Painting Beyond Binaries: John Bunker on ‘Frank Bowling Mappa Mundi’ at IMMA

‘The great value of diasporic thought, as I conceive it, is that far from abolishing everything that refuses to fit neatly into a narrative- the displacements- it places the dysfunctions at the forefront. In the imaginary it is possible to condense different persons in a single figure, to alter places, to substitute different time frames, or to slip ‘irrationally’ between them, as dreams frequently do. Montage is its life blood…’1Stuart Hall with Barry Schwarz: ‘Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands’, Penguin Books, 2018, p 171

‘Frank Bowling Mappa Mundi’, which has just finished at IMMA Dublin, charts the development of Bowling’s career from the ‘map paintings’ of the mid-1960s to the early 1990s, where a new weighty materiality and use of collage come to the fore. Although the show’s primary focus is on the development of the map paintings, (a choice reflected in this essay, which will also concentrate on them, rather than other, later works in the exhibition) it also reveals the breadth and depth of Bowling’s ambitions for, and commitment to, the art of painting. Almost by default, this show is daring Tate Britain’s Bowling Retrospective -due to open in May 2019- to match, or surpass, its level of ambition. Indeed, Mappa Mundi is not only ambitious in the range and quality of works on show, but also in terms of the wealth of fascinating archival materials that the highly informative catalogue has made available to all: in particular, Bowling’s writings from the late 1960s, which open up, with acuity and passion, the complex ideas that informed the most advanced arts of the era’s African and West Indian diaspora.

Bowling began painting and writing at a time when the work of black artists was only beginning to be recognized. He became conscious of the threat of marginalization: of being considered only in terms of his skin colour rather than for the specific qualities he brought to painting in response to the challenges defined by late Modernist art. From the off, Mappa Mundi makes it clear that Bowling’s art is not bound by moral imperatives or theoretical posturing, but rather, is enriched and emboldened by the same unapologetic acceptance of painting’s profoundly sensual mediation of human experience that he glimpsed in the work of the old masters that he admired so deeply as a student at the RCA in the late 1950s; and also by the energy, dynamic improvisation, and painterly materiality of the first-generation Abstract Expressionists, whose work he encountered first-hand in the mid-1960s during his extended visits to the USA.

However, what marks out Bowling’s singular trajectory is the distinctly cooler counter-rhythm at work in his assimilation of Late Modernist ideas. After taking up a studio in New York in the late 1960s, Bowling’s natural affinity with his chosen medium- enhanced by technological innovations in acrylic paints- became the means by which he gave expression to both a theoretical, questioning spirit that found succour in his friendship with Clement Greenberg, and in the latter’s pithy prose; and to his burgeoning historical consciousness. Thus, the creative tension in Bowling’s mature work is born of movement in two distinct directions: on the one hand, towards an exploration of the Modernist discourse around an advanced art built on notions of ‘purity’ and exclusions, a bearing down on what were seen, in Greenbergian terms, as the innate properties of painting and the expunging of all that was deemed anterior to its essential qualities; and on the other hand, towards the source of the revolutionary and emancipatory energies that also fuelled his painting at this time: the creative dynamism unleashed by the American civil rights movement, which was giving confidence and hope to artists of colour and colonial heritage who wished to beat out their own individual paths through different cultural milieus, and suggesting new ways to draw on the deep well of experience to be found in a distinctly black interpretation of modernity.

It would be easy to consider these positions irreconcilable: one unapologetically aesthetic, exclusive and reified, the other social, cultural/historical. But these kinds of seemingly opposed territories are never completely sealed off from each other: their barriers are permeable, and perhaps it is the artist’s job to slip between territories, and in the process, infiltrate the ideological positions that underpin them. Bowling’s writings make room for just this sort of manoeuvre: and in so doing, create new spaces for the potential of painting. Weary of being pigeonholed as a ‘Black Artist’ both by the white elite of the art world, or by those within black American artistic communities that viewed Modernism as a white-dominated discourse, and were looking for exemplars of what might perceived as an essential black identity, Bowling, in these texts, asks: on what terms do we attempt to define black art?

‘What precisely is the nature of black art? If we reply, however, tongue-in-cheek, that the precise nature of black art is that which forces itself upon our attention as a distinguishing mark of the black experience (a sort of thing, perhaps, only recognizable to black people) we are still left in the bind of trying to explain its vagaries and to make generalizations. For indeed we have not been able to detect in any kind of universal sense The Black Experience wedged-up in the flat bed between red and green: between say a red stripe and a green stripe.’2Bowling, F ‘It’s not enough to say “Black is Beautiful”‘, Arts Magazine, April 1971. Quoted in ‘Frank Bowling: Mappa Mundi’, ed. Enwezor, O, pp207-209. Prestel 2018

Bowling’s painting is informed by Modernist medium-orientated experiment and self-reflexivity. In its implicit questioning of the viability of narrative-based, illustrative painting, Bowling’s Modernism acts a critique of essentialist narratives of origins or ‘Blackness’ as put forward by the social realist and political painting of the time. For Bowling, Modernism acts a liberatory force, breaking down outmoded notions of identity by harnessing paint’s protean nature in the service of an art of constant change and discovery.

‘…It is clear that modernism came into being with the contribution provided by European artists’ discovery of and involvement with African works, and their development of an esthetic and a mythic subject from it. But the point I am trying to make concerns the total “inheritance” which constitutes the American experience and that aspect of it with which black people can now (perhaps they always have) fully identify, due to the politicization of blackness. It would be foolish to assume, as some do, that the development of modern art through the contributions of African ancestors is solely the property of blacks, for it is evident that the filtering process must include white consciousness.’3Bowling, F, ibid.

It must be understood that this approach is not an attempt to see Modernism as a means whereby racial difference and the realities of racism might be circumvented; but rather, through his painting and writings at this time, Bowling offers a critique of the cultures of painting, and of notions of ‘black art’; and his exploration of the slippages and gaps in signification between his modernist view of painting and his diasporic New World perspective finds its counterpart in Hall’s argument, that race as a classification of human type is a social construction which articulates itself through power relations: ‘Race is a discourse; that operates like a language, like a sliding signifier;(…) its signifiers reference not genetically established facts but the systems of meaning that have come to be fixed in the classifications of culture.’ 4Hall, S, ‘The Fateful Triangle: Race, Ethnicity, Nation’ Edited By Mercer, K. Harvard University Press 2017, p 45.Both Bowling and Hall challenge, in their respective contexts, the idea of an unchanging definition of the sovereignty of self as defined by notions of origins.

We have become used to the idea of artists appropriating aspects of the Western canon and encoding it with new messages that speak to the excluded or the ‘invisible’ colonial/post colonial subject; yet any attempt to frame Bowling’s work only in these terms would fail to do justice to the sheer ambition of his painting. To stand in front of a group of three map paintings at IMMA, each one between five and seven metres in length, is to realise how entirely integrated and unified they are: each one seems to exceed the sum of its parts in terms of its new, singular set of visual cues, and in terms of its particular colour register, which in each case carries its own distinct emotional timbre and level of intensity. At first glance, the colour of Dog Daze (1971) appears to be acting as an autonomous force; but it soon becomes clear that these freewheeling, blazing, pinky-reds and hot yellows are carefully orchestrated around a set of internal structures over which the colour is flooded. By using the natural geometries of the root rectangle derived directly from the dimensions of the canvas itself, the map stencils emerge and recede in carefully choreographed rhythms. Intense, soaked-in colour pulls the eye into the crevasses delicately traced out in the fragile latticework of sprayed stencils, bleeding back into the very fabric of the canvas. These multifarious shadow-plays of imagery are simultaneously presences, absences and erasures; they are at once afloat and submerged in the pooled pairings of hot pinks and yellows, or softer reds and deep burgundies, only to be further intensified by outline traces of acidic greens and yellows. Bowling’s stencilled appropriations of iconic land masses are seemingly at odds with the conventions of colourfield painting and notions of a ‘pure’ abstract art; but Bowling’s Modernism asserts discursive experimentation over dogmatic rulemaking. He deploys virtuoso effects of sustained visual intensity and startling painterliness, but also plays painterly conventions off against each other until something unprecedented is achieved. These images and erasures would be unimaginable in any other medium; and were, arguably, unachievable by any other artist of that era using the language of Modernist abstraction.

Bowling was born in what was then British Guiana. He is a part of the Windrush generation, only realising his calling to be an artist once here in Britain. The map paintings seem to stand as a visual equivalent to Stuart Hall’s notion of the ‘…value of diasporic thought’, opening up abstraction to the black diasporic experience and making a claim for a Modernism that is singularly well attuned to exploring that experience, whilst simultaneously expanding and enriching the Modernist syntax in abstract art on Bowling’s own terms; and he continues to this day to ‘make it new’. His breakthrough paintings could not have existed without the discoveries of Rothko, Newman and Still; nor without the technical innovations of Pollock, Frankenthaler and Morris Louis; or even, arguably, Johns’ Duchampian appropriations of the everday: but they are transformed by Bowling’s determination to confound convention, not for its own sake, but in order to get beyond the binaries: abstraction versus figuration; the aesthetic versus the political; appropriation versus gesture. Bowling knows that the artist must find ingenious ways to move their precious cargo, the art, back and forth, over, under or through these artificial borders of imposed limits to identity and thought; and that in so doing, the art will become all the richer and more powerful due, in part, to its contraband nature. It leaves behind dry intellectualism, romantic rhetoric and political posturing and, in the process, like anything truly moving, gets under our skin: whatever colour that skin might happen to be.

Stuart Hall again: ‘The emergence of ‘the modern’ has never been an uncontested or incontestable narrative: we must also recall the role which what was not modern- the so called ‘primitive other’- played in breaking the mould of contemporary thought and representation, releasing the modern from its nineteenth century confinements into new modes of perception and relationship (…) I understood this better some decades later when I first saw, in the 1970s, the paintings of the great Guyanese abstractionist Frank Bowling, who lived most of his adult life in Britain and the US, and whose stunning corpus of work was for a long time- and to some extent still is- without proper recognition in Britain. Bowling once memorably remarked, to the astonishment of many radical young black artists in the audience, that ‘The black soul, if there is such a thing, begins in modernism.’ What a wonderful way to think!’5Hall, S, with Schwarz, B: ‘Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands’ Penguin Books 2018, pp 124-125

Hall, S ‘The Fateful Triangle: Race, Ethnicity, Nation’ Ed. Mercer, K. Harvard University Press 2017

Hall, S, with Schwarz, B ‘Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands’ Penguin Books 2018

‘Frank Bowling: Mappa Mundi’ Ed. Enwezor, O, Prestel 2018

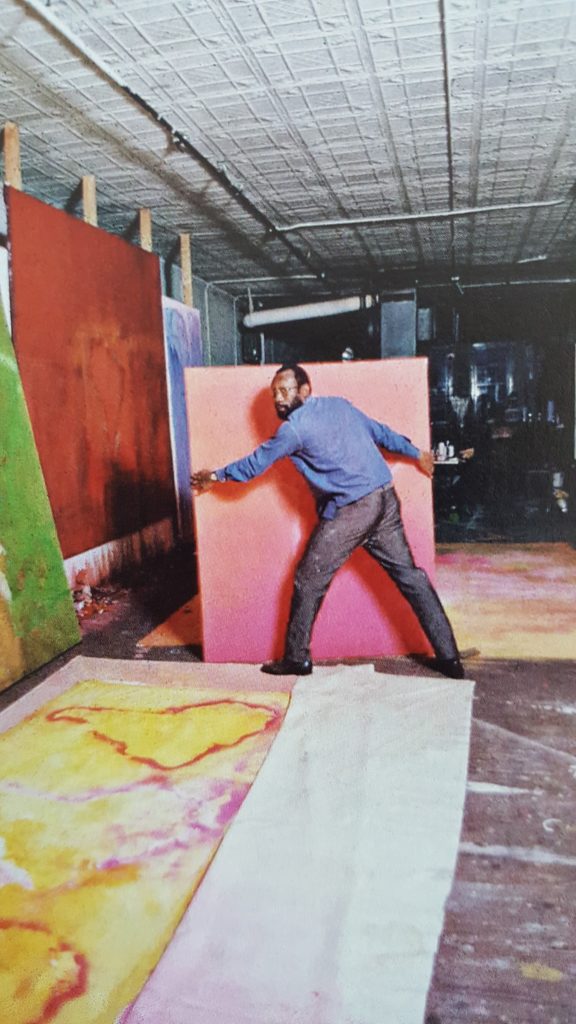

Frank Bowling, Installation view of ‘Mappa Mundi’, IMMA, 2018

2 thoughts on “Painting Beyond Binaries: John Bunker on ‘Frank Bowling Mappa Mundi’ at IMMA”

Comments are closed.

FYI (from New York): https://hyperallergic.com/459314/frank-bowling-make-it-new-alexander-gray-associates/

Interesting article or essay, please let me know who the author(s) for reference purposes?