Sam Cornish: Six Questions for Sara Naim

What are the differences between traditional photographs, whether digital or analogue and what you call your “abstract quasi-photographic imagery”?

Ben Tufnell actually labeled this, which I quite enjoy! They differ because none of the works in my Reaction show at Parafin are made using a photographic camera. Even the polaroid images are not made with a polaroid camera. I used the polaroid as a method to obtain a chemical reaction between light and the chemistry of the film, which I then scanned and magnified. The shape of the works also set them apart from traditional formats. The fact that photography is relatively new compared to other art mediums, means that breaking its own framework might be happening more quickly than with other mediums. The past decade has seen many photographers creating self-referential work that comments on the medium itself. It’s definitely a strong force within my practice. I think photography is a medium used not only for what it can say, but also because of how it can say it. I studied photography at LCC for my Bachelors, and after the first day of class I wanted to know why images are shaped as a rectangle.

Can you define what you mean by “reaction”?

The show consists of digital and analog glitches, as well as chemical reactions. I consider these all physical manifestations of a changing state. Non-statically, almost emotively, responding to their new position or way of being. For my last solo show, each artwork was named based on a physical manifestation of a human emotion: Blush, Tremble, Twitch, Chill, Pallor, Sweat, Tense, Shudder, Choke. These emotions react with the internal body and, as the face turns red or the body perspires or shakes, become externalized. A ‘reaction’ is like a word within a language. This idea began my infatuation with a ‘reaction’ as a conceptual notion and as a physical outcome.

On another note, the chemical definition of a reaction are when bonds between atoms are broken and created to form new molecules. My works aren’t politically loaded, but being from Syria, that notion of needing to break something in order to build something new is really relevant to me. I will be carrying this notion forward in my upcoming show The Exoticism of Foreign Speech in Dubai’s The Third Line next January.

Do you consider it useful for the viewer to know the specific sources of your imagery?

At some point, yes. If I could dictate how a viewer negotiates the space, I would have them view the works prior to reading the text, and then encounter the works again. It’s important to have their imagination triggered, and sometimes when they know too much about the source, it can become too didactic and technical. And that’s really not my point. I do however think the works open up when you understand that the seemingly foreign thing you were looking at is actually a glitched image of a dead skin cell. That discontinuity between the viewer’s expectation and what they know can be the very thing that challenges their perception.

The thick plastic you use is very physical compared to the ethereal nature of your images. Can you explain the intent behind that? Is it to create a distance from the viewer? Or to physically or psychologically “protect” the image? Or is there another impulse behind it?

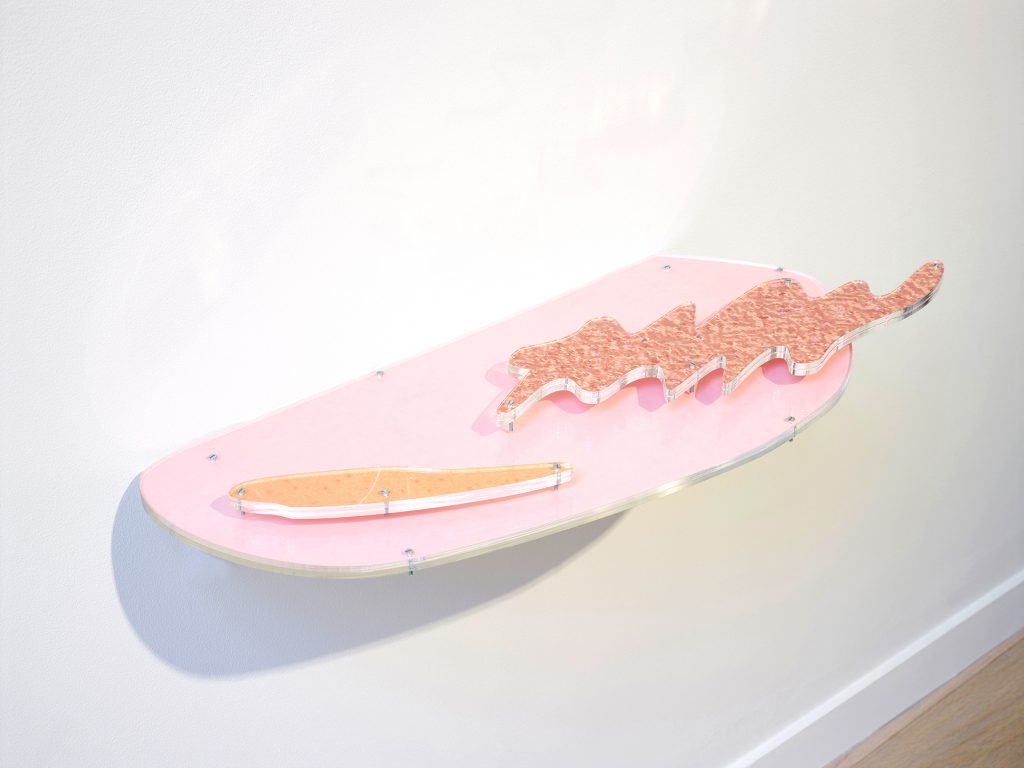

It’s a material that allows me to shape the images in the way that they need to be shaped. I’ve always opted for glass, or in this series plexiglass, which creates reflection, because having worked a lot in the physics lab with sample slides, I find this quality reminds the viewer of ‘looking in’, and they become more clinical observers. I like this imposed role, and it especially suits the microscopy images.

There is a question in the press release: ‘Can shape be considered an object in itself?’. This seems to me to echo American criticism around modernist painting of the sixties, the shaped canvases of Frank Stella or Kenneth Noland. Do you consider your work related to this legacy, or to other aspects of modernist abstraction?

My absolute hero is Jean Arp, so yes, I think abstract modernism has certainly ‘shaped’ my work. Although his forms are three-dimensional and have inherent shape, I think they go beyond that. The silhouette of his shapes somehow become their own objects, and the shapes within his 2-D work also posses object-like qualities. The right tension between the rim of the object and its content can create this shift, so that a shape becomes an object. And I think this is what Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland and also Kandinsky were doing. Kandinsky’s forms within his paintings are like small objects that have been flattened. I try to adopt this mentality but in reverse, by unpacking a two-dimensional image.

Sara Naim, ‘Spasm; Lost Connection of a Blood Cell’ (2018), c-type digital print, plexiglas and wood, 117 × 103 × 4 cm

Have you seen the Tate’s Shape of Light exhibition?

Not yet, I live in Paris but I come up to London next week for the last few days of my Reaction show, ending on May 19th, so I will check it out then! I’ve heard good things…