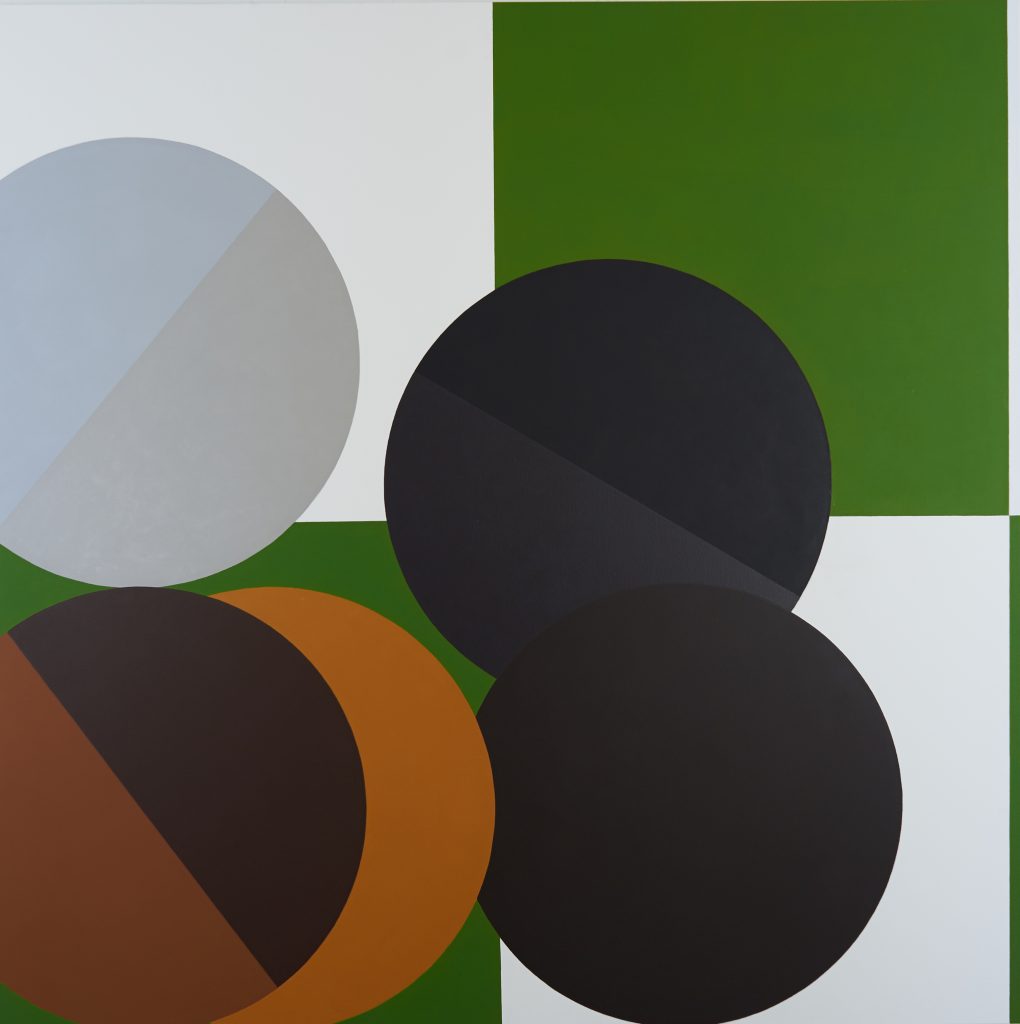

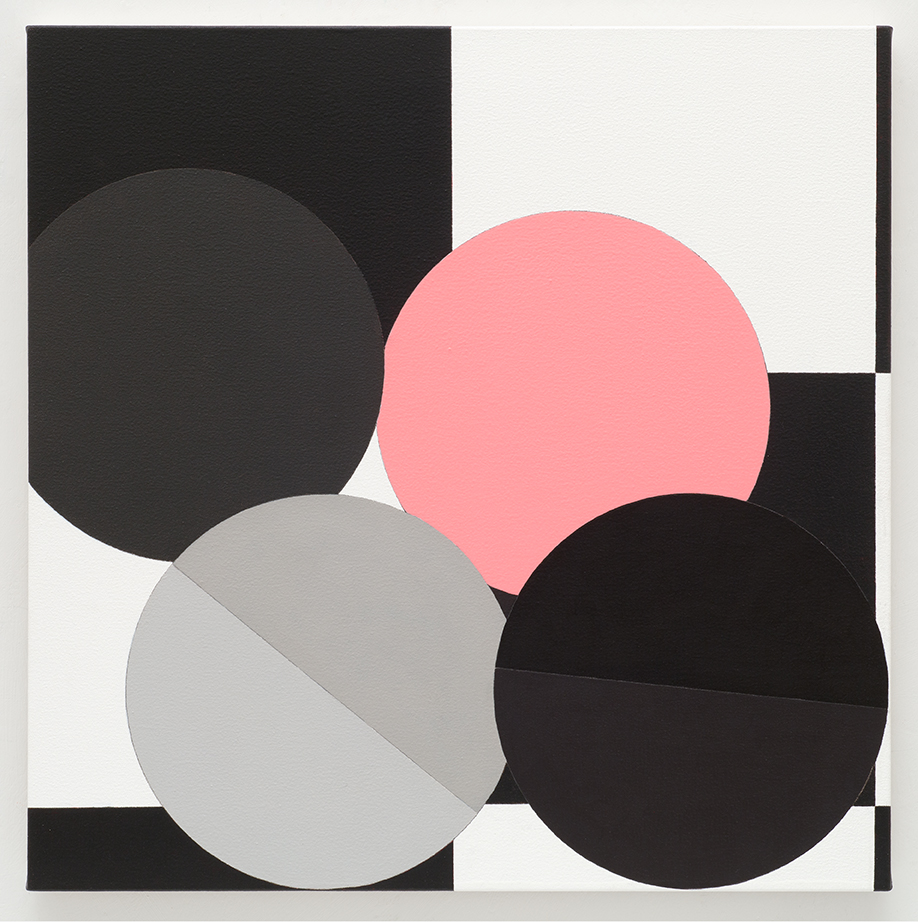

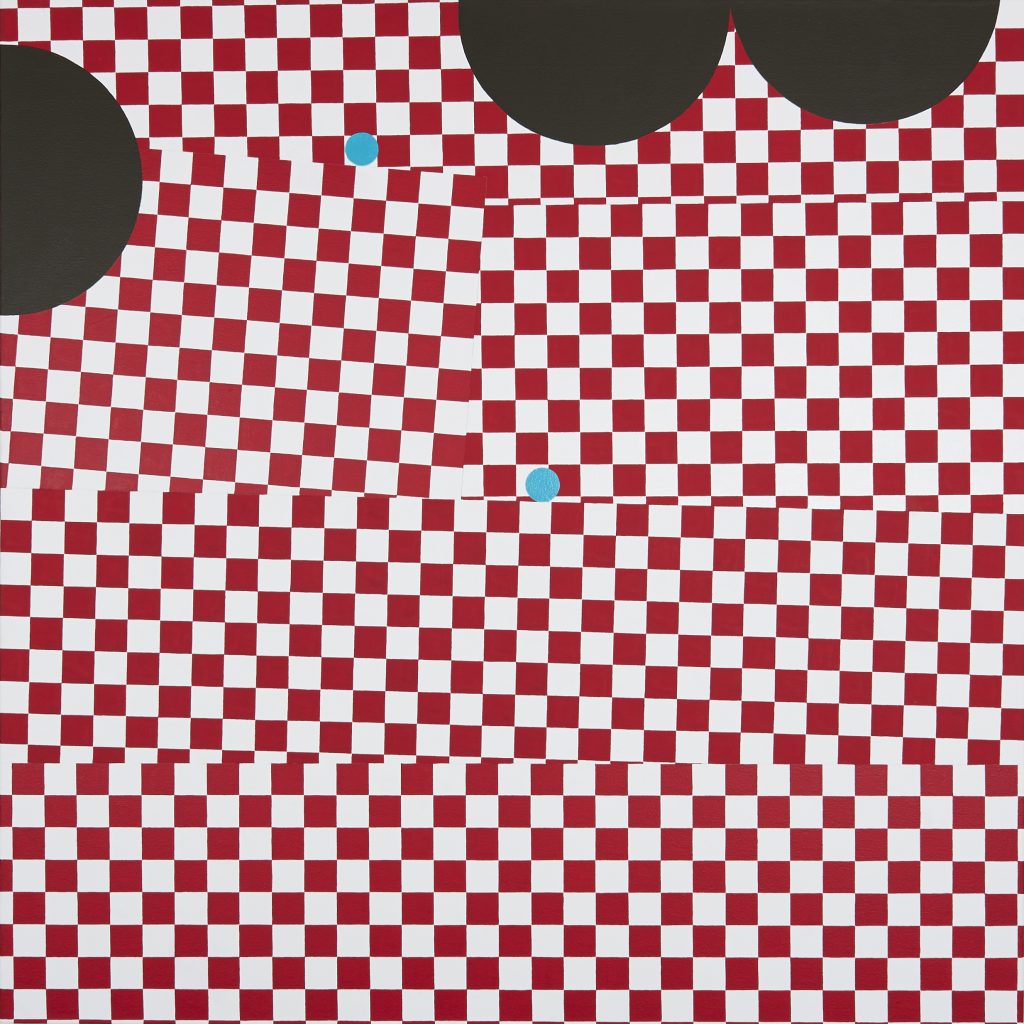

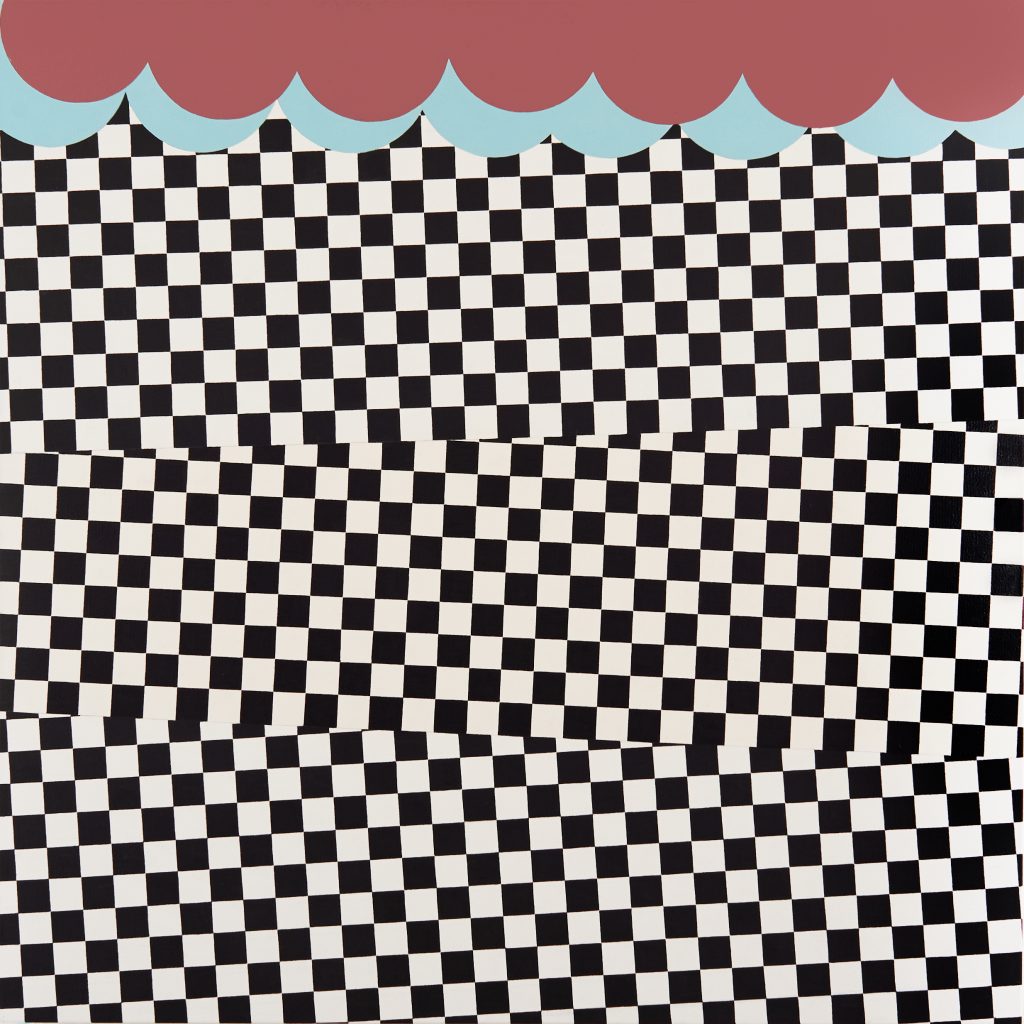

DS: I like the idea of dramatic changes of scale. The tiny dots in the ‘Boulder’ paintings were about that dramatic change of scale and, yes of course, the idea of figures in the landscape. Thinking back to the ‘Boulder’ paintings I showed in ‘Natural States’, an exhibition at Pier Arts Centre in2016 with Ingo Meller and Clare Woods, I’d been to Rackwick on Hoy where there were giant speherical boulders and I thought there was a nice play in them being so oversized. It was an extraordinary environment, so that was a direct landscape inspiration; but also there was a sort of provocative ‘formal stupidness’in making them so oversized in the paintings, first in the series of small paintings ‘Newer Older’ that I made in Orkney, and then in the larger canvases ‘Newer Older (Rackwick)’ and ‘Newer Older (That Summer)’ which I made later in London. I continued to think about the circle, when I made more circle paintings at the Albers Foundation in Connecticut, which explored bisecting and halving the circle whilst changing the scale of a grid or chequerboard patternbehind. The grid extending beyond the canvas, the circles being held somehow with their frames; but with an openness that enables them to navigate themselves within those spaces.

JK: With a line through the circles and what appears to be marginally different shading of each half circle, they are difficult to read. If the different shades were from a fold, then one half would be slightly angled. Yet they’re perfectly flat and evenly measured so they can’t be folds. And because they’re joined together, they can’t be two separate things.

DS: That’s right. The in-betweenness is important. In some paintings the two halves are actually the same colour, but the pencil line makes you assume there is a subtle difference. More recently, I have been thinking about the divisions inside the circle in relationship to the scheme of Leonardo’s ‘Vitruvian Man’; but again, shifting the centrality and rigidity of the vertical figure – ‘the measure of all things’.

JK: How planned is the work? Are you sketching your paintings first on paper, or loosely collaging cut-out shapes?

DS: I draw them out. I plan things that might happen in a loose way; these are things that might happen down the line. There’s another series of works I’m creating, in watercolours first, which is how I begin working out the colours. With the series of circle pieces I made at the Albers Foundation, I was thinking about colour relationships and wondering how you could have dark circles that weren’t quite black circles and how you could play with the relationship between different greys which you don’t read as actually different. There’s lots of little games in them.

JK: I’d like to understand your rules, if any, when you sketch something out. Are you making rules which apply to a whole practice, or to a painting, or to a series of paintings? Are you making rules, then breaking them as you go along? How do you hold onto or let go of rules in your work? Or do you not think of it in that way?

DS: You can see from the watercolour sketches, which happen first. They’re quickly done with a looseness to them but when I look at them I can see, in a sense, a more finished painting. And yes, of course things change when you’re working through the making process and an initial study is only ever an approximation. I like the slight imperfections which happen along the way. I go back to paintings and change elements and change colours so it’s not completely set at the initial moment; but, for instance, in this painting I knew very early on I wanted it to have three whites and be much more ordered. I knew I wanted the circles to be very casual and have this very different quality.

JK: Rather than working from the original sketch to the painting, what about within the original sketch or within the painting? Are there times when you think you might know how something ought to be, but you’d prefer to just do something else without understanding why? Do you let that happen?

DS: It all feels quite experimental. You need to do it to see it and see how it really affects the painting. Accidents happen; and some I allow, and some I don’t. Because I’m interested in things being what I call ‘casual’, or in being ‘inexact but precise’ which is a phrase Juan Gris used; I quite like that idea of things being very clear and regimented, but then there’s this other element which is much looser and because it’s looser you’ve got to go with it. Like decisions to tilt things or to stack things so that they don’t look quite right. The whole point of a painting is that it’s not supposed to look completely right. It’s not supposed to look completely balanced. It’s meant to ask questions about how a painting could be.

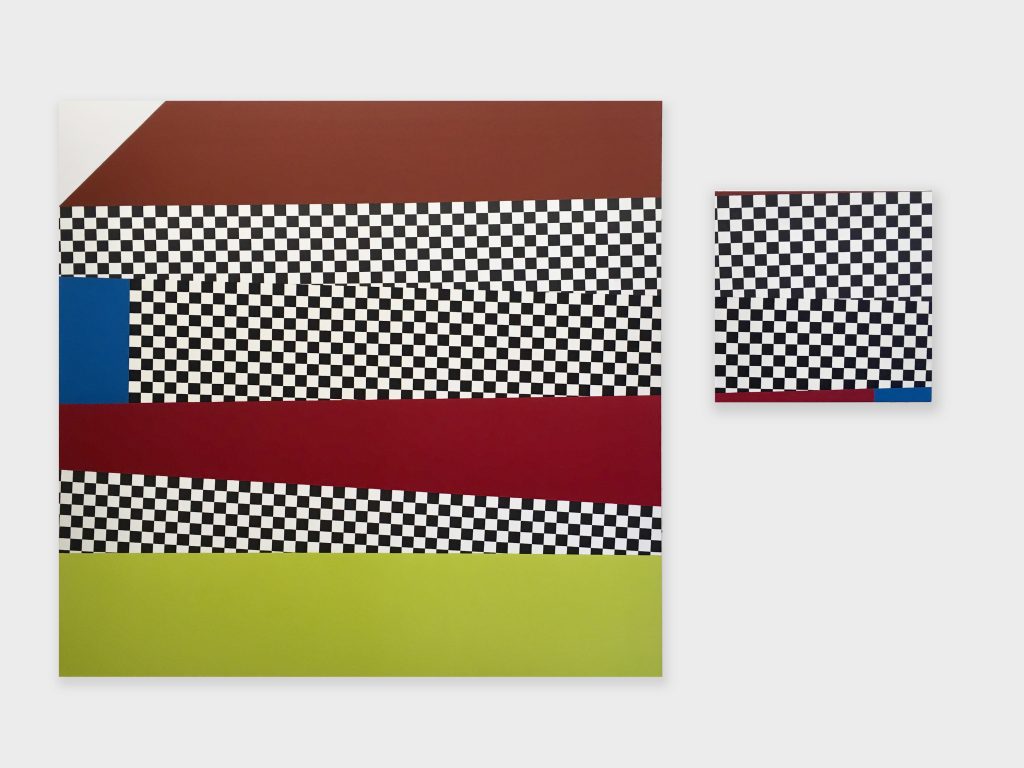

JK: Quite recently, I saw your ‘Two Paintings’ (2018), one 152 x 152 cm and the other 55 x 55 cm, in ‘Why Patterns’ at No. 20 Arts. Of course, there’s a lot more to your chequerboards than patterning, although I very much enjoyed that aspect of the paintings.

DS: That piece was also about the relationship between one painting to another. I’m drawn to equivalents. There’s an idea that paintings are unique and original, though not to anyone who’s a painter. In a sense, it’s a similar question to that in my current work and something I’ve done from very early on; Starting with what I call the ‘Flower paintings’, when I would make a very big one, then a very small one which was just an element of it.

JK: In your discussion with Jo Melvin you describe how ‘Fixed Directions’ and ‘The Way it is’ (paintings from 2018) relate to your work shown at Blain Southern by revisiting the slight disorientation caused by changes of scale and depth, and how the viewer is not quite sure how one plane relates to the other. You say ‘everything is very flat – screen-flat perhaps as opposed to modernist-flat’. Can you explain what you mean about the difference between ‘screen-flat’ and ‘modernist-flat’?

DS: The relationship between a type of conceptual or theoretical ‘flatness’ within Modernism and its possible manifestations of flatness within Modernist painting, has been discussed and thought about by many art historians and theorists. But what particularly interests me is the inheritance of that debate. One place to think that through perhaps, is with the relationship between the contained modernist frame and the expansive cinematic or digital screen. It is a relationship to do with the stability of edges and the flatness of surfaces. A digital flatness is evident of course in the multiple and unstable windows of a digital screen; overlapping but fully integrated. The digital real is often theorised as matrix like, vast and nodal, but, in a way, I like to see it in relationship to the painting – which is hand-made and material based – as an entwined knot of interconnectivities. A complex space that links disparate related positions like the historical and contemporary or the canonical and marginal and which then feeds back on itself.

JK: Coming back to your curatorial practice, how did ‘Bauhaus: Utopia in Crisis’ come about?

DS: For the last couple of years at Camberwell we have been looking at the Bauhaus, making a formal link with the historic Bauhaus Dessau Foundation and the Bauhaus University in Weimar. Partly this was to do with looking at specific exercises from Albers and Moholy-Nagy’s ‘Preliminary Design’courses that might be useful to re-engage with in the studios. Also, but more broadly, to discuss the role of an art school in society, its place within it and its civic responsibilities. The exhibition was another strand of this project. I was interested in thinking about how contemporary artists were engaging with the Bauhaus, especially around the role of women at the school and its more transgressive and political aspects.

JK: I’d like to finish our discussion with something about duality or multiplicity, without being too reductive! By that, I mean seeing from at least two different perspectives, as this seems to fit your paintings (landscape and abstract, figurative and abstract, stillness and movement or the potential to move), your curation (the self and the other, then and now) and is definitely an element in the work of the artists you’ve researched, including those selected for the Bauhaus exhibition. I was also thinking about doubletakes in your titles, such as ‘bolder’ and ‘Boulder paintings’ and ‘The Way It Is’ as both a description for how things are as well as the direction for how things are going.

DS: I agree. And I’ve spoken before about the attitude displayed by one generation to another; an attitude that allows practitioners to move beyond the impasses imposed by dominant histories – so the difficulties facing artists trying to make work ‘after’ the ends, prefigured in Vasari and Greenberg et al. The 16th Century architectural baroque -specifically Borromini – and the Emilian Bolognese school – the Carracci – rejected numerous stylistic tropes of the Renaissance while retaining others. So their works can be seen as both classical and anti-classical simultaneously. I believe this dual-faceted, multi-tongued or ‘perfidious’ mode of inheritance is necessary and interesting for rejuvenating abstract painting today.

‘Bauhaus: Utopia in Crisis’, curated by Daniel Sturgis, is open at Camberwell Space, Camberwell College of Arts, until 9 November 2019 and features work from the following artists: Juan Bolivar, David Diao, Liam Gillick, Interactive Media Foundation & Filmtank with Artificial Rome, Maria Laet, Andrea Medjesi-Jones, Ad Minoliti, Sadie Murdoch, Judith Raum, Helen Robertson, Eva Sajovic, SAVVY Contemporary, Schroeter und Berger, Alexis Teplin and Ian Whittlesea. The exhibition began as part of The University of the Arts ‘OurHaus’ festival, which ran 21-25 October 2019, coinciding with Bauhaus 100.

2 thoughts on “Jillian Knipe in conversation with Daniel Sturgis”

Comments are closed.

Frank Stella wrote in the 1970s of painting,‘that if something’s used up, something’s done, something’s over with, (then) what’s the point of getting involved with it?’ I’ve never been comfortable with this idea.

A negation of the past is one way to go forward but contains within it an arrogance and posturing of an ‘I know best’ expert, a heroic genius! Itself a remnant of earlier modernism, in which Stella had participated and by which his reputation benefitted.

David Reed’s position has always been preferable to me, where he has said that he did not ‘want to be the first or the last painter. I want to be part of a continuum. The image I have is of a conversation with artists of the past. We agree to disagree but carry on a dialogue.’

How pleasing therefore to see in the first photograph of this article one of Reed’s’ paintings from a series of Brushstrokes from 1975, shown 36 years later in the ‘Indiscipline of Painting’ show that Daniel curated for the Warwick Arts Centre and Tate St Ives in 2011.

The mixed New York show in which the ‘Brushstrokes’ first appeared, ‘Hard Times’, curated by Kathy Siegel, made a huge impression on Christopher Wool at that time, and fast-forward 40 years, these two curated a show at the Gagosian, New York, reviewing that period.

John Yau, a New York writer and art critic writing on the Hyperallergic website (Feb 25, 2017) recalled both shows in his article ‘Back When Painting Was Dead’. He said that he ‘maintained then (in 1975) and still maintains that an important body of work was being done by a group of New York artists, too young to have been Abstract Expressionists or Pop Artists or to join the coterie of minimalists and conceptual artists; who instead were painters when many considered painting to be in the doldrums.’

He continued that painting had been ‘narrowed down’ by Greenberg, Stella and Judd, who had overlooked one of its central features, its ‘capaciousness’. The rectangle was inclusive, not limiting, ‘anything could be made to fit in its shape.’ Unfinished business.

John Yau continued that ‘the moment when a narrative like Greenberg’s or Judd’s no longer limited painting is the moment when painting got interesting’ again.

There were artists then and artists now who continued to explore painting and its history, believing that it was not ‘used up’, but not to requote its memes and styles ironically or otherwise, but because they saw that modernism had stalled, and had more to offer by embracing its ‘diverse and antagonistic impulses’ and building on them.

I have enjoyed Jillian’s interview with Daniel, and see a similar embracing and development, and how interesting painting has become again.

Expansive feedback, thank you Ian Boutell, useful stuff. I knew of Kathy Siegel’s exhibition but not the John Yau article which I’ve tabbed open for later reading. Meanwhile, in progress is my discussion with Moyra Derby who also finds dismissive rules too constrictive as she refers to Judd’s assertion that ‘actual space is better than illusionistic space. The dogmatic, blanket statements of something being closed or over, just sweeps everything off the table. Things are discarded by applying that thinking. Things are attributed to not having any value. Think of when the work sits slightly off the wall and casts a shadow allowing you to look at edge and actual depth, one as marker of the other.’ Moyra goes on to talk about the potential joining of the edges of the rectangle. The possibilities go on.