Matt Dennis and John Bunker on James Faure Walker: ‘Paintings and Sightings’ at Clifford Chance, London

Since early 2022, ‘Paintings and Sightings’, James Faure Walker’s show of six paintings made across four decades, has been hanging at Clifford Chance in Canary Wharf. On Monday just gone, on a rainy Halloween night, James’s family and friends gathered for a special event in the vast atrium gallery space to view the paintings, and to hear two short talks about aspects of his life and work: the first, ‘James Faure Walker: First Paintings’ given by my co-editor at Instantloveland, Matt Dennis; the second, ‘Patience and Independence’ by James himself. Having enjoyed a long and fruitful working relationship with James, as frequent contributor and erstwhile writer-in-residence at Instantloveland, we’re delighted to be able to do our bit towards helping keep his work in the spotlight- where it richly deserves to be- by publishing both talks in full, alongside pictures of the event, and of the works that feature in the show.

John Bunker

‘James Faure Walker: First Paintings‘

Speaking in 1949, Jackson Pollock had this to say: ‘There was a reviewer a while back who wrote that my pictures didn’t have any beginning or any end. He didn’t mean it as a compliment, but it was. It was a fine compliment.’1Jackson Pollock as quoted in Hunter, S, ‘An American Master: Jackson Pollock, 1930-1949, Myth and Reality’, in Jackson Pollock: The Irascibles and the New York School, Milan, 2002, p60

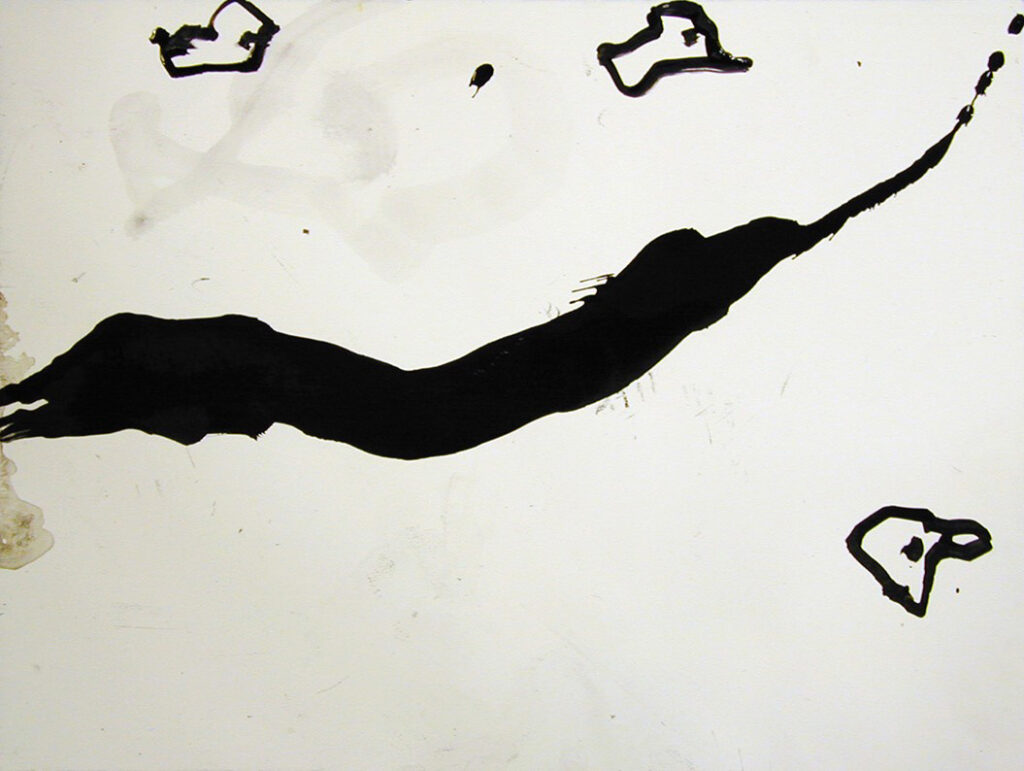

James Faure Walker’s own ‘Jackson Pollock moment’ arrived more than half a century later, at the Singer and Friedlander Watercolour Competition at London’s Mall Galleries. James had submitted a watercolour that consisted almost entirely of a single, long, splattered black brushstroke; and he overheard one viewer standing in front of the work turn to her companion and say: ‘I think it might be his first painting.’ And, when telling me this story, like Pollock before him, James was moved to exclaim: ‘It was a compliment. A fine compliment.’

He’s right, of course: it was a compliment. Every painter dreams of making a work so fresh, so unexpected, so singular that it feels for all the world like their ‘first’ painting; and since there’s no predicting how, or how often, that happy event will occur, all a painter can do is try to establish a set of open, flexible, improvisatory tactics that might, just might, allow them to circumvent their own habits, their own inclinations, for long enough for the marvellous to happen. And so, for all his hard-earned technical skill across a wide range of media, and his decades of experience of how paint behaves when it hits a surface, and his broad and deep understanding of his subject area, and of so many subject areas beyond it, I believe that for him, it all boils down to just that: how, against the run of play, to make a first painting.

In order to get some sense of the full measure of James’s achievement, in reaching the point where the accumulated know-how of a lifetime’s effort becomes the very thing that enables one to go beyond it, it’s important to look back towards his beginnings, and to appreciate just how hostile the climate of the art world had become, as the last vestiges of the optimism of the 1960s faded, and a set of widely-held assumptions regarding what abstract painting was supposed to stand for were taken apart and subjected to forensic scrutiny. James completed his studies and embarked on a career as an abstract painter at pretty much the precise historical moment when the kind of painting he was intent on making, namely, painting that looked to explore and extend the legacies of Modernist abstraction, was taking a frightful beating from all sides. For those that believed the future of painting lay in a politically committed figurative art (and there were a great many such believers by the end of the 1970s), James’s brand of abstraction was seen as too reductive, too wrapped up in its private dramas of abstract form and colour, and therefore failing completely to engage in any meaningful way with social issues; whilst for those that believed that the only path left for painting to take led inevitably to the blank monochrome surfaces of Minimalism, James’s painting wasn’t reductive enough. And then there were those for whom the fact that James was painting at all, whether figurative or abstract, was enough to condemn him to utter irrelevance, to the status of a quaint and eccentric hobbyist dabbling in a hopelessly outmoded form of expression. To give a flavour, here’s conceptual artist Victor Burgin, in an essay from 1976, describing the act of painting in vivid terms: ‘The anachronistic daubing of woven fabrics with coloured mud.’2Burgin, V, ‘Socialist Formalism’, Studio international, vol. 191, no. 980, London, March/April 1976 Take that, art history…

It says a great deal about James’s sheer doggedness during these lean years for abstract painting that not only did he continue playing with coloured mud, getting better and better acquainted with its possibilities, exploring ever more imaginative and daring ways of putting it to work in large, ambitious paintings that built richly-coloured spaces using the gestural handwriting of the brush, but he also took the bold (or very possibly foolhardy) decision not to retreat to the safety of the studio, away from the arguments raging around the question of what direction art should take, but rather, to join the fray. He did this by co-founding and editing ‘Artscribe’, a magazine that grew out of discussions between James and various artist friends in their co-operative studio spaces, and which went on to become, for a period, the UK’s best-selling art journal.

‘Artscribe’ was never wedded to a single editorial point of view, but instead, made it its mission to play host to the greatest possible number of voices, and to discussions ranging far beyond painting, into photography, performance, architecture and dance. It celebrated, rather than resisted, the pluralism in art, and in the arts, that marked the end of Modernism. And as James has explained, there were ‘as many sceptics on board as believers; the point being to keep conversations going across the whole range of opinion.’3https://instantloveland.com/wp/2021/11/22/james-faure-walker-remembering-artscribe/

‘Artscribe’ was, in its modest way, a monumental achievement: a consistently challenging forum for writing about the arts, kept afloat by the dedicated labour of a determined few, with James at the forefront; and in a shameless plug for Instantloveland.com, the online platform for writing on abstract art co-run by John Bunker and myself, I heartily recommend you all go there and read James’s excellent essay, ‘Remembering Artscribe’, which goes into delicious detail about the highs and lows, the triumphs and the tantrums of that unforgettable era of art journalism.

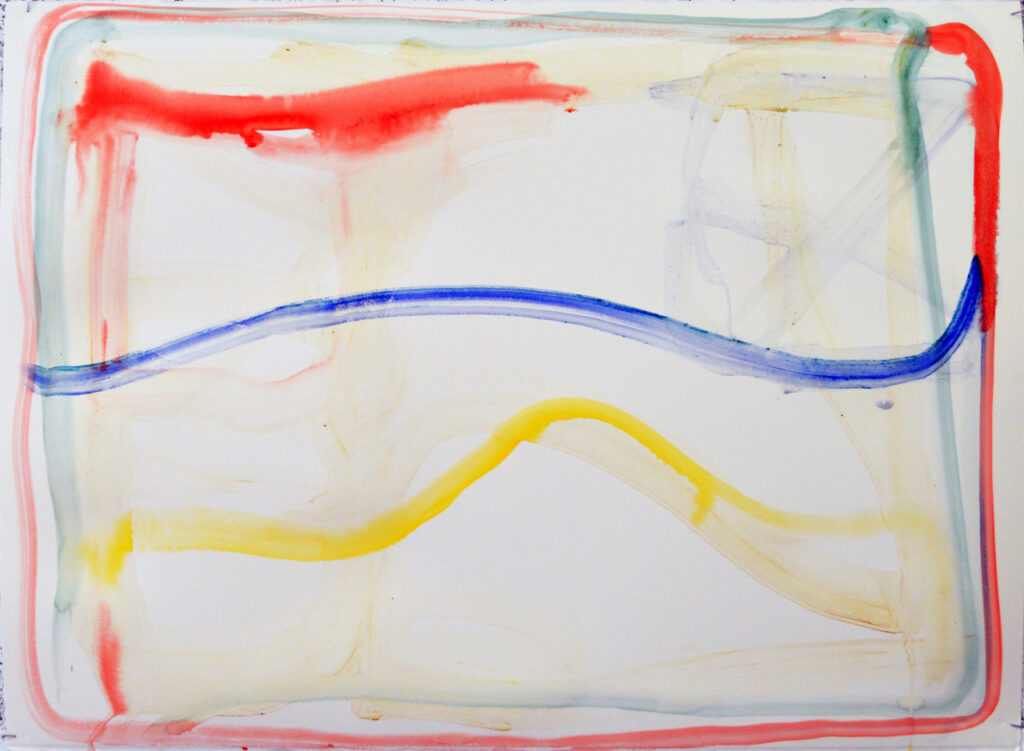

This determination on James’s part to remain open, to resist dogma, to be discursive, to be receptive to all kinds of stimulus from beyond the confines of the painting studio, has shown itself not only in his writing on art, but also in the surprising ways that he has looked both forwards and backwards in the search for fresh territories to explore in his work. This has meant, from time to time, that he’s had to deal with his fair share of resistance, if not downright incomprehension. It’s hard to imagine now, when the iPhone and the iPad have put tinkering with digital imagery within easy reach of so many, but James’s discovery, at the end of the 1980s, of the astonishing possibilities offered by the then-new discipline of Computer Graphics, which prompted him to introduce the distinctive lines and forms and textures of the early paint software programmes into abstract canvases, proved a little too forward-looking for some, back then; in particular, for the purists amongst the staff of the various institutions where James taught during these years, who wanted their abstraction untainted by any associations with anything outside painting, and who viewed ‘Computer Art’ as an unpleasant episode that would soon blow over. And yet, being seen on the one hand as some kind of dangerous radical, concocting an explosive mixture of paint and pixels in order to blow abstraction to smithereens, hasn’t prevented another of his enthusiasms, his long and serious engagement with watercolour painting, from being interpreted as evidence of the opposite tendency, as a reactionary backward look too far, to a medium that, as James himself acknowledges, carries with it inescapable associations with the picturesque, with academic and amateur art, and with kitsch. His work in watercolour is, of course, none of those things: he paints quickly, abstractly, gesturally, with great spontaneity and freedom, exploiting the medium’s luminosity to achieve a gorgeous richness of colour against the white of the paper.

I have the strong suspicion that James feels that a little incomprehension on the part of the art-viewing public as regards what he is up to is a price well worth paying for his right to play freely with his materials and his painterly means in whatever combinations his instinct dictates on any given day. He will work carefully, methodically, patiently, on a painting, right up to the very second when he finds himself yielding to the impulse to do something that throws the whole thing over, or sends it hurtling in a different direction. As he has explained, ‘I prefer the improvised, the lyrical, the fallible. Too much certainty makes me think of Jehovah’s Witnesses.’4Faure Walker, J, ‘Works in Progress’, eCatalogue of the exhibition, ‘James Faure Walker: Works in Progress’, at Felix & Spear, London, 2021, p26

I’m all too aware of how little one can really say about a career and a body of work as extensive and as fruitful as James’s, within the time constraints of a short address like this one: but luckily, we have the paintings themselves here to make the argument for the richness and range and variety of the modes and methods used in their making; and I think they make that argument wonderfully well.

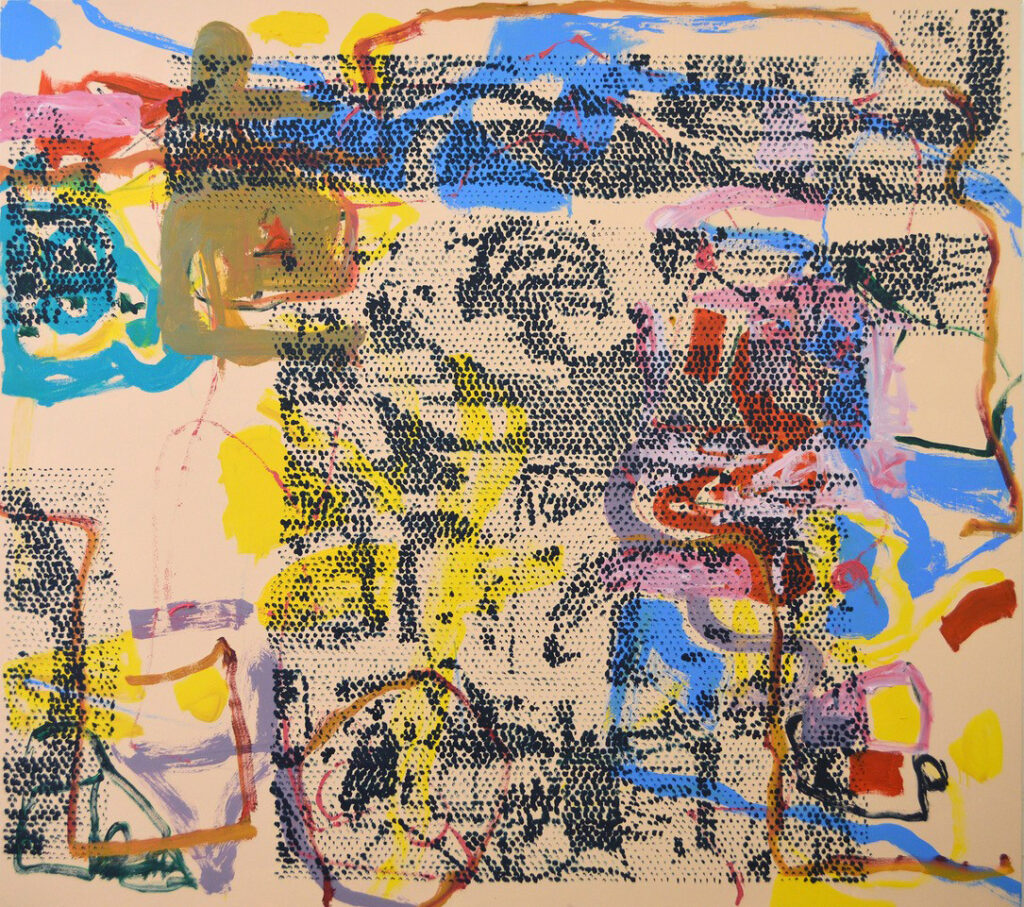

What’s striking about these large canvases, once one has got past the intense pleasurable shock of their lushness of colour, and their sheer physical presence on the wall, is the realisation of just how many liberties James has taken with the idea of abstraction, and how many games he is playing with the ways in which we read a painting: in ’Heron Island’, he pushes the forms to the very brink, so that the suggestion of the real, of floating, shifting undersea flora and fauna in the blue water of the Great Barrier Reef, becomes so strong that we are sure that that is what we must be looking at- only to have the painting pull back into indeterminate marks and forms that belong not to the observable world, but only to the movement of the brush; in ‘Marsh Harrier’ he pitches figuration and abstraction against each other, so that the layered swipes and stripes of paint are busily working to turn the bird’s black silhouette into an abstract shape, while the harrier is busily casting its spell on them, and re-casting the canvas as a tangle of branches. And in ‘Coastal’, the grainy black layer which has been painted, pixel by pixel, across the looping, brightly-coloured brushmarks, has the look and feel of an image, a crude, low-resolution picture of something; but what that something is, is impossible to say.

In each of these half-dozen works that mark a point along a forty-year continuum of painting, something is being said that will only be said once, within the borders of this particular rectangular surface, with these particular painted marks, in these particular relationships with each other. Each of these paintings begins its journey in its maker’s deep engagement with the history of abstraction, and with the life experiences that prompted him to pick up the brush: but in each case it arrives at a specific, unique point that had no existence before the painting itself defined it. To me, these feel like first paintings. And I mean it as a compliment, a fine compliment.

Matt Dennis, October 31st 2022

‘Patience and Independence’

Forty-eight years ago, on Christmas Eve, in New York, I was interviewing an eminent critic for Studio International. I asked one final question. Did he have any advice for a young artist? He paused – ‘Patience and independence.’

I am too fidgety, anxious, and in a hurry to be considered patient. But independent? Well I haven’t joined a cult, unless the Royal Watercolour Society counts as one.

Am I thoughtful, painstaking, with a sound basis for making paintings? I wish. Last week I accidentally knocked a bowl of tinted water all over a watercolour on the floor. It turned out better than the others I was working on. Perhaps that is a form of patience, waiting till your brain disconnects, and then you let the paint do the talking.

I called this display ‘Paintings and Sightings’. I have often thought the point of painting is not to reproduce what you have seen. No – for me and for other painters, and for Paul Klee – the point has been to teach you how to see. One of my treasured memories goes back to when I was seventeen. I had been working intensely on a large painting using greys and mauves. Afterwards, in the rain, I looked down at the wet asphalt and couldn’t believe how beautiful it was. I hesitate in saying something so pretentious. But may I mention that Patrick Heron told me something similar, in Canterbury, when I had driven him down there to give a talk? Except that I think he was on the verge of suggesting the roadwork scar patterning might have been influenced… by his paintings.

I used to tell my painter friends – and bore them mercilessly in the process – that digital painting was like switching on an extra segment of the brain. Even art history looks different. At one conference I was ticked off for suggesting that renaissance artists were computer graphics show-offs. Anyway, now I can walk into the studio in the morning and ask, what would happen if I put everything in this painting on top of that one, or spun it round, or put all the colour into negative, or threw a random photo over it… and then I can set about doing just that.

That critic I mentioned was Clement Greenberg. Apparently, some years later he said digital art hurt his eyes – fair comment – but he didn’t dismiss it out of hand, as did most commentators. He didn’t like paintings that were ‘easy on the eye’ – his words. Perhaps I am at fault there – the Guardian reviewer in 1985 said my paintings – including ‘Heron Island’ here – were so bland that to yawn would be to overreact.

James Faure Walker, October 31st 2022

A companion show of paintings by James Faure Walker, ‘How it Works’, runs from November 4th- December 4th 2022 at Felix and Spear, London.

5 thoughts on “Matt Dennis and John Bunker on James Faure Walker: ‘Paintings and Sightings’ at Clifford Chance, London”

Really missed seeing this show, as James is my exact contemporary. I think we have mutual respect. I reminded him of a visit we made with Gary Wragg to Brian Robertson’s house, where he had a Cezanne watercolour in the toilet. Matt is right, James’s images need no explanation, they are FORMIDABLE. For me, not being a literary critic, or computer generator, the paintings remind me of filleted fish, the shape of the bone, and not wanting to lose the flesh…the colour is surprising and I can quite see the watercolour connection. I will go and look. Whilst walking home I’ll wonder what terrible curse has the Tate had put on it, that they are not fighting to show James’s full oeuvre, and many others like Gary, Robin Greenwood etc. We have so many wonderful artists, and James is looking so fine. He deserves every success.

How lovely to read this about your work, James: I do believe we may have had a brief meeting at Farnham.

With best regards

The reproductions in your article hit me in the eye. ‘Marsh Harrier’ (2016) and ‘Coastal’ (2019) give me no idea how the digital images are achieved but they look similar to steel mesh or perforated steel sheet, and the shapes could have been collaged onto the canvas. Also lost in reproduction are what all the materials are and their feel, which must be central to experiencing the totality that Faure Walker seems to achieve. Unfortunately mobility problems hinder me presently and I could not see these paintings. I seldom make judgements from photos but they are saying something very positive. Thank you for your insight in this article, which also tells me I could be looking at new art, beyond my experience of visual art made on a flat surface.

I was fortunate to visit Clifford Chance during this show to attend another event, and I was completely blown away by the visual assault of these paintings on my senses.

This was the first time I had seen his work and felt as though providence had gifted the experience to me. They hit me like seeing an abstract painting for the first time, so fresh and stimulating. Like seeing the painting that’s been living in my head for ever, the one that never quite gets made, the one that’s trying to articulate and express itself mediated through my eyes and hands.

Only once in a while have I had such an experience, so imagine my pleasure to come across this article and find out a bit more about James and his work.

I enjoyed this show as there’s an openness to the work. I have found when working in the RGB colour space that imagery is quite at home – perhaps it is ultimately its natural home? There could be an essay in that. I felt that incorporated imagery on screen seems to slow the looking down enough to counter things looking ‘ambient’. The ghost of the screen seems to follow the work onto canvas, though, imbuing it with an otherness, which numbs the plasticity of the painting, somewhat. Sometimes if you are looking at Renaissance art it can appear very similar to the look of hand-coloured black and white photos (their darks and lights are the building blocks of forms – tonal/depth spaces etc). I’m not sure how that is related directly but if those artists were working today perhaps they would enjoy film-making. These are not tonal paintings, though they do possess a sense of the filmic. The spirit of adventure is significant and that’s to be applauded.