Alan Gouk: ‘Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, Part I: Open Conflicts, Hidden Affinities’

Instantloveland is delighted to present artist and writer Alan Gouk’s extended essay, ‘Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse’. In ‘Open Conflicts, Hidden Affinities’, the first of the essay’s two parts, he sees the volatile relationship between Gauguin and Van Gogh as a drama of influence and counter-influence, of shared and divergent intentions.

A curious lacuna of scholarship blighted the catalogue essays that accompanied the exhibition, ‘Gauguin: Maker of Myth’ at Tate Modern in 2011: namely, the total failure to take into consideration Nancy Mowll Mathews’ devastating, if speculative, critique ‘Paul Gauguin: An Erotic Life’, 1(Yale U.P. 2001) a forensic study that separates the myth from the life. Its rightful place was taken instead by a wrong-headed revisionism that put a positive spin on his charlatanism, giving succour to adherents of Postmodernist doctrine: making the artist, rather than the art, into the subject; ominously playing up to Gauguin’s ‘narrative manoeuvres’ and ‘overt plagiarism and recycling of ideas’; framing these, and ‘the appropriation of other cultures’ as the aspects of Gauguin’s art ‘that have the strongest appeal in the 21st century.’ Are all of these really positives?

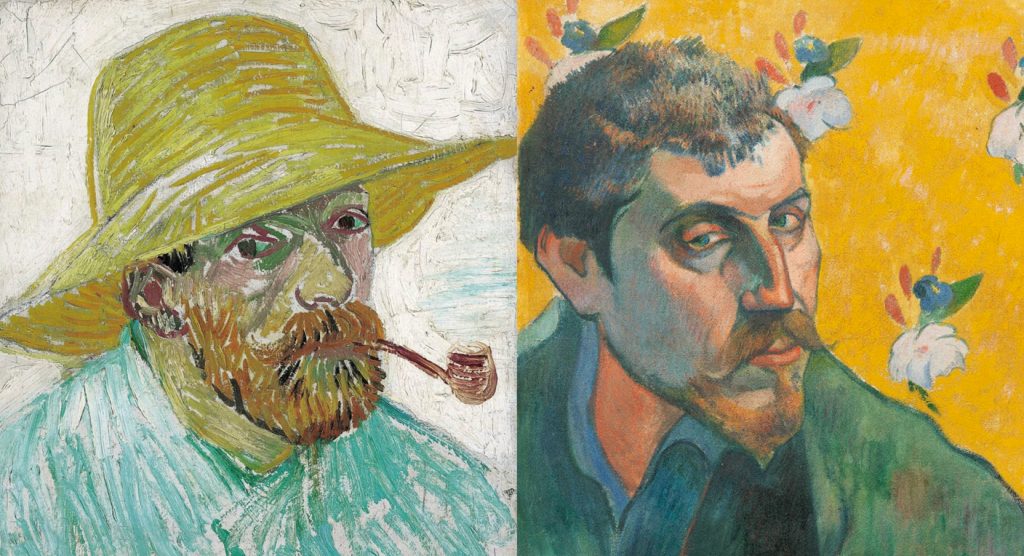

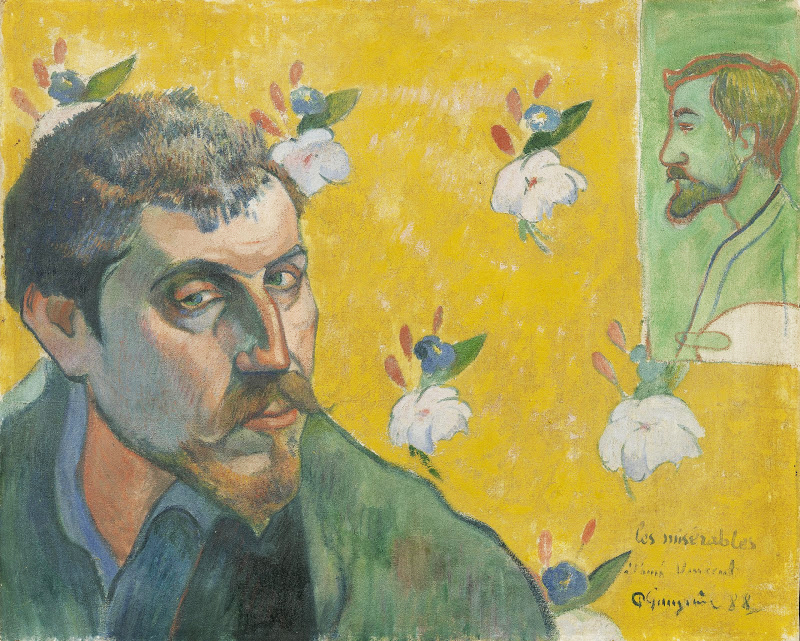

Much better is the scholarship in essays by Alastair Wright and Linda Goddard for the catalogue of the National Gallery’s current exhibition, ‘Gauguin Portraits’, that trace the literary sources which inspired Gauguin’s self-inventing personae, the laborious but brilliant transformation of his somewhat furtive and labile features into the hawkish caricature as ‘Peruvian’ ‘savage’. How hard he worked to achieve this identity, and how feeble in comparison are the self-promotional posturings of today’s aspirants.

However, there is no discussion by either Wright or Goddard of the intense arguments which raged between Gauguin and Van Gogh, influencing both artists reciprocally, during the former’s brief stay at Arles in the five or six weeks from October to December 1888, (so vividly portrayed in Vincente Minelli’s film, ‘Lust For Life’) ; unaccountably, since this intense period of mutual influencing, rivalry and recrimination is as seminal for the future development of modern painting as that which had taken place in the early 1870’s between Pissarro and Cezanne at Pontoise.

By October 1888, after two visits to Pont Aven, and the beginnings of a friendship with the young Emile Bernard, who was already close to Van Gogh and knew his mind, Gauguin had begun to formulate an aesthetic markedly different from the one he had imbibed from Pissarro and Degas. He could talk a good painting (or a revolutionary one); but at this stage he had shown little sign of the ability to paint one, with the controversial exception of ‘The Vision after the Sermon’ of September 1888, painted in response to ideas of Bernard’s, just before leaving for Arles; his motivation here being less to do with Vincent’s dreams of a camaraderie of souls, than to honour a financial contract mooted by Theo Van Gogh.

His Martinique landscape, painted the previous year on return to Paris, continued his habit of marrying Degas’ drawing style with Pissarro’s middle-period modelling of trees and hills through multiple overlaid feathery hatchings, predominantly green-in-green with contrasting areas of subdued orange-ochre. His ‘innovations’ at this date seem to consist of smuggling into the impressionist vocabulary not only storytelling anecdote, but also rejected and despised academic methods of quite conventionally-executed preparatory drawings, stressing contour, laid in piecemeal, without regard for their reciprocal influence, and infilling the silhouetted spaces between with relatively flat broken hatching of emphatically vertical or horizontal alignment.

This is not to say that his drawing, on both paper and canvas, is without original features; a distinctively Gauguinesque simplification of the line which designates the contours of a limb or the saliences of feature in his favoured black models is beginning to emerge, and a widening of the distance between figural contours, broadening the planes of their internal modelling to accomodate them to surface pattern, especially in ‘Among the Mangoes’ of 1887; but there is little evidence as yet of the new aesthetic propounded in his ‘Notes Synthetiques’ of ca.1888, a collection of professorial ex cathedra pronouncements which made him a hero of the young painters who gathered round him at Le Pouldu and Pont Aven.

Van Gogh was five years younger than Gauguin. Both began to paint relatively late in life; Van Gogh, aged 27 when he began, had only been painting for some eight years by the time he arrived in Arles. At 35, Gauguin had been painting for fifteen years, but Vincent had already arrived at a much surer grasp of the essentials of his own style, both in his drawing and consequently in his painting too.

When Vincent arrived in Paris in 1886, Gauguin had already been exhibiting with the Impressionists for four successive years, from 1879 to 1882, and again in the eighth and last Impressionist group in 1886; and yet within two years Vincent, through the originality of his drawing, artless, robust, chiselled, Hals-like, Flemish/Dutch in origin, (see ‘Four Cut Sunflowers, one upside down’ of 1887, in the Kroller-Muller Museum, Otterloo), and his admiration for Japanese prints, a vogue at the time, had arrived at a synthesis of Impressionist facture with a novel emphasis on flat pattern, bolder and more resolute than anything in Gauguin up to that point.

Emile Bernard, shortly to befriend Gauguin, describes Vincent thus: ‘Vehement in discourse…and such dreams, Ah! such dreams- giant exhibitions, philanthropic artists, communities, the foundation of colonies in the Midi…excessive in everything…enamoured of the art of the Japanese.’

The small ‘Self Portrait with Straw Hat and Pipe’ of 1888, in Amsterdam, whose simple power Matisse and Picasso emulated in their paintings of 1906, shows the extent to which Vincent had fused his astonishingly direct, chisel-like hatched drawing with form-creating colour. He was fast becoming one of the greatest draftsmen of 19th-century art. His portraits of self and others are greatly in advance of Gauguin’s at this stage, and would remain so.

Both he and Gauguin, in their landscapes, share the habits of conspicuous vertical and horizontal hatching derived from the Impressionists, especially Cezanne, but it is the boldness and variety of Van Gogh’s line-and-dot drawing that makes the difference. He had learned to create a subtle aerial perspective by the gradation of drawn lines and dots alone, regardless of colour, strongly reminiscent of Rembrandt and other 17th-century Dutch masters.

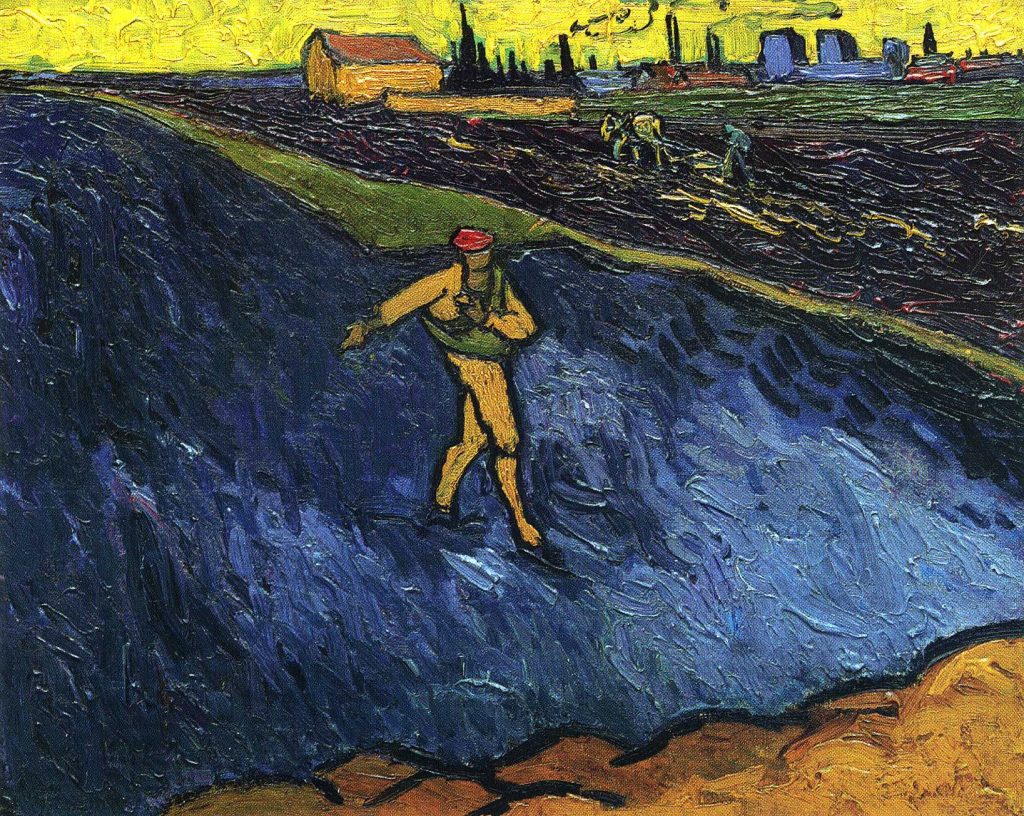

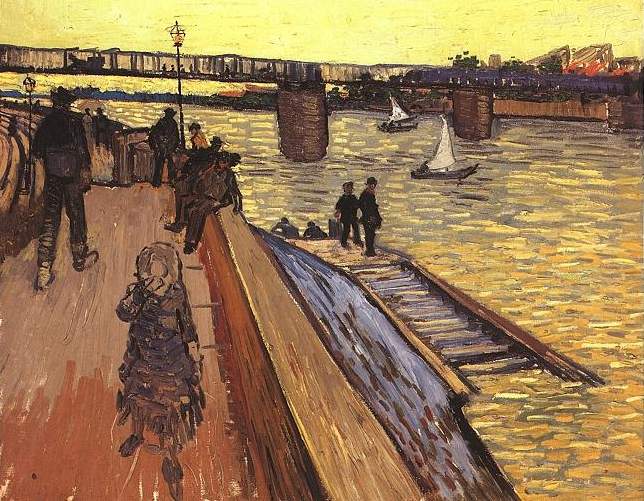

In ‘The Sower’ of 1888, in the Armand Hammer Museum, L.A., painted before Gauguin’s arrival, his colour is strikingly original, in places seeming unnatural, though no doubt in fact registering the strange lighting of an approaching twilight, as it does also in ‘Trinquetaille Bridge over the Rhône’ of 1888, where broad swathes of caramel and cocoa-coloured brushwork delineate the quay, and deep olive water hatched in with firm Monet-like strokes reflects a mustard- yellow sky, bridge and figures silhouetted in black; akin to Monet, but starker and more extreme.

Here, and in other paintings made at this time, Van Gogh has already acquired the impulse to stretch his colour, the better to express feeling (of course it does anyway, but here consciously)-‘something that is heartfelt and therefore sorrowful’ – through colour and line alone.

In all respects, in everything completed before Gauguin’s arrival, he is much bolder, his command broader, his means surer, less hesitant and equivocal than Gauguin. His colour is much richer, his handling more varied, his pictures more unified, more spontaneous, and as a consequence, they convey intention and feeling directly through their means, without obscurity. His written accounts, attempting to describe in words the myriad shades of colour he strives to notate, cover a wider range of descriptive words than any previous painter- ‘greyish pink’, ‘lilac’, ‘absinthe’, ‘malachite green’, ‘pale pink and apricot’, ‘yellowish white’, ‘russet gold’, ‘greenish bronze’.

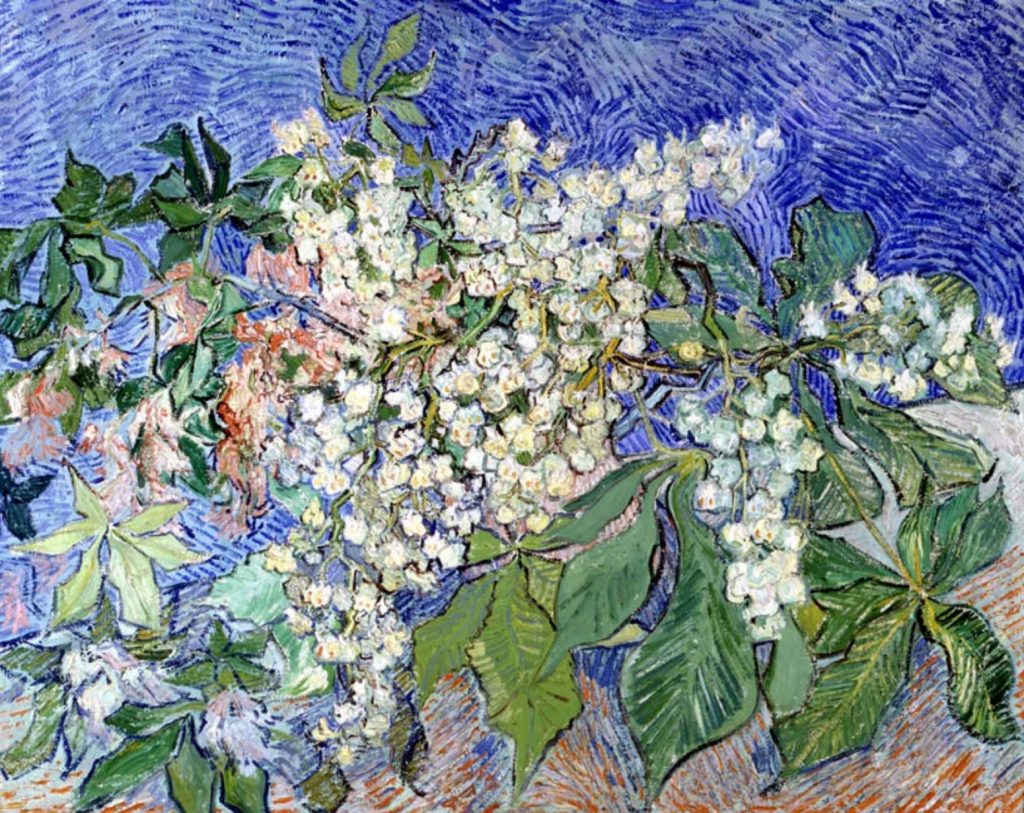

And one has to say, in view of the debâcle to come, that it is precisely because his engagement with the spectacle around him is so intense that his colour is so rich and inventive, bending divisionist practice towards realist ends, extending his palette into unforeseen regions in response to seasonal and weather changes, the coup de foudre of unusual light conditions amid blossoming trees and flowers.

In the ‘Trinquetaille Bridge over the Rhône’ his bold linear mapping-out of the scene is so sure that he can accommodate an extreme raking perspective to a vanishing point outside the left centre of the picture and a plunging transverse perspective beneath the bridge to the right-hand quarter, without compromising the dominant panel-like surface of the picture, unified by a predominantly sulphurous-yellow tonality with shadings of cool lime green and ochre shadows. And in ‘Madame Roulin and her Baby’ of 1888, he demonstrates complete mastery of the art of drawing a complex subject- a mother holding her baby in her foreshortened arms, hands exposed in foreground, her head in profile, the baby’s arms outstretched- without violating the flatness of the panel, a feat worthy of Rembrandt at his best.

After the precipitated crisis, and entry into the hospital at St. Remy, it becomes impossible to tell whether the turbulent, writhing, sea-sick rhythms which initially overbalance so many compositions are the result of pathological forces, or imaginative exultation, or both. But where Gauguin’s influence is in evidence, as in the wholly unnatural ectoplasmic whorling of clouds above landscapes conceived in a different mode, it is to the detriment of the pictures, introducing an aesthetic foreign to the dominant conception of the pictures as a whole (see ‘Landscape under a Stormy Sky’ of May 1888, in the Vaduz Liechtenstein Fondation Socindec.)

The diagonal tipping-up of planes, so that the terrain and buildings seem to be sliding downhill as in an avalanche or earthquake (as in ‘Field Enclosure [Mountainous landscape]’ of 1890, in Otterloo) is quite clearly a deliberate effect, based on a study, ‘Enclosed Field in the Rain’ of 1889, in the Philadelphia Museum, which appears to have been painted in situ, or from the window of the hospital. Van Gogh was perfectly conscious of the aesthetic effect of these vertiginous deformations.

Whereas Vincent’s fear of the bouts of religious exaltation which afflicted him after his incarceration led him to seek to calm his spirits (and painting seems to have been his only solace) by making copies after Delacroix’s ‘Pieta’, substituting his own features for those of Christ and thereby linking him to those earlier episodes in his life when he had felt the religious calling deeply, Gauguin’s portrayal of himself as a crucified Christ seems entirely bogus, prompted by self-dramatising. For Vincent religion was a torment and a consolation; for Gauguin (like Wagner, whose monstrous egotism, in all fairness, he does not come close to rivalling) an opportunity for self-aggrandisement.

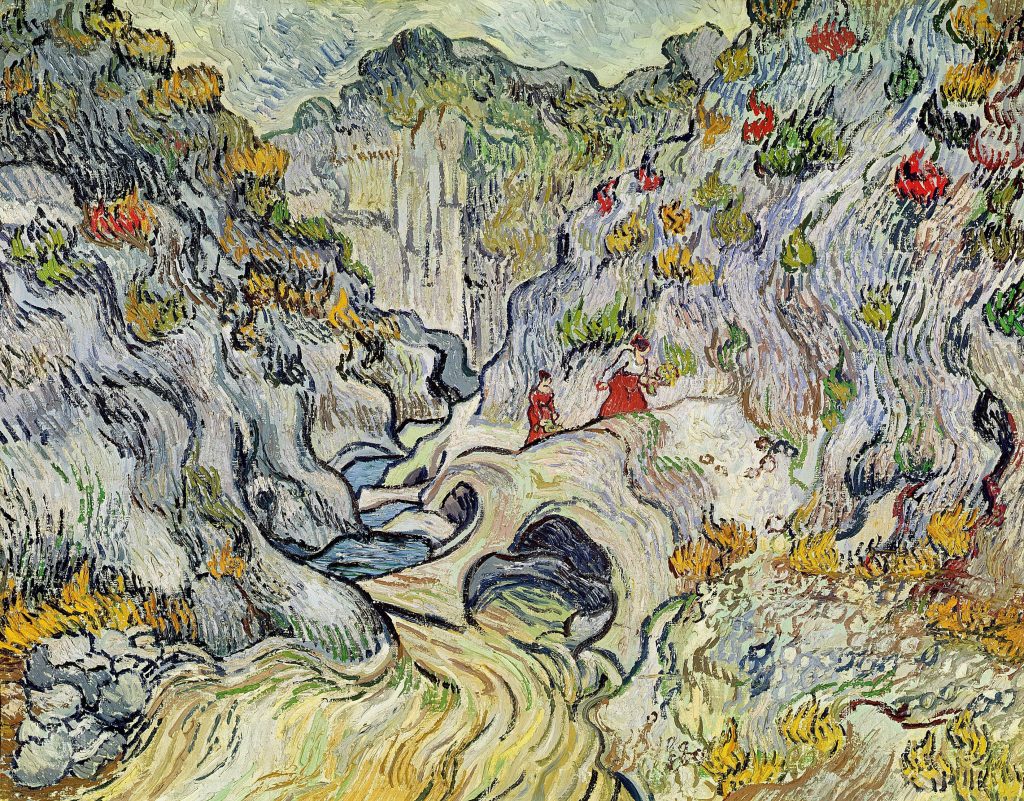

Whatever the causes, some of the St. Remy pictures exceed in richness, complexity and subtlety of colour anything Van Gogh had done before, or would do subsequently. In ‘Enclosed Wheatfield with Farmer carrying a Bundle of straw’ of 1889, in Indianapolis, the undulating passages of field and mountain have broken brushstrokes of a dizzying variety, of subtly related cool grey greens, shading to blues, olives and ochres applied in sustained rhythmic waves over the entire surface of the picture, unifying it through abundance. So too the ‘Path Through the Ravine’ of 1889, in Otterloo, one of his greatest pictures, and ‘Olive Orchard with a Man and Woman Picking Fruit’ of 1889, also in Otterloo, which exhibits an extraordinary variety within a narrow range of cobalt greens and turquoises laid against madder/orange tree trunks and shaded areas; and the marvellous ‘Blossoming Chestnut Branches’ of 1890, in the Buhrle Collection.

It is quite incredible that, despite the ravages of his mental illness, Van Gogh continued to urge an art which, like that of Claude Monet, delighted in the abundant vitality of the natural world, the rhythms of the seasons, the harvest, and man’s place within nature; a healthy art renewing itself by contact with the light of sun, sea, and sky. He deplored the elevation of arbitrary subjectivity in Gauguin and Bernard, and urged them to abandon a symbolism divorced from immersion in study of the natural world.

Modern painting, which really does begin with Cezanne and Manet, shows us truths about vision, namely that we do not see the phenomena of the world rationally or according to mathematical formulae à la Piera della Francesca (great though he is in his century). When we attempt to focus on an object, or one aspect of the visual field, the rest slips and slides away from focus, as subliminal presences, ghosts of perception; bringing a whole picture together on a flat surface necessarily involves a hierarchy of perspectives fighting for prominence, adjusted to one another, blurred, cursory, tentative; and in this sense, photography lies to us. Brushwork is spatial, but space is irrational. Any art in which theory precedes practice is a falsification of vision. When we are immersed in appreciation of the work of a great painter and turn to see the quotidian world, everything is mediated by that artist’s irrational vision. 2At a Matisse exhibition we turn to look at the crowd of onlookers; they all have beautifully symmetrically domed heads with Mediterranean almond-eyed beauty; when we are engaged with Nok, Ife and Benin sculptures, we turn round, and everyone looks like Sade, a beautiful African princess; when we are at a Picasso show we turn round, and everyone’s features are suddenly lop-sided; we see the efforts made to counteract the irregularity of facial features by plucking eyebrows, painting lips outside their natural contours, and other more contemporary strategies. When we turn around from Van Gogh, we see, with intense realism, the underlying spirit ablaze; and when we turn around from Gauguin, our gaze has become languorous, soporific, a dream projected onto reality, with moody, suspicious expressions, with that somewhat clichéd ‘sultry’ sexiness; but sexiness there is nonetheless. When we encounter any other human subject, depending on our temperament, there is an instant and inescapable erotic charge released between them and us, and a spiritual exchange (or as Mallarme would have it, a subconscious duality, both together, erotic and spiritual). ‘At all events, law and justice apart, a pretty woman is a living marvel, whereas a picture by a Da Vinci or Correggio only exists for other reasons’ [Van Gogh, to Theo, August 1888.] Of course we instantly suppress these feelings in ordinary discourse, but it is the artist’s task to bring them to the fore. Unless we are very cold fish, we do not see others as pieces of meat on stilts, to be rendered down in prosaic, pedestrian, affectless kitchen-sink dinginess.

While Van Gogh struggled to control his religious mania, Gauguin sought to exploit his own paranoia for careerist purposes, portraying the pair of them, but chiefly himself, as ‘victims of society who avenge ourselves by doing good.’ 3In a letter to Vincent, October 1888 No doubt hearing of Vincent’s pictures through the intermediacy of Emil Bernard or Theo, Gauguin’s ‘Christ on the Mount of Olives’ of 1889, is a triple expropriation, of Vincent’s Christ identification, of the olive trees Vincent would take up as his own symbol in challenge, and even of his red hair.

Gauguin’s symbolist leanings are theatrical, intellectual and literary, whereas Vincent’s expressionist tendencies spring directly from the intensity of the religious feelings which threatened to engulf him, and which he fought to subdue, when they arose in response to characteristics he was attempting to convey about his subjects, his sitters. There is really nothing ‘arbitrary’ about them. And they are already affecting his responses to his sitters before Gauguin’s arrival in Arles.

Vincent was more widely read than Gauguin, and yet the literary element in his painting is confined to the display of titles of books in his still lifes, and his admiration for Millet, which affects his choice of subjects. As early as October 1888, (before Gauguin’s arrival) he had written to Bernard ‘I have mercilessly destroyed one important canvas- a Christ with the Angel in Gesthemane- because the form had not been studied beforehand from the model, which is necessary in such cases.’

So then, of what did the sometimes ‘electric’ arguments between the two painters consist, since prior to their meeting they appear to have much in common? Van Gogh’s letters to Bernard and Theo show that he was already the ‘arbitrary colourist’, that he heightened his colour contrasts, anti-naturalistically within naturalism, for expressive purposes. Discussing his portrait of the artist Eugene Boch, he writes: ‘I intend to complete it as an arbitrary colourist, emphasising his fair hair, even to the point of using oranges, chromes, and pale citron-yellow. For the background I will paint a vision of infinity, a plain background of the richest, most intense blue I can contrive, and by placing his bright head against the deep background, I will give the effect of a star in the depths of an azure sky..’ 4In a letter to Theo of August 1888.

Both artists cite Delacroix as the source of their conception of the simultaneous contrast of colour (in opposition to the Impressionists’ use of warm and cool hues) and of colour’s musicality, and suggest that colour may create emotion in the same way as the music of Wagner (who was in vogue in France due to the influence of Baudelaire and the Symbolists); the link between Delacroix and Wagner having been made by Baudelaire in his criticism (and the attempt to draw analogies between music and colour going back at least as far as Poussin’s discussion of the varying ‘modes’ of his paintings.)

Gauguin had already been working on Vincent’s mind before arrival in Arles. In his letter to Vincent of September 1888, written just before his departure for Arles, he exaggerates the intensity and purity of his colours in ‘Vision After the Sermon’, in what is actually quite a sombre, muted picture, his colour not laid in alla prima, but layered and internally modelled, a practice he would continue all through his Tahitian works as well. (The solitary place this picture occupies in his oeuvre in itself suggests suggests an external influence, as Bernard would claim).

His description of his self-portrait (‘Les Miserables’ of October 1888) is aspirational and delusional, rather than factual: ‘The eyes, the mouth, the nose are like the flowers of a Persian carpet- also embodying the symbolist side. The colour is one sufficiently distant from nature; imagine a vague memory of my pots twisted in a grand feu firing. All the reds, the violets shot through with bursts of fire like a furnace radiating about the eyes- seat of the struggles of the painter’s thoughts.’ 5In a letter to Schuffeneker of October 1888 More accurately, Vincent writes to Theo: ‘It gives, above all, the impression of a prisoner. Not a face of gaiety…He must become once again the richer Gauguin of ‘The Negresses’…He seems to be sick, in his portrait, and tortured!! Wait, this won’t last, and it will be very interesting to compare this portrait with the one he will make of himself in six months time’ i.e., after the health-giving effects of life in the Midi.

Vincent painted rapidly, and stabbed in his ‘decorations’ with confidence, having often rehearsed with preliminary drawings in his Japanese/Flemish manner. Gauguin worked slowly, building up his cloissonniste zones of colour with several layers of near-glazes, close-toned shades of greens, blues or violets, with the hatched shading he had learnt from Pissarro (and Cezanne) still much in evidence. The transitions between surface pattern and the internal modelling which leads up to the contours of his figures are often tentative and irresolute (as is the junction between the arm holding a brush and the shoulder in ‘Portrait of Vincent Painting Sunflowers’ of 1888. He has not yet grasped the full implications of his developing style.

‘Gauguin liked to say that a work of art has to be entirely completed in the painter’s mind before he begins his canvas …. the artist would then jump to his brushes, and face to face with nature, in one sitting he would draw the poem out of his dream’. Written by an admirer long after the fact, this does not correspond at all with the evidence of the paintings. The conflicts between intuition and intellect, between emotion and theoretical promptings are played out in extended engagement on these and other canvases painted at Arles, and even more so on his return to Pont Aven the following year. Sensation, emotion, imagination, feeling, thought- the argument all boils down to their sequencing, the order in which they influence the painter’s inspiration, and the channels of assimilation which give rise to finished form.

Gauguin’s ‘Notes Synthetiques’ is astonishingly prescient of his later development, and written before he had entered the orbit of the Symbolist poets. ‘Art is an abstraction; derive this abstraction from nature while dreaming before it, and think more of the creation which will result than of nature’ (In a letter to Schuffeneker, 1888). Often in flagrant contradiction to interpretations put upon it by its Neo-Platonist advocates, ‘Notes’ anticipates so many of the convictions which would come to shape modern painting, (and a great deal of Matisse’s ‘Notes of a Painter’ of 1908), but none of it had been realised in Gauguin’s own painting up until October 1888.

He favours ‘intuition over reason’, and ‘thought over sensation’; yet he contradicts this with ‘How little power a reasoned sensation is (…) an idea can be formulated, but not so the sensation of the heart (…) And to say that thought is called spirit, whereas the instincts, the nerves and the heart are part of matter (…) What irony!’

He echoes the synaesthesic imagery, conflating the harmony of sounds with colour harmonies, which Baudelaire had imbibed from the German Romantic writers E.T.A. Hoffmann and Jean Paul, by way of experiences Baudelaire had heard of at ‘Le Club Des Hashishiens’.

Much later he would say, in ‘Diverses Choses’ of 1896, ‘One does not use colour to draw, but always to give the musical sensations which flow from itself, from its own nature, from its mysterious and enigmatic force.’

Though it would be anachronistic to impute these fully formulated opinions to the Gauguin who argued with Vincent at Arles in 1888, they nonetheless indicate clearly a point of difference. In an eloquent defense of ‘Where Do We Come From…?’ of 1899, he eschews the literary, allegorical approach to symbolism in favour of ‘animal figures, rigid as statues, with something indescribably solemn and religious in the rhythm of their poses, in their strange immobility. In eyes that dream, the troubled surface of an unfathomable enigma- it flows by implication from the lines, without colour or words; it is not a material structure.’

The words ‘obscure’, ‘incomprehensible’, ‘enigmatic’, recur. Gauguin has learnt the Symbolist lesson well. He does not, however, appear to have understood, or even attempted to understand the symbolic narratives he projected in his paintings. His attempts to specify their content, invariably written after the fact- sometimes long after the fact- are confused and incoherent.

‘Synthetism’ has both a formal motivation and a narrative parable-like story line, which when successful form a unified impression, but more often the two modes are at odds, causing lapses of taste, such as the habit of inserting explanatory incident, figures in the middle distance, which fill up an uneventful space in the picture, but are a jarring note of merely anecdotal curiosity (such as the male figure vaulting a wall in pursuit of two women in ‘The Yellow Christ’). Gauguin can also be prey to such lamentably literary symbolism as that practiced by Greuse, for whom ‘Weeping over the spilt milk jug, or the death of a pet bird …were symbols of the loss of virginity’ 6Henri Dorra, ‘The Symbolism of Paul Gauguin’, p 81. Of ‘The Grape Harvest’ of 1888, we are told that ‘the harvesting of the fruit symbolises pregnancy’, 7Dorra, ibid. Dorra asks: ‘Is Gauguin’s new insistence on the expression of emotion related to Vincent’s willingness to portray intense suffering (while in St. Remy)?’. He goes on to assert: ‘More than likely the influence of Vincent and of their common readings, Gauguin developed at this time, (Arles) a more profoundly humanitarian social philosophy, instilled with spiritual overtones, and he was quite conscious of this development.’ 8Dorra, ibid.

Although the catastrophe of their failed relationship had devastating consequences for Van Gogh’s two remaining years of life, (he died in 1890), Gauguin’s ‘Synthetist’ aesthetic theories had only marginal influence on Vincent’s paintings. ‘The Starry Night’ of 1889, for instance, showing Vincent’s ‘imagination’ at an extreme, had been planned a year earlier, and anticipated in the 1888 version in the Musee D’Orsay, Paris. Gauguin, on the other hand, was stunned into silence by the force of Vincent’s art, drank his paintings in while muttering criticisms, and was propelled by rivalry to feats of symbolist over-emphasis: ‘If they [the paintings Gauguin made shortly after arriving in Arles] are a bit gross, it is the hot sun of the south that puts us in heat, like animals’. His ‘Grape Harvest in Arles, or Human Misery’, painted in Arles in November 1888, is clearly a companion piece to Vincent’s ‘The Red Vineyard’, in which the human misery or drudgery is depicted directly, with no theatrical pointing-up, no head-in-hands sulking expression, of the kind Gauguin had copied from Vincent’s lithograph, ‘Sorrow’, executed six years earlier when Vincent was indeed subject to literary leanings.

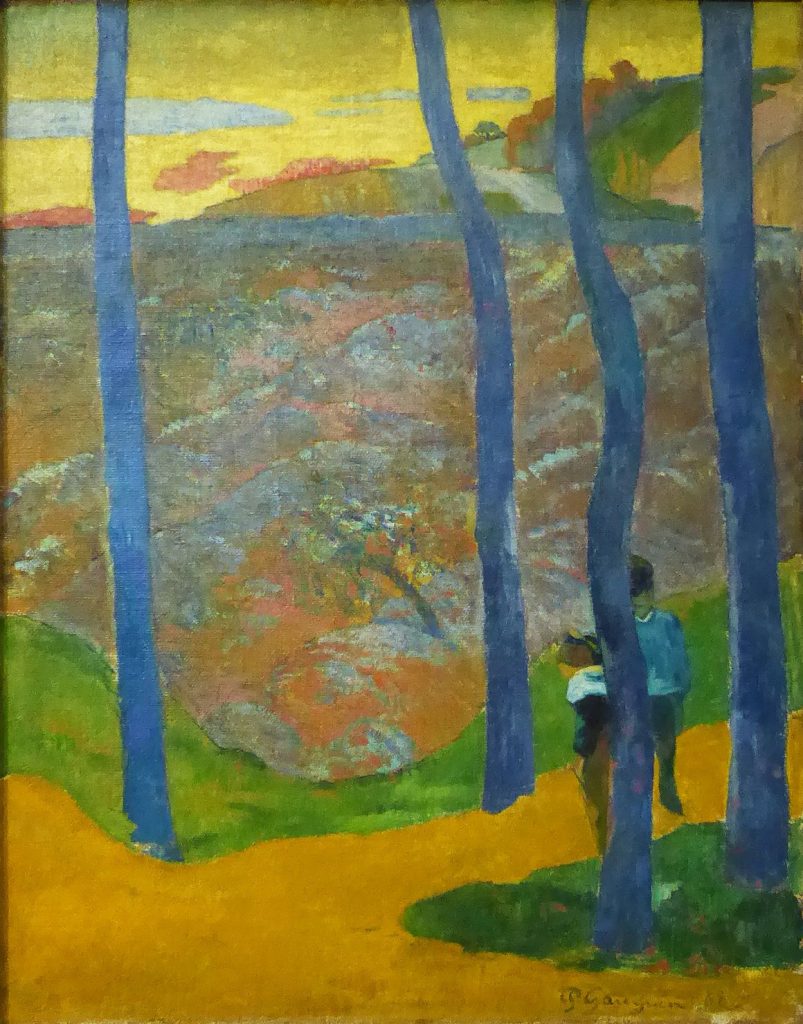

Gauguin’s influence is perhaps most in evidence in Vincent’s ‘Les Alyscamps, Avenue at Arles’ of 1888, in Otterloo, but Vincent’s ability to grasp the entire painted surface in a continuous act of bold, incisive drawing places it well ahead of any of Gauguin’s works up to that date, and his already burgeoning gifts as a colourist meant that in responding to Gauguin’s advocacy of imaginative symphonic colour-as -feeling, he surpasses him in producing a dominant chord of cobalt turquoise-green against orange-gold, giving, perhaps at Gauguin’s urging, the nap of the coarse grained canvas equal prominence across the surface in anticipation of a method Gauguin would favour in his Tahitian period. Gauguin’s much weaker version of ‘Les Alyscamps’, with a rhythmic array of verticals, would come in the shape of ‘Blue Trees (Vous y passerez, la belle )’ of 1888.

Even in the most obviously Gauguin-influenced ‘Memory of the Garden at Etten’ of 1888, Vincent does not stoop to the theatrics of sentimental symbolism which Gauguin injects into his parables. He has no need to; all the positives to be found in Gauguin’s aesthetic are already in play, and at full pitch, in Vincent’s art, without overstatement, without departing from ‘the possible and the true’; ‘Only here colour is to do everything and giving by its simplification a grander style to things, is to be suggestive here of rest, or of sleep in general. In a word, looking at the picture ought to rest the brain, or rather the imagination’ 9Of ‘The Bedroom’ of 1888, the first version, painted before Gauguin’s arrival, to decorate his room.

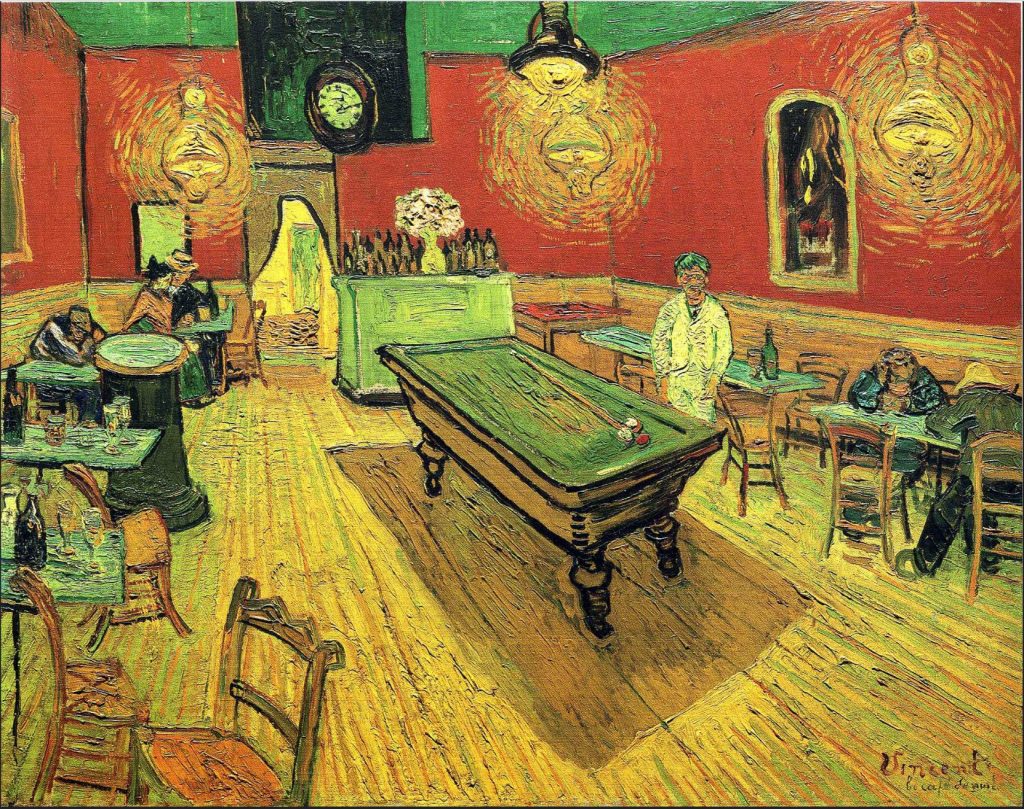

Here we have the main point of dispute between the two. Vincent does not want the picture to engage the viewer with abstruse speculation as to the ‘meaning’, symbolic or otherwise, of the configurations in the picture. He wants it all to be immediately legible, or rather, immediately felt and then later thought about, without giving rise to interpretative license foreign to the painter’s intention. Of the contrasting picture, ‘The Night Café’, he writes: ‘I have tried to express the terrible passions of humanity by means of red and green …. the powers of darkness in a low public house, by soft Louis XV green and malachite, contrasting with yellow-green and harsh blue-greens, in an atmosphere like a devil’s furnace, of pale sulphur, and all this within an appearance of Japanese gaiety and the good nature of Tartarin.’ In other words, no histrionics, no pointed-up plot, no stage-villain, gnomic ‘evil’, no downcast, shame-ridden sinners…

To be continued…

4 thoughts on “Alan Gouk: ‘Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, Part I: Open Conflicts, Hidden Affinities’”

Comments are closed.

I’ve so much enjoyed the descriptive details, the forensic analytical expositions and the clarity of thought, that run through this piece by Alan Gouk. It reinforces my prejudice or preference for art “history ” being more revealing to myself, when written by an artist. I was, only recently, confronted by a small exhibition of Alan’s work and was highly impressed ( in the best sense of the word) by it. In my opinion he is more akin to Vincent’s attitude, approach and work than to Paul Gauguin’s. I look forward to part two.

Terrific essay. Very welcome at this moment. Many thanks!

Really enjoyed this. Will re-read… Sam

As near as anyone gets these days to making great writing about painting.