Susan Roth: Adventures with Morris Louis

‘We must look and look and look till we live the painting and for a fleeting moment become identified with it. If we do not succeed in loving what through the ages has been loved, it is useless to lie ourselves into believing that we do. A good rough test is whether we feel that it is reconciling us with life.’

Bernard Berenson1Berenson, B., ‘Italian Painters of the Renaissance’, 1952

I first saw the paintings of Morris Louis at his memorial exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in 1963. Somehow, I had forgotten, until the moment when I pulled all the Louis books and catalogues off my shelf. Amongst them I found the catalogue of this exhibition. Here I begin my search to understand my own statement: Louis is more radical than Pollock or Picasso.

My maternal grandfather was often charged with supervising my Saturdays, which was perfectly fine with the pair of us. We entered the Guggenheim Museum on that day in 1963. He paid, and as was our usual museum fashion, we began our walkabout, he doubling back and quickly exiting the building, leaving me to wander. We met up some hours later in the bookshop where he purchased the Louis catalogue for me. These forays were our secret.

I was very young then: however, the feeling of grandeur, the big fullness of feeling for Louis never left me. From this moment on, gazing at a Louis painting gave me a sense of permission that shifted my understanding: I began to feel anything might be possible. There are so many types of beauty, a sheer plurality of possibilities. Now, with this pile of pages at my feet, I began searching for my meaning and for the potential opportunities that Louis had revealed.

In Lawrence Rubin’s interview for the film project, ‘Morris Louis: Radiant Zones’,2Withers Reporting Service, 1980 Rubin struggled, choosing his words carefully when retelling his own responses to inquiries made of Louis from interested collectors and artists. ‘Everyone looking at the pictures presumed Louis to be a happy man’, Rubin claims; in fact, we learn that Louis was ‘taciturn, very tough and not what you would call open.’ He was hard-working, focused and driven by fabulous integrity. Describing his visits to Louis’ studio, it seems that Rubin came to understand that what Louis was attempting to achieve, and the extent of his involvement with his materials, demanded extreme privacy. Sacrificing everything for passion, Louis was in fevered pursuit; creative success requires hard work. Here a new understanding of tradition emerged, of painting’s craft. Louis’ courage manifested itself in a committed form of living.

Like Giorgione before him, enigmatic figures both, they changed visual language and their pictures elude meaning. What we know is what they share: both painted in luminous colors, not dark/light (though Giorgione painted on dark grounds, Louis on unprimed canvas) neither artist relied upon the contrast between dark and light colours. With each there is no backdrop, the work and the viewer connect through a shared sense of intimacy and vulnerability. We feel the two painters’ sheer density of decisions. Inviting us into this intimacy completes the picture; the moment suspended as we sense this offering. Our gaze is slowed. The naturalness of each painter, the space felt between figures or events, remind us of what Berenson extolled of human experience: the ultimate test of reality, he claims, is touch, calling it ‘rendering tactile values in retinal images.’ We know this as what is called ‘hand’, the artist’s touch, changed by Giorgione and Louis- both forerunners of colour painting- and bringing about a fundamental shift in the art of painting. We witness this translation of sensation as our visual language changes, and our interpretation depends on our ability to see painting in this new paradigm. These artists set their pictures free by adding new visions from their studio practice. For those that follow, the struggle with the myth (that process is more important than product) renders process as both subject and content.

We know little about the handmaiden bringing change to Giorgione; we well know Louis’ apprenticeship. The best of writers (in English) have laid impressive groundwork for our understanding of Louis’ art. Investigating my stack of books, I began a process of revisiting favorites: Lawrence Alloway,3My first catalogue, Guggenheim Museum, 1963 Michael Fried,4MFA Boston catalogue, 1967 and Dore Ashton.5Milan exhibition catalogue, 1990 It was re-reading John Elderfield6Hayward Gallery exhibition catalogue, 1974 that gave language to that which is central to my understanding of Louis, namely, my sense of the radical nature of his picture-making. For Elderfield, Louis ‘investigated the physical conditions of painting’s existence, inquired about the very identity of painting itself.’ Louis’ genius reinvented what painting is and might become. Louis built a visual language as abstract as music.

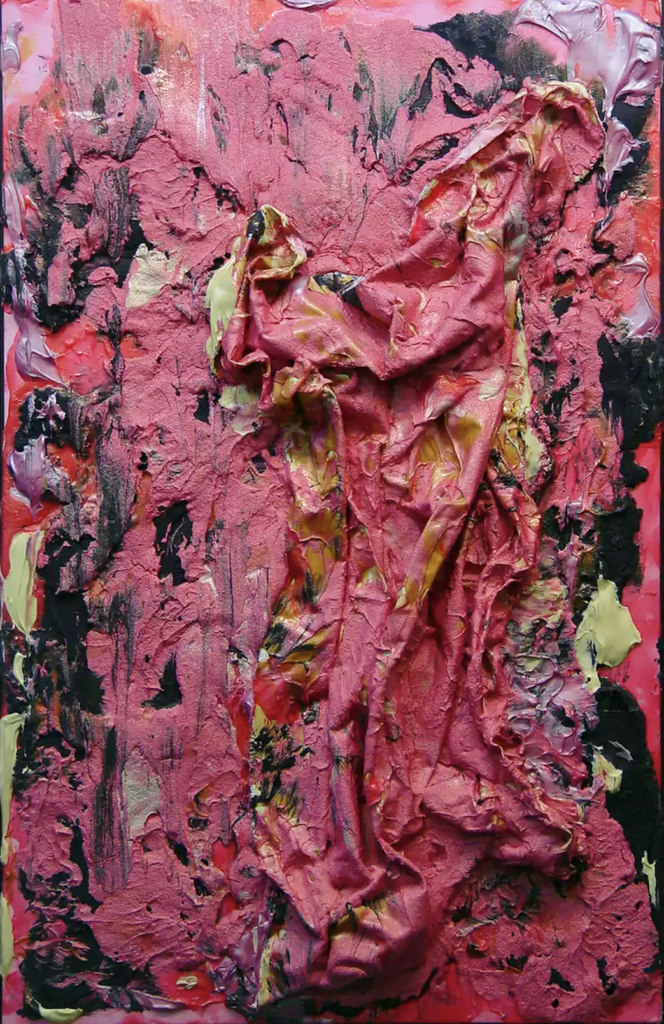

I think now of my first investigations into paint’s physical properties, prompted by the need for materials that would facilitate my means. In 1980 I called Sam Golden, Morris Louis’ paintmaker. I had read about the colourmen, the paintmakers for many past artists. Sam told me stories of his interactions with Louis whilst he reassured me that with patience, and the tinkerings of trials, he would fulfill my request for heavy, thick paint to hold the roiling surfaces I dreamed of. Sam shared stories of Louis’ need for particular viscosities, of Louis wanting more than stain, of Louis’ dream of canvas and color becoming one. Sam explained how Louis usually tacked unprimed cotton duck to stretchers or to lengths of wood and poured his paint, thinned Magna. We assume he tilted and manipulated this support: but what is seldom reported– and was explained to me by Sam– was Louis’ use of mineral spirits to break the surface tension of the canvas, a form of invisible drawing that offered some control and boundaries. All this to reassure me that we might find a way to make possible my dream of bunching and roiling of the picture plane or ground.

In an attempt to see Louis we must emancipate ourselves from a belief in the preconditions of luck. Our ability to see things anew depends upon our letting go of our assumptions of what freedom looks like. While it is true few are interested in the technical matters of art, these do have everything to do with art’s continuum and with its practitioners. Louis’ need for privacy, his reminding Sam not to give his paint formulations to anyone, his refusal to discuss his manipulation of the support, none of this has stopped us wanting to understand his practice, his completely abstract images. The difference between painter-as-example and painter-as-influence is so evident with Louis; thanks to his wild originality, you feel his example, his individual character. His influence is quite another matter: these visual works transcend understanding – they feel as inevitable as natural forces. His influence, like yeast, is everywhere and nowhere to be found.

Louis’ first major images emerged in 1954 as he was experimenting with formats and means to take advantage of the pouring of Magna. They present layers upon layers which, though weightless, leave the surface palpable. The ‘Veils’ format was one of the fruits of this early exploration, and, recognizing its power, in 1958 he began the series that bears the name. Frontal in character, and affected by the autonomy of each hue, these paintings of Louis’ offered a new view of abstractness and scale that surpassed Pollock’s openness, leaving all vestiges of cubism behind, and in so doing, changed our understanding of painting. The scale, so difficult for his dealers to sell, comes from within all Louis’ images. As Colm Toibin says of Goya, Louis is ‘history charged’, his pushing of scale ‘a reflection coming from the inside out’, a very different proposition from size, which defines itself with numbers. However, the part-to-partness, the internal changes in scale, as Michael Fried reminded me in 1990 at Triangle Workshop, are as important to painting as to sculpture; when this internal context is everything, then size matters. I am reminded of Brancusi’s ‘Endless Column’; symmetry through repetition permits a sense of forever and ever, of infinity. The success of the ‘Unfurleds’ is the unbounded space within them. Like Chopin’s touch, in each rivulet, as fundamentally different as each finger, the character of colour remains singular and in concert with itself. This multiplicity retells our story. These complex paintings, with their new language, resist our comprehension; but while the commonplace nature of our vision seems to betray or forsake art, our experience broadens as we continue to gaze.

In revisiting Louis’ quest, we find the truth of it in the doing. He left us a broad vision. As my grandson sat with me last summer we opened Diane Upright’s Louis monograph, ‘The Complete Paintings’:

‘How would I know which one was my favourite?’ he asked. So many look similar.’ ‘Of course, we are not in front of them’, I responded. (I thought of ‘The Book of the Thousand and One Nights’: it is all of them, taken together, that overtakes, transcends.)

‘Dashiell’, I continued, ‘It’s like loving ice cream. And ice cream we both know: another day, another favourite!’

Art is not meant to stop the stream of life. Within a narrow span of duration and space the work of art concentrates a view of the human condition; and sometimes it marks the steps of progression, just as a man climbing the dark stairs of a medieval tower assures himself by the changing sights glimpsed through its narrow windows that he is getting somewhere after all.

Rudolf Arnheim7Arnheim, R., ‘Entropy and Art’, 1971

10 thoughts on “Susan Roth: Adventures with Morris Louis”

I found this riveting – beautiful writing about painting, thank you Susan, and Instantloveland.

Susan Roth on Louis. Wow. Great artist on great art. Like the late, great Robin Greenwood justifying abstraction by reference to history painting, in his case Cezanne, in Susan’s case, Giorgione. I’m left with children completely indifferent to the passion Susan and I shared as developing artists. Yet my experience of an almost-empty John Elderfield show at MOMA has completely dominated my life since I experienced it. But it was Louis’ breathing surfaces that I found so compelling, Frankenthaler the only rival in this regard. I think of Albers and Matisse, and Braque (so groundbreaking), colour versus tone, the same dilemma Louis faced. I also have the same books as Susan. I’m not sure Louis improved later, though. I think he started off great, without the influence of Noland, painting the ‘Veils’.

The word I meant to say was incredible Romanticism. Helen Frankenthaler had it, Louis captivated with his vision. Bob Dylan and Miles Davis caught it occasionally too. Necessity of great art. So hard to sustain.

A very insightful and thoughtful article, Susan! I felt the same way when I first saw Louis’s canvasses in the flesh when I was younger. Standing in front of them so all I could see were the veils of colour in my eyesight. Your collection of Louis catalogues is also admirable. I also love yours and Dashiell’s interaction at the end. You are right that you tend to pick a new favourite all the time. Today, the favourite Louis painting is ‘Green by Gold’, 1958.

Susan’s feeling and idea that Louis is more radical than Pollock or Picasso got me thinking…and looking. I see her point. It may be a close call with Pollock as his all-over pictures helped to usher in colourfield painting and I assume that she is referring to cubism with Picasso but not completely sure. I would agree that Louis’s pictures are certainly more radial than any cubist picture..and it might be that sculpture got a bigger kick from cubism than painting did even with how entrenched cubism still is in so much painting. For me it is the sheer encompassing beauty of a great Louis ‘Veil’ painting that remains and sticks with me. More beauty than Pollock – for me. The radicalness does seem to reside in his process, methods and materials where he so carefully and masterfully directed mineral spirit acrylic stains on such a large scale. Much copied, and at least so far, nothing comes close that I have seen. And speaking of radicalness, I’ll go on record to say that I know Susan’s work, and have been looking at it for decades now. I think her pictures – her best ones – have this quality in the way she takes collage to a new level combined with shapes that come out of the art making process (cropping the work to find the shape – find the painting), rather than the much more common method I see where an artist creates a shape and then paints it. And then you have her colour sense and touch along with a deep understanding of her materials. So I think she shares something here with Louis (and others) and it is rare indeed.

Wonderful article on Louis by an insightful artist and writer. Thank you!

I must have forgotten to post my full name, it’s Mark Raush

I would have welcomed more, Susan, about Louis’s working methods of which you know a lot but seem reluctant to divulge. You reveal that Louis used mineral spirits for ‘invisible drawing’ and to determine the flow of paint within wanted boundaries. Ken Noland explained to a small group of us sculptors in London, that he tacked large canvas edges to trestles, allowing him to manipulate the painting and control paint flow. Your writing that Louis used mineral spirits explains much more about how the rivulets were acheived. Louis would doubtless be looking at the huge empty centres, allowing his peripheral vision to see the totality of the work he was creating (his studio was very small). When I look at the ‘Unfurleds’ I like to be close and allow my eyes to dwell on the empty centres. Distance and perspective are possible in museums : but close up makes for added excitement.

Your painting ‘Love in Town’ looks great! Well chosen to show us the heights you have achieved.

The word taste comes to mind. Living in Baltimore in the early 1970s, but showing in Washington, there I met Anne Truit and Sam Gilliam. No Louis. Kasmin was showing Noland’s stripes: radical eye, extreme taste. Helen Frankenthaler blew everybody out of the water, working flat on the floor, using acrylic and water, on bare canvas, coming out of Pollock, but with colour and feeling. Sometime in the 1980s I cat-sat Larry Poons’ studio; he was doing his poured paintings, mostly in grey, and thick, by tacking huge canvas to the top of his studio walls.He had a pitcher’s mound in the centre, and was throwing 5-gallon drums. The pictures moved all night. Radical taste. I also love Louis’ failures, his multidirectional pours. He was crucifying himself about his decision-making, catching his vision somewhere in mid-career.

Really enjoyed this essay. As a student Louis was my hero (still is). I remember once opening a book in the University Art department library and seeing two Louis paintings called ‘While’ and ‘Where’ – two of the paintings that bridged the gap between the ‘Veils’ and the earliest ‘Unfurleds’, when colour was becoming more important than ‘picture making’. I was just getting used to be being an art student and remember staring at these paintings and not ‘rejecting’ them, knowing nothing about them or their context but being transfixed by them. To this day, I can only visit his work when completely immersed in the problems of painting, otherwise forget it, it’s just too much. He is more radical than Pollock. In fact, I would say he is the first true abstract painter. It’s not the ‘Veils’– wonderfully seductive as they are. Neither is it the fact that if an ‘Unfurled’ painting doesn’t make you smile or even cheer, then you’re not really aware of what life is about. (I remember a great mate once on a business trip in Israel phoning me up whilst he was at a function which happened to be in a museum with a Louis ‘Unfurled’ on show: he was raving about it. I should say he was not an artist in any way, but he simply felt it, he knew he was looking at something extraordinary and I was so delighted to receive the call, I laughed – a great memory. No, for me it’s the paintings with stripes – though I think Louis thought of them as columns? In these we hit maximum abstract painting. There is no vestige of the pictorial here. They generate their reality through the fact-ness of their hues, firstly. Then these hues are revealed to us through the nature of how paint will behave – not forced, not employed but somehow left to ‘be’ – that is the great illusion. It takes enormous interventionary skills and dazzling technique to create the look of paint somehow existing as if the artist had no hand in it. I too have a plethora of books and catalogues -the Fried and Upright are both great but Elderfield seems to really get closest to it. Louis was ruthless in his drive. Each series was simply a step in a shark-like forward movement to get to the kill. I also spoke with Sam Golden whilst I was working in the graduate studios at Syracuse University during two consecutive summers, often hiring a car to get to Golden Paints and stock up. You Americans are so lucky to have Golden. Sam told me Louis used to say, ‘Don’t tell Ken [Noland] what I’m doing’ (now there’s an interesting addition to the historical debate!) It was Louis that got me to Matisse and not the other way around – always fascinated by that.