Matt Dennis on ‘The Shape of Sound’: Noela James Bewry and Alexandra Harley at Adderbank Gallery

Over the past decade, Noela James Bewry has been developing an abstract painterly language of extraordinary richness and power. The fundamental building blocks of this language have been, till recently, brushstrokes of uniform width, forcefully applied, forming armatures of paint that zig-zag and backtrack and bend back on themselves, spelling out an abstract alphabet that crowds out the paintings’ shallow space from edge to edge in tangles of prismatic colour; more often than not laid in with a brush loaded with both coloured and white pigment that puts the paintstrokes down streaked with highlights, wet into wet, layer by layer, bathing the interlocking, jostling forms in silvery, slithery light.

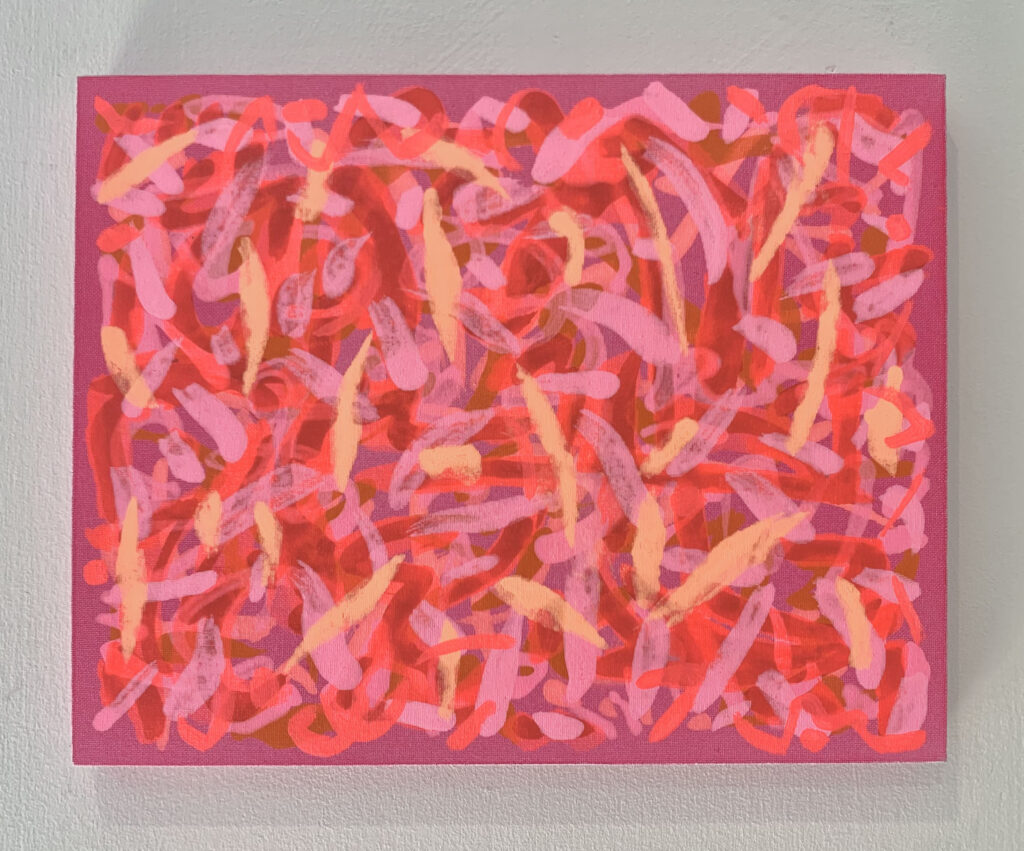

Now, as this selection of paintings from her recent ‘Soundscapes’ and ‘Sound Walls’ series shows, the sumptuous painterliness and frenetic rhythms have been reconfigured, the brushstrokes thinned to a looping calligraphy that flows more from the wrist than the arm, and the colour calmed and codified into the sparser, interwoven fields of a pictorial decorum that feels new to Bewry’s art.

The new paintings have evolved out of the artist’s concentrated engagement with music: the process begins with countless quick notations made in pencil, charcoal or crayon on sketchbook pages whilst listening to ambient or minimal works, such as Philip Glass’s ‘Koyaanisqatsi’, a suite of pieces written to accompany Godfrey Reggio’s astonishing documentary, put together from sped-up footage of American city life. Here, music that finds its point of departure in the visual realm is brought back to that realm by the action of the pencil or the brush, not through the creation of a recognisable image, but by a layering of countless flourishes and traceries that build into dense textures that seem to flicker and pulse in a manner analogous to the composer’s insistent rhythms. In the paintings that pre-date the ‘Shape of Sound’ works, the thick, polychromatic knots and tangles of brushstrokes appeared to continue beyond the edges of the canvas, thereby rendering it, despite its assertive physical presence, as a view of an ‘elsewhere’ seen through a rectangular portal; by contrast, in the ‘Baracoco’ and ‘Small Sound Wall’ paintings, the thickets of marks appear to self-generate in an expansive movement from the centre outwards that stops short of the edges on all four sides, a formal device which serves in each case to locate the image in the ‘here’ of the canvas and nowhere else, complete, fully present, contained, yet lacking any sense of beginning or ending; again, a thing seen that works by analogy to offer an experience that somehow runs in parallel to that offered by listening to music, of grounding us in its ineffable here and now, in the midst of surrounding silence.

Figurative art is of no use here; it points away from itself, at something else. Only abstract art can make this kind of attempt, because, like music, it is the thing in itself, self-revealing, self-referring, self-sufficient. Like music, it does not represent; it presents.

These paintings seem to give visual form to TS Eliot’s marvellous description, in his ‘Four Quartets’, of that endlessly-sought, yet rarely found experience of total identification, on the part of the listener, with that which is being listened to:

‘You are the music while the music lasts.’

Alexandra Harley comes out of a generation of abstract sculptors whose evolution has, in most cases, moved along pathways towards an ever more intensive preoccupation with forms of all-overness, in which a great many small components are joined together in endlessly varied articulations and constellations, weaving a net to catch and hold their internal spaces. She stands somewhat to the side of these developments. True, her work is very much concerned with part-to-part articulations within a sculptural form; but where she parts company from many of her contemporaries is in her concern with bold and blatant contrasts, with juxtaposing two or perhaps three distinct elements- formally, or materially, utterly unlike each other- and daring them to find a way towards resolution: for her, a sense, suddenly apparent, of what she has described as an ‘internal cohesion that asserts itself as rightness.‘

Watching Harley unpack her small sculptures and begin the work of placing them on shelves and plinths in the bright, intimate space of the Adderbank Gallery, what came across with unmissable force was the level of serious playfulness at work: the playfulness evident in the extent to which she is willing- and very, very able- to bend and stretch the set of conventions for abstract work in three dimensions that her generation have inherited, and the seriousness making itself felt in her refusal to let that playfulness curdle into the kind of knowing kitschiness that so often seems to go hand-in-hand with the manipulation of the kinds of ‘real-world’ materials that she frequently favours.

One might see her philosophy as one of ‘whatever works’; and if that means a little bit of fooling the eye, well, fair enough. Unquestioning loyalty to ‘truth to materials’ when fabricating ‘Nep’, ‘Lledr’ and ‘Juba’ would have compelled her to keep what she described as the ‘uninspiring surface’ of the coils and rolls of fired clay in its natural state; instead, the applied paint seems to work like alchemy, having us feel that we’re dealing with a material never encountered before, and that if we were to cut into the works’ substance, we would find that the orange, green or blue runs all the way through. And even when we’re not fooled, as in the case of ‘Billig’, where we know very well that there are branches and twigs beneath the work’s unifying skin of Cadmium red, we’re left with the delicious double shock of spikiness and sensuality arriving at once.

‘Coe’, ‘Cleaf’, and ‘Korapiloa’ all make use of bronze, but sparingly so, and in ways that feel intended to undercut its aspirations to exalted status. The sense of a hierarchy of materials, with bronze on the top tier, is entirely absent: it’s just one more kind of thing to be played off against another kind of thing; no standing on its dignity here. The bronze filaments in ‘Coe’ are unlovely, gawky, utterly lacking in poise as they emerge, bedraggled, from the aperture in the stone; the bronze ‘climber’ in ‘Cleaf’ clings to the standing slate for dear life; and the twin patinated forms in ‘Korapiloa’ are caught up inside a snare of coiling wire.

In the hands of a lesser artist than Harley, these intimations that the works carry, of precariousness, of momentary equilibrium teetering on the brink, of order barely maintained through quick-thinking improvisation, would topple over into a sentimental kind of sculptural illustration. Her grounding in a discipline of pure form, and in the late-modernist tradition that still held sway during her years as a student of sculpture, acts as a bulwark against narrative and the use of symbols. For Harley, the work is not finished until it has been ‘divested of all resemblance’; often, with that goal in mind, she will turn off the lights in her studio just as darkness is falling, the better to view the work as pure silhouette, deprived of surface detail, and to understand what still might need to be done to distil it down to its essence. The coils of clay, the cut and stapled lengths of branch, the shards of slate, the cable ties, all of the heterogeneous materials she employs, are themselves and nothing but. The poetry in her work is found at the point where these materials meet.

‘The Shape of Sound’ can be viewed at Adderbank Gallery, 132a Bisley Rd, Stroud, on Saturday June 21st and Sunday June 22nd, between 11am and 5pm.

This article is a revised and slightly enlarged version of a short text commissioned by the artists to accompany the exhibition.

2 thoughts on “Matt Dennis on ‘The Shape of Sound’: Noela James Bewry and Alexandra Harley at Adderbank Gallery”

It is good to read Matt Dennis again after such a long and unexplained absence.

Your prose and style have been an example of how writing about art should read.

Alas, I am unable to get to Stroud to see ‘The Shape of Sound’, and will not make a comment from reproductions, but break that rule after my eye was arrested by ‘Korapiloa’ by Alexandra Harley. A sculpture that seems inspired but different from her others. It reminds me of Claire Finkelstein, the Californian sculptor, and her work in copper and glass. Not rated in the UK, though exhibited in Margate alongside fellow Californian women, (and badly at that.)

Harley’s piece uses literal differences to superb effect, the bronze ribbons floating in the copper wire mesh. It’s new and I look forward to seeing other sculptures of this standard.

Many thanks for your kind words David. I shall keep you posted!