Alan Gouk, Charley Peters, Matt Dennis: Fifty Years of ‘Painters Painting’

It’s now fifty years since the release of Emile de Antonio’s documentary, ‘Painters Painting’.

Despite his being on friendly terms with nearly all the artists featured in it, nothing in de Antonio’s track record as a filmmaker had led anyone to anticipate the arrival of this deep cinematic delve into the American avant-garde. He had made his name in the 1960s with a body of documentary film work that was ‘unashamedly oppositional…and stubbornly class conscious’,1Ed Halter, 4columns.org dealing with- amongst other radical causes celèbres– the McCarthy hearings, the Vietnam War, and the Nixon Presidency. As de Antonio himself acknowledged, his colleagues on the American left expressed shock and dismay at his decision to point his camera away from political subject-matter, and train it instead on a clique of New York abstract painters making what were widely seen- in radical circles, at any rate- as nothing more than brightly-coloured baubles to decorate Rockefeller-funded museum walls, and the homes of the super-rich. Nevertheless, ‘Painters Painting’ catapulted its Director from cult status to widespread fame, and installed itself within the culture, both in the canon of epoch-defining art documents, and on the art-history syllabus of two generations’ worth of painting students.

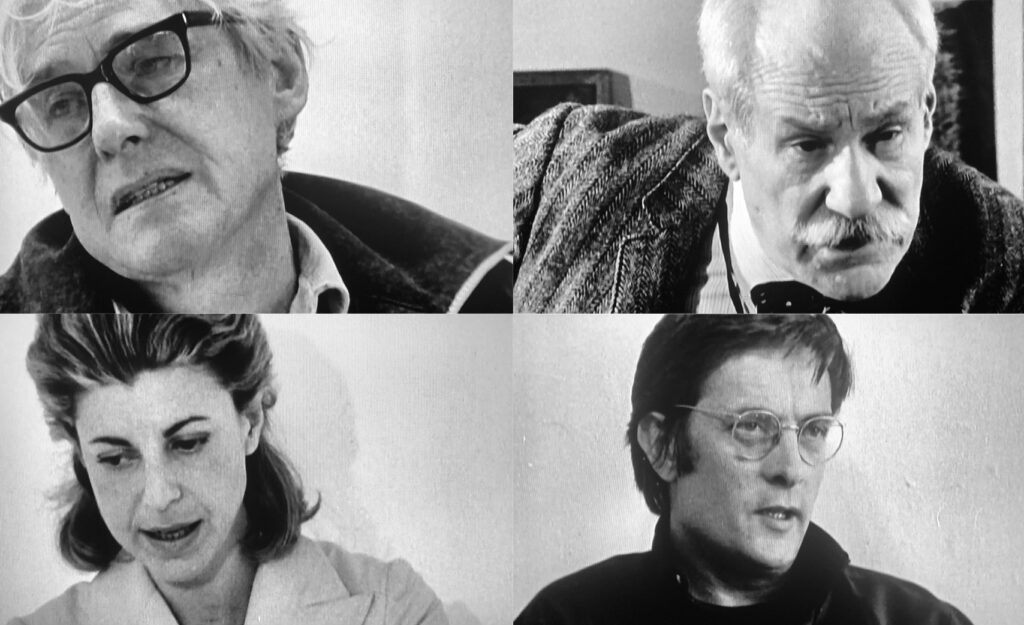

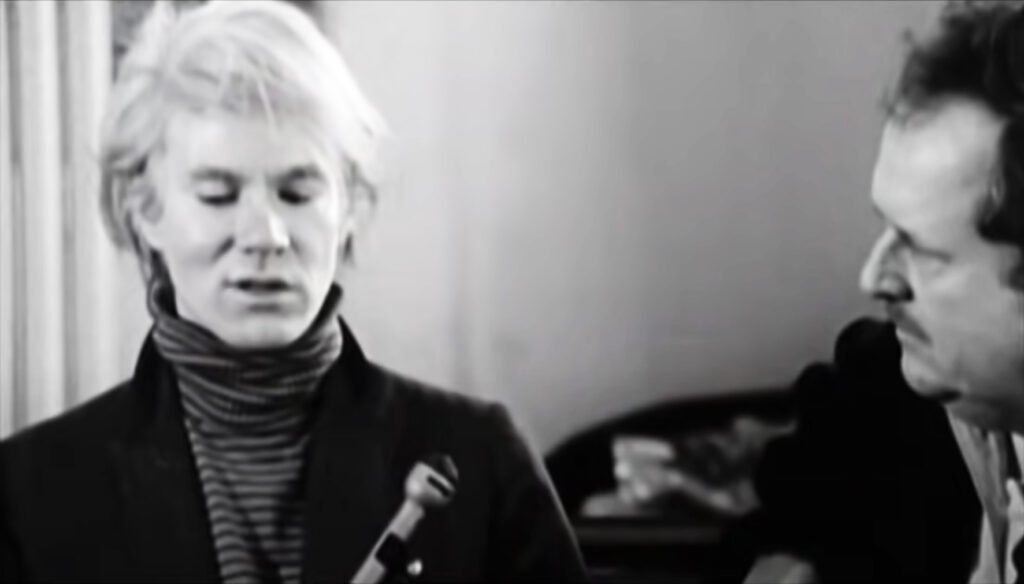

Part homage, part historical record, part critique, part exposé, ‘Painters Painting’ probes and prods at the artists and the art, coaxing from the mixed roster of Colourfield painters, Pop artists and still-surviving first-generation Ab-Exers (plus critical voices from both team ‘yes’ and team ‘no’) a whole gamut of responses, from the foghorn oratory of Barnett Newman, to the calm explanatory delivery of Helen Frankenthaler, to the tetchiness of Larry Poons, to the affectlessness of Andy Warhol. Echoing the patchwork quality of its content, the film’s look and sound undergo frequent, sudden shifts of register, cutting between silent colour sequences in which the camera glides through museum galleries, lingering over mural-sized abstractions, and interviews conducted mostly in black-and-white in echoey work spaces with the lone voice of the artist filling the silence, or fighting to be heard above the ambient roar of a radio tuned to a rock station, punctuated by off-camera hammering, sawing, drilling; all the daily business of studio art-production in Manhattan at the end of a pivotal decade for abstract painting. Somehow, out of the din of this two-hour sensory assault, out of all the competing voices, a narrative seems to form itself: of where this art has come from, and where it might be going.

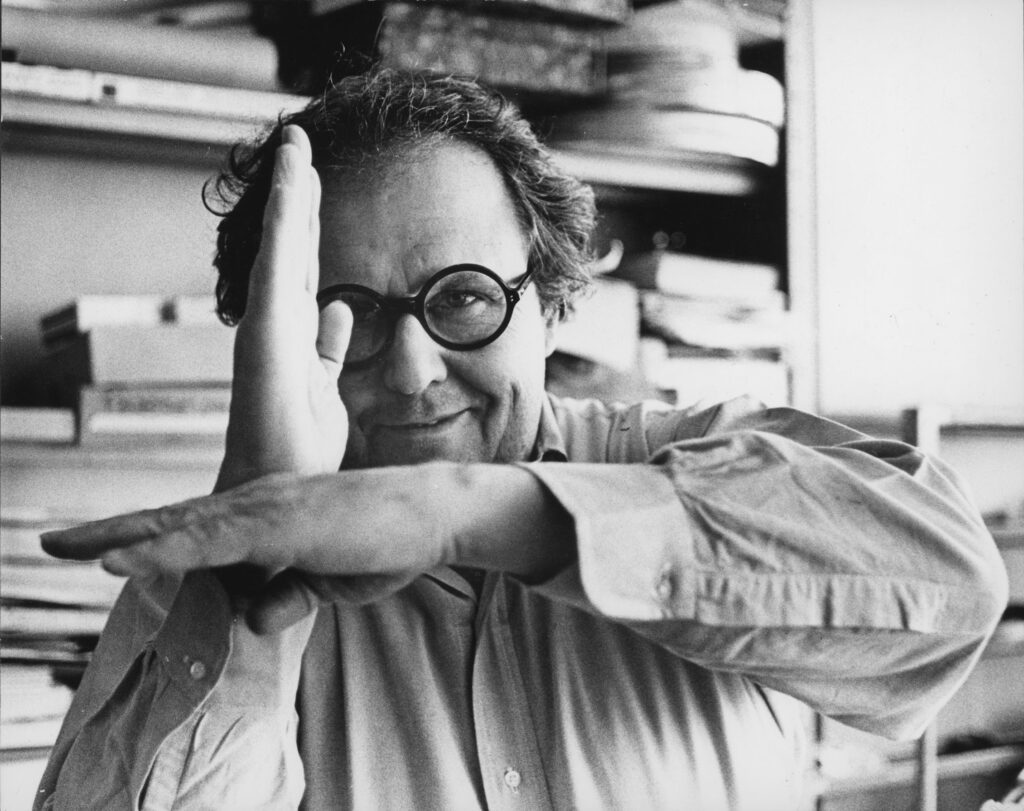

To mark this half-century milestone, and to pay its respects to a film that, for all its blind spots, omissions and oversights (discussed in depth in the texts that follow this introduction) has nevertheless earned its near-mythical status by virtue of its breadth, its depth, its dynamism, and its preparedness to take its subject seriously, Instantloveland has put together a two-part feature: the first part being an essay by painter Alan Gouk, who knew many of the protagonists in ‘Painters Painting’, and spent time visiting with them in New York around the time of its release; his ‘Notes on “Painters Painting”’ offers a painter’s perceptions of the time and the milieu in which the film was shot, and of the arguments put forward in it, most notably those of Clement Greenberg. The second part is a dialogue between painter Charley Peters and Instantloveland’s Matt Dennis, in which they offer a close reading of the film: hoping- by asking what exactly de Antonio intended ‘Painters Painting’ to achieve, and whether it achieved it- to shed fresh light on an exasperating, meandering, yet sporadically brilliant piece of documentary film-making, and on the moment in American art that it fixed forever on celluloid.

‘Painters Painting’ can be watched here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SrM39J6GLvU

Alan Gouk’s recent paintings are being shown here: https://www.hampstead-school-of-art.org/news/hsoa-gallery-alan-gouk-new-paintings-2019-2021

Alan Gouk: Notes on ‘Painters Painting’

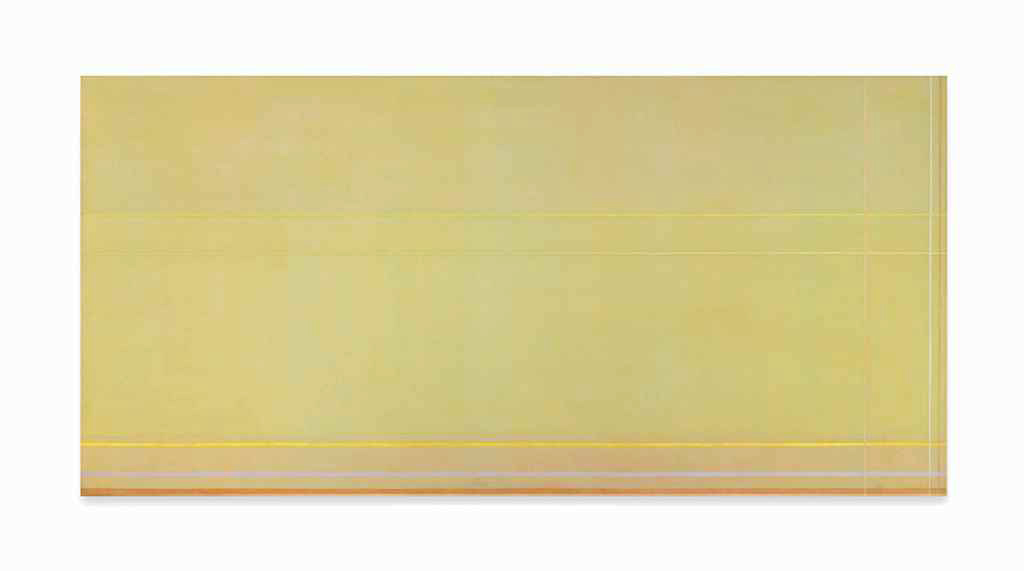

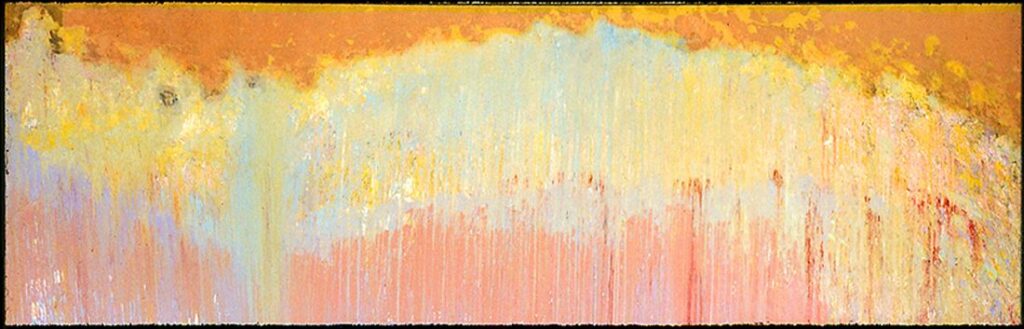

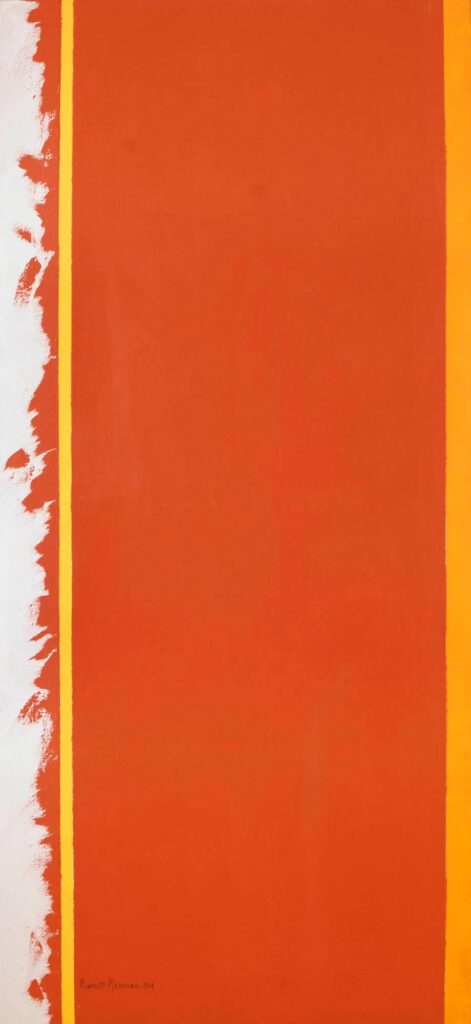

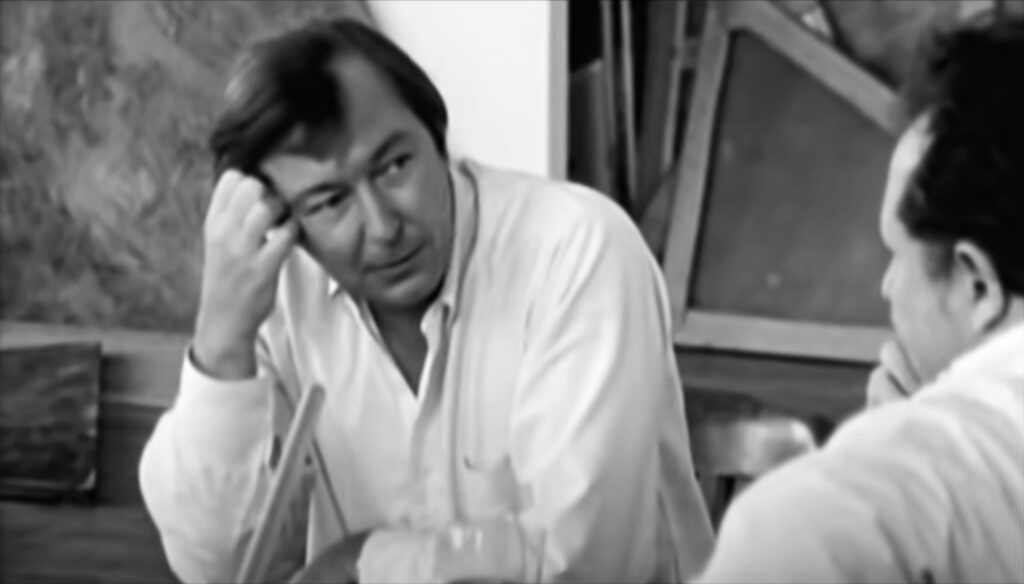

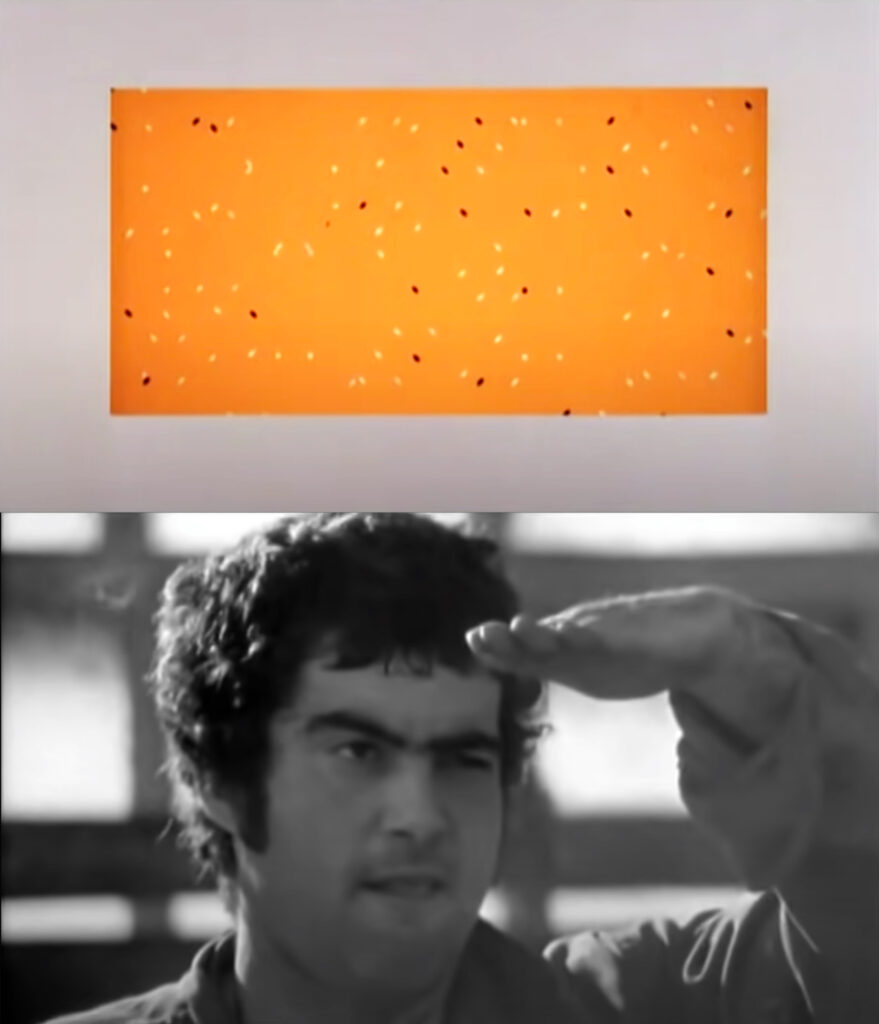

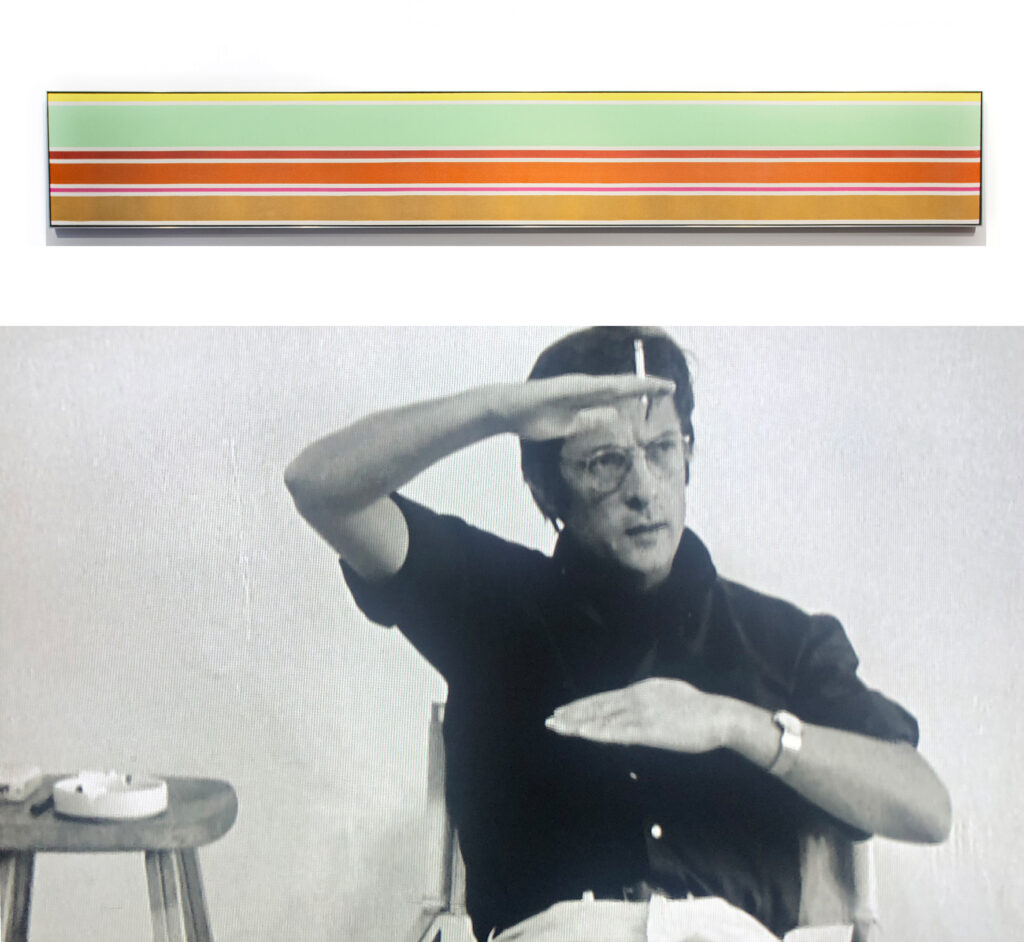

I spent a few days in Kenneth Noland’s Bowery Studio in April 1972, not long after de Antonio had filmed him for inclusion in ‘Painters Painting’, in front of ‘Sun Bouquet’ of 1971, a longish horizontal picture which I saw later in a group show of painters, all American, all living, and mostly colourfield, curated by Kenworth Moffett at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Noland was then working on a variant of ‘Sun Bouquet’, with thin, overlapping, edge-hugging bands of pale, high-keyed colour around both vertical and horizontal axes, a development that would lead to the ‘Plaids’– a series of shaped canvases, mostly diamonds, in which narrow bands overlapped one another both horizontally and vertically, as in a tartan, reminiscent of some late paintings by Mondrian.

Noland had begun to experiment with gels and other additives to vary the lustre of the bands, sometimes embedding them in a thicker layer of gel which was applied to the surrounding expanses. He was worried that they might be perceived as too influenced by Olitski, who was in the ascendant, usurping him in the pantheon of Greenberg’s favourites,2 As chronicled in Florence Rubenfeld’s ‘Clement Greenberg: A Life’ (2004) and who was becoming the major influence on a younger generation of colourfield painters.

There was one such painting of Noland’s in the Boston Show, belonging to Michael Fried, who had fallen out with Greenberg over some disagreements or contradictions he, Fried, had voiced. At the opening, wafting through the rooms with an entourage that included Darryl and Margie Hughto, Michael Steiner’s girlfriend and others, Greenberg pointed to Fried’s picture and said – ‘That’s a bad Noland’.

De Antonio was clearly enamoured of the New York art scene, as presided over by arch-manipulator Leo Castelli. Perhaps he would have been less so, if he had known what certain participants in that scene thought of art being made elsewhere. I watched embarrassed as Noland and his sidekick Peter Bradley humiliated two young French critics who had called on him to pay homage — the Americans sneering at both the Ecole de Paris’s decline into fussy mannerisms, and at the chic Faubourg St. Honoré version of Pop Art, such as Martial Raysse. No matter that they were right: it was all so unnecessary, so ill-mannered and so cruel; New York chauvinism at its finest. And so defensive with it, given that their own prominence was coming under increasing threat from all sides.

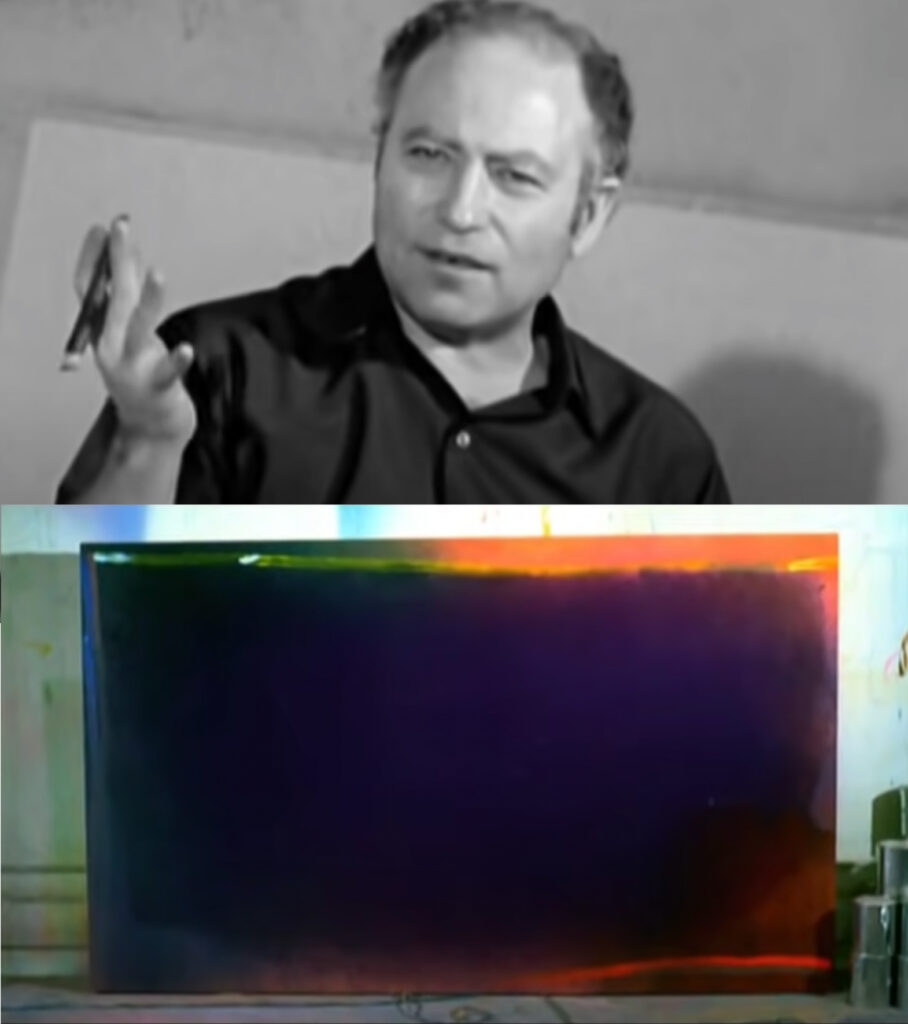

I also visited Olitski’s (formerly De Kooning’s) studio above the Pratt Institute in Lower Broadway, in the company of John and Jan McLean, and David Evison. Paul Jenkins had the studio above. Olitski, then aged 50, was just recovering from a bout of pneumonia brought on by overwork. The paintings were laid out on the floor ready to be cropped, right up to the edge of his bed, which was spattered with sprayed paint. He was rather subdued and tired from the illness, but had a certain gravitas which no doubt contributed to his cult status at that time. He was rumoured to be writing a roman à clef, to the alarm of those who knew about this, and feared that they might be in it; but to the best of my knowledge it never materialised.

Olitski had a painting by Hofmann hanging prominently — ‘Ave Maria’, which had been brilliantly described by Walter Darby Bannard in his seminal Artforum essay, ‘Hofmann’s Rectangles’,3http://wdbannard.org/1969-Hofmanns-Rectangles-10.htmlwhich I have quoted from in the past.

In ‘Painters Painting’, Olitski is holding a small fluffy dog4For some reason I remembered it as a cat like a Bond villain, as he describes his working practices. ‘What would happen?’ he says; ‘What would happen if I flooded a load of glop over the picture?’ And of course, for a while everyone did just that; Darby Bannard continued the practice well into the 1990s.5This was twenty years before Gerhard Richter, the Saviour of Painting, did so. In 1972 Richter was palling around with Warhol at the Factory

We also went to a party at Larry Poons’ loft studio below Canal St and traipsed up the wooden staircase past walls caked in dripped paint runs, up to his mezzanine living area. We were all dancing, bouncing up and down to his favourite flamenco guitar records (from his days as a music student), and Poons was tearing his hair out as the needle jumped on his beloved shellac discs; this from the hell-raising, druggy motorbiker of legend.

In the film, Poons can be seen struggling to release a large canvas stuck to the floor as a result of his then practice of pouring paint centrally and allowing it to puddle out to the edges. A rare survivor of this period, ‘Polish Mix’ of 1970/71, one of the set of paintings dubbed the ‘Elephant Skin’ pictures (by Fried, perhaps?) is in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Any and all others appear to have been excised from the record.

How Poons got from there to ‘Railroad Horse’s thrown and dripping curtains of running paint in late 1971, I have detailed elsewhere and won’t repeat here. Kenworth Moffett claimed that Poons’ change of style was attributable to a visit from Greenberg, and bought ‘Railroad Horse’ for the MFA, Boston, while the paint was still barely dry.

We also visited Helen Frankenthaler, but didn’t get past the marbled and be-fountained forecourt of her Upper East side Brownstone. Why not? I have absolutely no idea.

On the final day of my stay in New York that year, we were all invited, myself, the McLeans, and David Evison (now accompanied by Jenny Durrant), for a debriefing drink at Greenberg’s Central Park West apartment. He was relaxed, in a thin shirt loose at the waist. I’ve described the conversation at length for the Artists’ Lives Archive at the British Library; in it, we all gave our responses to what we had seen and heard.

According to Greenberg, ‘De Kooning was a bore, Newman was a bore, Hofmann was a bore’ (‘an august, pedagogic bore’, he had said elsewhere). Apparently, everyone was a bore except Gorky, on account of his colourful Armenian presence, and Pollock, because he never said anything, unless drunk, and then it didn’t matter. Greenberg favoured the strong silent type, and disliked the artist-as-intellectual. He forgot to mention Lee Krasner, to whom he was indebted for much. He repeated his belief that Pollock was the most intelligent, the most ‘true’, because he knew where the pressures lay- from Picasso and Miro, chiefly- and what had to be lived up to. So, I think, did Gorky and Motherwell.

I recall saying that there seemed to be a polarity between the big Monet ‘Nympheas’ and the sketch for Matisse’s ‘The Dance’ both at MOMA, New York; that the former fused overlapping zones of colour, the latter relied on the power of contour drawing. Greenberg replied: ‘Yeah, but you’re forgetting what they have in common: they’re both empty in the centre.’ That threw me; but that’s where we were at, at least for a while. Everyone was making work that was empty in the centre, (literally so, but possibly metaphorically also) — Olitski, Frankenthaler, Noland, Dzubas, pushing incident to the edges, until the reaction set in, especially in England, where painters like Heron, Hoyland, Ayres, Durrant, Wragg, and others, including myself, began to balk at the strictures of Post-Painterly Abstraction in favour of a more full-blooded engagement with the stuff of paint.

‘Painters Painting’ documents the moment at which the Greenbergian hegemony, under attack from all sides, from disillusioned former acolytes like Rosalind Krauss, and sundry other academic art historians and critics in the pages of ‘Artforum’, began to disintegrate. Despite his own disavowal of it, the historicistic progressivism of the argument he made in his essay ‘The Cubist Collage’ in ‘Art and Culture’- that Picasso and Braque produced a series of masterpieces by resolving the conflict inherent in Cezanne’s espousal of trompe l’oeil illusionism in the context of form-creating, surface-hugging pattern (and the belief in the necessity and inevitability that this ‘advance’ seemed to imply) had stuck to Greenberg, and became one of many points on which he was being attacked.

Furthermore, the anti-European subtext also present in much of Greenberg’s project throughout the 1950s and 1960s (however emphatically he would have denied that there was such a project) came back to bite him in the form of the overt propagandising of Judd and Morris, and the anti-form, anti-composition, aleatoric games of John Cage et al.

The statements made by the surviving Abstract Expressionists featured in the film are, for the most part, unremarkable. Barnett Newman has this to say about the subject in painting:

‘The best distinction has been made by Professor Meyer Schapiro […] between what he called the ‘object matter’ and the subject. For example, people think Cezanne’s subject is the apples. Well, it’s possible to argue that that’s what it is, and for a long time I was very antagonistic towards those apples; I felt they were ‘super-apples’, they were like cannonballs…but Meyer is making the distinction between the subject of a work and the objects in the work, which should help people understand that even though my painting did not have any objects, it did not necessarily mean that there was no subject there.’

This, whilst seeming profound, is a trivial semantic quibble when set beside D H Lawrence’s note on Cezanne’s paintings.6http://degustibus.pbworks.com/f/Lawrence+on+Cezanne.pdf

De Kooning expiates, in his Dutch-inflected American English, on ‘der moutt’– the mouth- of Marilyn Monroe, and Motherwell explains how he arrived at the dualisms of his ‘Open’ series:

‘Chance is not a primary idea with me. Nevertheless, it is true that the ‘Open’ series was discovered entirely by chance. One day I put a small vertical canvas against a large vertical canvas; observing the smaller canvas against the larger one, I thought, what a beautiful proportion, and without a second thought picked up a piece of charcoal and outlined it on the larger picture.’

We’ve all done it: most notably, Braque, in his late ‘Atelier’ paintings of the 1950s.

The interview with Greenberg is more substantial. It reveals his thinly-veiled contempt for the neo-Duchampian pranks of Rauschenberg and Johns, and the artists associated with Pop:

‘When Duchamp made his cage of marble cubes that looked just like sugar lumps, representing or fashioning what could easily be duplicated, and fashioning it in a traditionally ‘artistic’ material like marble, and making marble look like an industrial product[…] Johns followed him by casting a flashlight and a beer can in bronze, and then painting them in some cases to look identical, so you couldn’t tell the difference between the bronze version and the original. The point of all that is supposed to be the point.

Lichtenstein and Warhol, they paint nice pictures; but all the same, it’s easy stuff. It is; it’s minor. The best of the Pop artists don’t succeed in being anything more than minor. The best art since Corot […] challenges you more. It doesn’t come that far to meet your taste.’

Greenberg continued to voice his disdain for academicised ‘far-outism’ and ‘avant-gardism’ in interviews and late articles, somewhat of a lone voice amidst the ‘triumph’ of Conceptual Art and Postmodernism.

‘The inexorability with which taste pursues is what avant-gardist art in its very latest phase is reacting to. It’s as though conceptualist art in all its varieties were making a last desperate attempt to escape from the jurisdiction of taste by plumbing remoter and remoter depths of subart — as though taste might not be able to follow that far down. And also as though boredom did not constitute an aesthetic judgement.’7Greenberg, C.,’Counter-Avant-Garde’, 1971

‘Just take a look at what these ‘postmodern’ people like and what they don’t like in current art. They happen, I think, to be a more dangerous threat to high art than old-time philistines ever were. They bring philistine taste up-to-date by disguising it as its opposite, wrapping it in high-flown art jargon.’8Greenberg, C., ‘Modern and Postmodern’, 1980

But the prevailing tone of his responses, that we had entered a phase of terminal decline, decadence and barbarism, where judgements of value in art, ‘qua art’, as he would put it, were seen as bourgeois evasion, was not peculiar to him alone. Susan Sontag, in ‘Afterword, Thirty Years Later’, of 1996, says this:

‘What I didn’t understand (I was not the right person to understand this) was that seriousness itself was in the early stages of losing credibility in the culture at large, and that some of the more transgressive art I was enjoying would reinforce frivolous, merely consumerist transgressions…we live in a time which is experienced as the end- more exactly, just past the end- of every ideal. (And therefore of culture: there is no possibility of true culture without altruism)…Something that it would not be an exaggeration to call a sea-change in the whole culture, a transvaluation of values- for which there are many names. Barbarism is one name for what was taking over. Let’s use Nietzsche’s term: we had entered, really entered, the age of nihilism.’

What took her so long, one is tempted to retort.

Charley Peters and Matt Dennis: ‘Painters Painting’: A Dialogue

CP: The first time I saw ‘Painters Painting’ was at art school. I was conflicted even then, knowing that there were ‘great’ painters in it, but struggling to focus through the intense seriousness of their tone. I knew I should have been taking great notice of what everyone was saying, but was also haunted by the reality that these artists felt so distant from me in their ‘importance’, and in the often humourless presentation of their work. Not many of them were especially relatable to the awkward 19-year-old me. As is the case with many classic works of literature, I wish there’d been more pictures…

These days, when I watch it, I’ve obviously long since learned the language that everyone in the film is speaking and have a better understanding of the world they existed in. Their world doesn’t actually feel much more relatable, but is less alien. I’m sure we’ll go on to discuss the problematics of the film, but looking at it now I do also feel a sense of warm nostalgia…there really are great painters in there, with interesting and useful things to say, and the film itself is nostalgic in its own way, a relic of filmmaking and of how we maybe once revered artists in a way that we no longer do.

MD: For me, ‘Painters Painting’ was a part of my education in art, profoundly so; it went a long way in helping me fall in love with abstract painting. My own fanboy mentality means that I’ve always been easily seduced by footage of artists sitting in their studios with stretchers leaning on the wall behind, with a soundtrack of an assistant off-camera somewhere going thunk-thunk-thunk with the staple gun; and if I’m really lucky, I’ll get to see a canvas being primed with a coat of white…to me, that’s all riveting, I’ve always lapped it up, I’m a trainspotter of abstract art. Arguably, I am in many ways part of the target demographic for something like ‘Painters Painting’, when the camera roams through studios…

So, there’s a sadness for me, re-viewing it forty years after I first watched it, knowing that I can no longer lose myself in it in the way I once did. The person I have become knows there’s too much wrong with it: too much that’s too partial, and blinkered, and laugh-out-loud ludicrous in places…

So many of the participants seem to believe they’ve been gathered together to celebrate a victory. The noise of the movie- of long sections of it, anyway- sounds on first hearing like a victory yell; but it’s actually a last gasp, a death rattle, and that, right there, is the pathos of the thing: we’re peering back into a lost world, a world of certain kinds of certainties, shall we say, that now couldn’t really be more uncertain.

CP: Yes, that’s it: the certainties. We simply can’t be certain in those sorts of ways any longer: certainties don’t exist in the way they once seemed to, at least, not in art, at any rate. So much is different in our contemporary sensibility- we’re so much more open to things being fluid and flexible, in every way, in how we interpret everything.

MD: I have remarkably mixed feelings about it. On the one hand, I feel quite moved whenever I’ve watched it: it brings back a lost world of bold and brightly-coloured artefacts, made at a specific historical moment; and I sense that for most of its participants, it felt like an immensely significant moment of becoming, at the very cutting-edge of advanced art. The movement to which they belonged was making its inexorable progress, they felt, ever onward, in a state of perpetual renewal…but on the other hand, it moves me, because we know, with the benefit of hindsight, that by the time ‘Painters Painting’ was released, this movement, this vanguard, was rapidly losing traction. These men, some middle-aged, some already old, are gathering to celebrate the rude health and vibrancy of something that’s about to expire.

MD: From the start, the film does its very best to strike a note of triumphalism. There’s the opening talkover by Philip Leider, who’d been Editor of ‘Artforum’ for much of the 1960s, delivered whilst the camera frame is filled with vertical black and grey stripes, before it pulls out to reveal we’ve been looking at the side of a building…

CP: It’s scary and pompous (laughter).

MD: It describes the vision of America bequeathed by the painters the Abstract Expressionists eclipsed- and we understand he’s referring to the Regionalists, to Thomas Hart Benton, to Grant Wood, and the like- as one of ‘fiddling rustics’; and apparently, the real, authentically American art only came about in the act of renouncing all that Americana. Only then could there be art of ‘real magnitude’.

Where ‘Painters Painting’ is on surest ground, and where it excels, I think, is in getting us to understand the context out of which all these paintings came, and what their makers’ aspirations were. All of the big names we hear from in the film’s first half express this same wish to distance themselves from what art had been prior to their breakthrough. Let me just leaf through my notes here…

Stella says ‘both Pollock and Hofmann came to terms in some sort of accomplished way with what had happened with twentieth-century Modernism, with European painting. They established American painting […] as something one could have confidence in. I didn’t have to worry about where I stood in relation to Matisse and Picasso; I could worry about where I stood in relation to Hofmann and Pollock.’

Newman, in response to his own question, ‘What can a painter do?’ explains that ‘the subject became the crucial thing to me in painting; not the technique, not the plasticity, not the look, not the surface; none of these things meant that much. The issue for me, for Pollock, for Gottlieb, was: what are you going to paint?’ He’s at pains to emphasise the rupture with all previous art that his and the paintings of his contemporaries represented: all previous painting was the work of ‘choreographers of space’ who made ‘tactile art’ or ‘narrative art’; whereas his, and that of his fellow abstractionists, was ‘visual art’, to be seen ‘on a universal basis’. What was more, ‘all these issues, to do with whether it’s American, or whether it’s painterly, are false issues raised by aesthetes.’ In other words, the profundity and originality of Abstract Expressionist painting were such that this new American art was a universal art, that somehow had managed to transcend all the questions that historically had been levelled at painting.

CP: It’s striking how for all of them, for Stella, Newman, and Greenberg, Pollock was the touchstone, the hero of the creation myth of Abstract Expressionism. American painting begins with Pollock, the myth-maker, the ice breaker.

I had to look it up online just now to check, but sure enough, Pollock died in 1956; a long, long time before ‘Painters Painting’ got made. You’re right, in many ways the film feels like a kind of headstone for him: there’s a sentimentality there, the sentimentality of the Pollock myth. I truly wonder how many of the painters in the film genuinely felt so reverentially inclined towards him: several of them were his contemporaries, weren’t they? I don’t think they were necessarily led by him, or following what he was doing. And with that question in mind, how we could have benefitted from Lee Krasner being in the film! Maybe she declined an offer to be in the film, we don’t know.

MD: I’d be tempted to think, what offer? There’s no Krasner, and although Helen Frankenthaler’s in there, she’s given fantastically short shrift in ‘Painters Painting’: no mention by any of the men of the painter who by general agreement had been, through her incorporation of Pollock’s pouring techniques into her ‘soak and stain’ aesthetic, ‘the link between Pollock and what was possible’, and then there’s the blatant tokenism of her inclusion in the film, as a ‘lady painter’. Which brings me on to ask- we talked recently about your idea of approaching ‘Painters Painting’ via Linda Nochlin’s famous essay, ‘Why have there been no Great Women Artists?’ of 1971. Did you make any headway there?

CP: I thought I might be able to formulate a position around that essay based on de Antonio’s omission of any women artists except Frankenthaler from the film; but I ended up thinking myself into a corner. What I’ve realised- and this might well be the subject of a whole other article- is that it really only makes sense historically to consider Nochlin’s essay in relation to ‘Painters Painting’, as it was published in 1971, only a year before the film came out. It scrutinises the barriers that prevented women and minority artists from achieving great success in the art world, and it points the finger at the lack of access for women to art education; it takes issue with notions of craft as something passed down through the generations from fathers to sons. Nochlin insisted that her investigations into art world inequality would serve the arts as a whole; her asking why women artists had been systematically excluded from the historical canon would prompt an investigation of context for all artists, resulting in a more authentic and intellectually rigorous assessment of art history up to that point. These ideas are reflected in an appraisal of ‘Painters Painting’, which essentially paints a picture of a male-dominant culture of painting.

However, there are some contemporary complexities to acknowledge. When defining the female experience in the art world of the time, Nochlin wrote:

‘The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education.’

It’s great that she could write that in 1971 – radical and insightful – and it was doubtless true; but I couldn’t find a way to use it as critical framework now. It’s no longer a robust enough feminist critique; Queer Theory and contemporary identity politics around gender make it problematic to talk about hormones or menstrual cycles or internal spaces in terms of a universal female experience. It started to feel impossible to me, trying to thread things together in a way that wouldn’t be extremely contentious and outdated. This is a shortcoming of mine that I freely admit to, I feel that I’m not well enough versed in a contemporary feminist art criticism that does more than consider a reactionary, patriarchal model, and embraces all women, not just the biologically assigned. It’s no longer appropriate to see feminism as a case of patriarchy on the one side, ‘women’ on the other.

MD: Let’s face it- fifty years on, even the most radical, forward-looking politics of an era are bound to look outmoded. I did a bit of digging around this question of bias as well: I wanted to understand how it was possible for a director like Emile de Antonio, who had what at the time would have been viewed on the left as impeccable political credentials- his documentary, ‘In the Year of the Pig’, from 1968, was highly critical of America’s involvement in Vietnam, and he would go on to make ‘Underground’ in 1976, which consisted of clandestine interviews with a radical-left revolutionary group, the Weather Underground- how it was possible that he could deem it appropriate that ‘Painters Painting’ should have just one woman artist in it- Frankenthaler- and further, that he could deem it appropriate to ask her ‘Is it hard for a woman to be a painter?’ and then leave it at that, rather than do what we would all now see as the obvious thing, namely, take a small but significant step towards remedying the situation his question only pays lip service to, and include many more women in his film. What I found was a very interesting essay, published in 2001, ‘The Formation of Feminist Consciousness among Left- and Right-Wing Activists of the 1960s’, by Rebecca Klatch; in it, she gives a sense of how, as she puts it, amongst the various radical-left groups of the time, ‘the prevailing universe of political discourse excluded women’s experiences from the pool of legitimate grievances’. The essay includes excerpts from the many interviews she conducted with women who’d been members of these groups, and most of them say, in so many words, that the men dominated discussion and creation of policy, and insisted that women’s demands for equality get in the queue, so to speak, behind poverty and race, which were seen (by the men, at any rate) as the ‘real’ concerns meriting political action. This, then, perhaps gives a sense of a wider context within which a self-identifying radical like de Antonio thought he could get away with such astonishing levels of bias.

CP: It is very, very surprising, from him in particular, when you consider how critical, how oppositional his other works in film were. I would have expected more, to be honest, of someone so politically aware; to have allowed only one woman in, when there were so many female contemporaries of Frankenthaler that one knew of, that easily matched her level of success, and were equally prolific- and they’re not there. It’s very strange.

Everything he had made in film up to that point had such a strong political content, and then he makes ‘Painters Painting’ and he says he was very, very keen to keep the painters separate from the dealers, the collectors, the people whose job it is to promote the art, because there’s something about the apolitical purity and autonomy of abstraction that attracts him, which is so surprising. For me, to find that this political animal is actually a formalist and an exponent of art for art’s sake, a proselytiser for it, is absolutely astonishing. In the interview he gives to ‘Artforum’ in 1973,9‘Artforum, March 1973 he says ‘the inconsistency of having left-wing politics as I do, and liking the paintings of Jackson Pollock, Jasper Johns and Frank Stella is not, to me, contradictory’. And he goes on to say, the painting in ‘Painters Painting’ is apolitical, is concerned with painting, not politics; with paint, canvas and objects. To me, I have to say, ‘Painters Painting’ feels like a homage, to a circle of male artists that he considered his friends, and the wish to pay homage clearly clouded, or at best coloured, his judgments.

MD: He seems to be trying to make a distinction between the perfidiousness of the market, and the purity of these particular practitioners, working within it. He seems to be arguing for the innocence of the painters, and for their not being dirtied by association with anything other than painting.

CP: But what did you think about that? Because that feeds into so much of that mythology of the Abstract Expressionists, and of male genius, that they were somehow godlike or other than human or beyond everyday experience; you know, that they live and breathe paints and that’s their only interest in the world. It’s interesting, I think, because it relates to what Nochlin said in her essay- even though we’ve already established that it’s not an entirely useful framework for looking at this film- speaking about this idea of genius as being a kind of macho thing.

Going back to the Nochlin essay: those ideas were out there then, that women hadn’t had enough access to education or institutional validation; but I do think her essay, at points, feels out-of-date now. It has its uses, as a sort of peer-led critique of the film, but in its own way, it feels ridiculous now.

MD: You’d go as far as calling it ridiculous?

CP: Well, maybe not ridiculous, but a lot of work like Nochlin’s, and later, second- or even third-wave feminist critique, feels irrelevant or at best outdated now, because of the problem that it’s all essentially binary. And we are simply unable to see things in these terms any longer: binary, and built on biology.

Fifty years on, we have to temper our responses with an awareness that the available ‘thought-space’ of the time, if you like, wasn’t able to accommodate notions that seem to come so naturally and easily to us now. Consciousness has expanded massively, in terms of awareness of these issues. More is conceivable now.

CP: I’m not sure how deliberate a decision it was on de Antonio’s part, but this triumphalism that colours the first half of ‘Painters Painting’– very noticeably so, in the case of Newman and Noland- seems to give way to an entirely different sensibility, in an entirely different register, with the introduction into the mix of Rauschenberg, Johns and Warhol. Rauschenberg and Johns, in particular, bring humour into what has been, up to that point, a cocktail of bluster and macho cowboy swagger, a pretty much entirely humourless enterprise, and in some places, a rather boring one. Old, stuffy men, overly earnest- although, to give them their due, they’re entitled to a measure of earnestness, they’re great painters, there’s not a single dud amongst them, which is why I loved watching it, there’s amazing art in it- but to put it simply, it feels to me as if the film was made too late; the era it looks to celebrate was already over. There’s a sense that, for the participants, Abstract Expressionism was still this radical form of painting that was shaking up the art world; but these beautiful paintings, filmed in colour- they already exist, they’ve already been made, and as we look and listen we’re pulled from the past of the paintings into the present of the artists’ studios, and their talk, and we’re meant to see them as forward-looking, but it’s being done retrospectively, so to speak; the interviews situate the paintings in the notional ‘present tense’ of the artists’ verbal descriptions, but there’s this sense of slippage about the film’s timeline, as if we’re being encouraged to view what had happened as if it is happening. ‘Painters Painting’ should have been made in the mid-1960s; there were great Abstract Expressionist works still being made then, I don’t know why de Antonio waited so long, because by the time the film was released, advanced art had mutated into far more reflexively self-aware forms. To be fair, though, Stella has his moments: I enjoyed his soundbite, where he talks about making work that critics couldn’t criticise. He’s playing games, and in these places where the playfulness is felt, there the film feels radical; but there just isn’t all that much of that sort of thing, alas. I’m not saying one can or should expect art history to be amusing, or funny; but in the context of a documentary film, as a means of engaging us, of helping us enter the studios and the mindsets of the painters of a particular historical moment, there’s a place for warmth. Some of ‘Painters Painting’ is cold, and dry, and arrogant in places, like a cocktail party with a great many people we might not particularly feel like talking to…for me, I say thank God Rauschenberg and Johns were in it; they inject a level of self-awareness into what otherwise would have been a quite tedious melange of guy-chat.

MD: Would you single particular segments out as being dull and tedious?

CP: Well, I’m being slightly tongue-in-cheek. It’s hard: some of the content is interesting, but the delivery is dry and dull. I found Newman difficult, not to say a little bit terrifying; like being stuck- maybe let’s leave this out of the interview transcript?- with a dull uncle who has absolutely no idea how to talk to kids (laughter). And the collectors who appear: they’re dull, also.

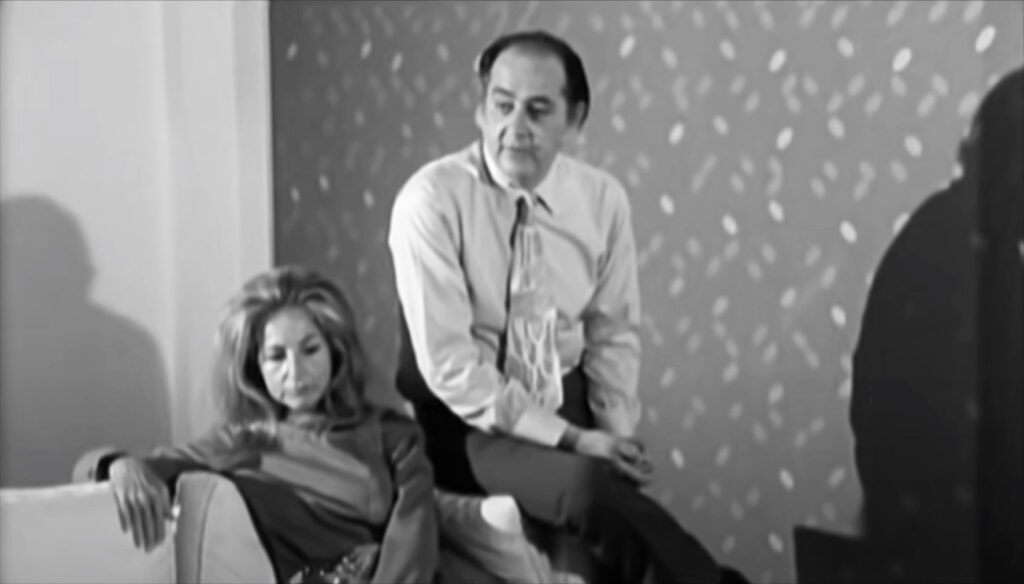

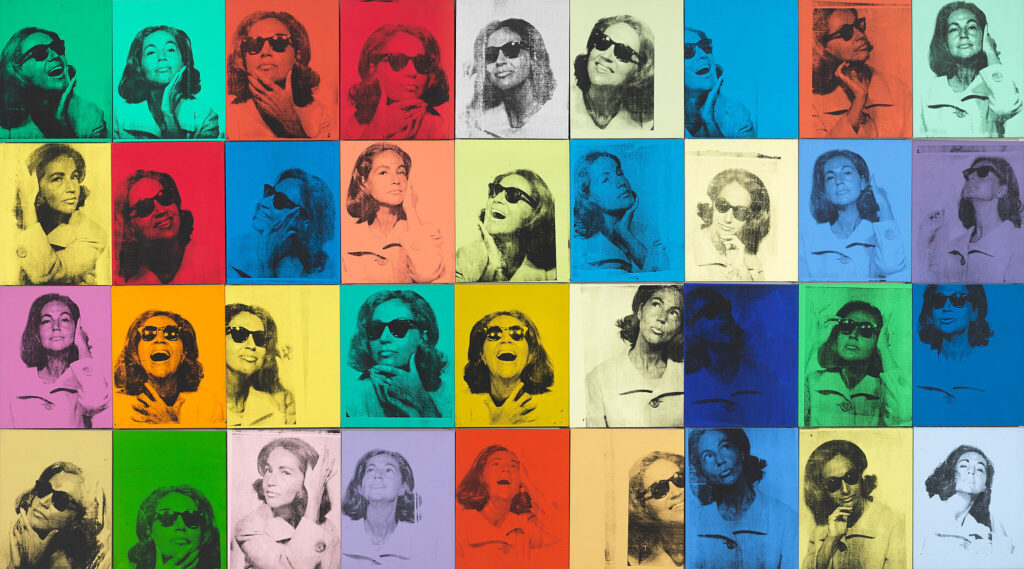

MD: That would be Bob and Ethel Scull. Ethel doesn’t get to speak a great deal- which, in the man’s world of ‘Painters Painting’, shouldn’t surprise anyone- but in fairness to her, when she does, telling the story of her day spent with Warhol, dashing around the photo booths of Times Square, getting her picture taken in different guises to generate the imagery that Warhol silkscreened on a multicoloured grid, she brings it vividly to life. Bob Scull, meanwhile, brags about how his patronage was the career break that set several of the painters free from the grind of day jobs; he pats himself on the back for rescuing Larry Poons from flipping burgers- and then we cut to Poons, who proceeds to rubbish that assertion, asking ‘What the hell is Bob Scull talking about? It never happened like that.’ It’s hilarious. I wouldn’t call Bob Scull dull, so much as delusional; he clearly has a greatly inflated sense of his own importance as a catalyst for these artists’ careers.

As far as what you say about Newman goes, I agree with you; he pontificates. But in relation to the excellent point you make- that the timeline of ‘Painters Painting’ seems to suffer a kind of slippage: well, we’ve arrived late at the party, it’s very nearly over, all the bottles and glasses and plates have been cleared away, the ashtrays have been emptied, people are already hailing cabs…

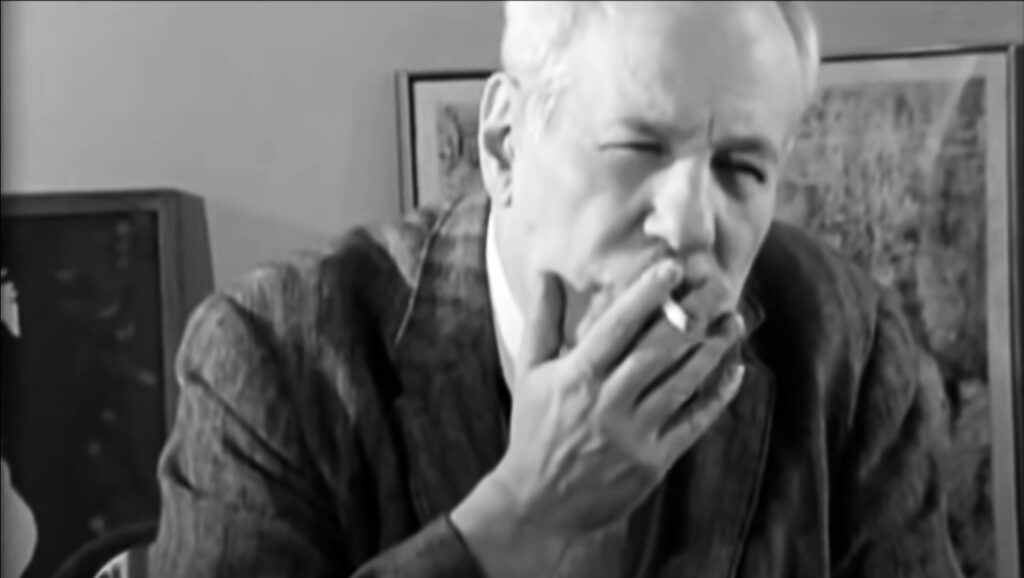

It’s called ‘Painters Painting’, but there is literally no painting being done in it at all- unless you count the segment of Hans Namuth’s famous footage of Pollock painting from the early 1950s that gets included. The film’s title just happens to trip off the tongue easily, and that’s about it. It should have been called ‘Painters Pontificating’– God knows there’s enough of that- or even ‘Painters Puffing’; there’s a cocktail party or saloon bar atmosphere to so much of it, and the amount of smoking in it is just phenomenal- Newman gets through half a dozen fags in his time in front of the camera; Motherwell sparks one up, Greenberg’s got one on the go at all times; Johns puffs away; Stella, Olitski and Henry Geldzahler are on the cigars (laughter). It’s not a movie about painting, it’s a movie about having painted.

CP: Exactly. It’s happened; but we missed it. And instead, we’re treated to a post-coital fag with the guys (laughter).

MD: I do think we have to credit Emile de Antonio with making a clever film: because every time it seems as though ‘Painters Painting’ is sending us in one direction, he does something to monkey with that single reading. Early on, amid the fanfares and the chest-thumping triumphalism of the Ab-Exers and their apologists, he gives us Hilton Kramer, a notably conservative, let’s say reactionary, critic; and by having him appear, straight away we’re put on notice that there’s going to be some pushback against the chorus of approving voices lauding abstraction. I will say, Kramer comes out with this fantastic phrase: he describes the prestige awarded to Pollock as ‘the heroism of the big breakthrough’. And he doesn’t stop there. He calls Pollock’s work, and that of his contemporaries, ‘a mopping-up operation on the School of Paris’, and ‘the last gasp of European Modernism.’

CP: As you’ve mentioned earlier, this pops up a few times in ‘Painters Painting’, this notion that these artists are reacting against Matisse, Picasso, Braque. Frankenthaler talks about playing off Cubism, and I imagine them all as having this sense of European painting, of European abstraction, from the beginning of the twentieth century to the 1950s, and of the formal language of painting being taken apart and reconstituted in radical ways. The sense is there in the film that European art enabled them to make the paintings they were to make, but that it also functioned negatively, as something for them to feel disassociated from, and freed from in order to do exactly what they wanted, and to do it so much bigger, and well, better. That was the belief, at any rate.

MD: For the Hilton Kramers, Abstract Expressionism is this attenuated, derivative offshoot of the great European tradition; a reiteration, an extrapolation of certain innovations rooted in Cubism, at monstrously enlarged size. For that sort of critic, European Modernism would have derived whatever merit they saw it as having from its connections to a tradition of Western representational painting; and their dismissal of Abstract Expressionism would be grounded in the argument that it existed at so many removes from the wellspring of real quality in Western art that it was a hopelessly decadent form of mannerism, doomed to run its course and disappear from history.

MD: Hilton Kramer appears to be there in the film to attack Abstract Expressionism from the right, if you like, from a reactionary standpoint; and on the other hand, we have Rauschenberg, Warhol, and Johns, attacking, or at least, undercutting the triumphalism from the left, from a radical, in some ways anarchic perspective.

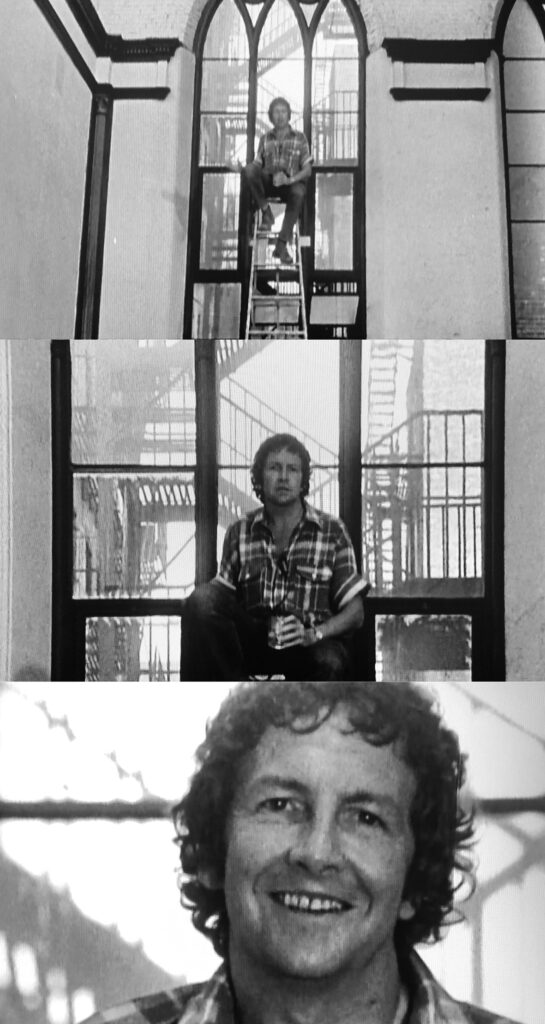

Rauschenberg is dazzling in ‘Painters Painting’. The way he’s presented, or, more likely, opted to present himself, up the top of that stepladder in the stairwell, with the big windows behind…when I watched that sequence again, I thought, it’s not clear whether he climbed up there from below, or whether he flew in from above and alighted on it. He’s like this exotic bird from another climate, or another dimension altogether.

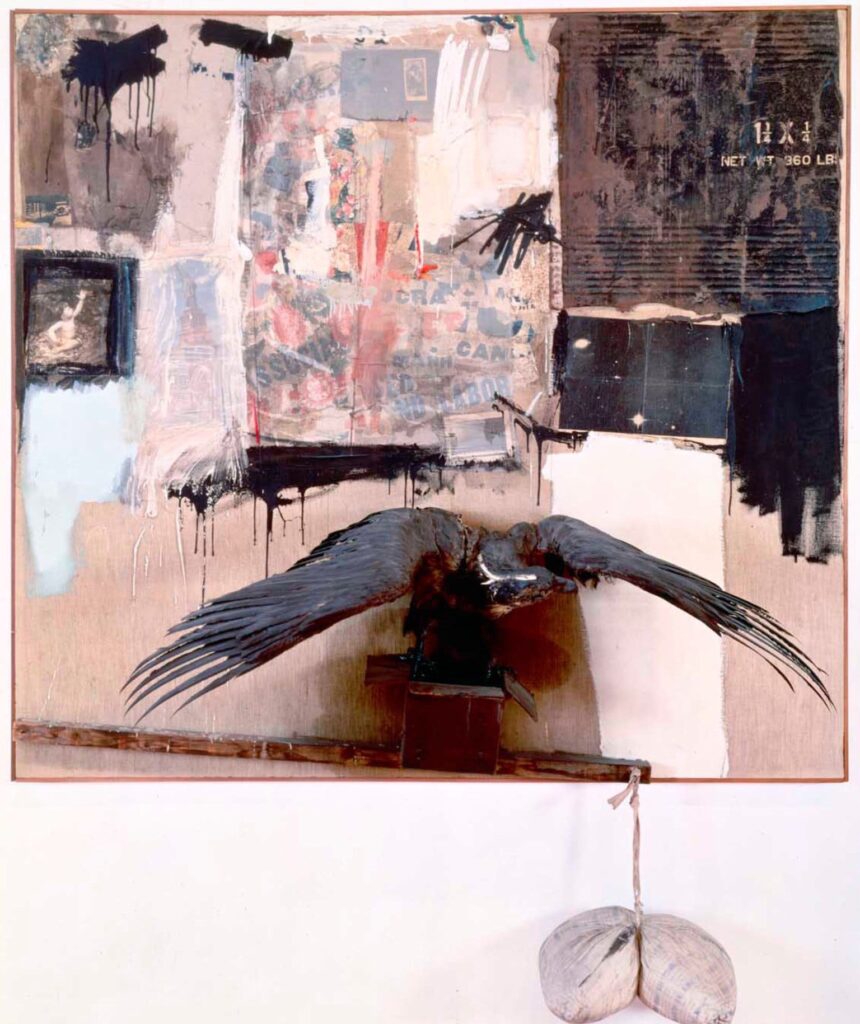

CP: Like the eagle in ‘Canyon’!

MD: Isn’t he, though? He’s like an extraordinary found object introduced into the canvas of ‘Painters Painting’. The charisma of the man is overwhelming, you understand straight away why he was spoken of in tones of hushed awe by so many people; there’s so much keen intelligence there.

As for what he has to say: he wields his wit like a rapier, and just runs the Ab-Exers through with it. He talks about his approaching De Kooning, to get his consent to the idea of the ‘Erased De Kooning Drawing’, and it’s fabulous, the way Rauschenberg describes it: he’d thought about making the drawing himself, and then erasing it; but, as he explains in his wonderful Texan drawl, doing that would just be ‘fifty-fifty’ and that he needed something that was already art when he first came to it. He describes it all so charmingly, he just carries you with him, and makes it seem like the most natural activity in the world, vandalising a drawing by one of the standard-bearers of Abstract Expressionism.

Of the Ab-Exers in general, he has this to say: ‘What they and myself had in common was touch. I was never interested in their pessimism or editorialising. You had to have time (or as he says it, ‘taaaaahm’) to feel sorry for yourself if you were going to be a good Abstract Expressionist. And I think I always considered that a waste.’

CP: It’s poignant that he appears where he does in the film, and that the drawing he chooses to erase is a De Kooning. It’s at this point that we understand that things have moved, are moving on, and that Rauschenberg is the new model of ‘the artist’– the ‘other’ to De Kooning’s straight white male- and you’re right, this makes him seem otherworldly amid the context of the bar-room boys’ club of ‘Painters Painting’, backlit atop the stepladder against the high windows, like an archangel.

We have to see his talking about ‘Erased De Kooning Drawing’ as a very deliberate inclusion, a provocation even, in terms of the storytelling within the film- it’s there to give a sense that a great deal of great painting had happened before it, but that it marked a new departure, a point at which the culture of art changed its direction and its orientation.

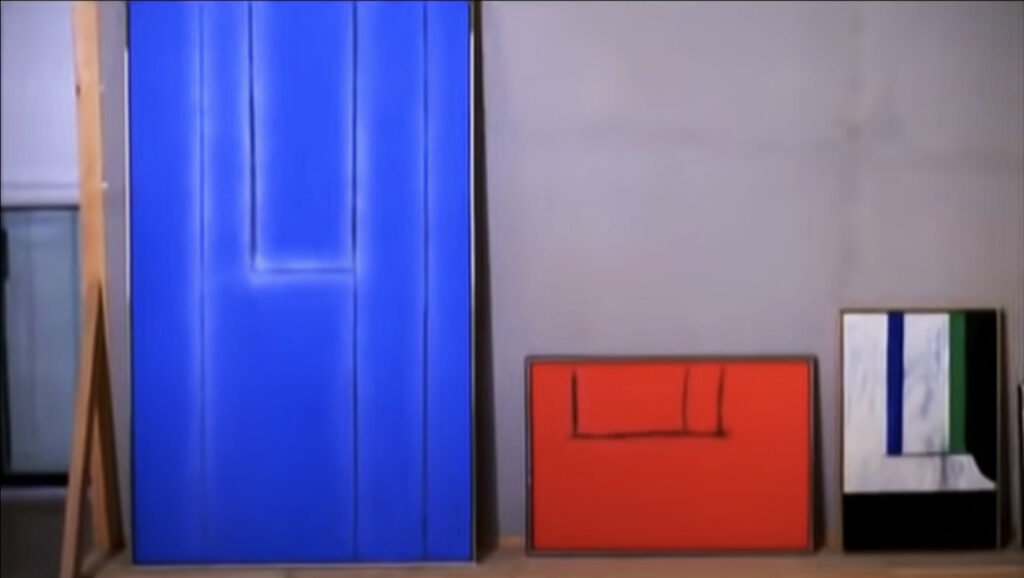

MD: You’re absolutely right- the first half of ‘Painters Painting’ builds on this narrative of great abstract painting having been done; the second half seems largely devoted to pulling that narrative apart, and the pivot point between these two contrasting approaches is Kenneth Noland’s long segment. He’s in the studio, cross-legged on the canvas chair in the crisp black shirt and chinos, smoking, the very picture of calm command; and yet, what really comes across in Noland’s time on screen is how defensive, how much on the back foot he is, despite the apparent confidence in his own method, that of ‘one-hit’ painting: ‘If you were in touch with what you were doing, you only had to do it one time.’ There’s something in the way he talks about how his own work should be viewed or assessed or criticised- by himself, presumably, as much as by others- that makes me think he’s trying to convince himself, and that he’s not quite up to it. He says ‘there’s the best taste, the right taste, the real taste…the real thing.’ He’s reduced to quoting the Coca-Cola slogan, of all things; he wants to broadcast confidence, but it’s just not there. Watching him, he reminded me of someone having their furniture repossessed by the finance company, vainly protesting as his sofa is being carted off down the stairwell.

He’s surrounded by paintings in progress, lying unstretched on the floor; and these are not- what shall we say?- not very giving paintings. They’re all travelling on this narrow, straight track in the direction of Greenberg-endorsed higher-than-high Modernist historical inevitability; they’re massively horizontally-extended colourfields, and all the action is banished out to their masking-taped banded edges. I thought, how amazing it seems now, that for Noland, for Olitski, for Greenberg, back then, painting was fated to travel along this ever-narrowing pathway towards- well, what? It seems impossible, now, to imagine how anyone could have believed, then, that this process could continue to sustain itself. And ‘Painters Painting’ brings this home, by accident or by design or by both: this feeling of something being drawn out, attenuated, pulled and pulled and stretching thinner and thinner…

CP: I see it as an arrival at a tiny, final, single point: the full stop at the end of an extraordinarily long sentence, if you like. And beyond it? A new chapter? An entirely new book? This group- this school of painters immortalised in the film: there aren’t really any more schools after them, are there? From this point, we enter the era of ‘everyone, just do your own thing’. Everything opened up, and none of it’s ever come back together again after that; never re-grouped along a straight line…

MD: From High Modern to Postmodern.

CP: ‘Painters Painting’ is significant, for me, because I honestly believe it marks the absolute end point of a particular history of art. All of twentieth-century art had been movements, schools, groupings of artists whose members lived and worked and talked alongside their peers, helping each other, sleeping with each other; but with the painters of ‘Painters Painting’, that stops. We don’t see it again. That’s it, done.

MD: Up until the point in ‘Painters Painting’ where de Antonio introduces the counter-narrative, we’re travelling on the High-Modernist express, further and further into refinement of pictorial art, more and more rigorously and severely mapping out the territory peculiar to it, excluding anything extra-pictorial; and the ultimate development of this tendency appears to be Noland’s paintings, and Newman’s. What we don’t get are any fully-paid-up Minimalists: No Serra, no Reinhardt. The High Modernist express doesn’t travel as far as those sorts of destinations.

‘Painters Painting’ is the very last gasp of an assumed consensus, or what philosophers call a ‘totalising metanarrative’. In other words, a single, unifying theory; in this case, one that seeks to set the terms for all possible manifestations of onward progress in abstract art, put forward by a single, brilliant critical thinker, Clement Greenberg.

There’s no real sense anywhere in ‘Painters Painting’ of where painting could or should go next- not that’s stuck in my memory, anyway. There is, though, this unmissable sense of what you’ve so aptly called ‘slippage’– between what certain segments of the film are encouraging us to feel, namely, that we’re privileged eavesdroppers or onlookers at the sites of momentous creative events, where art history is being made as we look and listen, and the actual sensations these segments evoke, which are more often than not a sort of forlornness, a desperation even…

CP: That’s why I say that the present tense that ‘Painters Painting’ captures feels awfully like the past tense; and there’s no sense of a future at all.

MD: Clearly, there’s this tacit acknowledgement that it’s a hell of a lot easier to talk about what Pollock and Hofmann once offered in terms of permission to start afresh, than to find something to say about the narrowness and barrenness of, say, Noland’s painting in the ‘now’ of the movie. What did he have to offer, by this point, other than the extraordinary elongation of his paintings? He’s working on these sometimes twenty-plus-feet-long bolts of canvas, with heights of just a couple of feet. I see these as the material manifestation of an idea we’ve been airing here- that of an endgame for Modernist painting, drawn out longer and longer…when formal invention peters out, all that’s left is outrageous distortion of the format. Okay, it was ten feet long before; let’s see what twenty, thirty feet looks like…

And there’s the sequence in Stella’s studio. He’s talking about one of his ‘Protractor’ paintings that he’s just worked on, which is leaning up against the wall behind him; he’s describing his working methods, how he’s trying to get the colour to travel, by running it in these bands and arcs; but it only travels in the most literal sense, in these single, unmodulated hues, it doesn’t pulse, or expand, or contract, or suggest, or express. It’s impossible to shake the sense of someone flailing around, trying and failing to get working practices that he’d leaned on for the previous decade to carry him further. It’s all looking so barren, so tediously literal.

CP: Yes, they are barren. The film’s opening monologue has prepared us to see paintings that have changed the bloody world; and then we’ve got the ‘Protractor’ paintings being wheeled out, presumably to help that argument, and, well…there’s something of a mismatch there. The level of energy and the level of ambition in these Stellas- I wouldn’t say they exactly match up to the promises made in the opening narrative, or what the painters featured in the film’s first part are talking about- the way that Pollock paved the way for the complete reshaping of painting’s language. There’s nothing there in Stella’s arcs and curves: there’s no inwardness, no interior to these works, they’re measured, controlled, prescribed, and just not particularly interesting. Within the film’s storytelling, they just don’t make a great deal of sense.

MD: So much that followed after this point- such as Stella’s subsequent development, off the wall, into what he called ‘two point seven dimensions’ and crazed colour- feels like a necessary repudiation of all the sermonizing in ‘Painters Painting’. Painting couldn’t thin out, or narrow down, any more than it already had; so it became multifarious again.

CP: This question that hangs around our readings of ‘Painters Painting’– the question of how far de Antonio was looking to go in dismantling the narrative the first half of his film has been building- will never be settled, because he is long gone, and we can’t ask him. Looking online hasn’t helped me, because it’s surprising how little is out there about ‘Painters Painting’; close to sod all, in terms of clues about his intentions, or serious criticism of the film from any quarter.

I would love to know, definitively, what he had in mind; I would love to know how aware he was- and his painter friends too, for that matter- how aware any of them were of the alternative readings of the art history they believed they were busy writing. We’ve got the benefit of distance; we are in the privileged position of knowing where art went after these interviews were filmed. Who knows? Maybe all the participants sensed, on some level, that they were running out of steam; maybe de Antonio sensed it.

MD: As you say, these questions will never be settled. I happen to think that you don’t get to be as pre-eminent in your chosen field as the painters in the film were, without a healthy dose of blithe self-confidence, bloody-mindedness even; you don’t get to work in the ways they did, for as long as they did, without a voice inside your head that says, ‘Wherever I’m going, that’s where art is meant to go…’

I marvel at that kind of mindset as regards art, because for so many people now- myself included- I think the outlook we all share can be summed up as one of ‘part true believer, part arch-sceptic’; and I think something in the structure of ‘Painters Painting’ resonates with that conflicted outlook. Every time the film seems to be travelling in one unwavering direction into painting’s territory, and paying homage to it, it gives a sudden lurch, and slams into reverse.

We all understand that lurching between two positions now, and identify with it; speaking for myself, I find painting fascinating, utterly gripping, one of the things I most love being involved with, and paying attention to; and at the same time, the excesses of it, the assumptions made about it, drive me half-crazy from frustration with it. We’ve all come a long way, and we all want to prick the sort of bubbles of pomposity that get blown throughout ‘Painters Painting’. We can’t watch it or hear it again with the eyes and ears of 1972.

CP: Warhol is an unusual addition to the mix: a strange name to have added to the guestlist for this particular painters’ party.

The sort of painting that, say, Ad Reinhardt had been making, which was painting entirely stripped of the sort of visceral subjectivity we associate with the Abstract Expressionists- by omitting that, ‘Painters Painting’ over-privileges the New York School, and makes them, in the absence of any significant comparisons, appear more radical than they really were.

The story of twentieth-century art is the story of the removal of the subject from painting, thereby rendering painting itself as its own subject; with Pollock, the great prophet of painting-to-come, we have a kind of ‘year zero’ of painting, the absolute up-ending and rejection of all pictorial conventions. But then, along comes Rauschenberg, erasing an abstract work, and introducing images again; a dry-run for Warhol’s use of mass-media imagery. ‘Painters Painting’ feels like a re-staging, in miniature, of this segment of art history: in the film, the abstractionists are in the ascendant, but are then upstaged, gently mocked, by Rauschenberg, who wipes the slate clean; and then comes Warhol, detached, ironical, blank…

MD: ‘Detached, ironical, blank’ says it perfectly. Do you remember the segment where he’s trying to interview Warhol and Brigitte Polk, and he asks a question of Warhol, and Warhol just turns to Bridget and says ‘Oh gee, I dunno.’ And it’s hilarious, because de Antonio is really quite annoyed, and he yells, ‘Right, cut!’ because he doesn’t want him to come out with any of that trademark evasive Warhol bullshit; he wants Warhol to give us the lowdown in the same way that everyone else in the film has been trying to do, and Warhol is not doing that because he’s Warhol and he won’t step out from behind his mask of blank indifference, of complete reluctance to engage. And yet we know that de Antonio and Warhol were great friends, and that the respect flowed both ways. I found that surprising. It doesn’t follow the script, if you like. De Antonio says in his interview with Artforum, in which he goes on the record about ‘Painters Painting’, how impressive as talkers Newman, Johns, all of them were, and how he wanted as much of them in the film as possible because they spoke so eloquently and so well. And then there’s Warhol, just giving him the same slippery semi-catatonic treatment he gave to everyone else who tried to get sense out of him. That’s another thing that doesn’t quite add up for me.

CP: In a way, that’s brilliant. It’s great that none of it really adds up. Even fifty years later, we can’t really demystify it, can we? It’s enigmatic and curious and frustrating.

I think there are howling contradictions here, and blind spots. In the Artforum interview, he describes conceptual art as a symbol of exhaustion; but you will find so many commentators who argue that Warhol, whom de Antonio reveres, was the conceptual artist par excellence, who, by undercutting the profundity of the artist’s autographic mark, by reducing painting to serial silkscreened photographic reproduction within a matrix of decorative brushwork, delivered the coup de grace to a certain idea of painting. To me, it’s glaringly obvious that’s what Warhol did, or was trying to do. And yet, de Antonio is so approving of Warhol. At the risk of going off-topic here, I think it’s worth our trying to understand what Warhol meant to de Antonio…

MD: For de Antonio, Warhol could do no wrong, both in his painting and his films; but with a flick of the finger, he (de Antonio) dismisses so many other people, like Hollis Frampton and Jonas Mekas, who’d crossed over from paint to film. Hollis Frampton was a good mate of Stella’s, they’d been roommates together at Princeton, so they’d known each other since the beginning, and Frampton had taken this path from painting into film making; and de Antonio is just really dismissive of it all, and of Artforum as well:

‘I think one of the reasons Artforum is in such a coy, artsy and academic way, searching out all kinds of crap in film is that most of the filmmakers you are dealing with are failed painters, or filmmakers who think like painters or aspire to a painting scene. People like Hollis Frampton, and the people who seem to amuse Annette Michaelson and film fleas like Jonas Mekas are essentially failed painters. They came to film out of desperation. They have all the same feeling towards visual material that the painters who had succeeded in their art. What they do doesn’t work in film. The idea of literally transposing exhausted painting ideas into film is a boring idea. And most of the people doing this are painters.’

So, what really gets de Antonio’s goat is the idea that painters-turned-filmmakers are taking concepts that worked in painting and having them fail, as they must do when they’re transposed into film. De Antonio clearly despises this sort of aspirational pretentiousness. And on the other hand, Warhol, who, as de Antonio said, is going back in his film work to the very beginning of film, back to the basics, back to the raw stuff of film making, wins his approval. And I think it’s Warhol’s lack of pretension and aspiration. De Antonio says Warhol’s first films were static; it was exactly like the birth of film, and then Warhol learnt how to move the camera, so you got a little more action…and then he learnt how to synchronise the sound. De Antonio approves of the fact that Warhol is a primitive of filmmaking, almost an idiot savant; and that greatly appeals to him. Why would that be, when so many of the other artists in the movie, all of them, perhaps, are such sophisticates and eloquent talkers about their own work and about abstraction generally?

CP: He’s very positive about all those films of Warhol’s. De Antonio said of him, ‘I noticed his technique was primitive. This was early in his film life. It was refreshing.’ He separates Warhol from some of the other filmmakers that he was talking about, and I wonder if that’s because Warhol was an artist that was making films, and not an artist-turned-filmmaker.

MD: That’s a very interesting distinction. I think you might have put your finger on something there.

CP: He’s lauding Warhol for his purity, that he’s gone back to the most basic kind of filmmaking. It doesn’t move, doesn’t have sound, it’s black and white. And I suppose when you go back that far into a medium like film, as you run time backwards, you come right back to the material itself, to the celluloid and the cutting and the splicing; film as physical material, to be worked and shaped. And then slowly and incrementally, Warhol introduces new aspects to his films, and it feels almost as if that’s like being in the studio, mixing paint on a palette, where you start with one colour and then you add another one. The film is the paint. De Antonio’s talking about Warhol’s process in the same way that he might talk about a painter making a painting. Warhol’s not dealing with the technicalities of framing the shot, or the decisive moment, or any of those other things that you might expect to be considering when you’re talking about or critiquing a film. Again, he’s applauding the purity.

MD: I’m going to suggest that it’s in large part Warhol’s influence that lends ‘Painters Painting’ its strangeness, its open-endedness. Not the influence of what you call Warhol’s ‘purity’, but his sheer resistance to a committed or editorialising stance of any kind, which is either going to enchant or infuriate. De Antonio seems to be saying, ‘Here it is. Make of it what you will.’

CP: I agree: nothing is clear, conclusive, cut-and-dried. In the Artforum interview, de Antonio makes the point that Abstract Expressionism had run into the wall, had run itself down to almost nothing, and that it needed the sort of kick in the pants that the arrival of Rauschenberg and Johns offered, their ‘anti-art’, their opposition to all that subjective expression. De Antonio sees them as a re-energizing force for painting, which had become moribund. And yet he coins this fantastic phrase when talking about them, and Poons, and Stella: ‘You don’t hear the drum of hoof beats behind them.’ In other words, there’s no one following on after. So, I’m not sure how coherent his total position is, how optimistic or otherwise. I can’t quite glean whether he feels that the job that Rauschenberg and Johns and Warhol did, violating the taboos of abstract painting, really opened things up again and led anywhere. I’m not clear.

His friends among the Ab-Exers took de Antonio a certain distance, and then he went further than any of them in embracing what Johns, Rauschenberg, Warhol were doing. But I think the reason that ‘Painters Painting’ is in so many ways so inconclusive is that he really had no clue what might follow after, in terms of painting. The film ends where his grasp of his subject ends; and it ends with this shuffling art-crowd, picking their way through the space of a museum, echoing the way a cinema audience shuffles out once the film is ended. It is, quite simply, bizarre: a pack of bemused-looking spectators looking for all the world as if they’re inspecting alien relics…what a contrast with the triumphant fanfare of the film’s opening. It feels like any order, any meaning or any patterns that have been found and conveyed, are all petering out, breaking up. In the Artforum interview, he says:

‘All my films are collage films, and I’ve wondered if [‘Painters Painting’] was one. And I wonder if there’s any relationship between what I was doing and the fact that I did know those painters who were doing collage before I ever made films.’

Out of all the mass of footage he shot, he’s made something where there are, as in collage, splices that really aren’t meant to be comfortable ones. There are, I think, shockingly abrupt juxtapositions and cancellations and overlays; and as the film moves towards its end, it’s as if the collage he’s thrown together is coming unstuck as we watch.

The look and feel of ‘Painters Painting’ are, in many places, pretty low-fi; the footage switches from colour to black and white and back again with no apparent logic- which leads me to suspect it might be a straightforward case of economics: colour film stock, back then, cost a bomb, and it’s perfectly plausible they ran out of cash halfway through, or that de Antonio knew right from the start he’d be filming on a shoestring, and rationed the colour stock accordingly…but I wonder, too, if all this drawing attention to the film’s making might be de Antonio flexing his creative muscles, as it were? As someone who moved freely around the social scene of the art world, creating without a brush, saying, in effect, ‘Look, everyone, I’m godlike too; I create’ in the same way as all these people he admired and was friends with. You know, he wants similar status for his film. And perhaps, too, he wants it to be as ultimately resistant to analysis as an abstract painting, by not adhering to the ‘rules’ of filmmaking, by not editing out things that shouldn’t be seen by the audience, or bothering to make sure that you can actually hear what’s going on without lots of echo and mumbling. It’s like he’s trying to be as authentic as the painters.

MD: Maybe that raw authenticity is its peculiar greatness, I don’t know. I find myself thinking, in certain places, is this just rubbish, chaos, a total mess? Or is it far more considered and clever than I’m giving it credit for? You know, I’m conflicted in my readings of it; but I think you’re absolutely right, we can’t get to the end of it. We can’t wrap it up and package it all off and say, right, that’s done with. That’s what’s so extraordinary about it. And I think we picked up on that from the very beginning of our conversation. It sets up a narrative, and then dismantles it. And the after-effects of experiencing that, for me at any rate, are a strange kind of dislocated feeling.

I don’t want to harp on about this too much. I think maybe I’ll try and make this my last word on it. There’s a blankness about Warhol and about Warhol’s work: there’s a hole at its heart, if you like. And I think ‘Painters Painting’ is, in some ways, de Antonio’s attempt to emulate Warhol’s blankness, and to have the viewer find in his film what they tend to find in Warhol: namely, whatever they’ve brought to it, their thoughts, emotions, preconceptions, reflected in the blank surface of the work. It’s possible to look into Warhol’s paintings and films and find sophistication and levels of meanings and narratives that you actually brought to the party yourself. Now, I wonder if we’re being steered towards doing something similar with ‘Painters Painting’? Is it just another dark, opaque surface in which we find ourselves reflected? All our hopes for and disappointments with painting, with how it all turned out?

6 thoughts on “Alan Gouk, Charley Peters, Matt Dennis: Fifty Years of ‘Painters Painting’”

Somewhat typically, Loveland reviewing the film, not the art. For me, sad to see the dealers stitching up the lucrative scene. Johns, Warhol, the most expensive Art Object at £900 Million. Like saying Trump should be President. Gross. Enjoyed Newman immensely, Poons, Olitski and Stella fascinating. Helen Frankenthaler and I became very close friends, talking together for months. She was a marvellous artist and human being, more than an equal on every level, a kind of grace under pressure. It’s hard not to see as defining.

I’m picking up on the opposition of “conflicted” versus “certain”. That’s the postmodernist’s dilemma. You can’t be conflicted and paint a convincing painting, only some kind of commentary on painting.

A great deal has happened in painting since 1971, especially in England. And it doesn’t in the least flow from Charley’s “with Pollock, the great prophet of painting-to-come, we have a kind of ‘year zero’ of painting, the absolute up-ending and rejection of all pictorial conventions”. (Greenberg’s whole enterprise is to counter such a notion). Or “Warhol […] delivered the coup de grace to a certain idea of painting”. Neither of these is true.

Nor is another commentator’s “Not since Jasper Johns’ final literalisation of the canvas surface has the meaning of a painting been looked for in its unmediated visual properties” ( or some such).

There has been a steady evolution, firstly out of Noland and Jack Bush, and Olitski and Poons, then away from them, picking up on threads of influence from the very painters the 1960s rejected. As always happens, the foreground preoccupations recede, or are an obstacle to up coming painters, and hints are picked up from the art pushed into the background. (And I don’t mean the RA’s “New Spirit in Painting”).

Hofmann and Still began to be seen as the most diverse and fertile sources, as opposed to the “one-shot” styles of the 1960s. And then came a reappraisal of Patrick Heron’s critique of the whole post-painterly phenomenon…and so on.

Charley begins by cavilling at the Creative Myth of Pollock, but later endorses it in the quote given above. Instead of looking for or declaring a year zero, as so many in the phony avant-garde have done, in order to erect an art theoretical paradigm shift, and declare the end of painting in favour of some “non- medium -specific” art, why not focus on the substantive formal characteristics of the paintings, their limitations and qualities? (Matt has a go at that with Noland). When you do, it becomes evident that Olitski is a glossed-over variant on Rothko. Noland, as Matt rightly suggests, is a variant on Newman. If Gottlieb was “pants- presser” to the Ab-Exers, then Noland must have ironed their shirts….. and so on.

My view, expressed in my book, that my generation are all children of Jackson Pollock somewhere along the line, reveals that we do not consider him the end of anything, nor as some mythic hero figure, but rather, that something in the impulses that he was “true” to in his best works resides in all of us if we can tap into it, and this has nothing to do with the specific facture of his paintings, which no one has been able to work out of, not even Helen Frankenthaler.

But Noland and Bush were still the most influential painters of the 1970s for quite a while in this country, even on the likes of middle generation artists like William Scott and Terry Frost.

Rather hoped Alan would come back with a response after his great show at Hampstead. The defining moment for me is when Olitski asks “what would happen if I extended the picture to 30 ft?” Alan and I took the trouble, as did Frank Bowling, to live transatlantically. I spent 15 years there, with Hartigan, with Ab-Exers, Guston, Tworkov, Ed Dugmore (Still’s closest ally). Then the years of the 1980s, with Frankenthaler, Poons, whilst working in construction in New York, visiting the Met on my day off, to see Easter Island Totems. I was spending time defining my view of what art was. I wasn’t cultivating galleries like Sean Scully. The testosterone was palpable at certain openings. I do wonder how young ambitious artists learn, when gender, ethnicity, all kinds of heavily weighted curatorial interference is so pervasive. In the library at Cheltenham Art School in 1967, I saw Newman’s “Stations of the Cross” as life-defining. I still do. It’s why the Brancaster Chronicles are so good, across gender and discipline, allowing us to talk about meaning and action with humour, and from various viewpoints. Careful you don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater!

I’d be surprised if Charley hasn’t read Mary Gabriel’s 2018 book ‘Ninth Street Women’, probably the best account of the origins and development of American abstract painting from the 1940s to the 60s. If so, I can’t understand her claim that Pollock was the end of something. For these women painters, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan, and Helen Frankenthaler, he was the beginning. And the reappraisal of their work has accelerated right up to today.

From what I’ve seen on Facebook, Instagram, can’t wait to see Noland at the Pace Gallery, which is on now. He couldn’t have been so close to Morris Louis and David Smith if he hadn’t made extraordinary works in the 1970s. I remember a show of the ‘Greyhound Bus’ pictures at Kasmins, which had echoes of Nicholson in Easy Rider. Irony? That went by the time I saw an Emmerich show with Olitski’s use of gel on the stripes, that was awful. That thing he did with his arms to judge orientation, limits, etc., is amazingly serious picture-making, which I agree has long gone, Hoyland and Gouk excepted on this side of the Atlantic. Stella’s ‘Protractor’ series, at 30 ft per shaped canvas, were special at the Hayward; Jack Bush’s rolled grounds at the Serpentine were so exciting. I could go on!…So glad I haven’t become so clever that the excitement of Real Art has been diminished one jot!