Jai Llewellyn writes on Rose Wylie

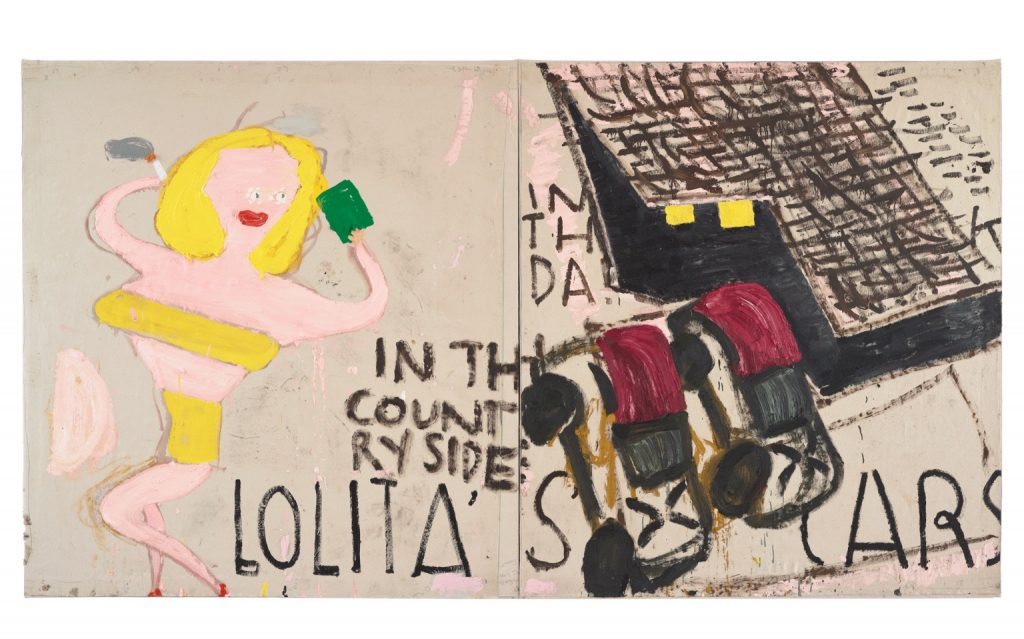

Rose Wylie is not someone I had previously paid much attention to, but with her name cropping up all over the place at the moment, I thought that she must deserve some attention. I may be late to discover what Wylie has to offer: seen through a screen, (as is often the case these days) her imagery did not at first inspire instant love; but despite that, there were aspects of the work that caught my eye, warranting closer inspection. ‘Lolita’s House’, the show at David Zwirner, in London, was the first time I’d seen the work in the flesh; and those inklings I’d previously had, about how the paintings were put together, became more vivid in front of the work.

There’s a beautiful honesty to the construction of the paintings: the canvas is crudely cut and laid down, large sections are pasted over one another and re-painted, loose threads are deliberately left to hang, there are notes of measurements all around the periphery of the paintings left for all to see. Wylie writes, “…I use strips of canvas as collage on work that has gone wrong, so I think if you repair something you should see the mend, give respect for the work done.”1Fiona Maddocks, (2016), In the studio with Rose Wylie, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/in-the-studio-with-rose-wylie-ra

The paint is generously applied, and slapped on thick. There are drips and splashes, smears and smudges all over the paintings, which are not apparent until you are face to face with them. They are undoubtedly painted quickly and with tremendous vigour, perhaps in the knowledge that time is not on her side. I am not suggesting that it may all come to an abrupt end; though there is a feeling of urgency from a woman in her later life wanting to achieve as much as possible. Whether this is the case or not, she has clearly been prolific in the few years since rising to stardom.

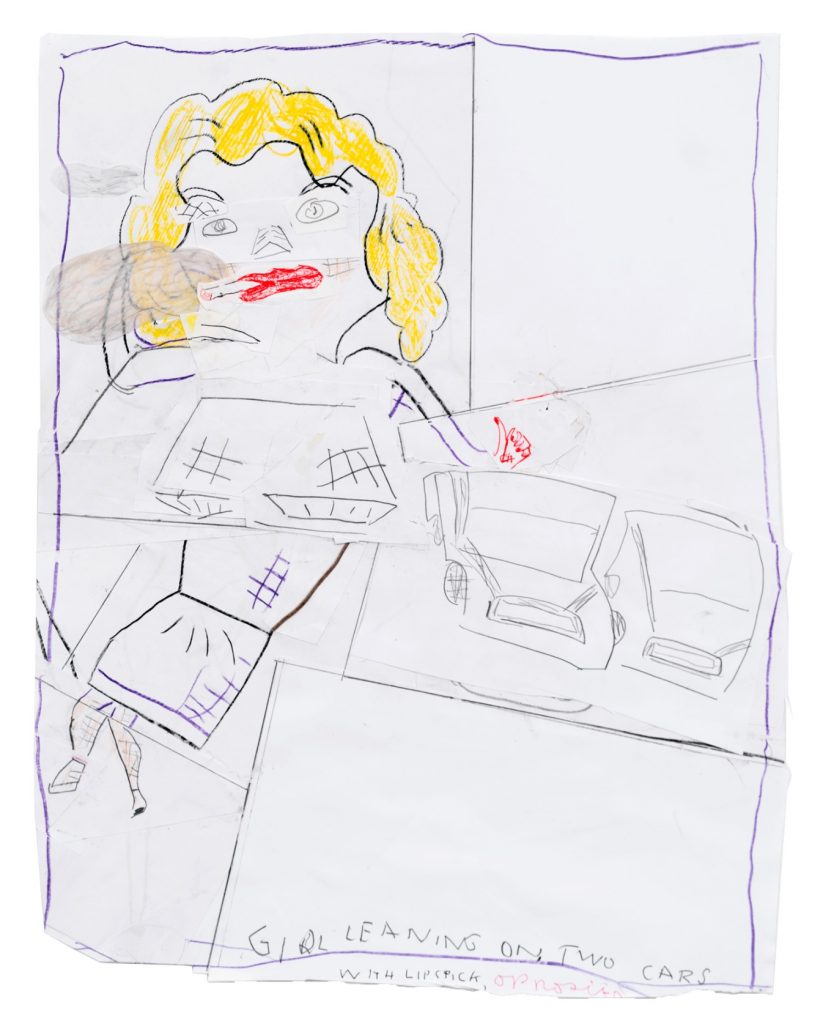

In a couple of the paintings you can plainly see the initial outline, sketched in paint and then nonchalantly filled in with colour, giving form to her characters, figures, animals or objects. She treats an eight-foot canvas no differently from a page in a sketchbook. Nevertheless, she does work from preliminary drawings, and there are a few examples in the exhibition: these are made in coloured pencil on cheap A4 paper, and employ the same cut-and-paste methods as the paintings. You could be forgiven for thinking that this all speaks of a slap-dash, cut-and-shunt approach, but there is more to her methods than that: there is a sensuality and delicate sensitivity in her use of materials and the language of paint. For her, the canvas is just as important as the paint, and its every aspect is considered. The raw canvas is given great respect and is allowed to shine through in most of the paintings, with large areas left blank, allowing the purity of the paint and colour to sing. Wylie states,“ The flexibility of leaving bare canvas and ‘floating’ imagery allows these regroupings and linear-continuations to happen easily in a picture hang, while also permitting individual paintings to keep their own particular, independent identity.”2Anna K Hanchett, (2014), John Moores Painting Prize, https://purejudgment.wordpress.com/2014/09/22/john-moores-painting-prize-2014/

Rose Wylie, ‘Girl Leaning on Two Cars with Lipstick’ (2018),

coloured pencil, pencil, and collage on paper, 46.8 x 36.9 cm

It seems she paints these monumental canvases unstretched, and then glues them down onto a fresh piece of canvas before stretching them. This is never going to be an exact science, and Wylie does not try to hide any practical problems in their making; on the contrary, she makes a point of them. At first this appears to be an ad hoc procedure, with the edges and corners never quite meeting and nothing being perfectly square; but the more you look, the more you realise every decision has been carefully orchestrated. From the colour of the pencil registration line where she has glued a new piece of canvas over a ‘mistake’, to the slight tilt of the image, to the way the canvas caresses the edge of the support and a bit of something is cut off or slips off stage, to her aggressive cartoonist’s drawing style, everything adds to the overall feeling of slight uneasiness, which keeps you on edge, like the suspense in a Hitchcock thriller. For me, the way the paintings are made is as powerful as the imagery itself. I found myself getting lost in the details: for such expansive works, she really makes you pay attention to every little decision; and because of this, I almost forgot about any suggested narrative. They are beautiful objects in their own right, and can be appreciated simply for their sculptural qualities and use of material. Wylie herself says, “The painting isn’t about something. I think lots of people don’t understand that. They think it’s the message, which it isn’t. The message is the painting. The painting is the painting.”3Edward Lucie-Smith (2017), Forget Age and Gender, the Message is the Painting, http://www.artlyst.com/reviews/rose-wylie-forget-age-gender-message-painting-edward-lucie-smith/

This might seem a strange statement, when the paintings appear to be trying so hard to communicate messages, with specific characters, names, times and places; and with texts, to boot. However, as one tries to make sense of the work, it quickly dissolves into a soup of random thoughts, colours and paint. The paintings are in fact almost abstract: as one looks, recognisable images break up and are broken down, and figurative elements become shapes and motifs. Relationships of colour and line dominate, and the entire painting is in constant flux. Natural Born Killers Close up is a good example of this, and is unusual amongst the group, being predominantly black, with little of the canvas left unpainted. It’s unclear what is part of the car and what is the figure: there is just a complex weaving of lines and colours, waiting to be deciphered. The only clue -apart from its title- that this painting depicts anything, is the disjointed figure whose orange hair and beard are only separated by an oversized pair of wraparound sunglasses.

Easy visual comparisons can and have been made between Wylie and painters such as Basquiat and Guston; although it is also possible to detect a direct lineage from post-war British abstraction, in particular Roger Hilton, whose drawings bear a striking resemblance to Wylie’s, or Sandra Blow, who was just ten years older than Wylie, and became an honorary Royal Academician at the same time that Wylie and her partner-to-be, Roy Oxlade studied there in the early 70’s. Blow worked in a very similar manner to Wylie, combining collage with painting on an equally epic scale. As well as Hilton, Blow and Wylie herself, many artists of the 50’s and 60’s were of course influenced by the introduction of the Abstract Expressionists to Europe, via the Tate’s large show of their work in 1959; Wylie’s contemporary Basil Beattie, who later rejected pure abstraction, recalls seeing the exhibition: “I came away with the feeling that Abstract Expressionism was what I would actually call ‘realism’”. He goes on to say, “…there was a vividness and intensity of experience (in) witnessing those canvases…the work reached a height of ‘real’ experience”.4Aimee Parrot, (2016) ‘AbEx Now’, RA Magazine, (Winter), p.55 This idea of realness is an interesting one: questions about what is abstract in painting, and what is ‘real’, prevail; and if they are, in fact, one and the same thing? As Wylie has said, her paintings are not about anything; the painting is the painting. Therefore anything ‘real’ in the work only comes from her direct experience, and her scrupulous treatment of, the paint itself. Wylie stays true to her materials, allowing them to be at the forefront and to take precedence over any ‘image’. The best of Wylie’s work certainly possesses this realness in abundance.

Both Wylie and Beattie have a confident directness in their paintings and a broadness of brush, dictated by the paint and the way it demands to be handled. The paintings have a physical presence that allows the viewer’s experience to be guided by their body rather than their mind. Although Beattie’s language of architectural forms, constructed from elemental shapes, lends itself to known abstract tropes, Wylie’s subjects are painted in such a way that are perhaps are no less abstract. And regardless of the imagery or motifs used, both artists try to evoke their own memory of place or emotion, of things that have no visibility, rather than abstracting from something seen. Just as a Rothko’s work was misunderstood as depictions of sunsets, a Wylie might be misunderstood as being about a day in the life of a girl called Lolita.

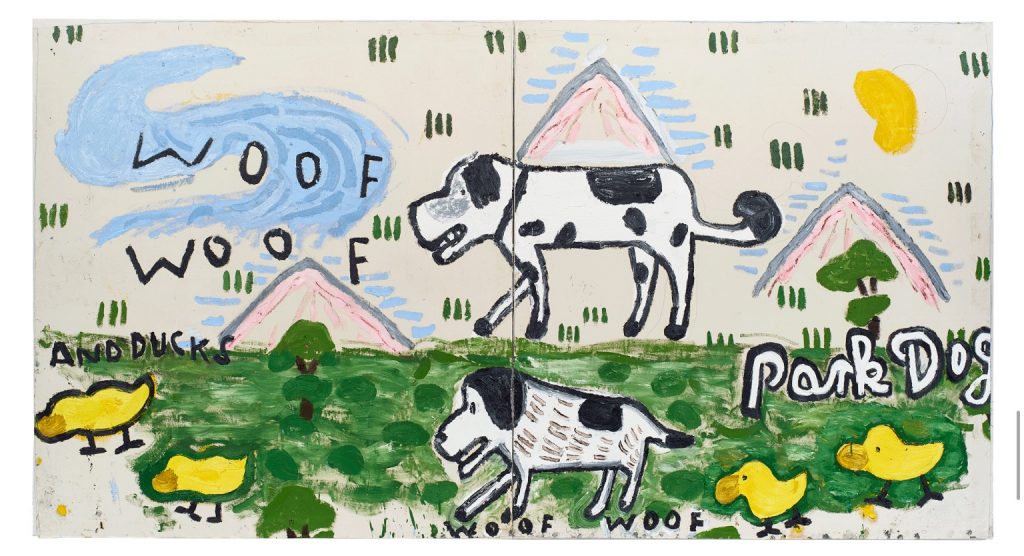

Wylie’s paintings are hard to pin down or pigeonhole. They are the product of a lifetime’s worth of experience and influences, delivered to the canvas with the lethal marksmanship of a Tarantino assassin, by Wylie’s choice of weapon, the loaded brush. There’s a lot going on in the paintings. Sometimes, for me, they can be too busy and don’t always hit the mark, appearing too slapstick, and occasionally slipping on their own comedic banana skin. “Park Dogs, Woof Woof” is one, I feel, that falls short, with the imagery dominating, and verging on the cartoonish or the illustrative; it is almost a pastiche of her own work. Nevertheless, whether she succeeds or fails, it is her dance along the fine line that separates the two outcomes that makes these paintings so exciting.

It’s a shame that she lived so long only in the paintings of her late husband, Roy Oxlade, and that for many years she was not so proactive as an artist in her own right. I don’t think I’m being overly cynical, knowing how fickle the art market is, to say that it took his death, or at least the end of his career, for her to be allowed a place in the spotlight, working in front of the canvases instead of appearing in them. It may be the case that they shared ideologies: there was undoubtedly mutual respect and common ground in their approach to painting. But now, at 83 years young, Rose Wylie is speaking in her own voice.

Rose Wylie, ‘Natural Born Killers, Headlights (Film Notes)’ (2018), oil on canvas, 183 x 164 cm

Rose Wylie, Installation view of ‘Lolita’s House’, David Zwirner, London, 2018

Rose Wylie, ‘Lolita’s House, Plaster Pink’ (2018), oil on canvas in three parts, 185 x 530cm

Rose Wylie, ‘Yellow Girls 1’ (2017), oil on canvas in two parts, 183 x 340 cm

4 thoughts on “Jai Llewellyn writes on Rose Wylie”

Comments are closed.

In depth and thoughtful, as well as thought-provoking review / essay…an artist I didn’t know but now am pleased to have been introduced to. Interesting comparisons to both Hilton, who talked of “swinging in the void”, as well as to Sandra Blow

Very informative and interesting review Jai. I was already a huge fan and I identify massively with her style and basically everything. I can fully appreciate her staying out of the limelight until now as a woman and a mother. I thought your take on her work was very sensitive and has helped me to further appreciate it if possible.

This is NOT “total tosh”—as Robin Greenwood Tweeted alliteratively—and ambiguously–recently. I guess he meant both the show and the writing were nonsensical. I haven’t seen the show. Has Robin? I have seen a little of Wylie’s work though. It makes sense to me. And Jai’s writing is obviously terrific—gently calling attention to the abstract dimension of what an old-fashioned abstract artist might take for “figurative” art. The sooner abstract artists get over their fear of the figure, the better. This review is a step in the right direction.

Art doesn’t come out of nowhere. I haven’t yet caught a Rose Wylie show and look forward to doing so. I’m pleased for her success. There is absolutely no reason why figurative art should not be challenging and exciting. I was a friend of Roy Oxlade for many years, and although of a gloomy disposition, the effect he had on his students was electric. But then he came, like my teacher John Epstein, out of the Borough group. This was David Bomberg, teaching Dennis Creffield, Epstein, Oxlade et al. A real, viable, expressive tradition, which is rare in english figuration and utterly absent in Bacon and Freud (but not Kossoff and Auerbach, who may have participated at Borough.) I really look forward to seeing this work.