Susan Roth: Big Shoes

‘Art is everywhere you look for it.’ El Greco

As one foot follows the other, images of memory appear even when there seems to be no obvious or even meaningful connections between them. The paradox: whatever our reality is, our observation is not the full story; space and time do not inhere in reality. This is what I want to address: how an artist bound by their gifts, stimulated by reflections, becomes a voice of the special awareness of our time. Pushing aside doubt, which often slips easily into modern misery, I am here before you again. In this there is no mystery: I want to be understood.

Toni Morrison has this to say about loneliness: that it is not solitude, a necessary component of art, that brings it on: rather, it is not being understood. This essay of mine, like the others that preceded it, revisits experience, memories, hoping to create a further, layered experience, both yours and mine; hoping too, as I search, that I might re encounter that elusive criterion by which I measure experience: the sense of wonder. In this, I am more a hunter than a critic.

Art is not separate from anything else. What follows is a prismatic commingling of then and now.

My first visit to Clement Greenberg’s New York City apartment and resultant linking-together in my thought of two great artists, continue to inspire: experience sets the standard and what we value most is important for us to achieve.

What set this in motion was a trip to New York City, the first trip since COVID, during which a deep anxiety was arriving in waves. It would be memory, I hoped, that would dispel the painful present: before doing any other looking we would visit the Frick installation at the Breuer Building to view my touchstone, El Greco’s ‘Vincenzo Anastagi’ (I have written elsewhere about my profound connection to this painting.) Perhaps revisiting this work would inspire me to come back to my own in the same spirit as where I left off; that somehow, the time away from looking would not register as loss. It is the feeling of constant renewal bestowed by repeated returning to work that inspires that creates in us a sense of personal history. As with bonsai, appearance barely changes; these re-viewings reinforce a different conception of time, de-emphasizing the idea of time’s progress. Time’s passage is recorded as care. This ritual of devotion allows for each visit to offer different interpretations reminding us that change is life’s only constancy.

I had not given much thought to what seeing the Frick collection uprooted and installed at the old Whitney would be like. Entering this more public space where no traces would be found of the private life of the collection’s original owners that the old installation provided, I wondered: would I feel a nakedness of this presentation. Since ‘Vincenzo Anastagi’ was now in effect in two places at once, would it have a split personality like Poe’s great metaphor, ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’?

Coming upon it unexpectedly, I was stunned. Laughing loudly, I blurted, ‘It’s so big! I had no idea!’ How had I missed its scale? The picture’s force could not be circumvented. All this time I had believed the painting was unfolding, blooming, sharing its secrets with me. On this day, in that place, I understood it was me, the viewer, that was in flux. Art is discovery.

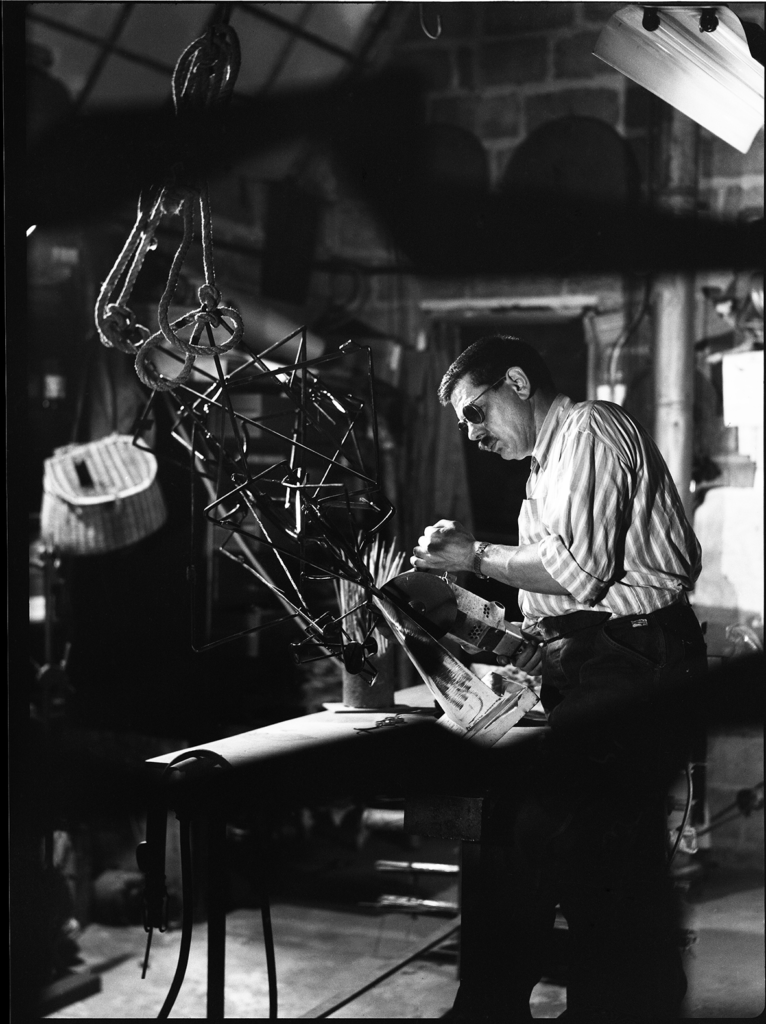

We, my partner, Darryl Hughto and I – were visitors to the city, squeezing in too much. This limited time compels a wide focus; the better to survey centuries, that I might locate myself within a tradition. Place implies space; on this path of creativity no artist is alone. Next on this excursion, the Yares Gallery, where, turning a corner, I came upon David Smith’s ‘Voltron XXIV‘ of 1963. In an instant, I am lost in reverie. Memories, feelings I could not ignore, flooded in. It is 1974 and I am making my first visit to one of Clement Greenberg’s gatherings, his ‘Drinks at Five’.

I had heard of these gatherings and was very excited. We had seen so much art that day and I was ready to be asked my opinion. I had already witnessed Greenberg’s curiosity and inclusiveness when I was among a small group of Curator Henry Geldzahler’s helpers that were invited along when Greenberg visited ‘New York Painting and Sculpture 1940-1970’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I did not doubt that I would be included in the conversation.

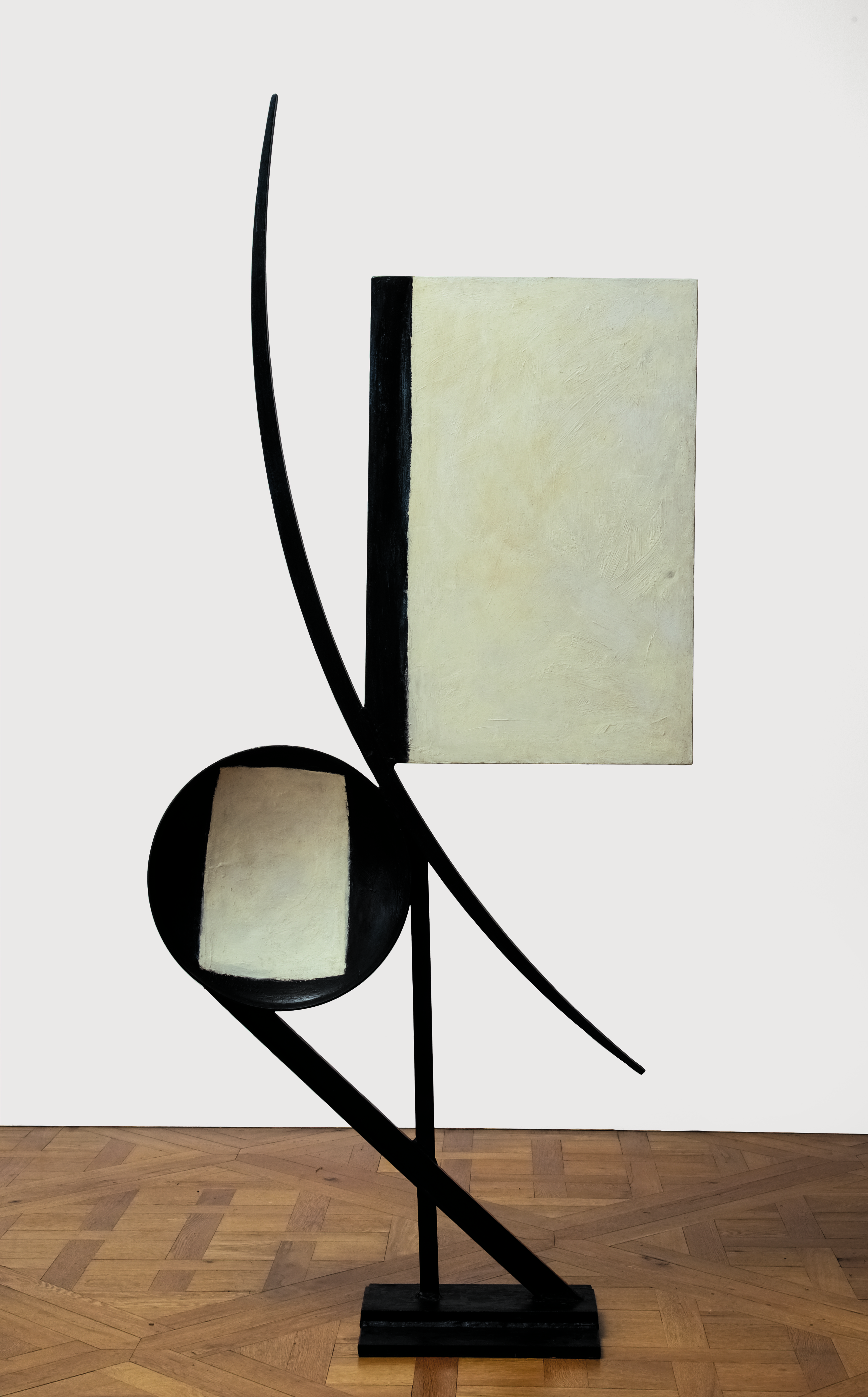

We arrived early at Greenberg’s apartment. ‘Help yourself to a drink and join us!’ he hollered from a room beyond as we let ourselves in. Entering the living room, the conversation halted and Greenberg introduced us to John Kasmin, the English art dealer, as his friend, Kaz. They immediately continued exchanging thoughts on Mondrian. We sat. My eyes were straight away glued, locked on, to Smith’s ‘Voltri-Bolton XXIII’ of 1963, there in the living room next to me, big, bold and beautiful. I found myself wondering whether Greenberg lived within Walter Benjamin’s aphorism: ‘To inhabit means to leave traces.’ The notion that our private home is where we leave memories, making them our own, gaining possession; something akin to inheritance, hoping to understand our dialogue with our objects.

I heard my name. ‘Miss Roth, what do you think of Mondrian? What’s your take?’ I remember bringing in Smith, relaying the excitement I felt. I declared myself a fan of both artists. Whatever it was that I exclaimed, both men laughed.

And here I am now, like a Michael Ondaatje character ‘here to re-witness earlier events to work out how these experiences made me who I am.’ And conditioned how I see.

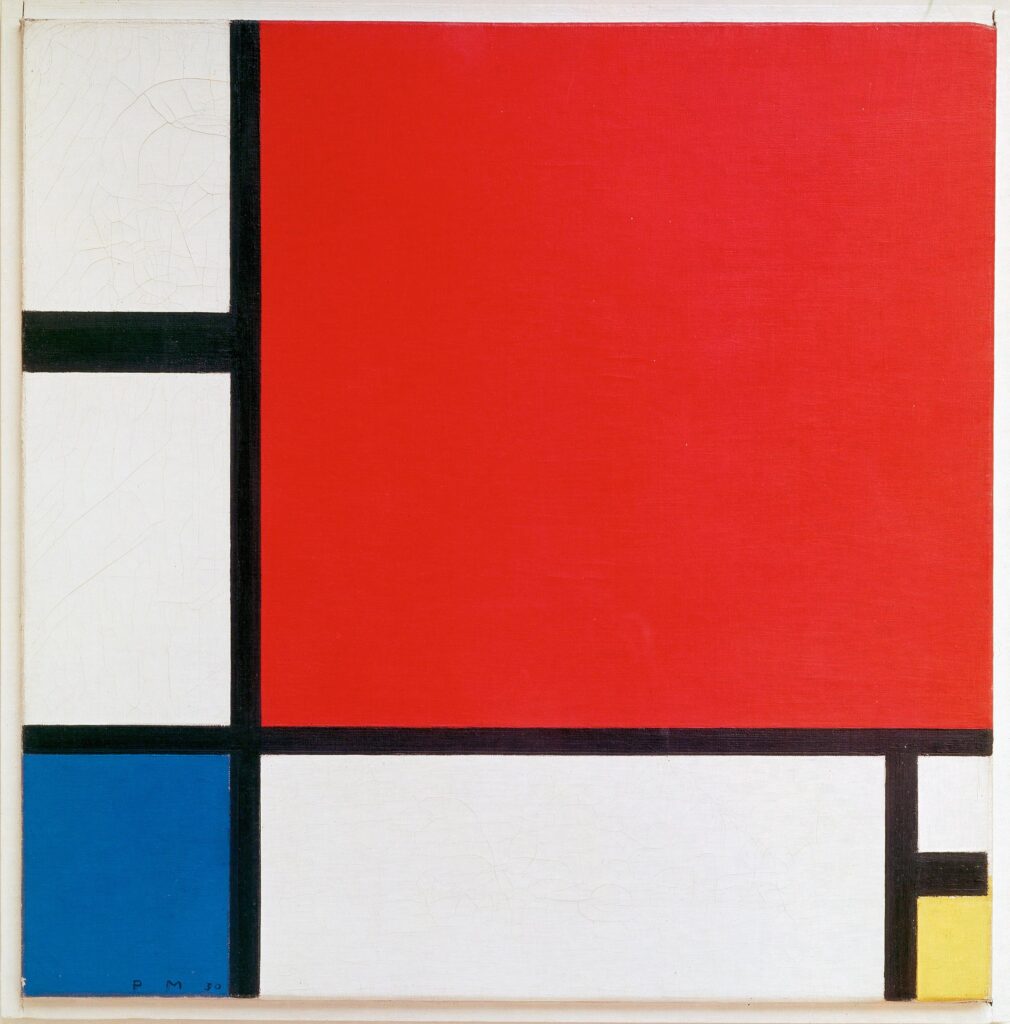

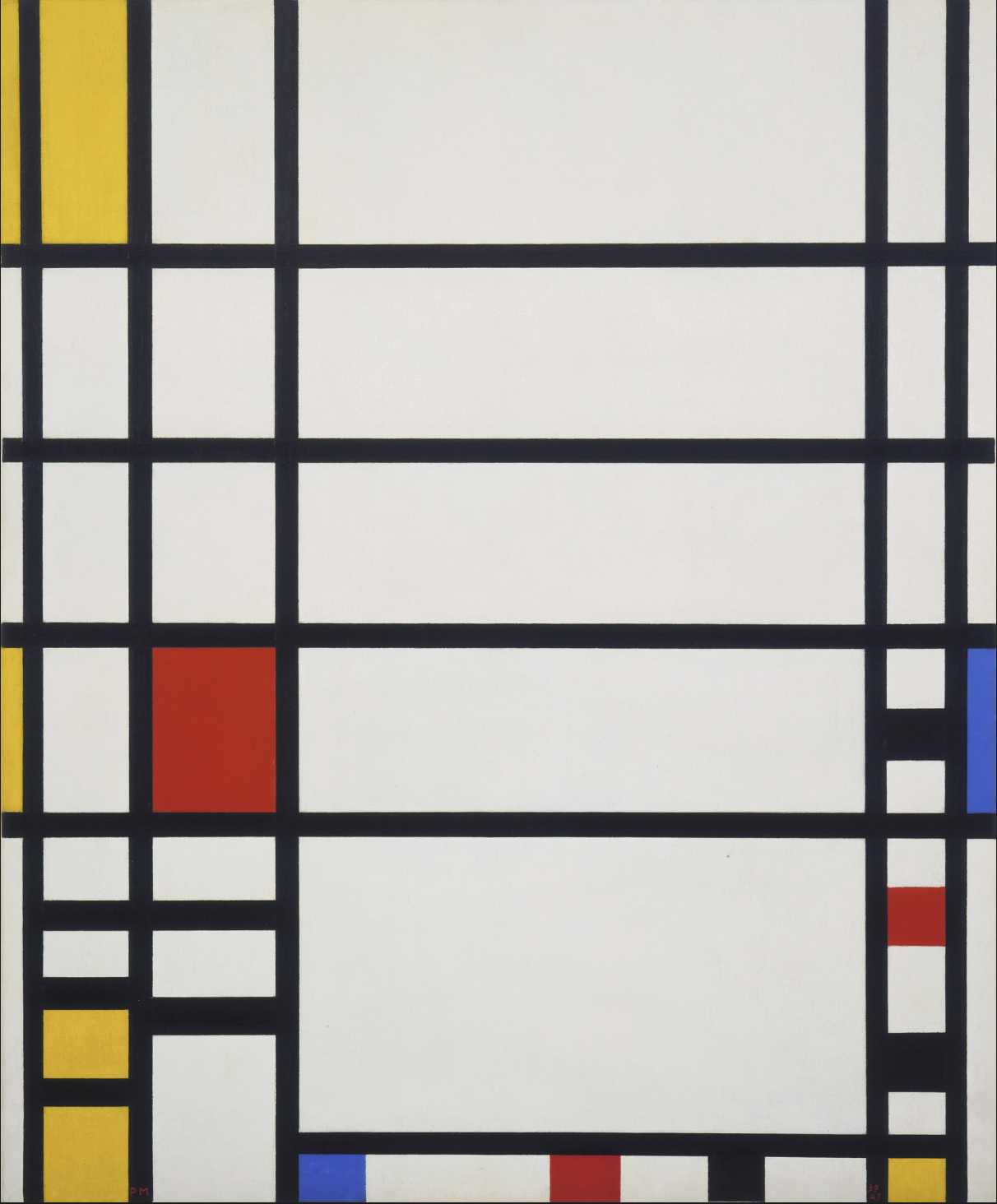

The discussion that evening at Greenberg’s was lively. He surprised the crowd now joining us in his living room by declaring his need to look again at Mondrian, once not being enough. I was startled: I valued repeated viewings, and hadn’t imagined it possible for anyone to feel otherwise. I would come to learn that Greenberg baulked at connoisseurship; though his was a journey of continuous looking and reflection, he prided himself on having no visual memory, meaning that, for him, looking was always looking anew with fresh eyes. Greenberg said he knew he was not alone in having some difficulty with Mondrian, whom he considered an easel painter; painting had moved on. Some art is left behind by the relentless onrushing advancement of history. What seemed more interesting to him – and to me, both then and now, is this: how and why does some art- but not all art -age? Does it get forgotten, or simply mislaid, does it fade from view, slip out of sight?

I kept working to steer the discussion towards Smith. In Smith there might be clues to a way forward: he worked broadly, and his example did much for my early visual understanding of the plane. Here in Greenberg’s apartment, I was looking for enlightened perceptions with which to return to my studio practice. His pursuit of clarity and intensity- in this discussion, at any rate- would not send me searching for the purity which, as he made clear, was for him the final self-justifying discrimination of value. I perseverated over the quality issue; being ‘good’ is not insurance. I knew about myself then, at that point in my development, that my eyes could perceive better than my imagination could render real. It would become a lifetime’s journey, requiring patience, practice, persistence. I shared this with Clem and I have never forgotten his response: ‘You were raised like a man. You are lucky.’ Masculinity, for me, was not a problematic notion, as I had often heard variations of this theme addressed to me; however, luck was a new idea. I was dumbstruck. It would be years before a willed surrender to the apparent irrationality of accepting good fortune would become mine. Luck has big shoes to fill.

My retort to the crowd at Greenberg’s that evening was a reminder that things are more complicated than that; at which all laughed. I would send Greenberg a book, a thank you, the first of many exchanges looking to reclaim, to make a connection to my own purpose. However, I knew then what I know now: making a contribution to the art of your time is in no way a guarantee for what might follow afterwards. Greenberg concluded the discussion with this: ‘The art you may be lucky to make might not have the audience that the quality and addition to art’s continuum warrants if decadence prevails.’

These many years later I still perseverate: for me, Mondrian and Smith are tied together. Neither artist lost to time, both genuinely revolutionary, changing the practices of following generations, their free-ranging experimentation within a framework of workman-like habits professing a shared attitude towards their art. Returning home from the New York City trip that unearthed these memories of Greenberg, I began pulling books down from the shelves, rereading everything I could find there about Mondrian and Smith. Then came the lists, setting out similarities and differences, yet all the while understanding that all the time and data would not resolve everything; the messiness of experience left me knowing more than words allow. Even faith seeks understanding: so much tacit knowledge, like riding a bicycle, needing observation, imitation and practice to come together; knowledge difficult to articulate, to share, or teach. Try explaining love. This is the soup of art making and its appreciation. The drama of interiority is the adventure.

Both Mondrian and Smith live within the ‘Ballerina Syndrome’: making it look so easy. It is not. All working artists look for the cleansing effect of past generations evaporating, infusing their present with an authentic individuality as they move forward. This act of faith given to us by those we admire is that selfsame essence of living we strive to achieve together.

The nature of that first visit to Greenberg’s home is what I have made of these artists’ work: that grit, passion and perseverance with regard to long term, perhaps unobtainable goals, is a calling more than a choice for a life’s work, whatever its reception. After all, one enters the arena to confront one’s ability to grow. The discipline of persistence is not a separate reality. Doing informs influence, part of the discovery in the act of working, triggering an unpremeditated physical response in the studio as the agent of both material and tradition. Even when wrongheaded, this pursuit is the commitment needed in order to approach discovery. If change is art’s consultant, who then keeps up with this pushing of the artist’s metier?

Great collectors are so much rarer than great artists. Art-making is by nature a conservative action, a process of working to attain and maintain the level of one’s past achievements. Making art, of any medium, is a means to test oneself, and through the process test one’s generation against the standards set by the accomplishments of those that preceded it. Collecting is a radical, courageous action. It is a matter of identifying, believing and then supporting, making it possible for the best of culture to grow and thrive. Without the courage of a few the achievements of many would wither. The mirroring of these two pursuits, art-making and collecting, is rising to the challenge of expanding the limits of our artistic models as a matter of the onward movement of freedom. In this, history records how very few great patrons there are.

I am reminded of my first experience of the full impact of this discovery, how artists manage when the market is quiet. It caught me unaware, roaming through the Hirschhorn Museum’s 1978 show ‘The Noble Buyer: John Quinn, Patron of the Avant Garde’. For many historians, John Quinn was America’s first great patron, supporting the Armory Show, as well as many other artists, and bringing the tradition of Europe to New York City. Quinn’s influence is considerable, though for many undetectable. Quinn felt that he was an artist by definition; perhaps he meant the list he made (abstract as it is, like a title of property) was his work, leaving the objects to return to the market at the time of his death.

Legacy for art makers and patrons is an affair of entangled empathy inside a complicated set of relationships. Harry Holtzman, Mondrian’s patron, after giving the artist agency during his lifetime, then managed his estate. Lois Orwell, that strong supporter of David Smith, often brandished that support as her life’s most important achievement: protecting the work, donating her collection to the Fogg, confirming their relationship for the ages. Both Mondrian and Smith benefited from these relationships of patronage; the patron as collaborator, encouraging and challenging invention and expression, so intimate, so timely and so far from popular cultural concerns. Through this transference of creativity, as Picasso needed Braque, as Van Gogh needed his brother, the patron and artist share the way forward. The market version of support is often a dissipation of the creative impulse. Art does not, cannot, exist alone. It is the uncharted, unplanned course we create as we traverse, as we live our odyssey. Vulnerability shared creates opportunity for both patron and maker. As Helen Appleton Read, writing in her Art Center Bulletin review of the ‘John Quinn Memorial Exhibition January 1926′, elaborated: ‘Quinn was in the exact (sense) of the word an art patron, since to patronize anything but the living is not to be a patron, but a collector. His collection is a monument to his belief in the contemporary genius.’

Leaving Greenberg’s place that evening, the inner necessity to move forward located me in the studio, and both these artists, Mondrian and Smith, have accompanied me on the path. It is in studio practice that I have come to recognize the special place both Harry Cooper’s 2001 show ‘Mondrian, The Transatlantic Paintings’ and its accompanying catalogue have in the story of my understanding of influence. Cooper reminds us of ‘the importance of a continuous evolution in his (Mondrian’s) art- of self conscious, self-critical production, constantly generating new form out of itself, of a thrifty recycling and reclamation of every earlier impulse into the New.’ This carefully researched catalogue offers artists the means by which to move away from Impressionism and its plein air aesthetic, measured in lumens: it posits reworking as a form of rebirth; as reconsidered choices, perhaps newly found choices. Mondrian’s habit of dating, or rather double-dating, signifying date begun/date completed, is, as Cooper explained, salient to this endeavour. Here Mondrian (like Smith) had faith in the wholeness of his oeuvre. I too resist definitive dating with work that has found its finish years later. It’s the last mark, which is also in a sense the first or only mark, that completes the effort.

In his essay, ‘Greenberg’s Connoisseurship in Mondrian’s Space’ 1Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art, 2019, Marek Wieczorek reminds us that the black lines of Mondrian’s late work, and the planes the artist claimed he was creating, were changes made that suggest what might yet change between them, in which rhythm as well as balance is created. The studio walls on which Mondrian painted and hung coloured placards were the trial run for his paintings’ internal layout. Mondrian knew what to leave out.

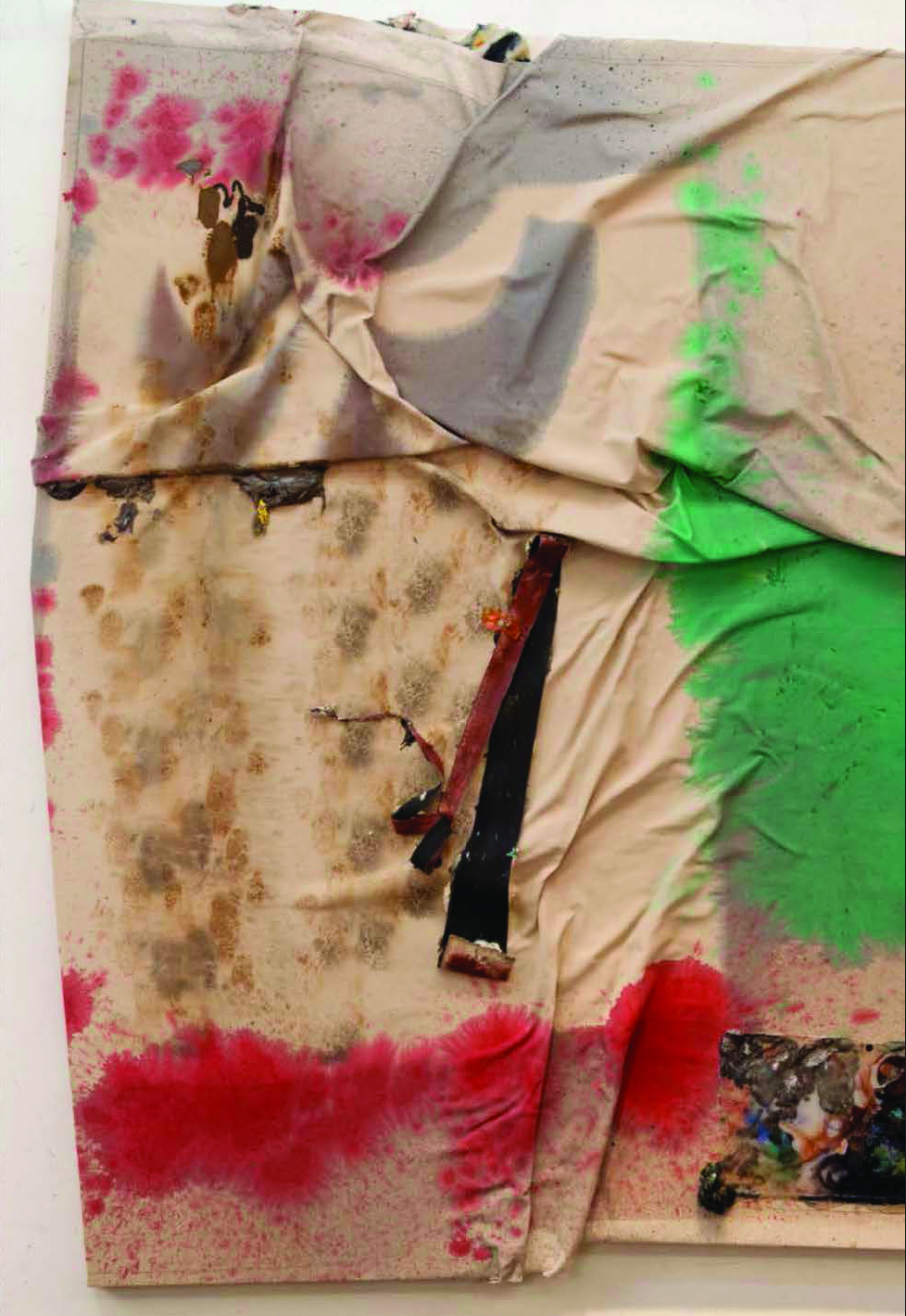

Wieczorek refreshes my understanding that Greenberg’s description of Mondrian’s line as his third colour imagines it as a rectilinear lasso, rather than a set of boundaries around the ‘islands’ of his paintings. Perhaps, in my art, I might grow, spread that black, make a plane and capture those islands (not empty centers, rather silent ones), beyond my understanding. Returned from New York, I took this insight into my studio making daydreams my canvas’s reality, finding a door to my past open to new work. I began on black canvas, a black portraiture linen substitute, and laid out squares, prompted by the challenge set before me by Ken Noland on my last visit to him. I am proceeding in this direction still.

David Smith left a lot of shade; unsurprising, given the expanse of his oeuvre. My first sustained experience of Smith was his 1969 exhibition at the Guggenheim, where I felt his redefining of both sculpture and painting. Being seated so close to Smith’s sculpture at Greenberg’s place all those years ago was extraordinary: I could, and did, reach out and touch the work! Here the cathartic, revitalized sensation I felt, witnessing the making whole of a democracy of disparate parts, completing a coherence of perhaps incompatible elements, was overwhelming. Though I never saw the fields at Bolton Landing filled with Smith’s sculptures, as pictured in Dan Budnik’s photographs, I can say that David Smith is as big as all outdoors indoors!

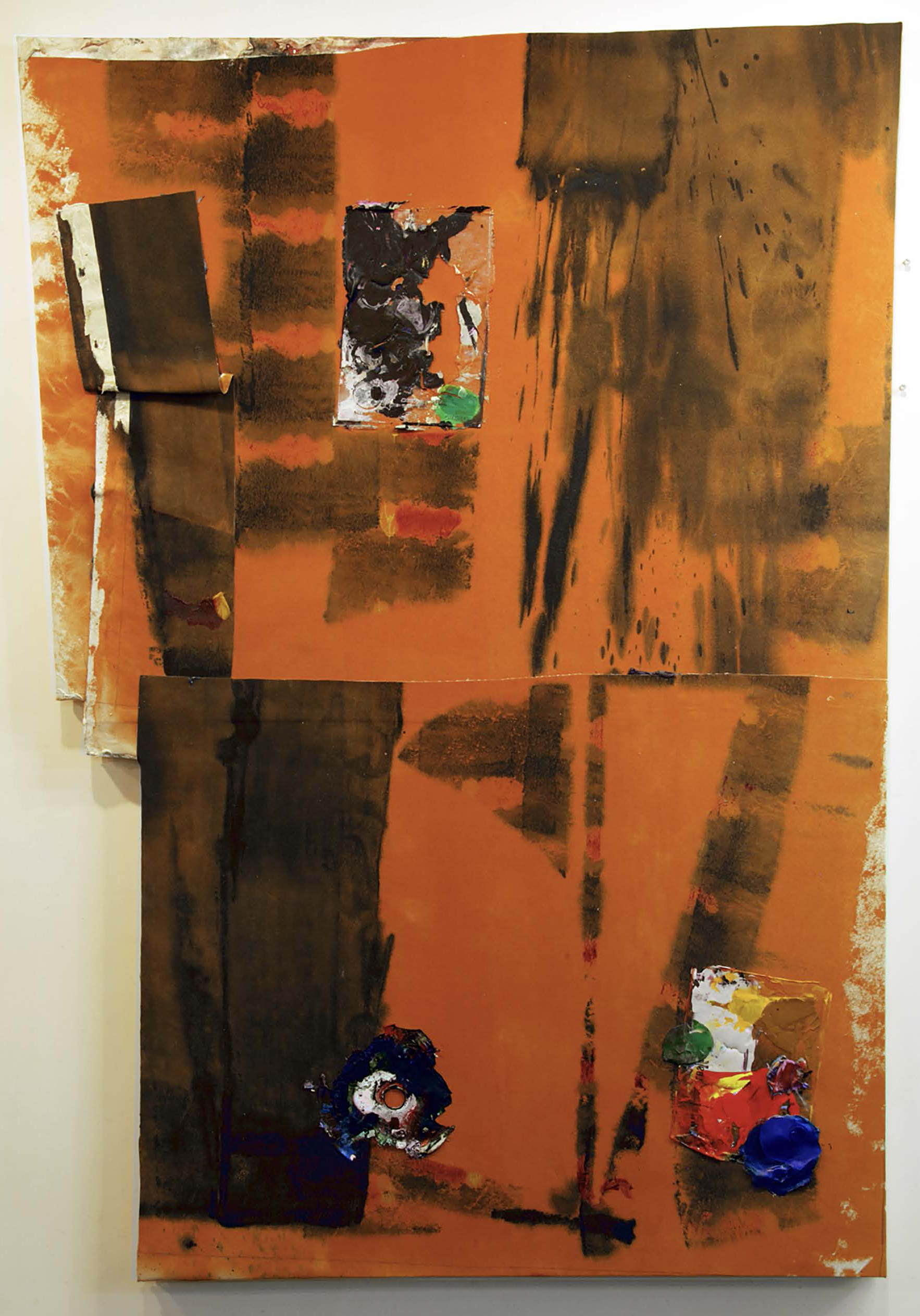

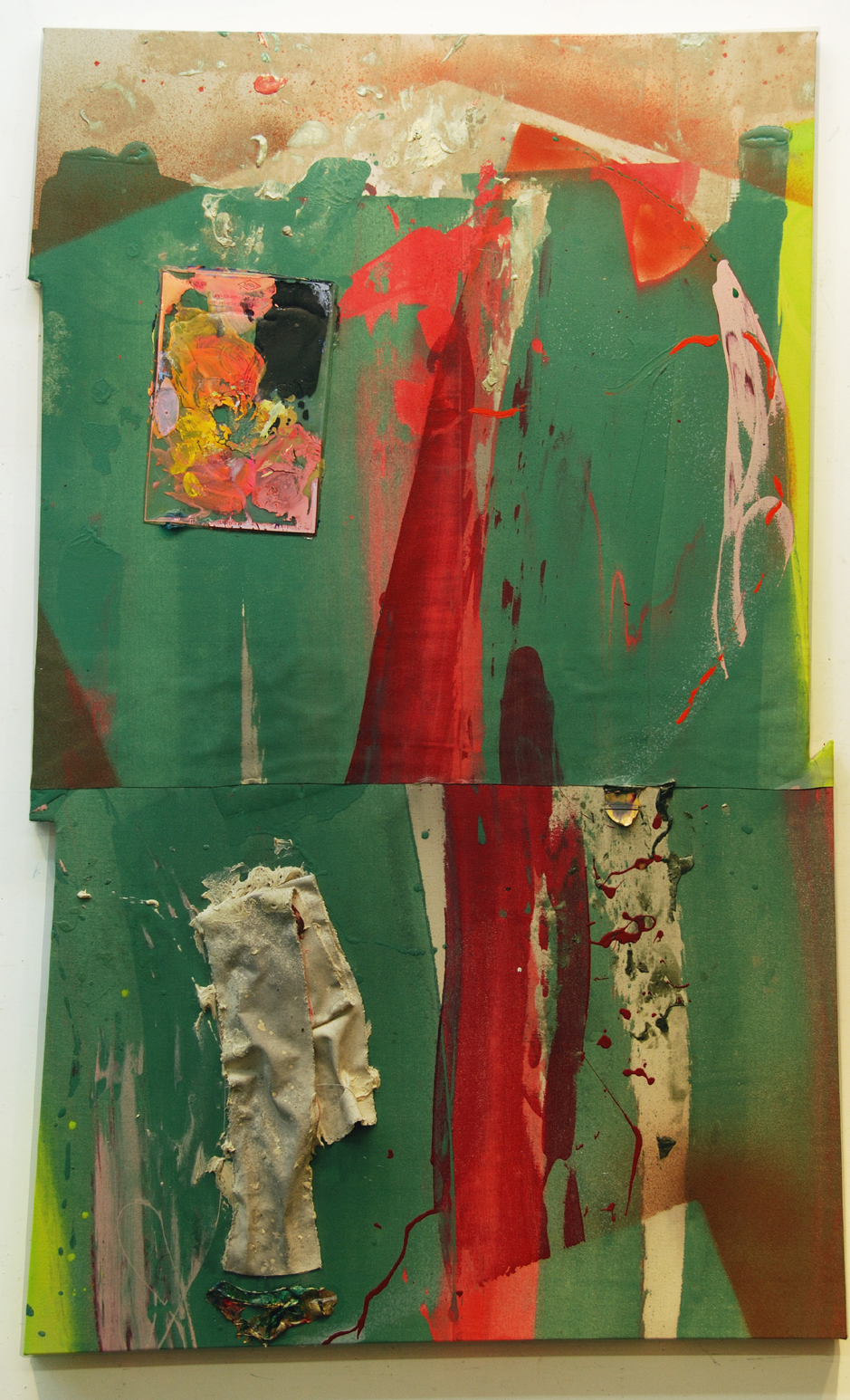

Countless readings of ‘David Smith by David Smith’ have shown him as having an attitude so necessary for an explorer; he had both the backbone and temperament for the job. Karen Wilkin’s sustained viewing and writing about Smith expresses the essential characteristic of his legacy: ‘Smith was obviously of his time but not confined by it.’ How much that matters now: the uplift that genius brings. Accepting every part of his own oeuvre, Smith affirmed the instinct to experimentation. Smith’s painting and use of stencils, his preparedness to take all procedures seriously, for example, ghost-like images, the marks left on the studio floor after arranging and painting steel components for his sculpture inspired his painting. This brings to mind collage’s lesson: the elements are pieces of time that get shifted and layered, added and subtracted, with the lapsed time always leaving the trace of its passage. Like Max Ernst before him, Smith came to understand that collage is an attitude, not a technical procedure. I have licence, courtesy of David Smith.

Back at Greenberg’s place, many years after that first visit, Clem, knowing I was going to Italy for the first time, handed me a Berenson book from his shelf. ‘Here, he said, take this. Berenson is not always right, but if you disagree with him, go back and look again.’ I took the book and shared a Nabokov quote with him: ‘A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a re-reader.’ I can still see him nodding his head in agreement.

Keep looking and look again.

‘To be different: this is the rule the precursor imposes.’

José Luis Borges