Jillian Knipe: Andrea V. Wright and ‘Flatland’

At ‘Prevent this Tragedy’, a group show curated by DATEAGLE at Post_Institute Von Goetz Art, I caught up with Andrea V. Wright to discuss her installation sculpture through the prism of ‘Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions’. Edwin A Abbott’s satirical novella describes a world of two dimensions through the narrator, A Square. He is enlightened by Sphere, who visits him from the three dimensional Spaceland and eventually convinces him of possibilities beyond his current realm. All ends badly, with Square imprisoned for heresy as the ignorant monarchs of Flatland decree any multi-dimensional preaching as punishable by imprisonment, or, depending on caste, by death.

JK: There’s so much of the book that’s preoccupied with geometry and mathematics; then, towards the end, A Square starts dreaming about Sphere leading him to possibilities beyond his world. Inspired by these new ideas, A Square shifts closer to something emotional, moving into the same sort of zone as that occupied by your work in ‘Prevent This Tragedy’ where the physical interaction with the wall, and observation of its scrapes and marks, seems to lead to imagining stories of what might have happened here.

AVW: Yes, there was a real and intimate engagement with the surface – with every mark and indentation; working around rusty nails and avoiding undercuts so the latex doesn’t rip when you pull it away. On an initial visit to the site I wanted to reference the wall directly, so I had to hire a scaffold, making it a very physical process, starting with the act of climbing up and moving around the higher areas of the space. While I was layering the latex on the wall I was wondering about the bricklayer who had built upwards, whereas I was working downwards. I developed a painting rhythm with my body along the line of the bricks, which became like a system. I refer to this in the title of the piece, ‘Laplace’, as in ‘Laplace Transform’ which is about using mathematical systems to solve physical problems.

Still, it moves beyond simply being about the wall. A lot of the work I’m doing in this space begins flat, but there’s also a lot of conversion. There’s the mixing of the liquid, the liquid being painted onto the flat wall; and then the liquid solidifying, creating a modification in the liquid as it dries, subject to the atmosphere. There there’s the peeling off, so the flat surface moves into space, revealing all these subtle undulations in the surfaces. So there’s a lot of transformation in the process.

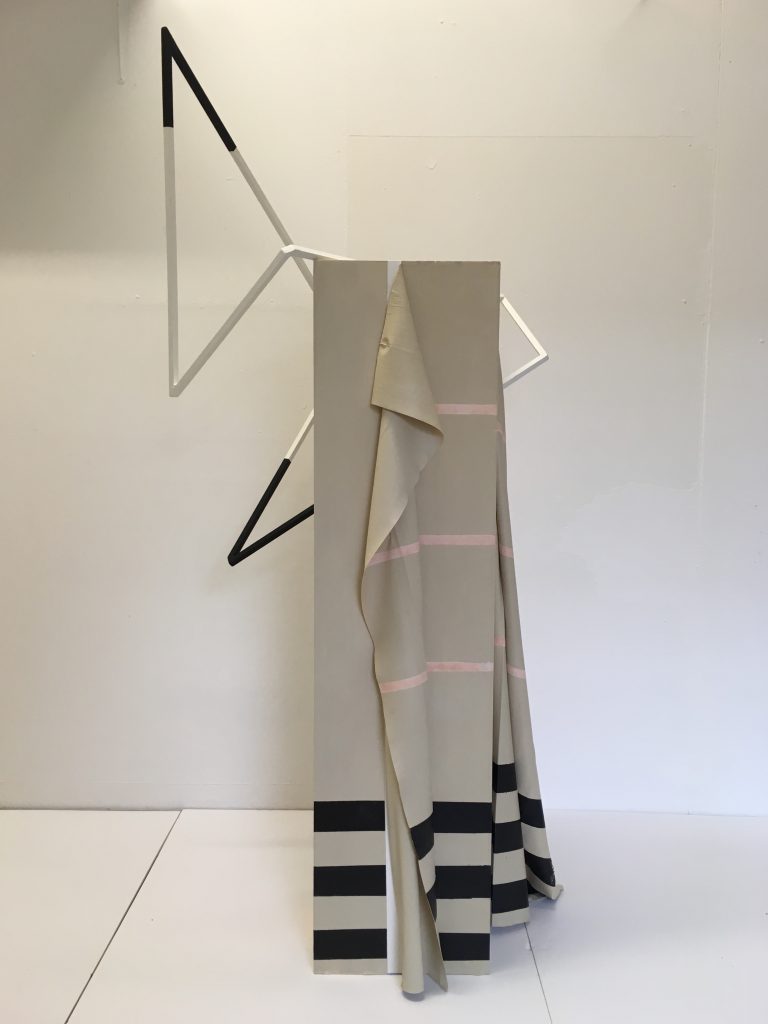

JK: As you describe, the latex of ‘Laplace’ is now half pulled off the wall and lying loosely across a metal frame which looks like it’s held together by a curved bar, which is actually something like tape.

AVW: It’s black ribbon, which I use a lot in my work to create line. Drawing and lines to underpin structure are a very important part of my practice. Using line to define this space is what I brought here, whereas everything else has evolved from me working with the space.

JK: What is particularly interesting about the frame is that we can see with our eyes that there’s two materials here, yet my mind simplifies them to being the same thing in the same way it would all look like metal if we photographed it. So the materiality changes its importance and my perception becomes more important. It reminds me of ‘Flatland’ when Square is trying to describe the third dimension to everybody and he finds it so impossible that when he’s imprisoned he comes to doubt that he ever saw another dimension. This work has that effect on me: where I know logically what I’m looking at, and doubt it at the same time. It’s a contradiction.

Andrea V Wright, ‘Laplace’ (2018), latex, neon light, steel, pigment, paint, tape and found object, dimensions variable, photography by Corey Bartle Sanderson © DATEAGLE ART 2018

AVW: There are elements of dimension and transformation in my work, as there are in ‘Flatland’. Next to the loose ribbon, there’s the illusion that the rigid metal steel rod, which is of the same width, is softening; the ribbon bending is impossible in the same way as in the book, where people believe the mathematical concept described by the square of, say, a cube, is impossible. Even the enlightened Sphere doubts the possibility of a fourth or fifth or sixth dimension.

I also wanted the frame to mimic the drape of the latex. It is there to present the display of the latex itself, which is the main part of the work. It’s a substructure like the substructure of this building which acts as a support for other elements. Whilst there’s a strong geometric element in my work, it’s really important to me to have more fluid elements; so that’s why the ribbon is there, softening the framework. Reconciling these two opposites is an ongoing source of research and experimentation.

JK: It reminds me of your work ‘Vertical Ascension’ which was in the exhibition ‘Make_Shift’, curated by Rosalind Davis at Collyer Bristow. It had those limb-like geometric shapes, and it was very difficult to ascertain what was flat and what was three-dimensional. It included a rectangle of latex in the foreground which looked like a skin in readiness for application, or which had been taken off and was about to be discarded. Without that it would have just referred to architectural and geometric spaces.

AVW: That’s really important to me. I don’t think my work is entirely about system elements or pure geometry, even though I’m very interested in both of these. ‘Vertical Ascension’ was very much about compound angles, which would have been called ‘irregulars’ in ‘Flatland’. Whereas this work is not irregular, it’s a square which has been bent at a 90 degree angle.

Works such as ‘Vertical Ascension’ are much more connected with the body. They’re like a rigid or systemised version of some of those seemingly impossible things that the body can do, or that can be seen in something more organic.

JK: And you were talking earlier about quick drawing, when the model could put their body in a position that’s particularly difficult to hold, creating the most tension between gravity, balance and the angles of the body. You get that sense in pieces like ‘Vertical Ascension’ whereas ‘Laplace’ doesn’t seem to be wrestling with itself. As you say, it’s as if the structure is both embracing the skin and inviting us to consider it.

AVW: Yes, it’s definitely there to serve the other element of the work. It also brings a sense of grounding and definition to the piece. I need it to pull the work together. At the same time I am responding to delineations in this space which have been adapted between the time it was built and now. All these stud walls have been put in and the result is lots of rectangles and squares and divisions. In fact, if we look down at this space from above, it would look like one of the houses from the book where a room is divided according to its purpose or the geometric shape of the occupant who inhabits it.

JK: As we’ve already covered, Sphere appears in ‘Flatland’ and talks about a world beyond two dimensions. This seems to blow A Square’s mind, and he considers possibilities beyond those possibilities and more possibilities beyond that. I see something of that here in the work, starting with the possibility of memories in the walls. It suggests the possibility of memories in buildings. We can then wonder about how we might carry those memories, what sort of mental structure is shaped by our experience of places, and how might they affect the way we manoeuvre our bodies in space.

AVW: Another book I wanted to mention is Bachelard’s ‘Poetics of Space’ and its exploration of the potential of memories in walls and in chambers; and I did feel a sense of connectivity in that wall. I had a sense of compression of time between me making this piece and the person or persons who’d originally constructed the wall, as I felt my way across the brickwork surface. In ‘Flatland’ they talk about how the physical act of feeling is the lowest form of perception but, as a sculptor, feeling is critical. There’s the skin on my hands coming into contact with the wall as I’m painting the latex on, and there’s all sorts of things embedded in it, probably including skin. And if you were able to chemically test the wall, who knows what sort of content would be revealed from the myriad of activities that have been undertaken over the last 100 years, for example. Yet while I’m painting layer upon layer, the work appears as the stories of the brick surface disappear, only for them to be revealed again. It’s as if I’m encapsulating something in time. Perhaps that refers to time as the fourth dimension. I know a lot of scientists, including Einstein, were supposedly influenced by the book.

JK: Coming back to the act of encapsulating and exposing: when you’re peeling away from the wall, you’re not literally revealing what was there before. Some of the substance of the surface has stuck to the latex, some falls away and some is left on the wall. In other words, you’ve changed its composition.

AVW: There’s a sense of hinting. The latex skin doesn’t pick up everything, so it’s not an exact replica, and therefore not a certain fact. More like an impression which allows your mind to imagine the potential of all sorts of things around decay, the passing of time, and other aspects relating to the theme of the exhibition which picks up on the planned destruction of the building. It becomes a remnant and therefore like a relic of its own history. Only to a certain extent of course.

Andrea V Wright, ‘Sheath’ (2018), latex and pigment, dimensions variable (detail), photography by Corey Bartle Sanderson © DATEAGLE ART 2018

JK: Let’s move onto your smaller pieces. Are they tests? Sketches?

AVW: They’re smaller works testing out surfaces. Nothing was relying on their success, so I could be a bit more playful; and people have responded really well to them, perhaps because they lack the formal presentation of ‘Laplace’, the main work. Making them took me around the building, even going into other artists’ spaces, and you can now see a palimpsest or ‘ghost print’ of my process on the walls. This was very much about investigating the space.

JK: ‘Flatland’ details Square’s endeavour to describe a cube. He talks about a line going upwards, not northwards. He is then referring to a transformation and asking, what if we look at an angle from this perspective, rather than the perspective of what we already know? And by implication, what other possible ways are there to look at something? This is done in a way that sums up the intention of any art practice: to ask, what other ways are there of seeing, of existing, of feeling, of making something visible, of bringing something into the foreground? However, when reading ‘Flatland’ I couldn’t help but feel we’re also restricted to an expanse of understanding within our own realm. We are just as restricted, to an extent, as all those sad and sorry shapes in the story who can only see through a very small prism of two dimensions. For instance, if you look at how appallingly women are treated in the story, you could find lots of parts of the real world where women are treated the same way – they must stay indoors, they are not allowed to have a public identity or speak out of turn.

AVW: There are those realities where your life is at risk if you cross the boundaries of your culture. Perhaps the role of the artist is to reveal or highlight unseen dimensions, and what is beyond the boundary. To cross the boundary. Setting a story in an imaginary world gives the freedom to highlight how ridiculous and sinister the cultural boundaries of the real world are. Throughout history men have defined the role of women under the pretence of protection, but it’s actually just a ruse to keep women subjugated.

JK: And it’s always easier, I think, to talk about how terrible it is elsewhere. Yet when we come back more immediately to your work and consider memories that might be held in a building, we can think of the bricklayers and wonder about the conditions of when they worked here. Was there a team? Did they work 12 hour days? To think about that with your process of covering up is like a listening through time; at least, acknowledging people that have come before us as individuals with independent lives.

AVW: My great grandfather was an Irish stonemason. He was in Liverpool and it was a really tough life as far as we can research. Interestingly, at the time when ‘Flatland’ was written, Brixton, where this exhibition is being held, was very much emerging because the railway came here, causing a massive boom amongst developers, who probably used a lot of Irish labourers. Just as there’s a boom now, with buildings like this being knocked down to make way for lots of flats. Every scrap of land is being flattened to create an opportunity for a developer. Hence, ‘Prevent This Tragedy’ is actually history repeating itself.

JK: Let’s go to the pipe. No, it’s a girder. But I think there might have been a pipe there for the metal brace, because there’s evidence of dripping. Anyway, you’ve dressed and undressed the girder.

AVW: I decided to use all the leftover latex – I like to use every scrap, no waste! – to create a multi-coloured piece the height of my reach. ‘Laplace’ is a much more ordered piece. It’s very much systematically ordered with my materials all laid out, timings calculated for layering and drying, with the scaffolding hire determining height. Whereas this girder piece is more instinctive, as tall as my grasp and so it was a little more playful and the outcome looks like a nougat candy skirt for a very tall lady girder.

JK: The practice of dealing with fabrics: folding, unfolding, draping and so on, as at your sister’s fashion company, is very strong through your artwork. It’s as if your experience contributes to the way you function in the world: in the same way as if you were at the dockyards while your Dad was shifting large materials around, like Richard Serra was, it would make sense to work with the precarious balancing of steel.

AVW: Those experiences you take for granted, the repetitions involved in the day to day, they become embedded in your psyche. So something you do, say, two years after an event, takes you back to the time of the event. As an artist I believe it’s very important to draw on your experience. It’s those nuances in your personal history which have the potential to make the work unique and fresh.

JK: I find you can particularly rely on that happening in site specific work, where you’re working with something very physical rather than consciously trying to draw on something emotional. All those emotional aspects and memories and ways of being come out quite naturally because you’re not focusing on them: they’re not contrived, and what is achieved feels familiar, rather than dramatic. But that’s not the case for the viewer.

AVW: By the time I was peeling the latex off the wall I felt a sense of detachment. Then other people bring new things to the work that I can’t see initially.

JK: You told me about Heidi Bucher, whose grandson was in touch with you recently.

AVW: My work is definitely influenced by Heidi Bucher and Eva Hesse, especially with regard to using latex. I wrote about Heidi as part of my MA, and my first major project for the course was made during a residency in Cornwall. I cast the hull of an ordinary fishing boat in the harbour, which baffled the locals. The finished work was encrusted with residue of rust, salt and seaweed. When displaying it, I tried to emulate the shape of the boat, and then realised I had to go with how the material was behaving; and so I hung it as a single sheet. Through the process, the imprint of a three–dimensional boat is transformed into a flat object. Light can really bring the latex to life: so by suspending it as a flat surface, all the fine details were illuminated.

I’ve used latex in many other ways that are not to do with any kind of phenomenology. I’ve wrapped plinths with it, like my works ‘Balance and Obedience’ (2017) in ‘PROTOCOL’ and ‘New Relics’ at Thames Side Studios. At other times, it’s simply presented as a pigmented piece, or just to reveal the drape. Some of those other pieces are more about the balance and poise of the steel structure on the plinth. When I was younger I was really into watching dressage events, so I’ve taken colour palettes and titles from there. There’s often a duality in what I do. I’m continually working towards the fabric and the element of the skin coming together with my need for structure and formal arrangements. I can’t have one without the other. I can’t do just the soft drapery, or just the geometric steel framework. I have to have them both together.

Andrea V. Wright ‘Balance and Obedience III’ (2017), latex, wood, steel, pigment, paint, rubber, 158 x 124 x 82cm

JK: That makes absolute sense when you think about the human body and the fact that we have a spine, along with a complex internal structure that keeps us upright and protects our essential organs. So when you talk about needing to waiver between the two, the softness of the figurative and the hardness of the structure, that seems an important place to be. It’s a paradox. Surely you don’t want to resolve that, otherwise the work is over and there’s no point to doing it any more. To continually wrestle is the point of doing the work; and it wouldn’t come to life without that.

Thinking about these ideas of structure and struggle leads me to consider their opposites, as expressed through Square’s dream in ‘Flatland’, in which he travels down to Pointland, the lowest low, the abyss of no dimensions where it’s claimed ‘that to be self contented is to be vile and ignorant and that to aspire is better than to be blindly and impotently happy’. I thought it was fair warning that absolute contentment is solely self-referential and a dangerous place to be.

AVW: I thought Pointland was referring to something Buddhist, a state of pre-consciousness where you’re only aware of the self. It’s a contrast to how, through making, I’m fully engaging with other people. I’m just about to start the Benson Sedgwick residency1 Benson Sedgwick are an engineering firm who provide sculpture fabrication for the UK’s leading artists and offer a 12 month residency established in conjunction with the Royal Society of Sculptors. so yesterday I was researching plywood and discussing materials with the fabricators. There are phases of my work which bring me into contact with all sorts of people based on their specialist skills, so I get the chance to talk about the work; whether they appreciate it or not doesn’t matter. I also come across a range of opinions when I’m making work in public: for instance, the latex boat in situ, when people watched me work and asked questions about it. After a while they became more willing and more open to accept what I was doing. So when I’m moving between processes of the work and interacting with people, I have a sense of the work becoming fuller and deeper, and it seems to contain more energy.

Andrea V. Wright, Installation view of ‘Prevent this Tragedy’, Dateagle Art, 2018

Andrea V. Wright, Installation view of ‘Prevent this Tragedy’, Dateagle Art, 2018