‘The Mirror at Night’ at Cross Lane Projects: Exhibition review by Patrick Bryson; Interview with Curator Peter Suchin

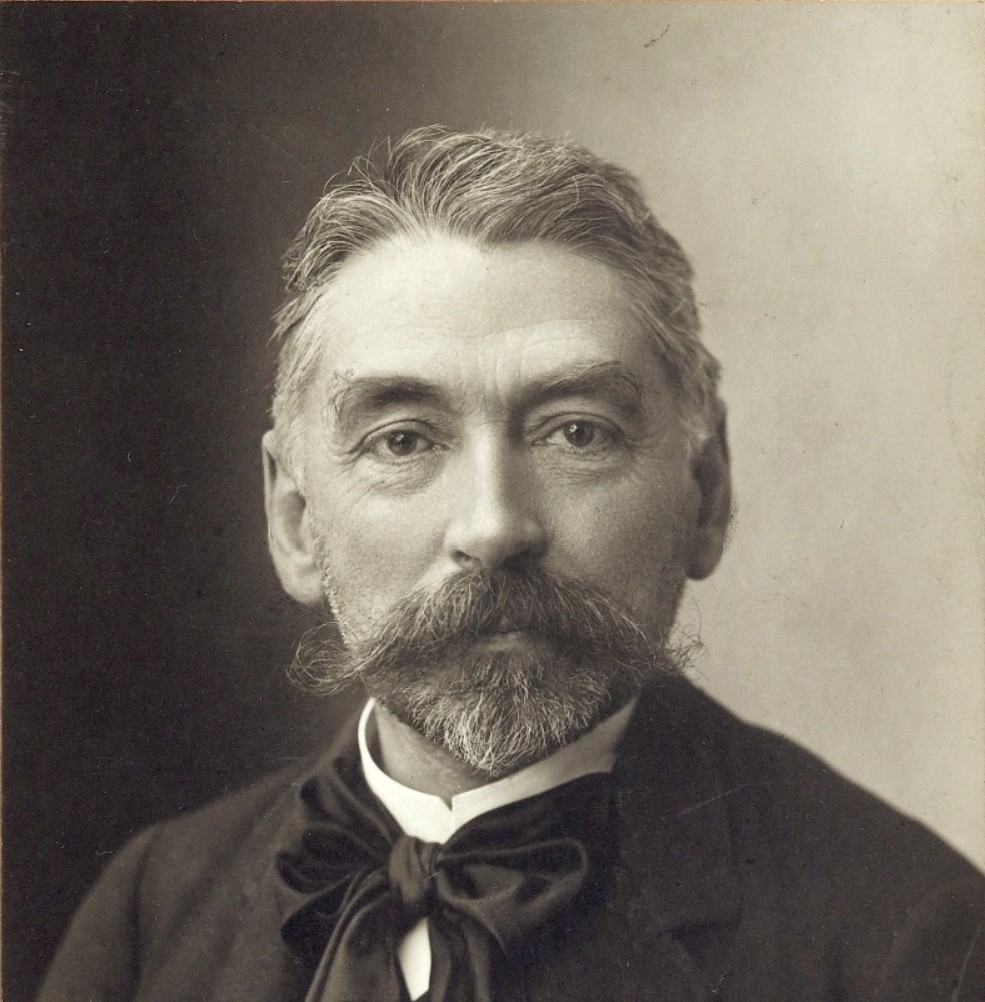

The exhibition The Mirror at Night at Cross Lane Projects, London, curated by Peter Suchin, is centred on a poetic fragment by Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898), using it as an anchor and launch point for the show. Mallarmé’s work is striking in its commitment to ambiguity. He did not write merely to confuse, but to affirm ambiguity as a vital, creative force.

Mallarmé’s poetry is not obscure for its own sake. Rather, its ambiguity functions as a strategy to resist rational discourse and to invoke an openness to experience. He saw language not merely as a descriptive tool, but as a medium of mystery and suggestion.

His work stands in response to the scientific, rational materialism of the 19th century. Where those forces offered clarity and certainty, Mallarmé declared resistance. His poems test straightforward interpretations, inviting an active, participatory engagement with meaning. This refusal to be fixed was both a philosophical stance and an aesthetic breakthrough.

In this spirit, the works in The Mirror at Night span painting, sculpture, and installation, each carrying their own internal logic, yet examined through the exploration of ambiguity. Suchin’s curatorial framing offers a valuable guide to navigate the show’s complexities.

Ambiguity is not merely a hallmark of modern art; it is one of its central tensions – between coherence and dispersion, presence and absence, meaning and meaninglessness. The viewer is invited to consider whether, in each work, ambiguity is a gateway to something deeper or a screen against clarity.

Take ‘Seven Meet’ by Louise Bristow. Referencing the number seven, symbolically significant in Mallarmé’s cosmology, the piece is rendered in a realistic style. Fragments of disparate scenes are collaged into a theatrical backdrop, anchored by a central image of the cosmos and surrounded by cubistic forms and art-historical references. None of the depicted elements are ambiguous in themselves, but their juxtaposition resists resolution. Ambiguity here does not arise from vagueness, but from the unsettling interaction of recognisable parts.

Keith Bowler’s ‘Floating Sculpture’, a tabletop version of a full-scale 1984 piece, comprises six buckets of water, each with a floating cork at its centre, held together by a precise framework of wooden dowels. The geometry is clear, the materials unambiguous. Yet the sculpture’s meaning remains suspended. It floats within the wider ambiguity of the exhibition, a meditation on the physics of structure without interpretation.

Susie Hamilton’s ‘Red Dining Room’, an oil painting depicting a social scene, shimmers with painterly suggestion. Figures sit at tables bathed in evening light, rendered loosely and impressionistically. It evokes warmth, conviviality, perhaps memory, but what are we really seeing? The forms are familiar, but undefined. The viewer is asked to consider: what does it mean to ‘see’ a dining room when its features are only hinted at? How does suggestion shape perception?

These are just three of the many works in what is an eclectic, at times overwhelming, display. Yet Suchin’s thematic framework gives the viewer a conceptual compass. Ambiguity becomes the thread by which to engage with the show.

On leaving the exhibition, one might begin to reflect more broadly: what role does ambiguity play in meaning itself? Is there cohesion, relevance and thus, significance?

J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) is renowned for his painterly ‘indistinctness’, which was not vagueness but revelation. His abandonment of detail opened a space for atmosphere, light, and the dissolution of the self into nature. For Turner, indistinctness revealed a spiritual reverence for natural forces.

Mallarmé, who overlapped Turner in time, was working in a different medium but shared this impulse. Disturbed by the cultural drift toward rationalism, he sought to confront its limitations through radical ambiguity (indistinctness) and linguistic fragmentation. Not to obscure, but to point toward mystery, multiplicity, and the perpetual deferral of final meaning.

Such artists endure because their work was a passionate and essential encounter with meaning.

By contrast, much contemporary ambiguity emerges from a different historical ground: postmodern fragmentation, irony, and a suspicion of grand narratives. In this context, ambiguity often signals resistance to closure, an openness to interpretation, or a refusal of institutional authority. At its strongest, it invites complexity. But at its weakest, it becomes a gesture of avoidance, an evasion of commitment masquerading as intellectual freedom. What presents itself as sophistication may, in truth, be an ironic retreat into meaninglessness.

The infinite overwhelms not through obscurity, but through scale, intensity, and presence. Ambiguity can open the door to creative, infinite possibility, but only if it points beyond itself. When it arises from the limits of language in the face of something vast and unknown, it retains power. When it becomes an end in itself, it risks collapsing into aesthetic nihilism.

So the question arises, as we move through each work in the exhibition: is ambiguity here a gateway to deeper understanding, or a shield against it?

Suchin deserves credit for surfacing this question. ‘The Mirror at Night’ offers more than a collection of objects, it becomes a contemplation on meaning itself. In an era where exhibitions too often feel like disconnected sequences on white walls, this show asks us to pause.

In such settings, meaning is often neither proposed or confronted, but sidelined, leaving the artworks and the viewer suspended in a fog of disengagement, wondering what they are looking at and why.

The real question is not whether meaning still exists, but whether we are willing to believe it matters enough to pursue.

Peter Suchin in discussion with The Coincidence Gallery regarding The Mirror at Night

The Coincidence Gallery: You have chosen a text to frame the show; is that to create context that will help to generate a conversation around the theme?

Peter Suchin: I wouldn’t say it’s framing the show as such. I think it’s a theme being used in the literature already. It’s more of a trigger – this isn’t a technical term, as it just means a starting point – a pivot perhaps, something to generate the exhibition.

TCG: So, can you tell us why you chose Stephane Mallarme’s sonnet ‘Ses purs ongles tres haut dediant leur onyx’ of 1887?

PS: I’ve been reading Mallarmé on and off for many years. What interests me is the openness and ambiguity in his work. When reading scholarly writing about his work I noticed this particular text is often cited as one of his most self-contained poems. It’s also seen as one of the most difficult. And by ‘difficult’, I think critics mean that no one really knows what it means. There are references and allusions, but there’s no fixed reading. You couldn’t simply say to a group of readers, ‘this poem is about X, Y and Z’, as you might with another writer. Mallarmé resists that kind of closure.

TCG: So apart from your personal interest, why Mallarmé now? I mean, given where we are in the history of art, does he have some kind of renewed significance?

PS: Absolutely. Think of Roland Barthes and his famous essay ‘The Death of the Author’. Barthes writes about polysemy, the idea that a text can support multiple, contradictory interpretations. In that view, the reader is regarded as a creator of meaning whose contribution is at least as important of that of the author’s; he or she is not seen as merely just a supposedly passive receiver of, to use Barthes’ expression, the ‘Author-God’.Barthes actually cites Mallarmé as a precursor to this idea. Mallarmé, as a modernist, in effect anticipates a lot of postmodern thinking about authorship and the role of the reader—he was doing this around 150 years ago. His work isvery relevant in the context of contemporary art, in which the idea that the viewer’s engagement completes the work has become an acceptable aspect of their engagement with it.

TCG: So, Mallarmé could be seen as a precursor to this whole shift, from the authority of the Author to the responsibility of the Reader or Viewer?

PS: Exactly. I’ve grown tired of exhibitions where there’s no complexity—no real conversation, just a very vague theme and a title, and then artists throw something in that they think will suffice. Sometimes with current shows there is hardly even a list of contributors. It becomes meaningless, an easy way for someone to claim they are ‘curating’ something. So, I wanted to invert that, to invite artists into a space of complexity, of ambiguity—not just let that be a background condition, where almost ‘anything goes’, but an explicit framework that the artists can actively explore.

TCG: A recipe, or conditions for conversation and inquiry? Are you calling for shows with context, for dialogue, something for artists and viewer to focus on, and to work with?

Peter: Yes, though I don’t think ‘recipe’ is the right word. In this particular case, if you value ambiguity, you’re going to get different responses anyway. But I wanted to make it more specific. So, I introduced Mallarmé and in effect said, ‘Here’s this figure, here are these ideas. Look through his work rather than just approach art as ‘anything can be anything.’’ That attitude where one vague word or ‘theme’ can be the apparent reason for a whole show, and it’s maybe the same eight or ten people who turn up in these rather limited – and limiting – exhibitions: one is referring to a certain east London context here, a quite narrow network of exchanges. There is a certain ideology of a return to ‘proper’ painting that has become a cliché. It’s lazy curating and lazy brief-writing. There’s no challenge to the artist. I wanted to complicate things, not water them down; I wanted to propose the notion of an intelligent response to a set of ideas. It certainly isn’t about illustrating the brief or the material presented. I think some artists misunderstood this and thought they had to illustrate or depict the poem, pick one of the seven translations of the section of the work I had singled out (the last three lines of the sonnet), and make something directly alluding to a specific English rendition of the French. But the project isn’t about representation—it’s concerned with process, active engagement. The artists aren’t being asked to represent Mallarmé, it is more a case of responding via a kind of lens or approach to what is already a complicated object, which has been made even more complicated through the provision of seven different English translations of the selected passage. The implication is that the poem is made more ambivalent in its ‘meanings’, not pinned down in a neat English transcription of some very elusive French.

TCG: You’ve included seven translations of the same three lines of the poem?

PS: Yes, and this multiplicity of reference is itself part of the brief. The translations differ, sometimes considerably, though they are all English, and that adds another layer of ambiguity. One could say, ‘I can’t read French, I need a translation.’ But none of the translations is definitive. They open out the poem further, rather than reduce it to a clear statement. Mallarmé’s emphatic ambivalence, his unorthodox punctuation and invention of new words (for exampleptyx in the second stanza) carry over into the translations. One aspect of the project is the issue of translation itself: can this poem be ‘correctly’ translated anyway? Walter Benjamin’s famous 1923 essay on ‘The Task of the Translator’ is relevant here.

Each translation of Mallarme opens a slightly different reading. Some are more lyrical, some more literal than others, but there’s no perfect or ‘true’ version, and that’s important. The translations themselves become part of the artwork—like a mirror that reflects things slightly differently each time one looks into it.

TCG: Seven. And how did the number seven become a structuring element?

PS: The number seven appears in Mallarmé’s work in symbolic ways, and some scholars believe it refers to a ‘secret number’ alluded to in his poem ‘Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hazard’ of 1897 – see the book by Quentin Meillassoux. Initially, there were going to be seven artists in the exhibition; then it went up to fourteen, then twenty-one. It gave me a kind of structuring principle. I’d done a show in entitled Seven Turns, which also in part explored that number in 2016.

TCG: And why the final three lines of the poem specifically?

PS: Initially the show had a much broader theme, just ‘mirrors’, but that felt far too vague because anything can be a mirror. These three lines refer to a room containing, in the main, a mirror – there’s a beautiful duality: the intimacy of an interior space, and the vastness of the heavens, as reflected in the mirror through the open window of the apartment is a constellation consisting of seven stars. Mallarmé condenses – he at least implies – a huge amount (in several senses) into only a few words. I didn’t want to ‘overwhelm’ the artists with the full poem—it’s very dense. So, I chose something focused but still open-ended.

TCG: What sort of work has emerged in response to the brief?

PS: Quite a mix. Some artists spent a long time researching Mallarmé, while others engaged more loosely, exploring ideas of reflection, translation, or fragmentation. A few people didn’t really attend to the brief at all, but submitted already-existing work. That wasn’t ideal, but I also didn’t want to be too prescriptive.

TCG: So, you allowed some flexibility in how artists engaged with the brief?

PS: Yes, but I wanted to avoid the kind of open-endedness I refer to above, where ‘anything goes’ and nothing really matters. That kind of curating—where the brief is just a single word and there’s no broader framework—is, in my view, quite sloppy. Ambiguity is fine, but it has to be held, not just floated. The show has to give something to the viewer beyond a surface gesture.

TCG: Speaking of viewers—what are you hoping for when someone walks into the gallery?

PS: I want them to be engaged, maybe even provoked. I’m not expecting them to go home and read Mallarmé. But I do want them to realise that art can – and should – invite thought, not just visual consumption. So much of the art world today seems to want to separate the intellectual from the visual. As if thinking undermines the ‘magic’ of making. But why shouldn’t artists be intellectually curious? Why shouldn’t they read, research, think? And the same goes for the audience too.

TCG: So, you’re not calling for strictly intellectualism, rather depth-discernment?

PS: Exactly. Complexity isn’t elitist. It’s enriching. And art can reflect and participate in that. We’re not just monkeys moving paint around a on canvas. There’s more at stake.

TCG: Regarding the visitor: if someone came to the show and found themselves caught up in questions – about language, perception, translation, even self-reflection—you’d call that a success?

PS: Definitely. That’s the kind of viewer I hope for, someone willing to engage with ambiguity rather than run from it; someone who might even walk away with more questions than answers.

TCG: Thank you, Peter.

‘The Mirror at Night’ was at Cross Lane Projects, 6 – 8 Vestry Street, London, N1 7RE. 26 April – 7 June, 2025, curated by Peter Suchin. Artists included: Tabatha Andrews, Keith Bowler, Louise Bristow, Maria Chevska, Gary Dennis, Nooshin Farhid, Lucy Gunning, Susie Hamilton, Lee Holden, Lizzie Hughes, Deeqa Ismail, Lucy Jagger, Simon Leahy-Clark Fabian Peake, Jon Ridge, Giorgio Sadotti, Christine Stark, Peter Suchin, Chris Tosic, Steven Wong, Mark Woods.