Painter Tony Smith, Programme Leader in Fine Art at Liverpool Hope University, writes about the changing face of Liverpool, and the mercurial artist whose work did so much to shape his perception of it…

Liverpool, circa 1983: I had been playing drums in various post-Punk bands, working as a silkscreen printer and studying photography in the evenings with Stephen McCoy.

With a photographic project in mind, I and a fellow bandmate made a visit to the derelict Albert Dock. We climbed through a hole in the wall at the entrance of the long dockside west colonnade, finding our way into the huge warehouse, part of which had been designated for conversion into cosmopolitan apartments, gift shops and the new ‘Tate of the North’.

At this stage, the building’s insides were being ripped out in preparation for development, and I remember the site being full of pigeon droppings, dust, and broken glass. Through the smashed windows you could view the derelict dock, which had been allowed to silt up, shamefully neglected during Liverpool’s long decline from its heyday as a prosperous seaport. This was truly a bleak period: and so the news that the city’s long-neglected Albert Dock area was to be redeveloped came as a welcome glimmer of hope; on top of which, the prospect of a Tate Gallery opening on the site generated great excitement. Michael Heseltine had been put in place as ‘Minister for Merseyside’ and appeared to be an unlikely ally of the beleaguered city, if only in his defiance of the not-so-secret-plans of then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet for Liverpool’s ‘managed decline’.

We found our way up to the third floor, from where we could hear a team of builders on the level below; an encounter with this gang would have been likely to result in a rather one-sided conflict. Nevertheless, armed as we were with a Pentax single lens reflex and a roll of Tri-X film, documentation began….

There have been many memorable shows at Tate Liverpool since it opened in 1988; but the real eye-opener for me was Sigmar Polke’s 1995 exhibition, ‘Join the Dots’. This was Polke’s first retrospective, and his first major showing in the UK. I didn’t have much of an idea who he was; and with the internet then still in its infancy, I couldn’t Google him. The critical forum that accompanied the exhibition became a book, ‘Back to Post Modernity’ 1(Tate Gallery and Liverpool University Press, 1996). A year later I was to encounter this publication again when studying Fine Art at Liverpool School of Art under Roy Holt, who had contributed an interesting chapter to it.

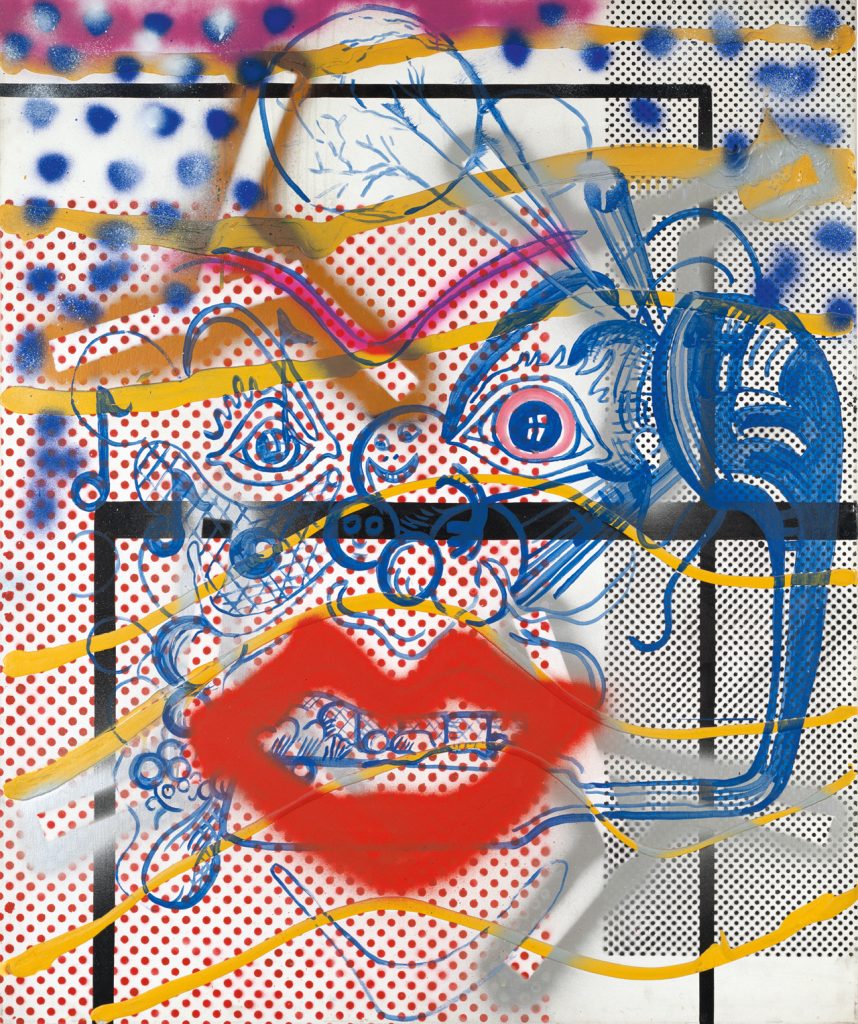

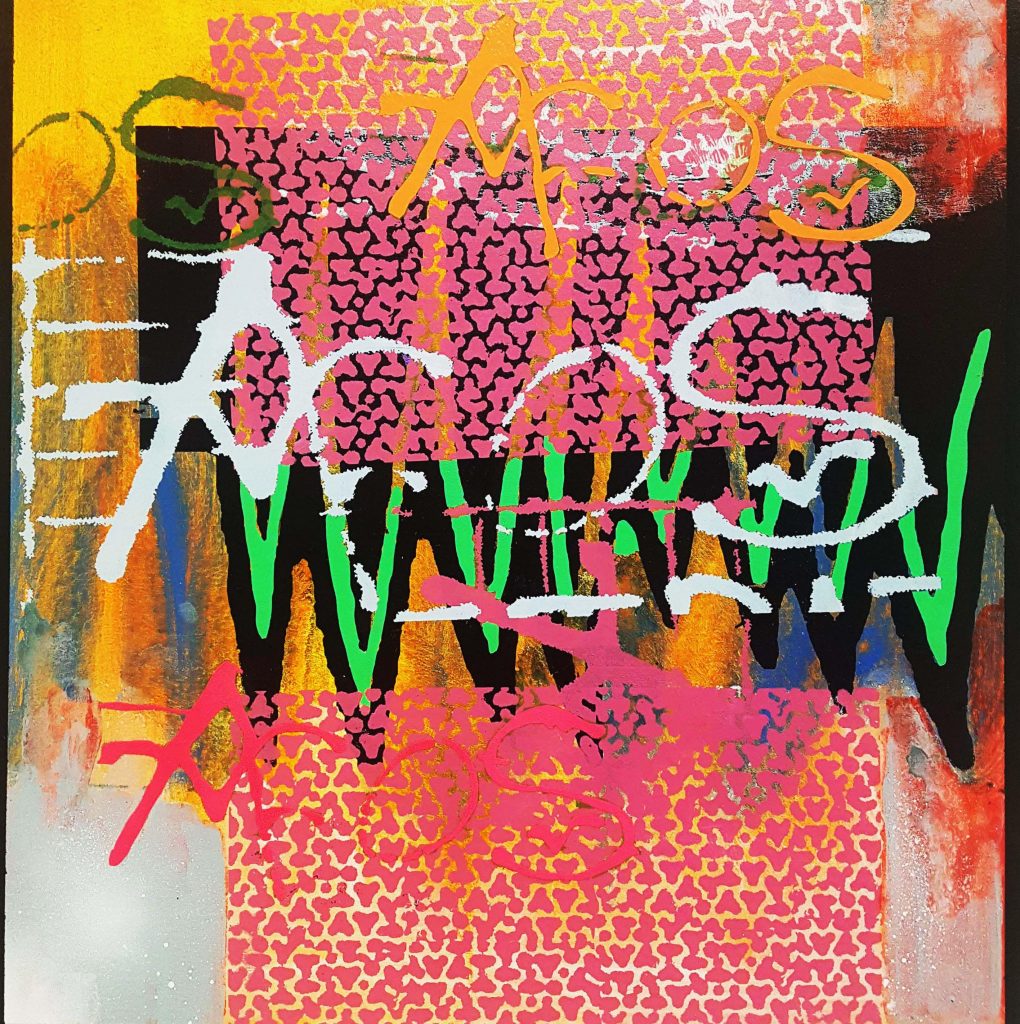

Almost every enthralling tutorial with Roy Holt would involve a reference to Polke. Holt’s chapter in the book, ‘Verbs Posing as Nouns’ described, in approving terms, Polke’s strategy of saying very little about his work. This reticence rendered Polke difficult to categorise or attach a label to. He shared the Dadaists’ attitude towards convention, but he could also be a Modernist, Anti-Modernist, Postmodernist, German Pop Artist, you name it. His allegiances were many, but never fixed. What impressed me deeply was his courage in mixing many differing signifiers with wild abandon, resulting in a nomadic aesthetic that both enticed and baffled the viewer. Despite their being pre-internet, Polke’s paintings anticipated our multi-image and information-drenched age. Polke’s grab-bag of samplings was open to interpretation, putting the viewer in the position of a detective when scrutinising his art.

As a student, Polke’s works were useful to me as examples of critical dialogue. One could see how he had plotted his way through Modernist and Postmodernist discourse, opening up -isms and movements to his wit, which carried a faint whiff of pejorative contempt. This, coupled with his ironic and intense critique of the practice of painting, employing a vast range of methodological subterfuge, was, and still is, fascinating to me. Amongst his complex interplay of differing stratagems and numerous dichotomous signifiers, I was particularly drawn to the perceptual oscillation achieved by his use of a raster dot system, which registers as an image from a distance, only to dissolve when you lean in for a closer look.

His methods were unorthodox, and his stylistic references subversive, kitsch, comedic, ironical and, above all, mischievous. In a single sample of Polke’s output, one could find oneself engaging with everything from Faust, Paganini, Max Ernst, Goya, and Blake, to German Romanticism and Warholian Pop. His whole oeuvre felt fuelled by a flagrant disregard for rules or conventions.

All this appealed to the student who had grown up in the era of Punk, witnessing Liverpool on the cusp of huge change; and who, showing a similar reluctance to follow rules, had sneaked into and photographed the derelict building that would one day be Tate Liverpool; a gallery where years hence he would find himself engaging with an artist’s work that, to this day, continues to change the way he thinks about painting. There’s something very Polke about that. Joining the dots….