John Bunker: ‘New Creation Myths for a Menippean Abstraction, Part One: Cubism and the Kingdom of Thingdom’

Hilma af Klint’s abstract works, currently on display at the Guggenheim, New York reflect a contemporary need to ‘spiritualise’ the creation myths of abstract art. According to the Guggenheim, ‘People are going nuts for her work and the show is the buzz in the art world.’ Ben Davis, in Artnet.news, writes ‘I can’t help but agree with all the praise being heaped on the Guggenheim’s big Hilma af Klint show. It’s great, great, beyond great…the show feels like both a transmission from an unmapped other world and a perfectly logical correction to the history of Modern art—an alternate mode of abstraction from the dawn of the 20th century that looks as fresh as if it were painted yesterday…[the paintings] return a sense of mystery and order to a world that seems dispiriting and beyond control’.1Davis, B in https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/hilma-af-klints-occult-spirituality-makes-perfect-artist-technologically-disrupted-time-1376587 The idea, then, that abstract art is full of spiritual messages ‘of mystery and order’ still fascinates; indeed, its history is littered with many sacred offerings, whether it be af Klint’s ‘Altarpieces’, Mondrian’s theosophically-inspired works, or Malevich’s Black Square, which, in its cracked and blistered state, is indeed looking more and more like a holy relic these days.

In terms of the creation myths we currently take for granted, Cubism and Postimpressionism are generally seen as the movements in art that cleared the way or created the kind of environment in which abstract tendencies in art could properly take root. The mysticism and religious fervour indulged in by the likes of the ‘Nabis’, Gauguin and Van Gogh are well documented. Postimpressionist art, in due course, turned more toward the exploration of the power of colour in paint; nevertheless, notions of mysticism, spirituality and intimations of the sublime persisted. In Cubism, though, we see the world reduced to a set of signs. Here, pictorial invention takes its cue from the real world; yet that real world is transformed by being forced against the inherent geometries of the stretched canvas and the reality of the picture plane.

Of course, in terms of the history of Modern art, Cubism is assumed to play a central role in redefining visual art’s autonomy; in pursuing an ideal of painting back to the notion of an essential ‘plastic purity’. We recognise Cubism as a standard bearer of the pre-WW1 avant garde; but it also became synonymous with what was known as ‘the call to order’ that took hold in the arts across Europe after the devastation of The Great War. This new cultural conservatism can be understood in terms of the need to essentialise painting’s supposedly timeless values, such as harmony and order, as a reaction to the deepening economic and political uncertainties plaguing Europe. In their quest to purify the arts and reject ‘extra-painterly concerns’, critics of the day looked to paintings such as Picasso’s ‘Two Women Running on the Beach (The Race)’ of 1922, in which neoclassical figures frolic on a timeless beach under unchanging azure skies; and to cubist works such as his delicate ‘Still Life’ of 1922 that, on the face of it, seem to suggest quieter interior worlds and simplified, contemplative abstracted spaces.

Paul Durmee boldly asserted:

‘The literary painting or the pictorial literary are symptoms of decadence. In classical times, the independence and autonomy of each art were carefully safeguarded. No overlap or penetration; purity!’2Dermee, P ‘Un pochain age classique’ Nord-Sud 2, no. 11 (Jan 1918)

Teriade (the nom de plume of Efstratios Eleftheriades) made the claim:

‘Cubism brought a new purity to painting and succeeded in fixing for a few years the movement of classicism.’3Teriade ( Elestheriades, E) ‘La Avenement Classique du Cubisme’, Cahiers de’art (1929), p452

But the audacious plurality of Picasso’s approach as he openly worked on Cubist and Classical works simultaneously, the chopping and changing of styles, and the forcing together of what might seem like discrete or contradictory ways of working, shows, at best, a deep ambivalence regarding such overarching theories of ‘classicism’. By this time, Picasso’s Cubism is viewing not merely the subject matter of the painting, but the act of painting itself, from multiple perspectives; allowing him to explore seemingly contrary positions and philosophical perspectives on painting. Cubism had gone from being a way of seeing the world, to a way of being in the world. This release of deconstructive energy pushed Picasso into the darker territories explored in the ‘Three Dancers’ of 1925 and ‘The Kiss’ of the same year. Even Gris, arguably the most systematic, and hence most limited of the three originators of Cubism, was, by the late teens and early 1920s, exploring, in a more experimental mode, the possibilities of the anthropomorphic transformations latent in objects. In ‘The Glass’ of 1919, we can see the teasing-out of silhouettes and shadows; using visual incongruities that offer a glimpse of a head with a single Cyclopean eye or inverted open mouth before reverting to an image of a glass on a table. These sliding signs and ambiguous shapes, shifting from one visible state to another, nag at the notions of ‘purity’ and geometrical harmony that have clung to him.

Cubism’s subversive visual wit derives directly from its radical reductions and recalibrations of the visual realm: thus, it can be seen as a ‘machine’ for the constant reorientation of the potential of the visual field; it can be turned in any direction, whether that be towards austerely abstracted still life works, or towards a heightened, almost hallucinogenic representation, as in Picasso’s ‘Three Dancers’ or Gris’s ‘Pierrot’ of 1921. These oscillations and distortions frame the picture plane as a playground for visual puns, non sequiturs, puzzles and heightened perceptual ambiguities.4Of course, Marcel Duchamp was also, for a time, making paintings that mixed in a kind of proto-Cubism with forms derived from Futurism, as the tonal modelling and facet-planes of ‘King and Queen surrounded by Swift Nudes’ and ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’ testify; that is, until the development of the ‘Readymades’ led him out of painting altogether, and therefore beyond the scope of this essay.

The extent to which Cubism departed from its assumed function of providing some kind of autonomous, harmonious and continuous visual experience, freed from the temporal vagaries of visual perception, is demonstrated in Picasso’s ‘Seated Nude’ of 1909-10. It is, on the contrary, a disturbing and alienating image. This example of analytical cubism presents to us the collision of many tiny illusions based on irregular angular dissonances and disruptions of the picture plane. These tonal shards of cold space, drained of colour, attempt both to add up to the torso and head of a female figure and at the same time to assert their power to hollow out and fracture the image. Just when the curvature of an eye socket in the centre of the painting’s top third might anchor our gaze, the figure disintegrates into a painterly prism of claim and counter-claim as to what is actually there before us. Larger angular shards that might have depicted drapery and an interior architecture dramatically fall away diagonally to the right of the painting, almost peeling away the side of the figure’s face in the process. These strong rightward diagonal movements are then countered by the disturbing rigidity of the bony box-like forearm forcing itself both out toward us and away to left of centre. Suddenly it feels as if we are in a new kind of visual psycho-drama. It is no longer a question of representation per se; the question is now, what is painting for? Cubism is supposed to assert painting’s autonomy by focusing down on its particular characteristics and internal logic. So far, so Modernist. But in truth, it’s a conflicted autonomy, antagonised by visual incongruities as much as it is purported to muster harmony, unity and wholeness….

In de Chirico’s ‘The Uncertainty of the Poet’ (1913) we see a deliberate attempt to produce an overtly mysterious image, courting classical references and artfully juxtaposing incongruous objects in shadowy architectures. Picasso’s ‘Seated Nude’ (1909-10), on the other hand, is a direct result of a profound scepticism about painting’s ability, at this particular point in history, to articulate the very nature of visual perception itself. Maybe this is what Picasso meant by Cezanne’s ‘anxiety’? Cubism seems to be a concerted attempt to exploit that anxiety and take it to new extremes.

We find a similar sense of cascading visual disintergration in Braque’s ‘Violin and Palette’ of 1909. The trompe-l’œil nail on which the artist’s palette hangs seems to both visually and symbolically hold the centre amid the disintegration of the objects and the space they inhabit. It is a clear deconstruction of the still-life genre that deliberately plays illusionistic, representational space against its almost dramatic dissolution into a series of signs composed of fractured diagonals and faceted planes. With these wilful distortions comes a certain kind of psychological charge. This charge seems generated by a kind of friction or exquisite tension between ever more severe reductions on the one hand, and constantly evolving complex geometries on the other.

In ‘Satirizing Modernism: Aesthetic Autonomy, Romanticism, and the Avant-Garde’ Emmett Stinson suggests how an author’s autonomy or sense of self is at once summoned and critiqued in literary modernism…

‘My suggestion is that, rather than serving as a coherent philosophical position or a model for utopia, modernist autonomy be reviewed as a rhetorical strategy or gambit that posits the work of art’ s separation from political or social forces from which it can never be truly free.’5 Stinson, E ‘Satirizing Modernism: Aesthetic Autonomy, Romanticism, and the Avant-Garde’ (Bloomsbury Academic, 2017) p9

What if we view Cubism in this light, as a ‘rhetorical strategy or gambit’? It would then offer us a very different concept of artistic autonomy. We begin to see Cubism’s potential as a form of satire: one that bears down on the process of painting, and on the very nature of perception itself.

Satire, in its subtle, gentle Horatian mode, looks to educate through clever questioning of dominant opinions, social mores and beliefs; its Juvenalian mode is far more overtly critical and combative in its interrogation of power. If we allow that a Graeco-Roman literary form might prove useful as a key for unlocking the codes of visual art, then it becomes possible to say of an artist such as Pieter Breughel the Elder that his work exemplifies the Horatian mode, tempering the critiques of human folly in his genre paintings with a witty humanism; whilst the savagery of Otto Dix and George Grosz can be understood as thoroughly Juvenalian, since it channels the anarchic spirit of Dada and Surrealism, via a kind of vernacular Cubism, into withering attacks on the warmongers of the Third Reich. In our time, painting has long since been supplanted as the primary means of social commentary by other forms of cultural production: for example, the popular, long-running satirical show ‘Have I got News for You’, by turns affectionate and abusive, embraces both Horatian and Juvenalian modes.

However, it is a third mode of the satirical- the Menippean- that more closely concerns us here. To describe the ways in which it differs from the other two modes in contemporary terms, we might say that the Horatian and the Juvenalian stand in the same relation to it as ‘Have I got News for You’ does to ‘The Day Today’: the former focuses on real events, individuals and groups who are making the news, whilst the latter obsessively scrutinises the means by which the news is delivered to us; it subverts the conventions utilised in televisual news coverage, and the distortions in language that spring up via the medium; it forces the sometimes dark aspects of the psychological into direct competition with the factual. And it is this concern with the forms the message inhabits that marks it out as Menippean satire. The Menippean operates by invading genres; it hijacks other literary forms, spinning a multiplicity of narratives and jumping between viewpoints and voices. It lends itself to the exploration of grotesque exaggerations of psychological states, while maintaining a cool intellectual rigour that functions as a distancing strategy. It mixes verse and prose, highlighting the widespread propensity for delusional adherence to philosophical or intellectual dogma.

In literature, the Menippean mode can be easily found both in Modernism and Postmodernism; but there are also interesting and revealing continuities to be explored between these and certain aspects of Modernist visual art. In particular, direct correspondences can be found between Menippean satire and the Analytical and Synthetic Cubism of Picasso and Braque.

In Synthetic Cubism the play of signs- the found against the painterly- is the product of heightened self-consciousness and self-reflexivity. Analytical Cubism’s tonal modelling of planes yields to unmodulated colour; there is a new appreciation of the properties of found materials.The real edges of collaged wood, metal, cardboard, wire and other found objects pit brute materiality against the virtuoso illusionism of finally modulated planes. Picasso’s series of constructions based on the guitar motif exemplify Cubism’s sheer visual invention: their arrival had drastic implications for both sculpture and painting. Sculpture found itself opened up to the spatial possibilities of planar construction. Picasso’s wall-based works insist that painting has to deal with its new-found relationship with objecthood; its reality as a thing eclipsing its role as conjurer of painterly illusions. So much for all those classical ideals and po-faced purity; the smashing together of materials and codes of representation is what counts. Cubism is not some miraculous harbinger of an entirely new and pure visual language; it is, rather, in true Menippean mode, a playing off, one against another, of competing visual codes.

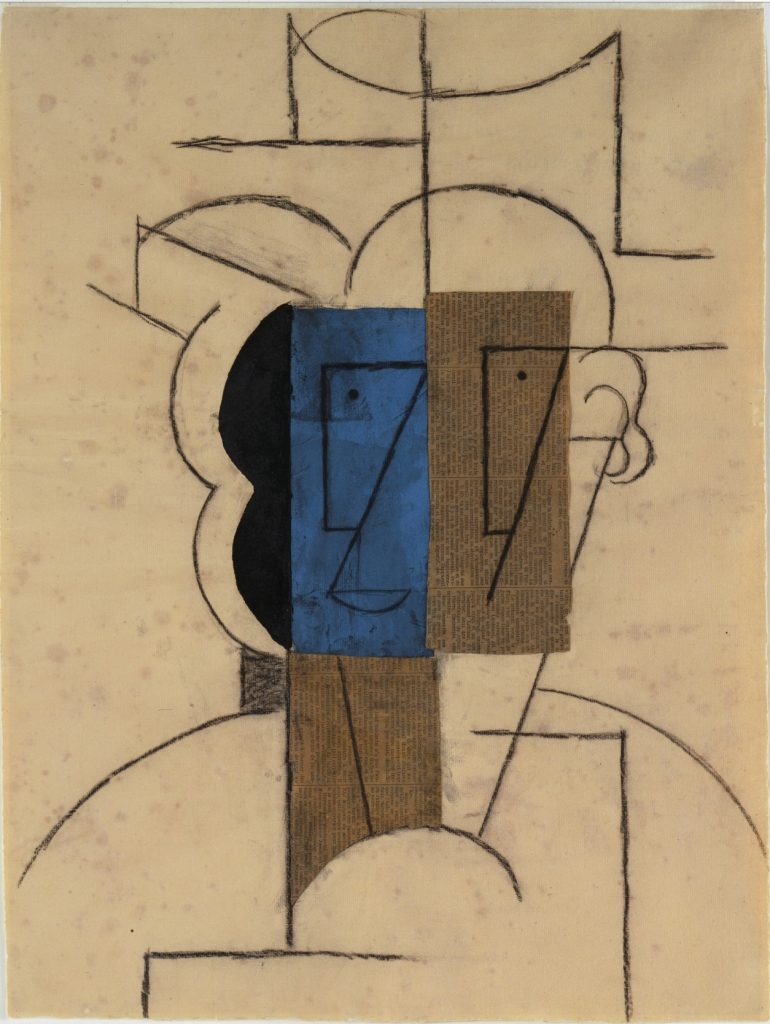

Pablo Picasso, ‘Head of a Man with a Hat’ (1912), cut-and-pasted newspaper and coloured paper, ink, and charcoal on paper, 62.2 x 47.3cm

Picasso’s ‘Head of a Man With a Hat’ of 1912 reduces the human form to a set of circles and squares: it is not only an extreme visual simplification, but also a provocation to the era’s pervasive, self-serving, woolly humanism. It hints at how the machinations of capital and the formation of selfhood might be entwined. In its deliberate attempt to empty out this bourgeois of any sense of personality and reduce him to the signs of wealth and class- distilled to a newspaper cutting and the tilted arc of a top hat- it appears to be satirising the autonomous self, that foundation on which so much of the narratives of autonomous art rely.

Stinson suggests that these notions of artistic autonomy are always haunted by shadows:

‘Claims of autonomy are never completely autonomous because they can only derive their meaning from the disavowal of an external tradition, institution, or discourse. Autonomy is thus always defined by this negative relationship to a disavowed externality…In this sense, claims of autonomy are always shadowed by the externalities they seek to escape.’ 6Ibid, p8

He goes on to consider how authors have been re-imagining the role of satire in Modernist and postmodernist writing; turning it away from its ethical or moral origins toward scrutiny of the fault lines in notions of artistic autonomy. How do these fissures impinge on our consciousness, mediating sensation in the tumult of modernity and, now, postmodernity? Fredric Jameson, for his part, offers a pessimistic interpretation of the dilemma of the artist operating amidst the de-centring of subjectivity and autonomy in the postmodern era:

‘If the experience and ideology of the unique self…is over and done with, then it is no longer clear what the artists and writers of the present period are supposed to be doing.’7 Jameson, F ‘Postmodernism and the Consumer Society’, in ‘The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983-1998’, London, Verso, 1998, p6-7

But as we’ve seen, aspects of Cubism question this ‘ideology of the unique self.’ Its satirical impulse breaks open the received visual rhetoric of the age; but it also offers up a Menippean satire of the ‘unique self’.

Jameson’s notion of a postmodern sublime posits the idea of a terrifying, hyper-networked world, a hysterical, information-driven, image-riven and rampant capitalism; as incomprehensible and unforgiving in its intensity and complexity as what was once perceived as the sublime of nature. Could a reappraisal of notions of radical autonomy be a way to resist absorption into such all-seeing, all-controlling global capital?

Cubism openly both courts our projections and refuses them. By asserting its objectness, its flatness and its conflicted autonomy, it both proffers its mimetic qualities and confounds them. Thus, the work of art can become a Menippean theatre of visual conundrums, setting the creative impulse free to roam in a new kingdom of thingdom; a new realm of positive and negative spaces where silhouettes and shadows take on the fullness of sentient presence, while a living head and body are cast as almost lifeless automata. Cubism offers the prospect of a new way of seeing based upon an artistic autonomy which can both break with tradition and produce new forms. Yet, at the same time, it produces images of extreme fragmentation, decentredness, images within images, materials as materials replacing pure painting, the integration of stencilled words, portraits that simply reveal masks behind masks, identities atomised into plane behind plane behind plane. Cubism does not offer some coherent new world view based on the fantasies of complete autonomy proffered by the between-the-wars classicists; nor does it propose a visual equivalent of the Theory of Relativity; nor, indeed, is it simply a staging post on Alfred Barr’s or Clement Greenberg’s long straight road to ‘pure’ abstraction.

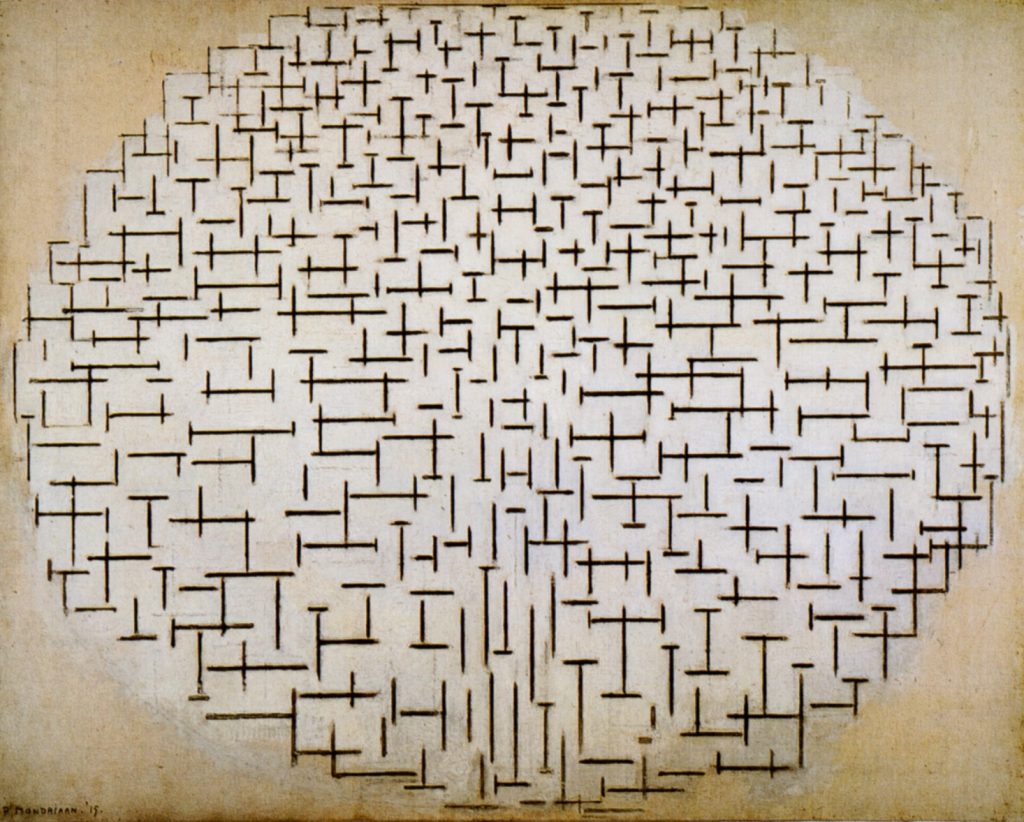

Mondrian’s ‘Pier and Ocean’ paintings are both abstractions of their ostensible subject into a simple interplay of vertical and horizontal lines, and a stage in his theosophical quest to discover the underpinning structure of our universe; and, as such, are understood as a seminal moment in Modernism’s ‘Grand Narrative’. However, rather than considering these works of art in this pious spirit, as manifesting a direct route to sublimity, what if we opt to view them through the lens of Cubism’s satirical mischievousness? Seen in this way, Mondrian’s mysticism merely swaps figurative storytelling for another imagistic narrative formed from shapes and symbols that are reliant on, as a visual base, a rhetorical classicism and a clichéd hotchpotch of visual equilibriums, compositional weights, measures and predictable checks and balances; a hotchpotch which fed that between-the-wars hunger for everything classical in painting, at least for the short time in which its defining characteristics strangely tallied with aspects of the development of abstract art. It seems, though, that for all the theoretical posturing and theosophic evangelising, Mondrian’s greatest debt is not to the mystical revelations to be had in theosophic texts, but to the witty capriciousness and shape-shifting, rule-defying audacity of Cubism.

As we head toward the end of the first quarter of the 21st century, we are witnessing the decline of the natural sublime and the ascendancy of its postmodern counterpart, the man-made realm of images. No wonder the spiritual narratives that blend clichés of classicism with the search for the abstract sublime, to which Ben Davis alludes with obfuscating terms such as ‘mystery and order’, might be beguiling to the jaded contemporary Western world; but I would argue that it is the quotidian, Menippean toughness at work in Cubism, a Cubism freed from its lingering, undeserved reputation as a pictorial language of classical refinement and repose, that is the more fecund historical precedent for a new abstraction. It is the darker aspects of the Cubist worldview that feel far more at one with the contrary nature of an autonomous art and its fraught relationship with Modernity and Postmodernity.

Pablo Picasso, ‘Bottle of Anis del Mono, Wine glass and Playing Card’ (1915), oil on canvas, 46 x 54.6cm

Pablo Picasso, ‘Study for a Guitar on a Table’ (1924), pen and Indian ink on Arches paper, 31.5 x 23.5cm

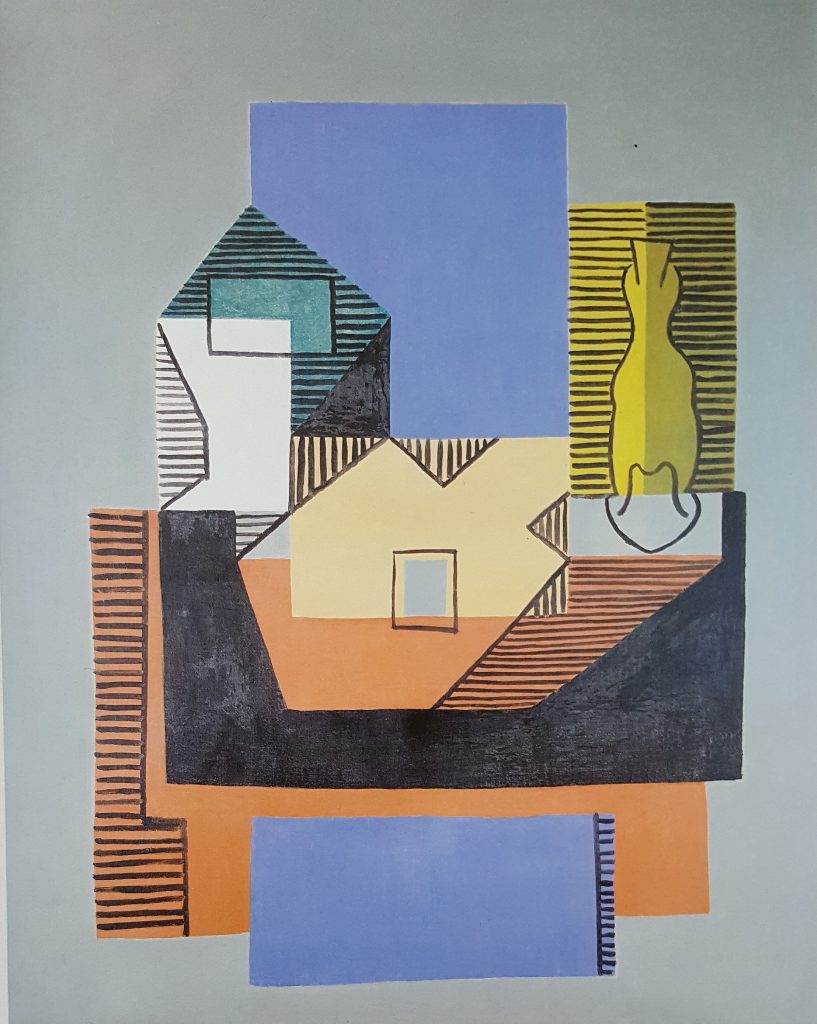

Pablo Picasso, ‘Still Life with Door, Guitar and Bottles’ (1916), oil on canvas, 60 x 81cm

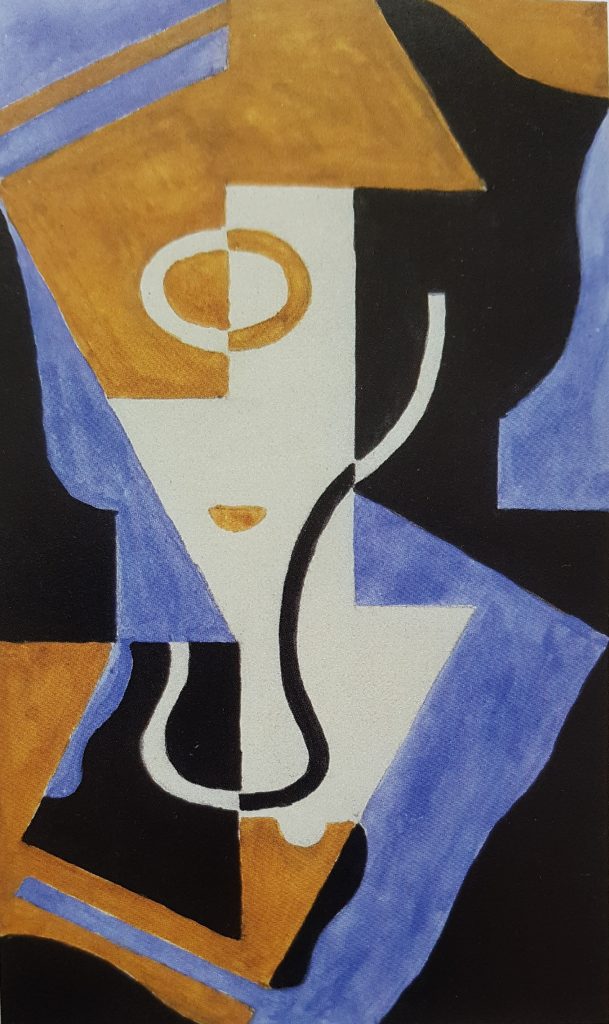

Pablo Picasso, ‘Instruments on a Table’ (1915), charcoal and watercolour on paper, 19.5cm x 16.5cm

Pablo Picasso, ‘Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper’ (1913), printed papers and ink on paper, 46.7 x 62.5cm

Dermee, P ‘Un pochain age classique’ Nord-Sud 2, no. 11 (Jan 1918)

Jameson, F ‘Postmodernism and the Consumer Society’, in ‘The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983-1998′ , London, Verso, 1998

One thought on “John Bunker: ‘New Creation Myths for a Menippean Abstraction, Part One: Cubism and the Kingdom of Thingdom’”

Comments are closed.

All Canadian youngsters grow up reading NOT Shakespeare, but Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism. I did anyway—and it’s nice to be reminded of Menippean satire (and my misspent youth).

Nice to be reminded of Cubism too. Two recent shows in New York also reminded me of Cubism: work by Jonathan Silver at the NY Studio School, and work by David Paulson at the Sideshow Gallery in Brooklyn. Garth Evans did one of his Sculpture Forums on the Silver show: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJhOaombHU1GCZIxKqncI2g?fbclid=IwAR1zLK0YXFBdIchykUFjQLEDkvgfQ-uyOk71jRBk2RMEByFEsITV6UAjXhE. You can find images of Paulson’s work out on the internet too. The nice thing about this work is that it hasn’t been “assimilated”/“historicalized.” It’s just out there. Silver and Paulson know stuff about Cubism. Silver even wrote some interesting things about it for Artnews back in the ‘70s and/or ‘80s. Paulson got his Cubism (indirectly) from Hofmann. But Cubism for these guys is, essentially, just drawing—an exciting way to draw—and not that different from the way Raphael drew.

Worth noting: not everybody in New York thinks the way Ben Davis does: https://www.wsj.com/articles/hilma-af-klint-paintings-for-the-future-review-modernisms-missing-link-1539428400.

I don’t really understand the usefulness of an historical precedent for a new abstraction (whatever that is). Good art historians have always recognized the complexity of what Picasso and Braque and Gris were doing early in the 20th century: the mix of “purity” and “Menippean-ness.” I came across a nice catalog for a 2001 show called “Cubism and Beyond” the other day. In the catalog essay Christopher Green writes with great subtlety about what Braque and Picasso and Gris and Leger were up to after WWI. Things haven’t really changed.