Matt Dennis in conversation with Ian McKeever: Pt 1: ‘Presence and Absence’

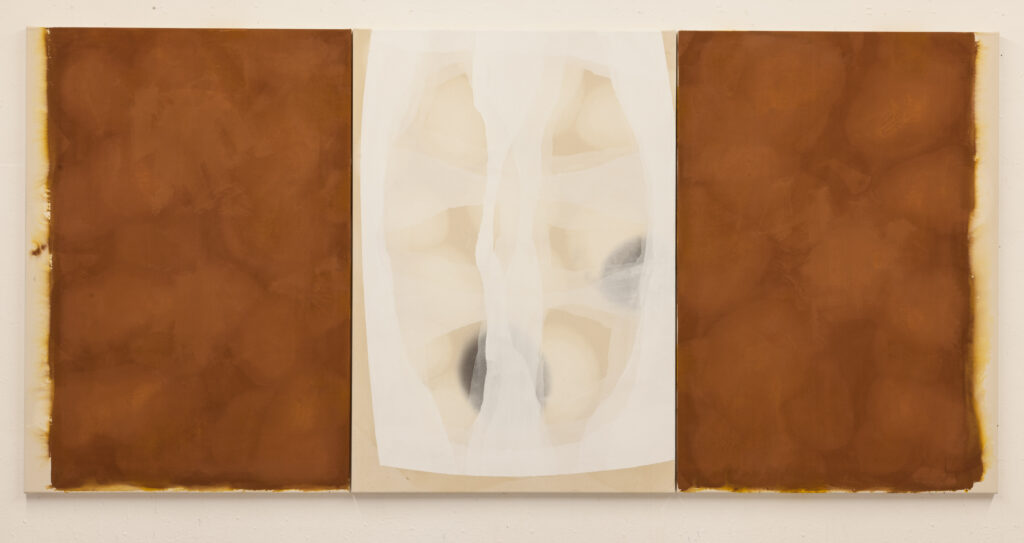

The paintings of Ian McKeever are unlike any others being made now. They are abstract, but appear to owe no debt to any of the known lineages of abstraction. The material characteristics of their constituent parts- single-colour panels worked by the slow laying-down and layering of paint – overlap with those of monochrome painting; yet the sense of ineffable, intangible presences generated by their grouping together into the artist’s favoured format, the diptych, situates them very far indeed from the reductiveness of minimalism, and from its demand that paintings be understood as the deployed presence of paint and nothing else.

‘Presence and Absence’ is the first part of a transcribed interview conducted over the spring and summer of 2023 in McKeever’s Dorset studio. Starting with the three large paintings from the recent ‘Henge’ series hanging on the painting wall, and coming back to them repeatedly across hours of recording, the conversation moves back and forth between McKeever’s beginnings as a painter during the heyday of conceptualism; his subsequent long involvement with work made in and from the landscape on his extensive travels, in which photographic grounds were overlaid by gestural paintmarks; and his development over the last three decades of a singular, inimitable painting practice, in which thinned pigment is applied in translucent veils that hold within their layering the months and sometimes years that have gone into the works’ making.

Working always in series, the paintings’ sizes, formats and pairings of colours are established beforehand; yet, as McKeever has explained, these decisions are not intended to ‘pre-empt what the painting might be, or limit it, or lay down preconditions for it’, but to mark out territory. Within this territory, over the course of a long engagement between the artist, the material, and the canvas surface, during which months may pass without a single stroke of paint being applied, the work manifests itself, dark and radiant; resistant to any attempt at explanation or interpretation, but inviting- and rewarding handsomely- a slow, patient act of seeing.

MD Looking at these three paintings from the ‘Henge’ series hanging here, I think I’m just starting to feel my way into an understanding of your concern with what you’ve called ‘the time of painting’– which I take to mean both the time taken to execute the work, and the sense of time it bodies forth; and of course how the one connects with the other. These ‘Henges’ feel glacially still: and as I think back to earlier bodies of your work, I sense a progressive ‘slowing down’, from the scribbled pencil hatchings of the ‘Fields’, through the gestural brushwork of the ‘Traditional Landscapes’ and ‘Lapland Paintings’, the pourings and stainings in the ‘Diptychs’, the floating ectoplasms in the paintings from the ‘Hartgrove’ paintings and beyond…

IM Perhaps I understand this slowing down as becoming more measured, more reflective in my approach to the work. Certainly the immediacy of, say, the works from the 1970s and 1980s has gone out of the work, but my concerns then were very different. What one might call the immediacy of the landscape and its equivalent in painting, how the two as processes overlapped and collided has, over the years, given way to a more reflective approach. I don’t think I’m out there anymore.

MD I understand. With your landscape works, with the works derived from photos taken and sketches made in the landscape, you were undertaking physically arduous treks to gather your material, weren’t you? You were on the move, putting up and taking down a tent, walking long distances, clambering over rocks and obstacles; so there was an implicit kinetic element. You were passing through landscape.

IM I think I was. I wanted the works to reflect that immersion. I still travel, but I no longer make those long, arduous journeys to, say, Papua New Guinea or Siberia. My travelling now is more culture-based, and deals with mental space, and has different constructs to it; a different sense of time, and of place. Over the years, I’ve tried to take the heat out of painting. Temperamentally, I’m someone with a hot side and a cool side, and I’m often torn between the two. Within a group of paintings, I can sense those that are, shall we say, heating up more, and those that are cooling down. Increasingly, the way I work is to try to take the heat out of the painting, to pull the painting back to a sort of steady state.

MD That’s a very interesting description, because one can see how a desire to reduce painting’s heat could relate to a desire to reduce movement to stillness; after all, if I’m remembering my physics, at the atomic level heat is simply agitated movement… in the ‘Henges’, I take this idea of removing painting’s heat to be as much to do with eradicating any sense of frenetic busyness, as it is with emotional heat?

IM On one level, it’s to do with gestural mark-making and the frantic energy that relates to so much painting, especially abstract painting. With moving as far away as possible from all of that, from the gesture which becomes a signature, as in, say, De Kooning or Emilio Vedova. Most painting that deals with gesture doesn’t have that tightness, that autonomy that I look for, it’s just mark-making. And I find mark-making for the sake of mark-making gratuitous. So over the years I’ve tried to develop a language which moves away from it: still organic, still fluid, still open to the vagaries of the act of working with paint- but one which isn’t displaying that distinct, manifest action of the arm passing through the air. The painting has to be held where it feels alive to the touch, yet has a stability, a stillness to it.

I’m looking for a painting that is immutable, but at the same time furtive; a kind of painting that is on the one hand as solid as rock, but on the other hand light as air: as transparent, as furtive and febrile as air.

MD Certainly, if you don’t record a gesture when you paint, then that offers up a different reading of the painting- the painting is more phenomenon than record of action. The ‘Assembly’ paintings, for example, even when you’ve clearly mixed thinned white acrylic paint and laid it down onto the canvas from a bucket, presumably, or a mixing bowl, there’s no emphasis on the kinetic action of a splash; they look more like efflorescences of mineral salts on stone walls to me, like a phenomenon that’s bloomed with astonishing slowness, and one where there is no agency involved in its appearance. To my mind, it’s the sense of agency in your paintings that’s been reduced and reduced, and with these paintings in front of us, whilst I know intellectually that an artist’s hand made them, the material feels not manipulated, but simply manifested, if that makes sense.

IM Yes, all of what you’re describing. The ‘Henge’ paintings- in total, ten large ones, eight medium-sized, and ten smaller ones- I’ve worked on them for five years, so they come through very slowly. I work in the studio most days, but I don’t churn paintings out, I don’t paint paintings quickly. For instance, if I’m working on a painting and it’s going well, then at a certain point I will stop working on it; I don’t want the heat to build up in it, and I will put it aside and only come back to it two months later, or even six months later. From the initial stretching-up of the canvas, to the point at which I think the painting is finished, there may be two years during which I’m intermittently working on it.

MD It’s a point of principle for you, that the painting must evolve slowly?

IM Yes.

MD So if you came in here on Tuesday afternoon, started on a fresh canvas, and by teatime you had a painting, you wouldn’t believe in that painting, so to speak?

IM I wouldn’t trust such a painting. Even in the smaller ones, time is crucial for me, far more, I think, than notions of space; there must be embedded, cumulative time in a painting. The idea of starting a painting at lunchtime and being finished by the evening has no appeal for me, no interest. I need to feel that the time in a painting has accumulated over time, has found its way into the painting. I’m a great believer in painting on paintings when you’re not painting on them, that you start a painting and then work on it for maybe a few days, and then put it aside and don’t touch it for six months.

Those six months are nevertheless in the painting, and when you go back to work on it, you haven’t gone back to five days’ worth of work already done, you’ve gone back to six months and five days worth; this gives the painting another kind of time. There’s an accretion going on; I have to be able to feel that this is evident in the painting. One week you might be feeling buoyant and energised, and the next far more melancholy, or what have you; and so it’s important that the painting doesn’t hold simply one mood within it. It has a multiplicity of moods, of experiences, passing through it, during these different phases, that are you, rather than the painting only embodying one aspect of you.

MD But there’s also the attempt to efface any trace of what we might understand as expressionism, any trace of your feelings? A feeling in the moment, an angry feeling, a vexatious one, a euphoric one, is of no interest to you as a something to manifest in the work in an obvious sense? If someone was to say to you, that looks like an angry painting, then you’d consider that painting a failure?

IM I would. And there’s the other side of the coin: you work on a painting, and you decide it’s finished, and you say, today I declare that painting finished; but on that day you have to go for a three o’clock dental appointment, and so whenever you look at that painting subsequently, you’re going to say, that’s the painting I finished on the day of a toothache. I can’t work like that. I don’t want that level of autobiography in the work. I stop work on a painting, I put it aside, I bring it out again; I may sit with the painting for a week and do absolutely nothing other than look at it day after day and try to figure out if I should go further with it. If I can, then I will; and if not, I may say, well, I don’t know what to do with it, and I’ll put it away again. This may go on for a year. And at some point, I may say, okay, then it must be finished. But I couldn’t tell you what day that is. When I’ve finished a series of works, I may get asked, which was the first one, and which was the last one? The question is quite meaningless to me; they’ve all been made simultaneously, and what has come out first, and what has come out last, doesn’t really have any meaning. I number them sequentially. People often assume this ordering is chronological; it isn’t. It’s simply a means of identification.

MD So none of a group of works will see the light of day, in terms of being exhibited, until the whole group is fully resolved?

IM Yes. I have a guiding principle of not working towards deadlines; I make a body of work, and when it’s finished, I say, okay, now these could be exhibited.

MD Does that make you a gallerist’s nightmare?

IM Yes (laughter). Most of the galleries I have worked with for many years, they are used to my rhythm and my way of working. I need long periods of focus in which to develop a group of works, with all the works present in the studio.

MD The phrase ‘a body of work’ has great resonance for you, doesn’t it? That the work will be seen as a body, in its entirety, with the understanding that this series, this group, coheres.

IM I prefer to make solo exhibitions, and show one group or body of works. A greater resonance comes through, and a sense of the evolution of time we’ve spoken about. That sense of setting up a total feel through all the work is very important to me. Single paintings: of course they’re valid, and they stand on their own; but seeing them collectively establishes a different level of resonance, which I enjoy very much.

MD I wonder if this sense of the importance of the collective effect of a group of paintings became stronger for you with your series, ‘The History of Rocks’? It’s been described as a forty-part single painting…

IM It’s an interesting group, in that I set out in 1986 to paint individual paintings, all of them 145 by 106 cms. I realised, once I was fifteen or so paintings in, that they simply constituted one collective work. In the end, I made forty, as it was going to be my fortieth birthday. It was also the year that my younger sister died, so there were a lot of reverberations and associations for me. I wanted to keep all the paintings together, to gather these associations in one place, as it were; but by the time I arrived at this realisation, I’d already sold one of them. So I bought it back, and put it back into the group-

MD Without too much resistance from the person who’d bought it?

IM Well, the collector didn’t want to sell; but he understood what I was trying to do, so reluctantly agreed to. I showed the whole group for the first time at theKunstforum, Lenbachhaus, Munich and about a year later they went to a private gallery in Zurich. It was agreed that they’d all be kept together as a group, and only sold as such; and of course it was a very difficult piece to sell, it was huge. Unbeknownst to me, though, the Gallery owner started selling them off individually-

MD Whoops-a-daisy…

IM And the work was fragmented into forty separate panels that were sold to different people.

MD I’d simply assumed that the whole installation had been bought by the Morat Institut, Freiburg…

IM They had wanted to buy it. But when I got around to discussing it with the Gallerist, he told me he no longer had the whole group, he’d sold some of them, which came as a complete surprise to me. Things quickly went downhill from there, leading to a lengthy legal battle. The Swiss legal system is, to say the least, difficult to navigate and expensive. After three years of basically getting nowhere and not knowing who owned the individual panels, we threw in the towel. For me, the work is no longer a viable part of my oeuvre; that is, unless and until all 40 panels are reunited as one work.

The whole thing was a very painful experience, on many levels.

MD Since then, you haven’t done anything comparable; the work emerges in series, but there’s no intention on your part that it stay together, all owned by one collector…although that would be the ideal, I suppose.

IM (Laughter) It would. But you’re right, subsequent to that, I’ve worked in series, but I’ve never felt that all the works should remain together. With the series ‘Twelve Standing’– twelve paintings in total- I’ve shown eight of them together, six of them together, but the entire group of twelve only once, at the Ferens Gallery in Hull, where they had the perfect space to show them all. This is increasingly the situation, that it’s not been necessary for a whole group to be shown, as long as I feel some corpus of that greater body is present.

MD Because there are dialogues going on within the groups of works, aren’t there? I was looking through the catalogue of the ‘Henge’ paintings and noticing instances of ‘theme and variations’, where three or four of the works will attack the problems you’ve set yourself in a similar manner, and so will cohere as a sub-set of the whole. And these three we’ve been looking at here, on your painting wall; are they together by chance, or because you feel they belong together?

IM No, I put these three up because they’re the only large ones from the series I still have here; five of the group went to Copenhagen, and two to America some months ago. And of these three here, each of them represents one of the sub-sets within the series as a whole.

MD Let’s talk about them. Thinking about the varying sizes of the paintings within the ‘Henge’ series, I’m curious to know what governs your decision-making as you feel your way into the formats you’ve used?

IM The large ones, which are 240 by 285 centimetres, I intend to have real visual and physical presence: for me, there’s certainly a limit as far as how big I can make the painting without feeling as if I’m losing it. This size felt right to me. If you think about how I was painting fifteen or twenty years ago, with the ‘Temple’ paintings- three metres by four and a half- then, I could physically lift a painting of that size; I can’t do that anymore.

Quite recently, I was in Paris, and I saw the Joan Mitchell exhibition at the Vuitton Foundation. I knew her and visited her and we kept up an occasional correspondence. I was curious, because the last time I saw Joan Mitchell was in the late 1980s- she died a few years later- Gerlinde, my wife, and I were in the studio with her, and she’d painted these paintings that she showed to us in loose configurations. I sensed quite strongly that the final decision for each configuration of say three or four panels together constituting one larger work was still to some extent open and that she was still shuffling the pack, so to speak. Her polyptychs often have the feel of surprise encounters from section to section. I don’t have that kind of latitude or fluidity, In the Henge Paintings A goes with B, I can’t suddenly change B for C.

Coming back to this notion of size: if a painting gets too big for me, it just becomes yardage, and I lose control of it. Alongside the larger ‘Henge’ paintings, there is a group of middle-sized works in the series, at 180 by 215 centimetres; and I still feel at that size the painting retains its physicality, its presence on the wall. Subsequent to them, I also painted some smaller pieces, at 125 by 145 centimetres. They’re curious, and they allowed me to see formal problems, the building-up of forms and the relationships between them; but as paintings, I feel there’s too much picturing going on in them. One doesn’t have quite the same immediate physical relationship to them. It’s to do with scale: the scale of the body in relation to the scale of the painting.

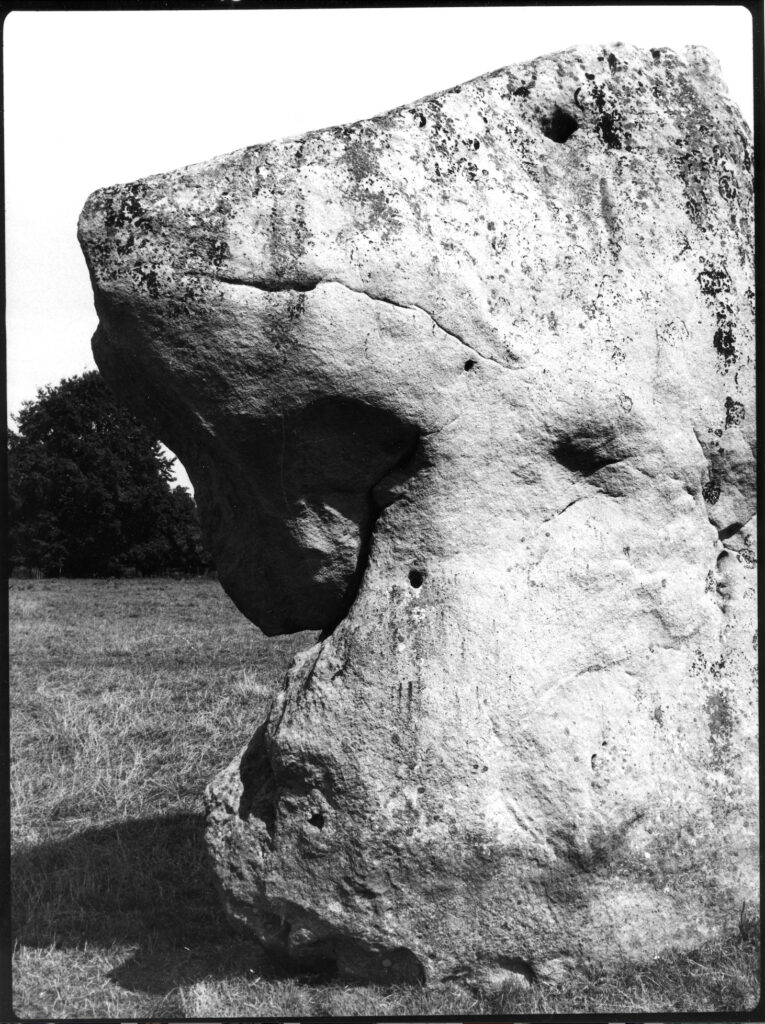

MD The initial impetus for the ‘Henge’ paintings came from a series of photographs you made of the standing stones at Avebury, in Wiltshire. From what I remember of walking round Avebury myself, some years back, the measurements of the stones are not far off the measurements of the biggest of your three formats…

IM I didn’t consciously set out to work that way, but you’re probably right. I may well have been using those measurements as a subconscious yardstick.

MD So, logically, if that’s in your mind somewhere, that direct identification between the stone and the painting, then by taking the scale of the paintings all the way down to the size of your smallest format, they’re no longer the thing itself, but a representation of it?

IM Yes, exactly. And so they become too much image, and not enough physical presence.

MD So what about the medium-format ones?

IM They still hold onto their physical presence as paintings, body to body, as it were; which is for me always the crucial issue.

MD I’m reminded here of a paradox that a lot of Giacometti’s tiniest figure sculptures, for example, seem to address: that one is being confronted with a physically present piece of sculpture, right in front of one in the gallery space, and yet so small that it registers as a figure seen from far away, from across a city square. It’s as if the shrinkage of Giacometti’s work from life-size down to tiny robs the sculpture of its absolute quality as a thing, and turns it into thing-in-a-context. You don’t feel that you could make a small painting that would register as a thing, but a thing seen from a distance, as it were?

IM Well, what you’re describing is a wonderful quality that Giacometti was able to embody in the work. Painting functions differently: when one goes down below a certain size what is experienced is different; the painting is pictured by the eye rather than felt by the body.

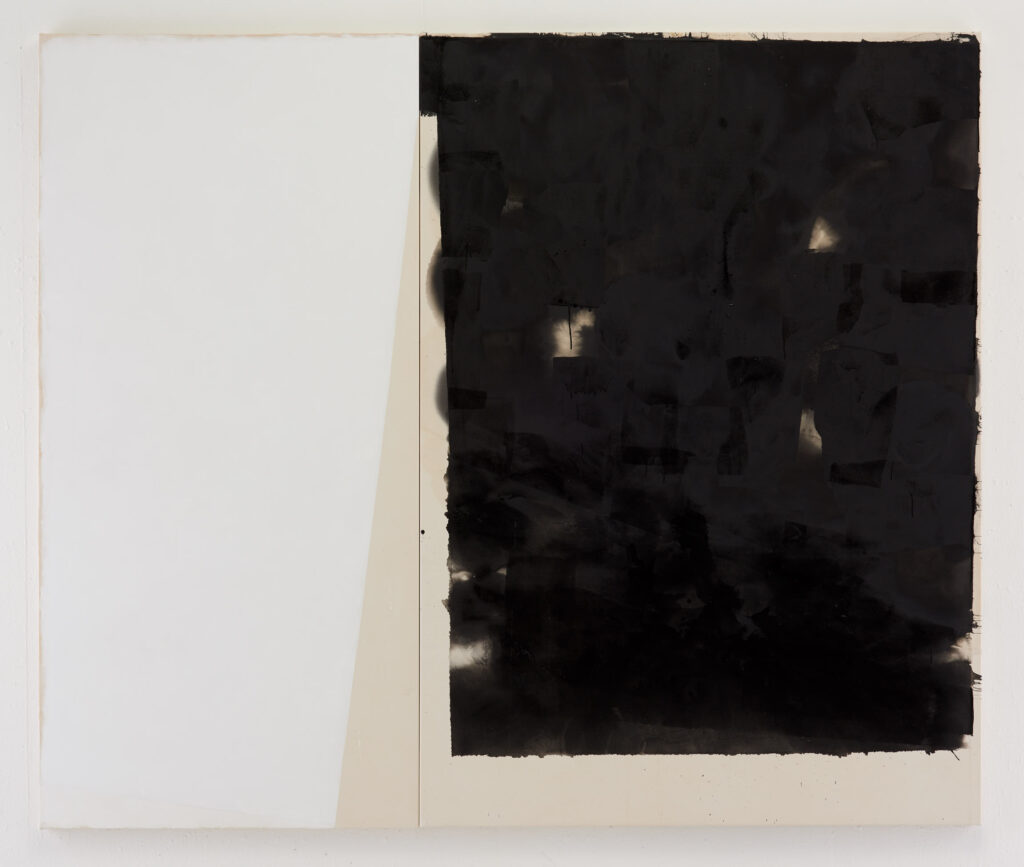

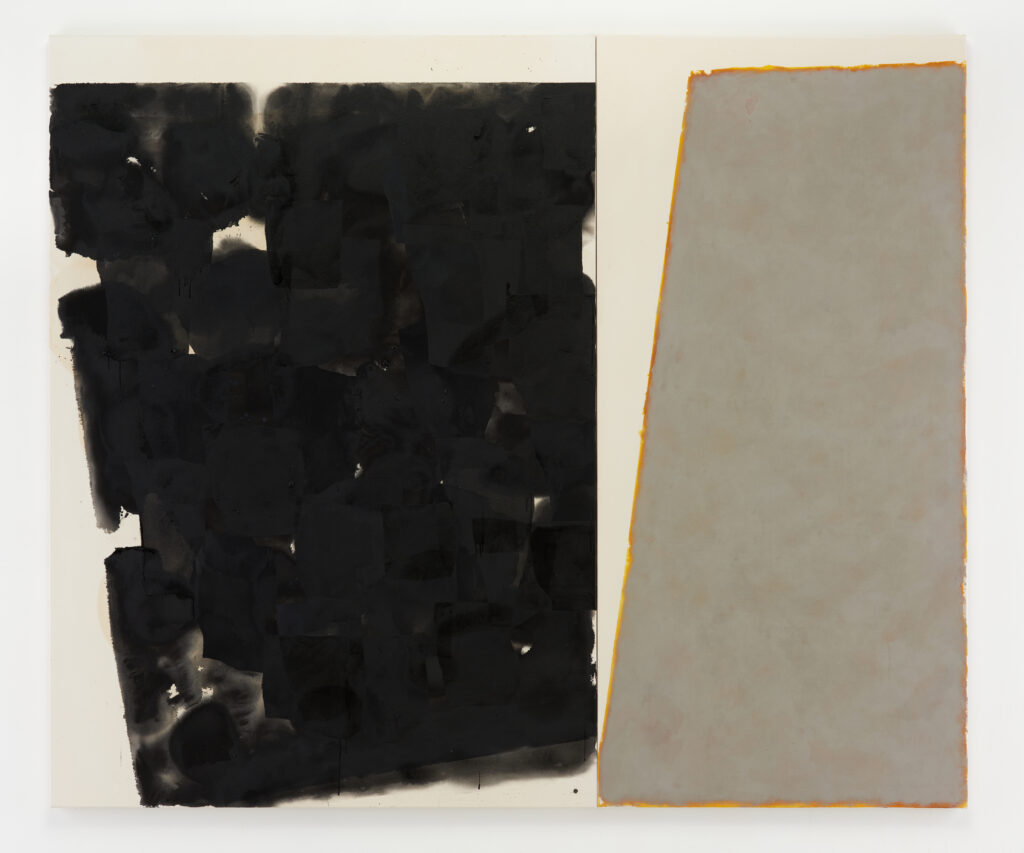

MD Related to what we were talking about earlier, of time being embedded in the painting- it’s not clear to me what sort of time was taken, building up the very sooty black monolith panels on each of these. I can see that you’ve returned to the canvas again and again, and laid in fresh areas of the black, and that these are by far the more worked of the paintings’ halves..

IM The initial painting is done on the floor, and consists of pouring and staining. If you look at the black and white one, and see the denser curved forms coming out of softer black, or the one on the end wall, where you can see those circular forms coming through- that’s understaining, not continuous staining but staining in patches, in certain places, which then sits for quite a while. All the subsequent painting, all the ‘blocking-in’ of forms, tends to be done on the wall, with the canvas vertical.

MD Judging by the almost total lack of drips, once the painting’s on the wall then you’re going in with- what- a roller? A decorator’s brush?

IM Always brushed, never with a roller; the forms are loosely stencilled.

MD Well well well. That doesn’t come across at all…

IM I tend to dislike paintings in which the paint is dripped for the sake of it.

MD I like a good drip. But I admit, a little goes a long way… (laughter)

IM They happen; there are drips inside some of the blacks, but I consciously try to avoid them. So, once the initial staining is dry, the paintings are hung vertically and then the stencilled areas are brushed on, using cheap German decorator’s brushes, which I buy in bulk. The rather loose edges are made by using roughly-torn newspaper as a stencil; a word I’m hesitant to use, as it sounds rather formal. I use the torn paper rather like a form of drawing, dragging the painted line against the ragged edge of the paper line, and it gives me a somewhat organic quality, which feels very different to a brushed edge, and to the self-consciousness that the brush seems to bring with it; it allows me to bypass this.

MD And it’s important to you that it’s not clear by what process the paint has been applied? That it’s not an autographic mark, or a stain, or a pouring?

IM No, I don’t want to lapse into mark-as-signature; I want the mark-making process to appear organic, to appear natural, to appear as if it’s found itself, rather than being the outcome of conscious intent.

MD You want to reduce the sense of intervention to a minimum? To eliminate all trace of agency?

IM Well, certainly the agency of the brushstroke, of the arm or the wrist passing through the air and making the mark. I want to avoid the ubiquitousness of a certain kind of mark-making.

MD And are you continuing with a practice I know you’ve used previously, of going in through the back of the canvas?

IM Not so often. I did in ‘Henge I’, the painting on the end wall, in the area that I spoke about earlier, with the ovoid shapes coming through: they were put down on the reverse side. I looked at it when it was leaning on the wall with the back facing out towards me, and I realised that I found it more interesting than the front. I took the canvas off the stretcher, turned it round, and tacked it back on again. In effect, the back became the front.

MD I’m guessing that’s about as anarchic as things ever get for you, in the making of the paintings. This is something I wanted to ask you about. All the commentary written on these paintings stresses the slow accretions that go into their making; and the finished work has an authority to it, and I’m going to say, a kind of confidence- however odd that might sound as a description of paintings built up over a couple of years- and a sense of inevitability to it; and yet I find myself wondering, how many shocks, how many accidents, accrue during their making, and whether you work with and around these accidents? After all, you’ve been staining paint into the canvasses for so many years now, since the ‘Door’ paintings of thirty years ago, and you must be amazingly well-acquainted with how paint behaves; its different viscosities, its properties…

IM Yes, but you don’t always get it right. You think you have, but you see it’s gone down too thick, or too thin, or it simply isn’t reacting with the canvas in the way you’d thought it would. And sometimes you find yourself spending a whole day looking at a painting, trying intensely to figure out what you should do with it; and then you just get up and do something. You thought you had to do this: but you end up doing that instead. It has its own rationale, one seems to be working it through in one’s subconscious.

MD Control, versus letting go: I’ve seen it before in your work. I remember looking at your ‘Traditional Landscapes’ at the Nigel Greenwood Gallery, back in the early 1980s, and thinking you’d posed yourself an interesting dilemma, whereby working onto the photographic ‘ground’ with your painted marks meant that one false move and you’d have obliterated the wrong section of the photographic image; and that even if you wiped it back with a rag and some turpentine, it would still look fretted, worked over…to me it was a difficult balancing act, judging how much paint you could add into the image, whilst preserving the differential between paint and photograph.

IM It still goes on. One can see the analogy: the understaining in the work now is the equivalent of the photograph-

MD Well, in visual terms, it strongly resembles it-

IM Yes. The overpainting I do now is the equivalent of the overpainting of the photograph. The correspondence is there.

IM I’m a great believer in the idea that starting a painting is to begin to finish a painting.

MD As in T S Eliot: ‘In my beginning is my end.’

IM Yes. I think that when one starts a painting, it has its parameters, its territory; and all you have to do is be cognisant of this, and stay with the painting. You can’t be flippant, you can’t be cavalier; you’ve got to, as it were, honour the painting, and see it through.

MD For so many abstract painters working out of high modernism and maintaining links with a gestural form of abstract painting, a great emphasis is placed on this sudden flash of inspiration, or on following the impulse wherever it might take them. You’re much more circumspect about all of that.

IM It doesn’t work for me: and I don’t think it works for a lot of the painters who do do it; it so easily becomes gratuitous. I have a set of parameters that I’m trying to work through within a group of paintings. For instance, if you take the ‘Temple’ paintings, it was a simple premise: that I had walked into a temple in China, that was made out of wood; a large building, with a huge roof which was held up by maybe a hundred of these large cylindrical pillars, placed only ten feet apart. It had an incredible physical presence, the weight of all this wood, and yet at the same time I was thinking, hang on, this is a temple, a place of the spirit. I began thinking around the relationship between the spirit and the mass of the space; the incongruousness of these two things together, the ponderousness of the building and the elevation of the spirit. For me, that was the starting point for those paintings.

The starting point for the ‘Henge’ paintings was visiting Avebury, and standing next to one of the large standing stones there, and just feeling that discrepancy between the physical weight of the stone, its monumentality, its age- and my own transitoriness, my own fragility in relation to it. That’s enough for me to paint a group of paintings. How do I manifest that, how do I find a framework for all of that? Should they be vertical paintings, should they be horizontal paintings? Should they be big, or should they be small and more intimate? In the case of the ‘Henge’ paintings I thought, well, I’m dealing with two almost irreconcilable opposites: this monumental stone, and my fleeting presence. It felt as if the paintings should be diptychs, a format I’ve worked within many times; and it’s from this the group grows. Spontaneity, therefore, doesn’t come into it: what does come into it is the persistence of working on the paintings, not with any kind of rigidity, but with a certain kind of fluidity that keeps it all open. It’s analogous to sitting down at the dinner table with someone, and you’re talking, and you have a wonderful dinner, and the conversation goes all over the place; but at no point during that conversation does anyone start throwing things across the table (laughter). I’m in conversation with the painting, this too has its parameters and its protocols, and I don’t want, just for the sake of fun, to start throwing paint.

MD You’ve created a set of working conditions that in some senses feel strict to me; and yet I’m not using that term disparagingly, because the results, for me, justify whatever protocols you happen to have set up. It’s clear that one of your protocols is the strict limitation of colour…

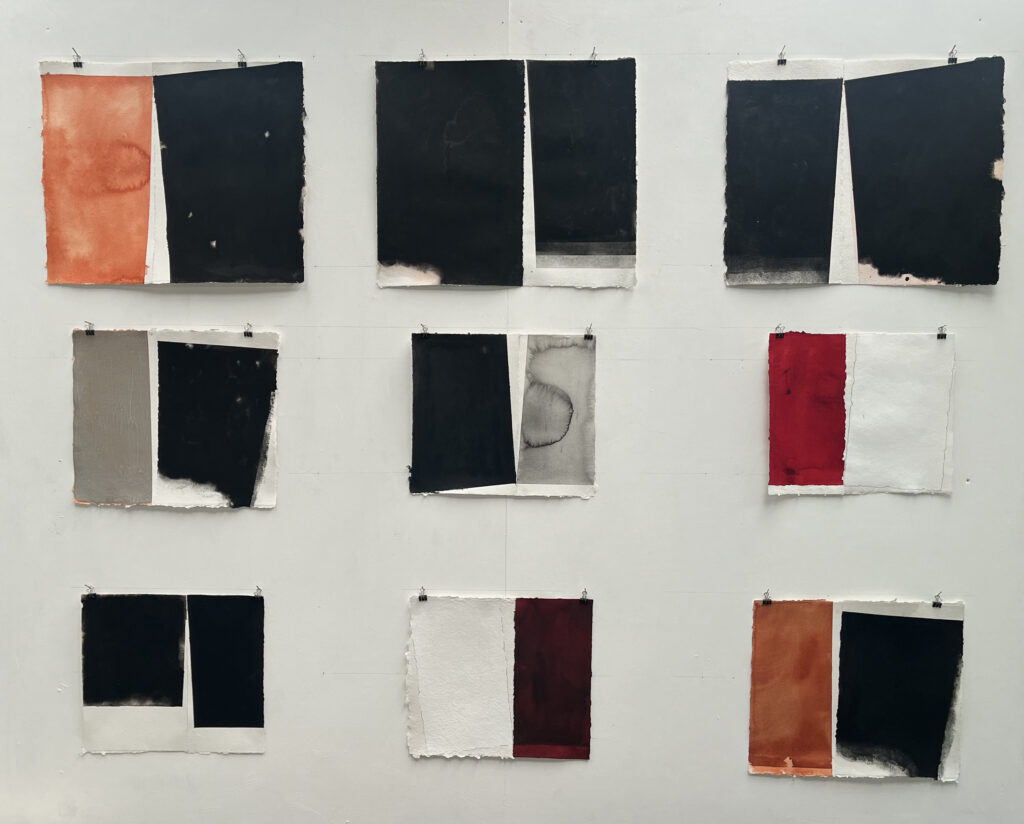

IM I work a lot with black and white; and occasionally, as in these ‘Henge’ pieces, colour comes in, and whilst it isn’t monochrome, the palette is fairly reduced. I don’t have the option to suddenly decide, oh, it’s going to be red, or I’ll put a bit of blue in here, and a bit of green up there, and a chrome yellow down there; I think there are artists who knit paintings, and then there are artists who see the whole painting all at once, and I see the whole painting all at once.

MD You don’t use colour in a part-to-part manner.

IM No, I have to see the colour as being inseparable from the total body of the painting.

MD Colour, for you, is about a form finding its colour, rather than a colour finding its form. Your use of colour, as I understand it, is very much to do with colour being a presence in the painting, an entity, rather than something that’s ground up, and kneaded, and pulled about, as Frank Stella once disparagingly described it…

IM The colour has to become the form. The form and the colour have to be one and the same thing, they have to find themselves in relationship to one another. In the ‘Henge’ paintings I tried using several colours in the narrower, monochromatic sections; but frequently I couldn’t get the colour to embed itself within the form, to become the form.

MD Here, in ‘Henge XVI’, where we have the yellow ochre coming out from beneath the grey, is that a case of overpainting in order to adjust the colour?

IM It’s a combination of not wishing to make the form look particularly hard-edged, to have the line look as if it’s organic, as opposed to heavily-taped; and at the same time moving towards what the colour/form should be. My initial thinking was that the form should be more ochre-like, but I realised as I went into it that it wasn’t working. The colour would not embed itself in the form, so I moved over towards what you might call this warmer sandy-grey colour.

MD Yes, that colour, it’s kind of unnameable: the nearest I can get is to call it raw umber, but that’s not right…

IM I was actually trying to replicate Windsor and Newton No.2 Warm Grey Gouache (laughter)-

MD Ah yes, exactly, I thought so. What you just said (laughter)-

IM …which is this warm, almost stony grey. I would love to know what actually goes into Windsor and Newton’s Warm Grey No.2…

MD Is that grey gouache the pigment that features in the works on paper related to the ‘Henges’?

IM Yes.

MD So the works on paper were executed before the paintings?

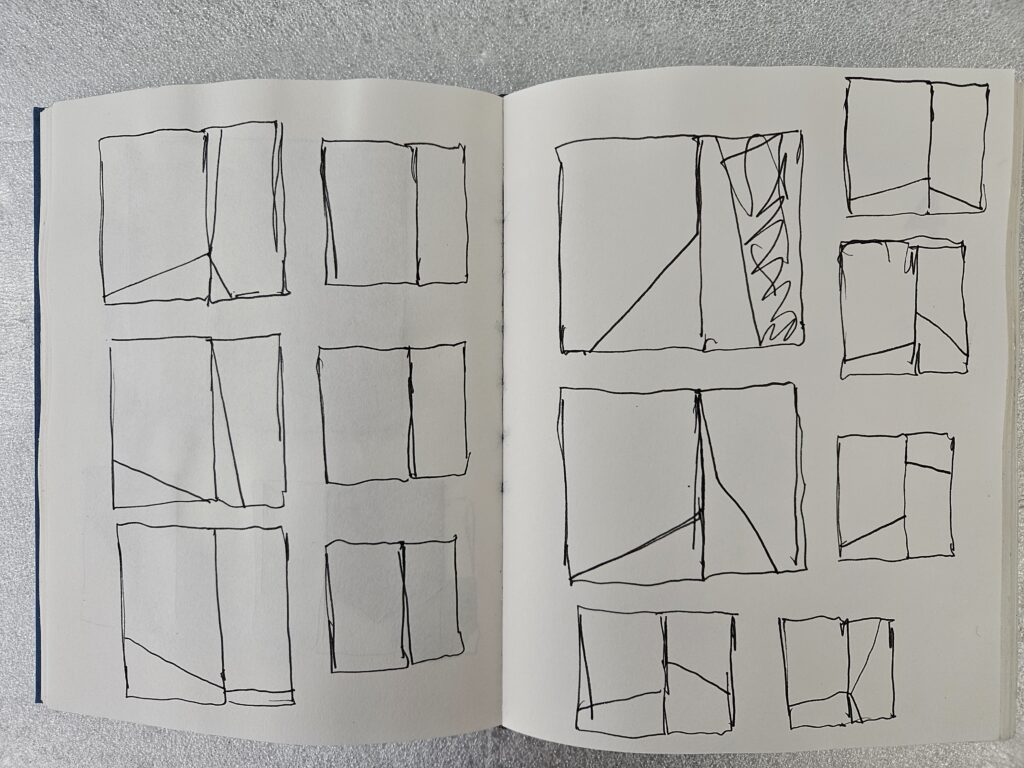

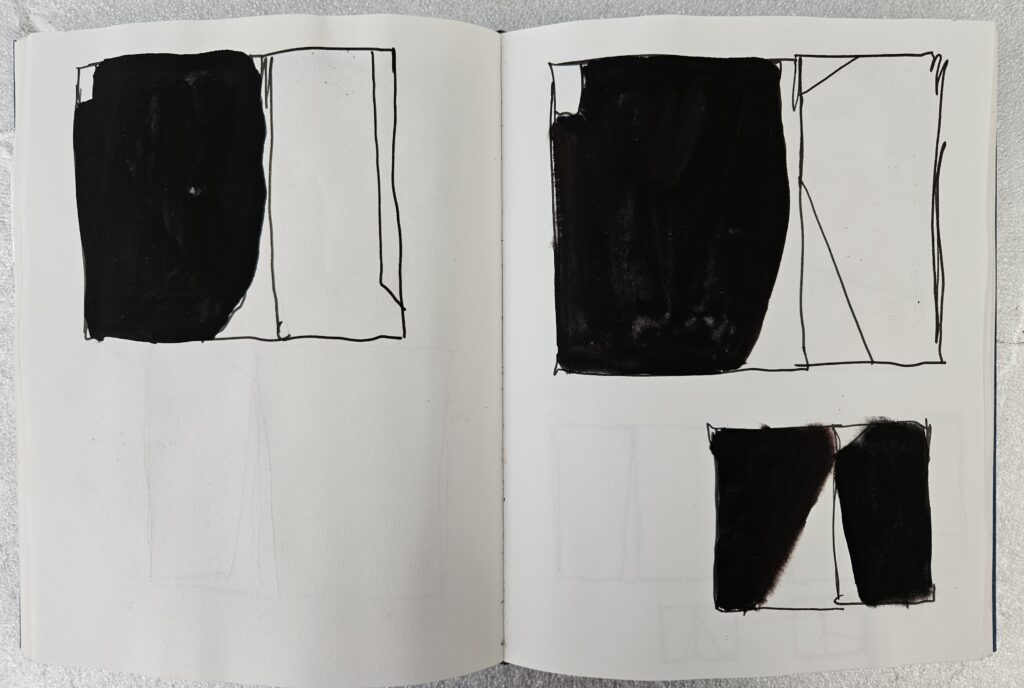

IM No, the paper works are always made after the paintings, always. The closer I get to imaging a painting before I start it is in a small notebook, where I make a simple pencil drawing or a felt-tip pen drawing, of maybe a shape, and of what might go next to it. But beyond that I don’t do any preparatory studies at all.

MD Why not?

IM I don’t want to pre-empt what the painting might be, or limit it, or lay down preconditions for it. I try each day to come to the painting as if I’ve never seen it before in my life; and that’s one of the reasons why I work on paintings and then put them away for months. I want to forget the painting, and I want to come back to it as if having a first encounter, a new experience; and in that new experience find the painting for what it is, rather than what I thought it should be.

MD This wish of yours surely carries the implication that you didn’t make the painting- or even, that nobody did? That there’s no author, no maker?

IM All of this boils down to what Brancusi said, that the artist needs to leave his or her ego behind. I don’t wish to impose myself; the painting must find its own agency.

MD So the notebook drawing is just a little schema that you’ll make?

IM Yes, and I make hundreds of them, there’s books and books of them, that I keep ongoing all the time.

MD But that schema might go by the board, once the painting starts?

IM Well, then I’ve got to begin to feel the painting, the painting’s presence. And that process begins with the stretching-up of the canvas, or in the case of the ‘Henges’, the two canvasses, which I’ll put up next to each other on the wall. It’s a little bit like when you meet someone for the very first time, and you’re only with them for two minutes, and then they’re gone. You can’t remember, say, the colour of their eyes, or the shape of their nose, but what you do retain is a very distinct feel of the person, of their energies, whether they have a lot of energy, whether they were nervous, whether they felt solidly rooted on the ground. All that, you pick up very quickly; and I’m seeking its equivalent in the blank canvas.

MD So I’m wondering: with your ‘Portrait of a Woman’ paintings, did you have a particular person in mind, or even perhaps a conception of a historical figure of a woman? A particular personality as a starting point?

IM No. My starting point was a very simple thing: if you look at most early renaissance portraits, up until the end of the fourteenth century, they are all in profile; and it’s only around the beginning of the fifteenth century that they turn, becoming full-face. This shift from profile to full-face, returning your gaze, fundamentally changed the nature of painting. Suddenly both the depicted person and the painting itself are facing back at you. I was interested, in reading about early portraiture, in how many of these portraits are not pure portraits, but archetypes, idealisations. They are like Vogue shoots: the warts-and-all, the broken teeth, the wonky eye (laughter)- all that’s been taken out, and all these young women have been totally cleaned up, and just look immaculate; they are immaculate conceptions. The renaissance painters were incredible at turning the sitter’s attire- dresses, capes, headdresses, etc.– into beautiful formal painting problems. Just think of Goya’s piggy-faced princes and princesses, relative to the love he imbued the black-laced satins and silks with. There’s a wonderful Rogier van der Weyden painting of a woman with a formal starched white headdress which comes down tightly either side of her face across her shoulders, literally framing the face. It’s an absolutely gorgeous painting.

The ’Portrait of a Woman’ series grew out of these concerns. All my paintings are rooted in abstractions. We talk about this word ‘abstract’, which, of course, doesn’t really exist in painting; all paintings grow out of something, however, there is a distinct difference between starting a painting based on something which is concrete and real in the world, say a tree or a chair, and starting a painting based simply on a thought, which is far more abstract. Most of my painting beyond a first momentary encounter comes out of abstract thought, grows out of pushing painting back to a thought process. In a way it attempts to visualise thought as a lived experience.

MD I recall what you said about the thinking that went into the creation of your ‘Diptychs’: you talked about having a sense of levels, and thresholds, and that was about as far as you were prepared to go in terms of explaining what it was you were aiming at in those works. It was about sensations, wasn’t it, rather than specifics…

IM The ‘Diptychs’ started out with my having painted a series of paintings that I wasn’t very happy with, which I was going to throw away; but rather than doing this, I decided to obliterate them by overpainting them towards black, yet at the same time feeling the need to bring something more affirming into play. So, I made a second painting which I paired with the blackened half in which I started this new half from a blank canvas. The works became a push and pull between one half of the diptych receding towards a blackened surface, in a sense losing the image, and the other half a new emerging image. The Diptychs were the first paintings in which I recycled works I felt were failures, something I still continue periodically to do.

The diptych format is a structure that I go back to every once in a while; I’ve come back to it in the ‘Henge’ paintings.

MD What, for you, would be the difference between a single, horizontal-format painting measuring three by six metres, and a diptych formed by two separate three by three metre square canvasses?

IM It’s a question of wholeness. If you take a large painting, and you divide it in two visually, then you have generated two sections that are less than the whole, and at the same time you have brought into play a third element, the demarcated division. However, if, on the other hand, you take two separate canvasses and bring them together, then they constitute a larger whole. It’s a strange area to inhabit, but it seems to me this difference is quite crucial; one way- the diptych- is about making two into one; the other way- the single painting, divided by paint- is about making one into two; and although it might sound like quite a simple matter, is does significantly affect how one sees and experiences the work.

MD The whole is greater than the sum of the parts? The conjunction of two panels results in a whole that is more than simply one panel added to another?

IM If you take the notion of the rectangle, it’s a whole, it’s a totality; everything you put into it, no matter what, renders it less than. Less than, if you like, the ideal state of the rectangle. If you bring two things together, they become more than, because they’re only parts, and they work towards a greater whole. You could say that painting a painting on a single canvas is the fragmenting of the whole, the breaking down of its totality; whereas by working with two conjoined canvases, something else is in play, and this intrigues me.

MD One and one is one, this is the way the mathematics works here?

IM Yes.

MD But you’re saying that the moment something is introduced into the canvas, it’s- perversely- a subtractive process, in that you’re taking away from the wholeness of the painting?

IM Yes. It’s one of the paradoxes of the rectangle: that whatever you put into it makes it- at one level- less than what it was, and also less than what it might ideally be.

Unlike a circle, a rectangle always holds an implicit cut-off, an implicit delimitation to wholeness. Whilst a circle is complete unto itself. Painting- any painting- somehow holds this dichotomy within it, is somehow an attempt to circle the square.

MD Which begs the question, why then have you never painted using a circular format?

IM Because I wouldn’t know where to begin (laughter). I wouldn’t have a clue how to interact with something that has such total integrity unto itself. Anything I did within the circle would feel superfluous.

MD So, by setting yourself up to paint inside a rectangle you’re confronting an imperfect situation.

IM Well, one is trying to find a point of fixity, of stability; and that appears to make sense, to have a meaning within the format of the rectangle. It’s such a huge issue.

MD And so there’s a sort of perversity to choosing the diptych format? Double trouble, as it were; the conundrum of two rectangles rather than one…

IM Or you could say I’m trying to take the pressure off both of them, so that they find some kind of steady state that isn’t perfect, but that is nevertheless a settled state between the two of them.

MD I also think it’s a very congenial format for you to choose, because to me it seems to marry well with many of your other concerns, in particular your exploration of the self and the other, if you like. Looking through the catalogue of the ‘Henge’ diptychs, I was struck again and again by the action happening at the meeting point of the two canvasses, which operates in some cases like a gully or a gutter, where it feels to me as if something has slipped away down this division between the work’s two halves, and there’s an absent content there, if that makes sense. In other instances- and we’re looking at a good example here- we feel as if we’re missing out on some crucial element, something that would explain how this interaction between the two halves comes to be happening…

IM There’s a very beautiful painting, the ‘Annunciation’ by Simone Martini, in which you have the archangel Gabriel on the left side of the painting, and the Virgin Mary on the right and a large central area of the painting unoccupied. This empty space is redolent with meaning, the power of the painting could be said to be held in this space, its sense of expectancy. To some extent, the ‘Henge’ paintings are about that gap between the two halves, that pregnant space, if you like; and of course, in the Simone Martini, it really is pregnant space, in terms of the painting’s message (laughter).

How do you leave something out, or push it so far back that it appears not to be there, and yet its apparent absence is a weighted presence? The title of NF Simpson’s play, ‘A Resounding Tinkle’1

First performed at the Royal Court Theatre in 1957, A Resounding Tinkle has been described as both “unstageable,” and “absurd.” The play apparently inspired the work of later comic geniuses, such as Peter Cook and the Monty Python, and was one of Eric Sykes’ favourite pieces (the play was broadcast as part of an extended tribute to the great scriptwriter, actor and all-round comic genius).There is no plot to speak of: Bro and Middie Paradock (Deryck Guyler, Alison Leggatt) are sitting at home drinking nectar when there is a knock at the door: Middie answers it and tells Bro that he has been asked to form a government, a task which proves difficult, if not impossible, at six o’clock in the evening. Uncle Ted (Betty Hardy) comes in having undergone a sex-change operation; while the family are still happy in one another’s company, it proves difficult for Bro and Middie to think of him/her as a man. The couple become quite concerned, when they believe that inanimate objects have been rendered animate: “There are knives in the drawer if they want to go at each other.” Other subjects for debate include the couple’s pet boa-constrictor, the difficulties of living in a bungalow (which might or might not have two storeys), Bro’s gum-boots, and dinosaurs. Oh, and we must not forget the parody-sermon that forms an interlude to the action.Originally broadcast in 1960, Charles Lefeaux’s production proved how well a play like this can work on radio – as opposed to the stage. The medium can create its own worlds through sound and voices; concepts such as ‘realism’ and ‘truth to life’ seem insignificant. The two actors – Guyler and Leggatt – came across as a perfectly ordinary middle-class suburban couple, treating absurd subjects as if they were daily occurrences. By such techniques they underlined the randomness of our existence: what we think of as “normal” might actually be “abnormal” in different socio-cultural contexts.For aficionados of the absurd, this comedy offers a feast of verbal pyrotechnics. https://laurenceraw.tripod.com/id1278.htmlspeaks about how a ‘ping’ can be far more powerful, far more weighted than the loudest bell.

One thought on “Matt Dennis in conversation with Ian McKeever: Pt 1: ‘Presence and Absence’”

Thank you Matt for your excellent preamble, good questions and Mr McKeever for your answers.

‘…appears to owe no debt to the known lineages of abstraction’. Really? Others might provide lists, but I provide Barnett Newman and his ‘Zip paintings’, leading to his ‘Stations of the Cross’.

‘Henge I’ is a damned good painting, and others in the series. I find fault with the thin line made by abutting two canvasses together, a fault shared with most contemporary diptych art. The gouaches from 2021 look great. I have not seen and reproductons are not clear, but showing the Rogier van der Weyden tells us of your sources. ‘Aa II’ is no failure as Pollocks ‘Portrait and a Dream’ is; and this tryout has led somewhere.

However, my eye rests on the ‘Temple’ paintings. They are original and new as is your thought to ‘visualise thought as lived experience’. Deriving from the Ming Yongzhe Temple, the painting ‘Temple FQ’ with its columns obscured by a loosely-brushed white mist looks like a masterpiece.