James Faure Walker: Remembering ‘Artscribe’

Whatever you might have heard to the contrary, it can be a tough and thankless existence here at Instantloveland, trying to run a platform for debate and discussion around abstract art. Pestering potential contributors, chasing up copy, sourcing copyright-free images, and all the while making sure to get along to show openings…there are times when all the canapés and complimentary catalogues in the world couldn’t keep us from asking ourselves: what the hell do we think we’re doing? And why?

It’s at times like these that we look to remind ourselves of what can be achieved, provided the necessary doggedness and desire are there; and where better to look than the pages of ‘Artscribe’? What began in the mid-1970s as an extension of discussions between a group of artist friends in co-operative studio spaces very swiftly grew into the foremost art magazine in Britain; and all of this happened years before ‘desktop publishing’ meant anything other than getting busy with the scissors, the glue, and the paste-up board, which only makes the achievement all the more impressive.

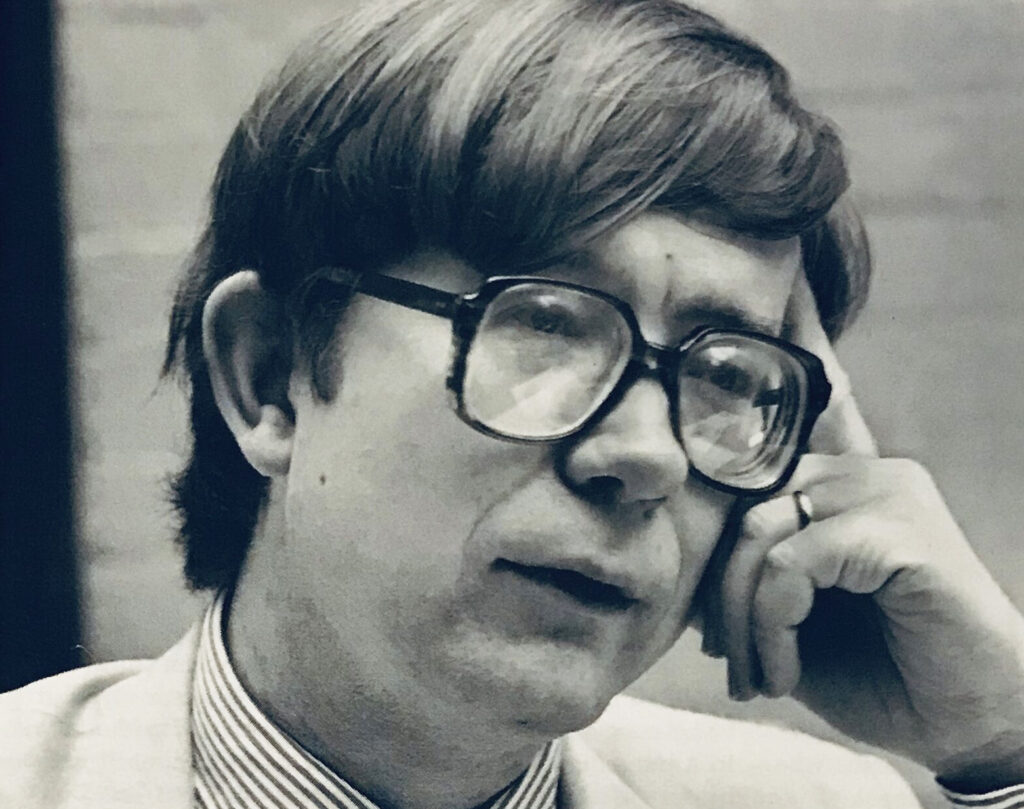

To hear about it all first-hand, we applied some none-too-subtle arm-twisting on ‘Artscribe’s co-founder and editor, our longtime collaborator and erstwhile writer-in-residence at Instantloveland, James Faure Walker; and he has kindly responded with Remembering ‘Artscribe’. In it, he chronicles the period of his editorship, and the reactions (and over-reactions) that the magazine’s content provoked; reading it, it’s hard not to conclude that Remembering ‘ArtScrap’ might have been a more fitting title, given how often tempers seem to have flared, and litigation threatened. But that would be to misrepresent what ‘Artscribe’ was looking to do; as James is at pains to explain in this essay, the intention was always to play host to the greatest possible number of voices. There were ‘as many sceptics on board as believers, the point being to keep conversations going across the whole range of opinion.’

Now read on…

One

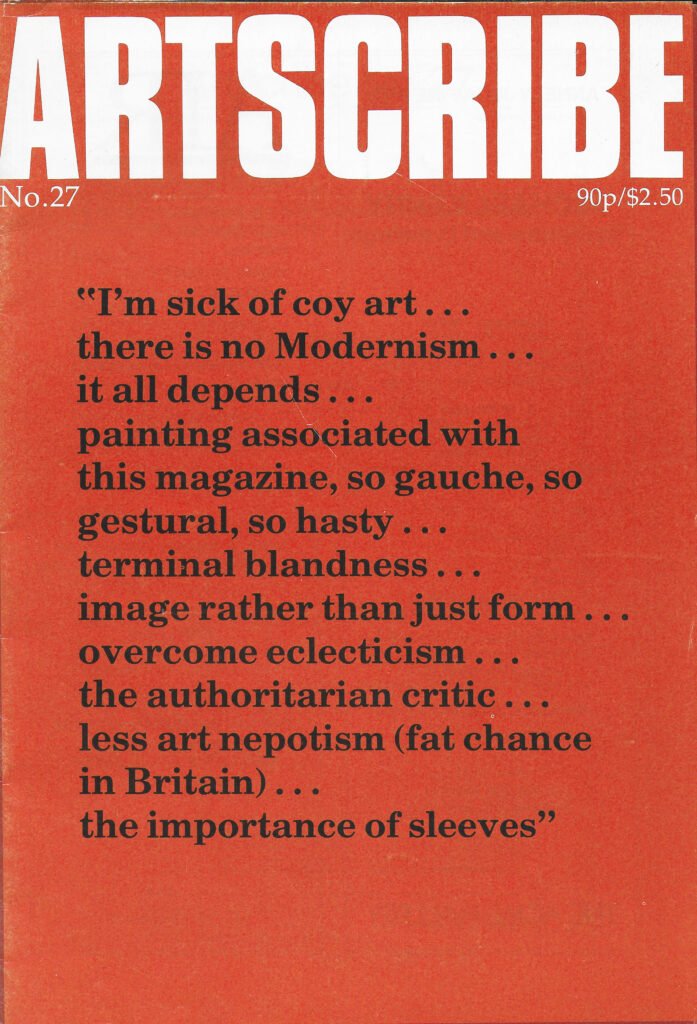

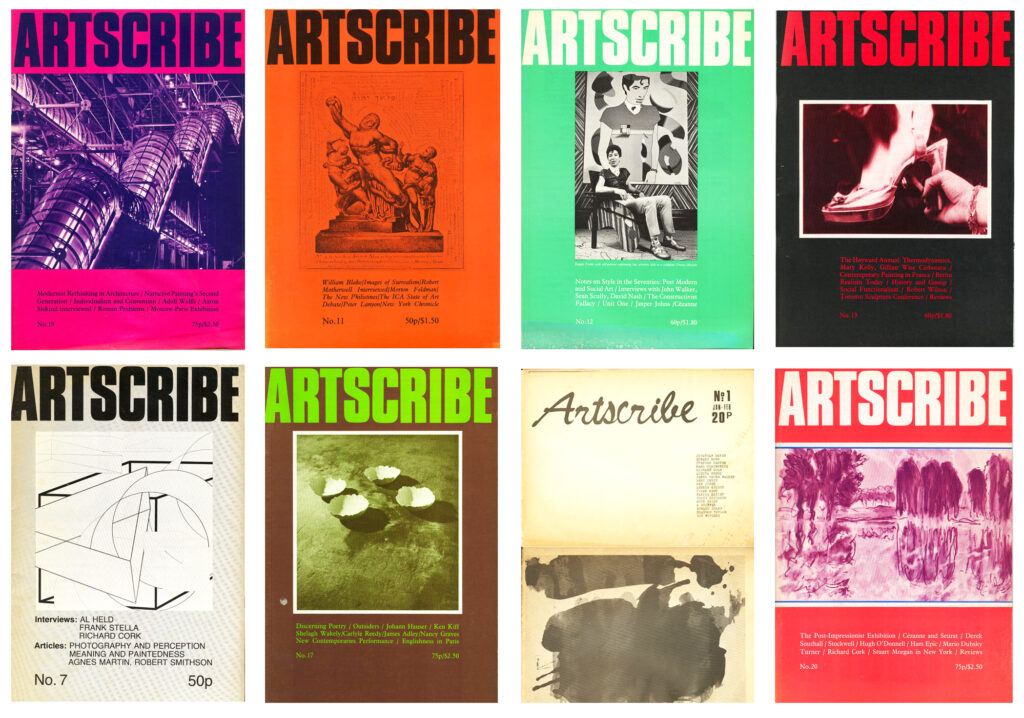

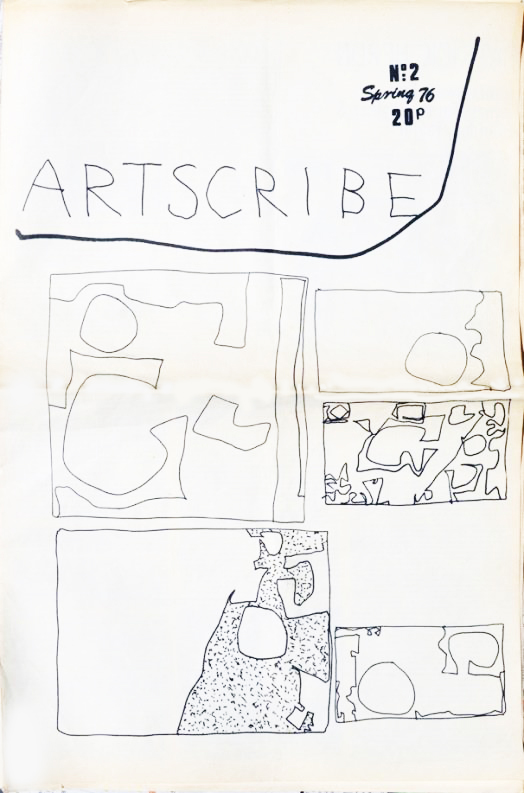

How did a small artist-run magazine with a scrappy newspaper format, selling for 20p, come to such prominence that for a while it was the UK’s main art magazine? Early editions from 1976 sell online for a hundred times their original cover price1See https://www.abebooks.co.uk/book-search/title/artscribe/first-edition/. I was one of the founders in 1976, and then from 1977 to 1983 I was the editor. After that there were four different editors. It folded in 1992. What I have to say here concerns the period I knew: formative years for many of us, a lively period, full of clashing ideas, and one or two episodes that are worth revisiting, if only just to remind us how we got to where we are now2I have described my own perspective on this period in an essay in a recent online catalogue, ‘Works in Progress, Extracts from a Catalogue: Thoughts on Five Decades of Painting’. The relevant sections: ‘Abstract Painting Besieged’, ‘Conceptual Art’, ‘Origins of Artscribe’, ‘The ICA Conference’, ‘The Hayward Annual’. See: https://issuu.com/felixandspear/docs/james_faure_walker_works_in_progress_catalogue_?fr=sMjUzMDM4OTkwNDA.

The story began in 1974, with ‘studio forums’ initiated by Ben Jones: a handful of artists meeting in each other’s studios. Ben had a SPACE studio next to St Pancras Station – that site is now the British Library. I had been working since 1971 in a SPACE studio in Martello Street, E8. We met through a mutual friend, the sculptor Roger Bates (sadly, he died this year). I had been writing for ‘Studio International’, but my submissions were no longer getting published. Even a review of two major Patrick Heron shows didn’t get through. Under the new editor, Richard Cork (previously the Evening Standard critic) ‘Studio’ was now aligned solely with conceptual art and its offshoots.

‘Studio’ had been faltering for a while, with heavy debts, colour plates upside-down and mixed about. The pages had been full of Joseph Kosuth and hard-line conceptual artists3For a detailed account of how ‘Studio’ became dominated by conceptual artists such as Kosuth, see ‘Studio International’ magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1396004/2/Melvin_thesis_without_figures.pdf. It is wrong to blame Cork for the magazine’s collapse in 1979. His redesign was a necessary economy measure, but left it text-heavy: black and white photo ‘documentation’, an ‘intellectual’ look and a correspondingly academic use of language. The passive tense was preferred to the colloquial. I recall ‘quite something’ being changed to ‘it was notable’.

Pronouncing ‘The Death of Painting’ in order to engineer something new has long been a way of getting attention. In the seventies this was the groupthink of a new wave of critics. Abstract painting was the scapegoat, the obsolete and empty art form, fabricated under the spell of Greenberg. The radical opinions of these critics were voiced in newspaper columns and journals, and in Arts Council committees, and soon a string of major exhibitions was to follow, at the Hayward, Serpentine, Whitechapel, British Council; they promoted the New Art, a dematerialised art going ‘beyond’ the art of mere objects. This was fair enough, but it meant no survey shows of painting, and this caused some puzzlement. A season or two later there was a rethink: forget ‘cutting-edge’ art forms, now it was to be ‘Social Art’. Artists were told to make art with a social purpose: art was in crisis, and only a people’s art could come to the rescue. The enemy was again ‘Modernism’, especially the version that emanated from the USA. All this divisive talk split the art world4The polemics about the social functions of art persisted for some time. My contribution to the debate was ‘The Claims of Social Art’, Artscribe 12, 1978, with an update in 2018. Both can be found at: www.jamesfaurewalker.com/the-claims-of-social-art-forty-years-on-james-faure-walker-2018.html. Some questioned why the revolution was led by those at the top. Was it the trickle-down method? ‘Studio’s cover price was £2, not 20p5Today’s equivalents would be around £14 and £1.40 respectively.. Readers stayed away, unconvinced; art school libraries cancelled their subscriptions to it.

We ran an interview with Richard Cork in 1978. He made clear he was not against painting as such, and that at that time he no longer thought painting was ‘stagnant’. However…

Looking through ‘Studio’ one gets the impression that you feel that painting is an inherently inferior type of practice.

RC: No. I deliberately avoided doing a painting issue because I wanted to make a polemical point against what painters say about their own medium. Many of them believe that it is some kind of pinnacle which automatically rides above the range of alternatives which are now open. My plea would not be for any one medium to take precedence over any other, but for them all to take equal parts. Simply because the art of the past has gone into the painting vehicle, and has produced great works of art, it doesn’t mean that painting itself has been responsible for that. If by rapping the hegemony of painting over the knuckles I’ve helped to further that aim, I’d be very happy.

This way of speaking was of its time: ‘art going into the painting vehicle’ was typical of the imagery of a dematerialised form, as vaporous and insubstantial as a mental event, an ‘idea’.

Some have said it was liberating for painting to be taken off the agenda. If you were younger, eager to get out there and exhibit, well, hard luck. Did painters build up the ‘materiality’ of their surfaces in response? Perhaps. But there was a lot more to it than a reaction against ‘idea art’.

Two

From the sixth issue ‘Artscribe’ was staple-bound in an A4 format. Once the magazine became ‘professional’ and regular, it should have been clear that it stood for ‘pluralism’: it covered photography, performance, architecture, dance, and all genres of painting from Photorealism to angst expressionism to post-modern. For the first few issues we worked as a co-op, with Ben the originator and driving force6Ben Jones, myself, Brandon Taylor, and Caryn Faure Walker were there at the start.. There were hiccups: Bill Tucker’s interview for the third issue was sent by ship rather than plane, and that meant a few weeks delay; the fourth issue, on art education, had the wrong number on the front; the design and typography, which I became responsible for after that, was somewhat homespun.

When it came to that fifth issue, we weren’t sure we could afford to continue. We had been subsidising the printing costs from our own pockets, through part-time teaching. We had made the gesture: the cheap alternative press could make a dent in the art world, and we could leave it at that. I can remember the exact place and moment when I thought it was worth the gamble of going further. Through John Hoyland making the introduction, Ben Jones and myself had lunch in a Chinese restaurant with Leslie Waddington. He ran the major gallery, or galleries, in Cork Street. He offered to help by advertising in the magazine, and that would open the way for advertising from other galleries. We also managed to get an Arts Council grant. In neither case was there pressure for the magazine to go this way or that. Our independence had got us that far, and we weren’t going to throw that away in a hurry. We were no longer just an ‘alternative’ forum, a ‘zine’ on the margins: we were a viable magazine. But only just: we could not afford full colour reproduction, and we owned the magazine ourselves7When I took it over, my flat guaranteed the debts. After 1983 I was relieved to sell the magazine for £1..

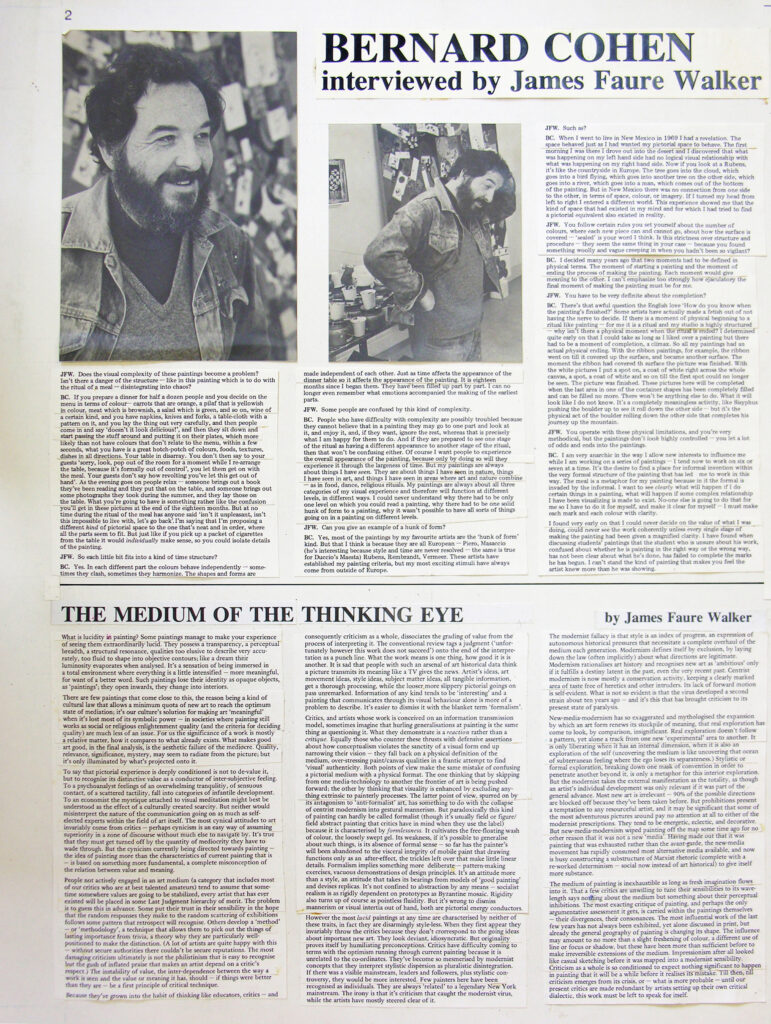

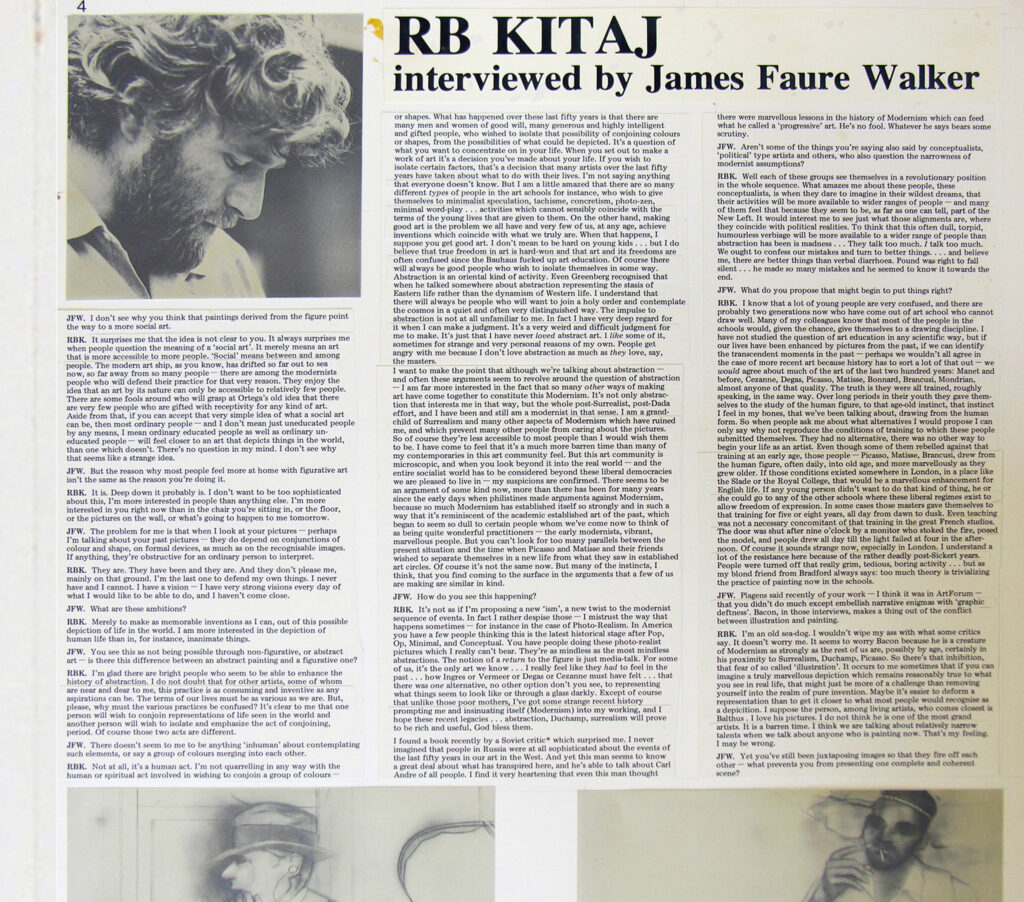

Issue 5 contained the only editorial I wrote. I expressed dismay at the lack of thoughtful writing on painting. I called the essay ‘The Medium of the Thinking Eye’, after Klee. There were two main interviews, with Bernard Cohen and Kitaj; Terence Maloon’s essay on John Hoyland; a conversation with the Stockwell depot painters, who decried the general lack of visual literacy. The next issue, number 6, included a furious response from Peter Fuller, denigrating everything contained in ‘Painting Now’. It was a rant, full of insults, but a selective rant8‘Painting Now’ also contained an enthusiastic pro-Maoist review of a Chinese exhibition by Adrian Rifkin, an article by Andrew Brighton against imperialist American modernism, and essays on David Toop and Susan Hiller.. We were nothing but ‘formalists’, making paintings just for ourselves, art about art, unworthy of serious attention. This is a sample of his view of John Hoyland:

‘Hoyland produces decorative surfaces to adorn the walls of a few wealthy collectors; his work does not transcend the context for which it is intended: outside the art world, and a circle of largely overseas buyers, he is justly unknown. Painting which takes itself as its own subject matter, and content (or which chooses to refer only to contingent areas of experience) cannot expect to attract the attention of those who live in the real world which it excludes. ….I doubt whether even Hoyland has an audience of more than a few dozen individuals outside the narcissistic little puddle of painters, art teachers and students, dealers, collectors and critics.’9‘Artscribe’ 6, April 1977, ‘Peter Fuller responds to Painting Now’, pp. 31- 34. ‘James Faure Walker replies’ pp. 34 – 37.

I responded, point by point, hopefully with some subtlety and decorum. I refuted the gist of his argument, pointing out what I took to be its shortcomings, errors and inconsistencies. Fuller had previously praised Stephen Buckley and Robert Natkin, both ‘abstract’, whom he somehow made out to be the exceptions, and particularly meaningful. He claimed, with typical immodesty, that an expert such as himself was required to ‘reconstitute’ such art for a public betrayed by Modernism. Beneath the posturing, the invective, the ideas were actually facile, even banal. We were just pawns in a conspiracy. Instead of replying to the points I made in my rejoinder he sent a letter threatening legal action, both to Leslie Waddington and myself, on the grounds – quite fictitious – that he had been commissioned to write the essay, and that we hadn’t paid him. We didn’t pay writers at that time, and if we did, why on earth would we have commissioned such a vitriolic piece?10The reality was as follows: he sent in an essay, unsolicited and way too long. We met in his house, round the corner from where I lived, and in a friendly manner agreed how to cut it down. One cut was a passage criticising my own work. I asked where he had seen it, and he said he hadn’t, but he had heard what it was like. I did tell him I would write a response. At that time he was a follower of John Berger. A few years later he switched over to a conservative, ‘Little England’ point of view, founding ‘Modern Painters’ magazine, which would include Prince Charles’ campaign against modern architecture. What had infuriated him was the perceived attack on critics like him, and the fact that we had Waddington galleries taking advertising. He sent the legal threat directly to Waddington, as if we were owned by the gallery, which of course was nonsense. The three of us then had a meeting in Waddington’s office. Leslie was fascinated by Fuller, keen to have a dialogue with an anti-capitalist, and Fuller clearly enjoyed the confrontation, accusing him with some glee of being no more than a dealer, a dealer in cattle perhaps. I was the wallflower, taken aback that Leslie would even think that we had been as stupid as to commission the article and offer money to Fuller. But he agreed to pay a fee, which Fuller – nobly, of course – donated to a North Vietnamese charity. He didn’t want any of this made public, but as the parties concerned are long deceased, I don’t feel under that obligation now. Despite his earlier opinion Fuller actually gave me a pass mark in an ‘Artforum’ review, for the paintings I showed at the Hayward in 1979, and later (after my time) he wrote a few things in ‘Artscribe’.In its first years ‘Artscribe’ claimed that artists had been ill-served by their overseers. Such a haughty reaction, and coming from a would-be Marxist, helped make our case.

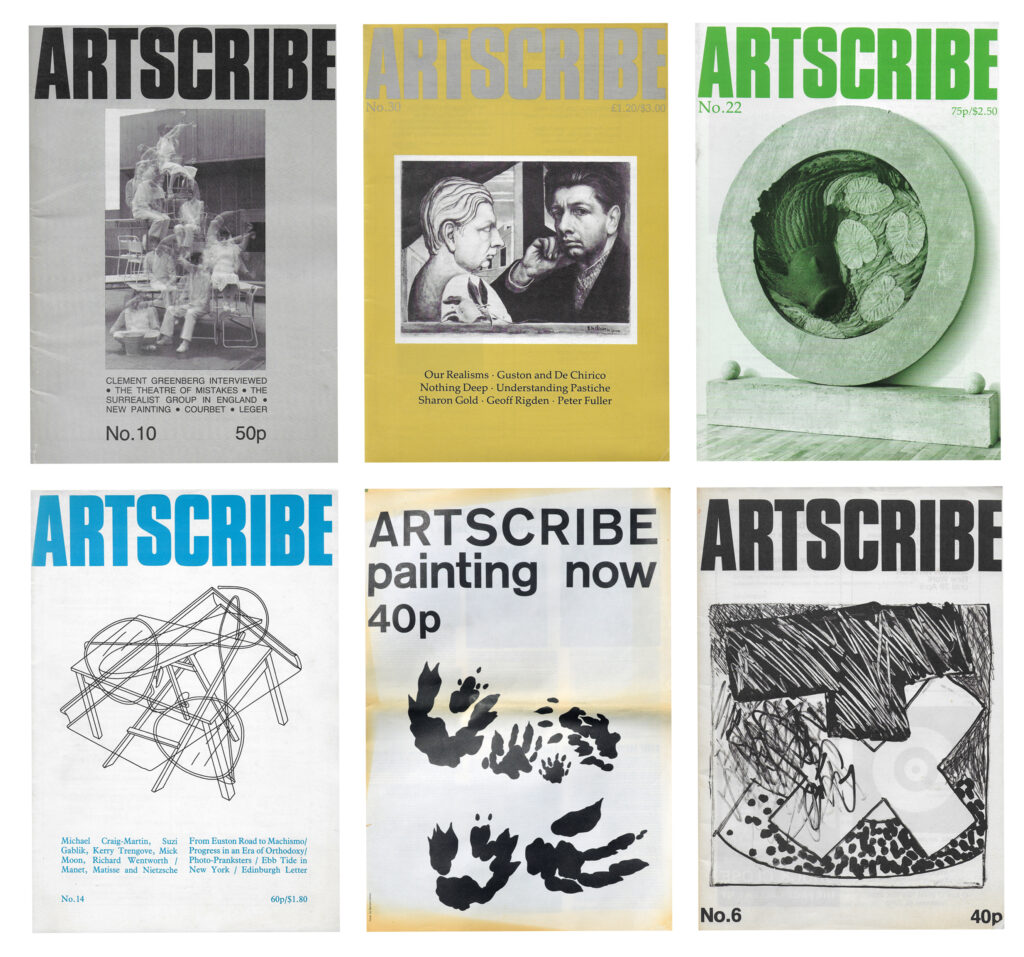

Early on we had regular – and brilliant – essays by Stuart Morgan from New York and Germany, plus contributions from France and India. The dollar sign on the cover, after the tenth issue, was because of strong overseas sales. Did ‘Artscribe’ eventually take over ‘Studio’s role?11I was sorry to see ‘Studio’ decline and disappear. I had been a subscriber since a schoolboy, even appearing in a 1963 issue. Years later I acquired an almost complete collection of ‘Studio’ going back to the 1890’s. They cost me nothing. They were being discarded by a London art school library. I was alerted by a fellow member of the London Group, David Redfern. The anti-glossy aesthetic of its last phase – cheap-looking paper, text-heavy, insider art world talk – became the house-style of ‘Art Monthly’ magazine, started up by Peter Townsend about ten months after ‘Artscribe’. He was the ousted editor of ‘Studio’, well-connected, and presumably he had their subscribers’ list. ‘Studio International’ was ‘liquidated’ in 1979, but after some gaps now has a revived web presence. The extent to which Cork, Fuller and the other organizers of the ‘Crisis in British Art’ were to fall out with each other can be found in the December 1979 issue of Art Monthly: https://www.proquest.com/openview/4d37727d5cfe7a3a83591bf8e70b7c4a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026363 I can’t answer that, but even as a scrappy news-sheet sold at private views, we were buoyed up by the reception we got. I remember David Hockney complimenting a piece on progressive painting – far too long – I wrote for the third issue.

Three

There is a risk in taking extracts from what was published forty years ago out of their context. Essays can lose their urgency and relevance. But in interviews, especially, there are thoughts as alive today as they were back then.

This is from Howard Hodgkin interviewed by Timothy Hyman in 198012Howard Hodgkin interviewed by Timothy Hyman, Hodgkin, ‘Artscribe’ 15, December 1978, p. 27.:

HH: Intimacy is the closest human relationship, the one that everybody shares. But I love parties. To quote Jane Austen, ‘Everything happens at parties’.

TH: Someone like Kitaj seems to feel guilty about his pictures containing irony, about the element of conceit implicit in this.

HH: Yes, but I don’t. I would like to paint pictures that make people laugh.

TH: Why are you so reticent about the sources of your imagery?

HH: Because I think increasingly the less information about pictures and specific elements in them, the better.

TH: But doesn’t that open the way to their being taken as formal arrangements?

HH: That’s a test I think they’ve got to pass. I want them to get there on their own. Richard Morphet produced a whole further chapter of that Serpentine catalogue, which described the subject matter of each of the works reproduced. But I’m afraid I said I’d rather it wasn’t put out. I felt it would become between the pictures and the public.

People can see things in my pictures like they can see things in the tea leaves at the bottom of the cup. But often, although people attribute the wrong part of the painting to the wrong area of subject matter, yet they still apprehend what it’s about. I feel very strongly this relationship should not be disturbed; I feel when I’ve finished a painting that it’s a gesture outwards to everyone else, and I don’t really want anyone to come between.

TH: You’re asking that the subject matter should remain essentially ambiguous?

HH: I would like to paint pictures where people didn’t care what anything was, because they were so enveloped by them. I’m trying to find the maximum emotional intensity, even if the painting’s about a joke, with the minimum of definition.

TH: What do you look for in a painter’s work?

HH: Ultimately, the painter, the temperament. With great painting, you do feel surely that you’re in communication with the person who made it. It’s a paradox, that the more complete the physical object, the nearer you get.

….

TH: Do you have an interest in the future of painting?

HH: I’m not interested really in general ideas about art, because I find it so difficult to produce anything at all anyway. To me that would be just another worry. I can’t understand how programmatic artists work.

The interview that boosted our sales in the USA was with Clement Greenberg, published in the tenth issue in 1978. I had done an interview with him for ‘Studio’ four years earlier, but he hadn’t wanted that published13‘Artscribe’ 10, 1978, Interview with Clement Greenberg. This was republished in ‘Clement Greenberg, Late Writings’, (2007) edited by Robert C. Morgan, University of Minnesota Press..

Here he touched on less familiar topics. The interview took several days, and I felt I got to know his private side. Travelling back with him from one of his lectures in a taxi, he was full of remorse for belittling a member of the audience who had tried to outsmart him about Jasper Johns. You didn’t have to agree, line up with his acolytes, or even disagree. I didn’t tell him I was a painter myself. Re-reading this, I recall what it means to give your all to looking at art, excluding everything else. Perhaps that’s a controversial idea in these times, and others have more pressing priorities. Yet he was never too sure of what he thought: he was always looking, listening, probing.

I asked about American criticism having long had a mission, the feeling that culture was threatened, not so much from outside, but from within. In the thirties was it the threat of Fascism?

CG: Oh no! No one in their right mind was afraid of Fascism in America. It wasn’t political at all. And then it turns out that our ‘Marxism’… it was inherited from the early avant-garde. It was Baudelaire, and Manet – who never took an attitude. It was the notion among a certain group of Frenchmen that culture was under assault from the bourgeoisie. I myself wouldn’t put it that way – the bourgeoisie, the poor bourgeoisie. But that’s part of what called the avant-garde into being, the feeling that standards were being lowered. Manet didn’t think he had any cultural mission when he got fed up with what he called the ‘soups and gravies’ in the painting he saw around him on the 1850’s. There’s a stereotyped attitude that things are going to pot, there are political threats and what not, and you denounce. I used to wallow in it – if you can wallow in a posture – and think: crisis! Crisis! There are threats, and menaces – you wouldn’t have to specify it as Fascism or whatever, just deterioration and so forth.

JFW: When you were one of the editors of Partisan Review, from ’41 to ’43, you wallowed in it then?

CG: Yes, and how. It was one of those received ideas you just went along with, unexamined ideas you grew up with. My early stuff is full of it and I blush when I re-read it.

…

JFW: You believe pure art to be a fiction?

CG: A useful one. It was a useful one, and maybe it’s no longer useful. Not a fiction, an illusion. That was the motive power behind a lot of very good art of the past hundred years. But that I subscribe to the notion of pure art? I should say not. I just don’t know what pure art might mean, except as an illusion, a guiding idea in the Kantian sense: an idea you never achieve, an ideal.

….

JFW: You’re prepared to provide an explanation for bad art in social terms. In other words, bad art is not autonomous, but linked with social causes…

CG: A bad audience, I’d say. An audience that has allowed these things. The audience that takes Duchamp seriously as an artist rather than as a cultural figure – and he is a very serious manifestation, culturally, if not artistic or aesthetic, in my opinion. The audience that would have him be a good artist as well as an important cultural figure, the blame lies there.

JFW: Conversely, if the audience were more alert, more aware of art values rather than cultural values…

CG: Or fashion or whatever. Let’s not dignify the audience too much.

JFW: … that would have an effect on the art being produced?

CG: Of course. It has. My original explanation of what became novelty art had to do with the triumph of the avant-garde, and the fact that it became a popular triumph. So I was leaving social factors out. It was finally in the fifties recognized that most of the best art of the past hundred years had come from the avant-garde, from Modernism. And certain conclusions were drawn by younger artists: that the thing to do was to be far out, because all the great modernists had appeared to be far out when they first came on.

JFW: Back in the days when you wrote as a champion of an unrecognized avant-garde, wouldn’t you have heard those same words spoken by a conservative, claiming the artists were after a new look?

CG: Not the same. It was a thought these people in the sixties had set out deliberately to confirm everything philistines had said about modernist art. I’ve written about that.

JFW: You’ve written of a conventional taste underlying the purveyors of an advanced look. That would be true of the Minimalists, Andre for instance?

CG: Carl Andre simply lacks, as Judd does to a lesser extent, a sense of proportion. I think you can bring off anything in art in principle: square plates on the floor and all that, these could be made to work: it’s conceivable. But Andre doesn’t make them work. When Andre was doing upright, elevated sculpture, you could see the conventional sensibility coming out, and taking resort to module – the brick-like forms laid up, one inverted pyramid on top of another. This guy, with his conventional sensibility, was resorting to something far out, and also had to grab a module to do it. Now someone else could conceivably make something great out of that, driven by different impulses. The far out had become the refuge of people who were conventional to the core. Robert Morris particularly. His sensibility comes into full view when he does those things in felt, that tasteful symmetry, I rather like them as interior decoration, but they’re not much. At heart he has an academic sensibility, and it peeks out, and in order to disguise it you throw boards around, big pieces of steel at random…. Judd’s a different case, he’s flat-footed. But now and then he runs into something. It’s not a question of sensibility. Judd has nothing to hide except a certain obtuseness, which is not as bad as conventionality. And, again, now and then he runs into something.

Four

It was an unwritten rule that we never wrote about our own work in the magazine. But as soon as any of us had our work on show in a gallery, we were easy game for anyone who wanted to take a shot. Some felt it was a mistake to be part of a show that could associate the magazine with a particular style. In 1978 I was one of five artists14The others were John Hilliard, Paul Gopal-Choudhury, Nicholas Pope, and Helen Chadwick. invited by the Arts Council to curate a section of the 1979 Hayward Annual, the major survey at that time, and sure enough my section drew a hail of derision: we couldn’t draw, we weren’t even up to the standard of an art school show15My section consisted of Bill Henderson, Bruce Russell, Gary Wragg, Jenny Durrant and myself..

At the same time Ben Jones had organized a touring show called ‘Style in the Seventies’, named after a feature we were running (beginning with Terence Maloon writing on Duggie Fields and Postmodernism). That show brought together younger painters and sculptors we had featured, including ourselves. Some were to be taken up by galleries, some bought by the Tate16For example the Nicola Jacobs Gallery, Ian Birksted Gallery; Bill Henderson and Jenny Durrant’s paintings were acquired by the Tate.. The reviews in newspapers and rival magazines were airily dismissive. The ‘Art Monthly’ reviewer said he got to the Roundhouse gallery (the London venue) after it closed, but that didn’t matter because it wasn’t worth the bother of actually seeing the works. The Observer reviewer, William Feaver, worked out that the longer the artist’s statement, the worse the work; he called it all too pretty.

Most painters I know are their own most severe critics in their studios, and know their limitations. Some of these reviews made valid observations. But collectively they appeared to reject the very idea of anything new happening in painting. We were upstarts, no-hopers. To visitors from overseas the hostility of the critics confirmed what they took to be the stereotypes of ‘Englishness’: the provincialism of a predominantly literary culture, puritanical, indifferent to the delights of painting, insular, small-minded and afraid of the modern – the willful eccentricity of pixies in the garden, or gloomy, tortured life-painting17I recall Max Kozloff saying he admired Peter Blake on these grounds.. After 1980 there were no further ‘Artscribe’ exhibitions. Soon I was the only surviving member of the original team18Ben Jones had left, Terence Maloon went to Australia, Peter Rippon to New York, and the office – first in Covent Garden then in North Islington – was run by Matt Collings, Adrian Searle, Simon Vaughan Winter, Liz Lydiate, Andrea Hill, Helena Drysdale, John Roberts..

Within the milieu of painting – apparent in New York and Berlin as much as in London – the ground was shifting. In part, it was a younger generation setting out on their own, challenging the stylistic restraints of their predecessors. New labels were necessary – ‘New Image’, ‘Bad Painting’, ‘Neo-Expressionist’, ‘Pattern Painting’. Each in its own way cut across the figurative/abstract divide, discarded conventional taste. Early in 1980 I was in New York. I saw shows that were brashly ‘decorative’, and some were truly outlandish. I had met some of the artists and felt some affinity, which helped: I knew what they were up to. Some works, such as Sandro Chia’s, were disarmingly naïve. I was taken aback, but soon realized this was risky, creative, something to be reckoned with – a baroque fantasy that threw my ideas in the air. In comparison, the abstract painting going on – Sean Scully, Brice Marden – looked orthodox and ordinary. It didn’t have the electricity, the buzz. It was worthy and elegant, classically ‘modernist’, but more the end of something than the beginning. Was I converted to all things postmodern, detached, ironic? I didn’t see it that way, as a choice. I was in New York to see the Clyfford Still retrospective at the Metropolitan, which had its own way of being provocative. The last paintings screamed at you with dissonant pinks and greens. Clyfford Still had been a life-long dissenter. I wrote about these encounters at the time19‘Babylonian Oasis’, ‘Artscribe’ 22, April 1980, ‘Clyfford Still’, ‘Artscribe’ 23, June 1980 (online at https://www.jamesfaurewalker.com/clyfford-still-james-faure-walker-artscribe-23-june-1980.html). Stuart Morgan also saw the Clyfford Still show at the Metropolitan, at a different time. He was sitting on the floor in the gallery, taking notes, when an elderly gentleman came in wearing a long coat. On seeing Stuart, he whispered something to the curator beside him. It was Clyfford Still. He suspected his works were being copied. Stuart was asked to leave the gallery.. Other contributors at ‘Artscribe’ had been pondering these same issues, without really resolving them. Then in 1981 along came ‘The New Spirit in Painting’ at the Royal Academy – an institution not known at that time for setting the pace – and painting became the next official ‘Big Thing’.

I have heard ‘Artscribe’ mentioned as having a hand in the apparent resurgence of painting. It is a flattering thought, but we were responding to what we knew first-hand, from studios and fringe galleries as much as from major shows. Rival magazines took a different view of what we were up to, a less flattering view: the magazine was a platform for our own abstract painting; we were the puppets of dealers, propping up the careers of has-been painters such as Heron, Hoyland, and Hodgkin20In an otherwise excellent piece of research J.J. Charlesworth suggested that our motive in running an interview with Patrick Heron was to help relaunch his career. He suggests that ‘Artscribe’ grew out of Barry Martin’s ‘One’ magazine, and that I suggested a merger, but I have no recollection of that. I knew of ‘One’, but from the start ‘Artscribe’ was a different venture. Barry had organised the Victoria pub meeting in 1974 where painters lobbied the Arts Council to pay more attention to painting. At St Martins I had already produced (with Jon Thompson) ‘Jam’ magazine in 1969. Some of its irreverent spirit persisted in ‘Artscribe’. There were other journals. I liked what I had seen of ‘Art-Rite’ in New York, and through Irving Sandler had copies of ‘Scrap’, by Sidney Geist. (See: https://www.artforum.com/print/198802/sidney-geist-34772). Much later on we did have discussions with ‘Artforum’. If I had any model in mind it would have been the ‘Transition’ of the 1930’s, which I mentioned in my essay on Dubuffet here at Instantloveland (https://instantloveland.com/wp/2020/04/03/james-faure-walker-dubuffet-drawing-and-disorder/). As for the claim that we were no more than an attempt to further the careers of has-been sixties artists (presumably like Kitaj or Hodgkin), well I don’t think we were needed for that. To be fair, Charlesworth only looked at the first four or five issues, and found our lack of enthusiasm for conceptual art reprehensible.. In an alternative universe, perhaps. But that idea – ‘Artscribe’ as a monoculture of ‘modernist’ rectitude fighting off the philistines – did linger, regardless of what the magazine contained. We had as many sceptics on board as believers, the point being to keep conversations going across the whole range of opinion. Magazine covers from 1978 – issues 10 to 15 – feature the Theatre of Mistakes, William Blake, Duggie Fields, Alexis Hunter, Michael Craig-Martin, Bruce Lacey and Jill Bruce. None of those advocated ‘keep-it-painting-flat-and-abstract’ as far as I recall.

The magazine had needed to evolve. Magazines don’t matter as much now as they did then, when there were few alternatives. In comparison with instant opinion sharing online today, there seems to have been more time to read, and to reflect. We talk about art world fashions, and there were fashions in the way of writing. Did ‘Artscribe’ help bring about a more conversational style, inquisitive, here and there entertaining? I hope so. It can still be found in the writings of Stuart Morgan21Stuart Morgan’s essays can be found in two anthologies: ‘What the Butler Saw: Selected Writings by Stuart Morgan’, 1996, Durian Publications; ‘Inclinations, and Further Writings and Interviews by Stuart Morgan’, edited by Ian Hunt, Frieze Publishing, 2007., Terence Maloon, Andrea Hill, Adrian Searle, Matthew Collings, Lynne Cooke, John Roberts, Helena Drysdale, and others. By way of contrast, there were impassioned, didactic pieces by Alan Gouk, Tim Hyman, David Sweet, and even Fuller himself later on. There were guest features by Angela Carter, Doris Saatchi, Edward Lucie-Smith, Nancy Graves, Norman Rosenthal, Sidney Geist and Paul Neagu. Somehow, we all pulled together and survived, and unless my memory deceives me, we kept on good terms throughout.

What were the contributors trying to achieve? Some had clear positions, and saw their role as championing the best art, persuading and steering the reader towards that end. Others were thinking aloud, reflecting, trying to work out what they really felt: sometimes until you sit down and write you don’t know what it is you think. I am probably in that category. I had the great advantage of not only being my own editor, but amidst like-minded colleagues, an impressive bunch, full of curiosity and ambition, most of whom, like me, were simultaneously finding their own way as artists. Some were to become key players in the future. As to whether this magazine was a stepping stone on the way to ‘Frieze’, the YBA’s, the extraordinary expansion of interest – and investment – in contemporary art, I can’t answer that. Matthew Collings and Stuart Morgan were both editors after I left, and along with Adrian Searle, they would have been the people to work out an answer. But at the time we did take soundings.

Five

In 1981 we published a survey. There were two simple questions in the survey:

1. What issues do you consider of particular relevance at the moment?

2. Can you say which artists currently working are the most important?

More than half of the seventy people asked actually responded. I have picked out some fragments from fifteen pages22‘It all Depends’, ‘Artscribe’ No. 27, February 1981, pages 34 to 48.. From today’s vantage point the range of opinion being shared is wide, and some responses show remarkable foresight. Many didn’t answer the second question, but among those that did the most repeated names were de Kooning (seven mentions), Kitaj, Hockney, Ken Kiff, Frank Auerbach, Jennifer Durrant, followed by Guston, Jasper Johns, John Hoyland, Joseph Beuys, Christopher Le Brun23You can’t deduce much from this cross-section. But it is interesting who didn’t show up at the top: no Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Stella, Donald Judd, Malcolm Morley, Andy Warhol, Richard Hamilton, and no Louise Bourgeois, Helen Frankenthaler. Just round the corner were Julian Schnabel, Georg Baselitz, Anselm Keifer, Gerhardt Richter..

Waldemar Januszczak:

‘The sort of painting associated with this magazine, so gauche, so gestural, so hasty, has been born out of reaction (to seventies greys and beiges, to minimalism and conceptualisation) and is therefore fundamentally negative. It has done away with the traditional search for form, for content, for structure, and replaced it with an art that takes all its risks on the canvas rather than in the artist’s mind. The final product will continue to miss rather than hit as long as the artist refuses to prepare adequately for the outcome, refuses to relieve the oppressive burden weighing on the senses.’

Terence Clarke:

‘I’m sick of coy art which is technically compromised. I’m sick of the inarticulate masquerading as feeling. Surely we know by now that if you scratch the surface of the mind out pours a mass of inchoate imagery and distortion, which without structure and the intervention of ‘art’, remains incoherent. I’m thinking of Ken Kiff and John Bellany.’

Stuart Morgan:

‘I believe there is a crisis in British art; it is suffering from terminal blandness, an inability to break through that ‘gentility principle’ Alvarez identified as the bane of British poetry. None of the important artists of the last five years have been British: The re-emergence of older styles – gestural painting or fifties geometric abstraction, for example – is possible only if some degree of irony is present… Critics are ignoring new media….The impossibility of formulating an overall theory of art based on anything but decisions about conservative forms of painting and sculpture may force them to back down, specialise, suspend value-judgements, and write only about things that give them pleasure.’

Jeff Nuttall:

‘If a school of creativity appears to be flowering it does so because it has attracted the talents of visionary and competent individuals. If a school, a direction, or an ‘ism’ appears to have dried up this is not because it was always inherently a cul-de-sac. It may, of course, at some time in the future. Minimalism, for instance, is not necessarily dead merely because it became the shelter area of creative cowards.’

Stuart Brisley:

‘The Arts Council is non-democratic and represents the interests of the well-heeled: it continues to re-affirm its adherence to the dominant ideology of the classes in power. In doing so it represents a singular obstruction to progressive art practice and social development.’

Alexis Hunter:

‘To shut yourself up alone voluntarily in a studio for years is not exactly ‘normal’ behaviour (most people do not like to be alone that much if they can help it) and to exploit other people to that end under the guise of artistic martyrdom shows a rather warped sense of communication. You neglect the people nearest to you to communicate to people who you will never meet. These contradictions are most apparent for artists who wish to work around social issues, where they must be aware of the reality of society, to know and understand it, but also need to isolate themselves from it to be able to work.’

Tony Caro:

‘Twenty years ago the question that was ripe for discussion was: how to win full expressiveness for sculpture. To attain this there was no choice for sculptors but to work abstractly. It was necessary to be absolutely clear, and this meant honing sculpture right down to essentials, to first principles.’

Brendan Prendeville:

‘There has recently been an abundance of prescriptive, authoritarian criticism…. The writers I particularly have in mind are Peter Fuller and Alan Gouk. In their different ways, they are both concerned to prescribe for practice, and their strength lies in this…. But authoritarian criticism is self-defeating: it produces a climate of dogmatism, and so, far from overcoming pluralism, it stimulates the development of distinct, sharply-defined genres.’24Alan Gouk’s essay in ‘Artscribe’ No. 30, ‘Peter Fuller, Critic?’, pp. 41 to 49, is among the best pieces of critical writing published anywhere. Whatever else, Peter Fuller’s prominence can be credited with provoking responses way above his own level. Of course, I accept I am biased in saying this.

Len Green:

‘In the seventies the Walkers, Hoylands, Caros etc. were making some extraordinary pieces of work. Today, however, painters and sculptors seem to be doing variations of these artists’ work….When that influence becomes imitation we surely move into a manneristic phase and construct for ourselves an invisible ‘academicism’ based on contemporary taste.’

John Roberts:

‘Hoyland’s mainstream is Modernism’s ancient regime in bright new clothing. Fuller’s expressionist mainstream is nothing more than an updated Morrisesque nostalgia for a lost humanism – arty-crafty with buckets of emotion. Both are no help. Both resist the claims of new media in the name of Art History. If Postmodernism means anything… it means resisting Art History and the pull of ‘historically necessary’ forms. It means getting a fresh line on technology and the experimental forms it has spawned; getting technology to speak a less ‘deconstructed’ language.’

The then-recent 1980 Hayward Annual selected by John Hoyland was mentioned several times. Matthew Collings had reviewed it in Issue 25, in a perceptive piece, well worth re-reading: ‘Overcooked’. He described much of the work as ‘essentially familiar, easy-going, ordinary, frank, honest, boring abstract art’25‘Artscribe’ No. 25, October 1980, page 42..

Six

Whatever was achieved in these years, some credit must go to the art school culture of the time; we had an advantage over previous generations: we were pragmatists, hands-on, encouraged to believe that anything was possible, well prepared for a pluralist, open and diverse art world. SPACE studios had been set up by Bridget Riley and Peter Sedgley in 1968; there were the AIR and Acme Galleries (which also provided housing), and Vera Russell’s Artists’ Market; alternative spaces such as Matts Gallery, parallel journals such as ‘Aspects’, ‘Artery’ and ‘Camerawork’. Artists built their own artworlds, despite circumstances, sometimes with help from the Arts Council. It took some work, and some imagination. The process of getting a publication from idea to print was not as straightforward as posting an opinion on Facebook. It is easy to overlook how much was involved in producing a magazine, yet alone one that came out regularly, looked professional, was informative, and was clearly written26You had to have someone answering the phone, dealing with the post, all the time, so eventually we needed an office. There were no mobile phones, no email. In studios there were shared pay-phones, some of which would only receive incoming calls because they were repeatedly robbed. The only way of receiving copy was in person or by mail. Everything was on paper, typed, needing to be corrected, and edited by hand. It would then be set – photo-setting had just come in – ready for print. The ‘galleys’ needed to be proofed – no spell-checker. Each photo – only black and white – had to be re-sized, its percentage reduction worked out to fit within the text – my first calculator was a Spectrum. For the paste-up we used Cow Gum, on customised A4 sheets with blue tramlines – blue didn’t register in the process. Then to the printers – a car journey, not just press ‘send’. Several days later the double-page spreads were sent to the ‘finishers’ in Dalston. When we picked up the bundles of ‘Artscribe’, we might find our covers placed on top of piles of hard-core porn – such as ‘Bound to Please’ – as a disguise, in the event of a police raid. Distribution meant going round galleries and bookshops, dropping off ten here, fifty there, and mailing out to subscribers. Magazines going to the USA went to the docks, inland in Plaistow. To ensure they actually made it into the containers the dockers would ask whether we were short of reading material, and offer a copy of ‘Horse and Hound’ for an exorbitant fee. That was the deal for access to the container..

Perhaps some periods need to be misremembered. If you only went by what was written in the newspapers at the time, or in much of the art press, and looked at what has been shown since in museum surveys, you might get an impression of a more grey, downbeat and uniform art world than the one I have described here. Before the 1980 Hayward Annual opened John Hoyland reflected on this series, comparing it with Bryan Robertson’s ‘New Generation’ shows at the Whitechapel in the sixties, which had launched a swathe of new artists, including himself.

‘Looking back at the Hayward Annuals, I think that on the whole they have been rather unfairly dealt with. For some reason, some English death-wish for art, the kind of criticism they have received has been quite out of proportion. Almost all the shows have been very interesting, by any standards. The first Hayward Annual, looking back on it, was quite a considerable thing … what an interesting, diverse show that was; there were so many good things in it, and it had cold water poured all over it by almost everybody … It’s funny how people get history all wrong. The ‘New Generation’ shows were similarly reviewed in their time. Well, maybe the same thing will happen with the Hayward Annuals in about ten years’ time. People will say, yes, that’s so and so, it was a very important exhibition. It’s almost always too early to say, but you’ve got to give people confidence.’27‘John Hoyland and the Hayward Annual’, interviewed by James Faure Walker, Artscribe No. 24, August 1980, page 39. In the following issue, No. 25, there was a letter from Bryan Robertson, gently disagreeing with Hoyland’s remark about the ‘New Generation’ shows. With Hoyland’s ‘assembly of paintings’ in mind, Robertson implies he never believed in stylistic uniformity: ‘The ‘New Generation’ shows cut right across stylistic barriers, at a time when fixed didactic positions were being increasingly enforced, but also provided a sharply focussed survey of their stylistic range. This kind of definition was and still is rare.’ He goes on: ‘The ‘New Generation’ shows of 1964, 1965 were seen in the light of a policy established at Whitechapel from 1953 on, which presented work by British artists at the same level as work by distinguished foreign artists, or historical exhibitions. That is, the quality and content of the catalogues and documentation, the attention paid to presentation in terms of lighting, space, publicity, and so on was at the same level as the resources deployed for foreign art. Until then, modern British art had never been treated in this way.’

When I left ‘Artscribe’ in 1983 it was a wrench: I was abandoning something I had helped to build up, which by then exerted considerable influence. I had been an artist-in-residence in Australia. I could say I found the Great Barrier Reef a more interesting ecosystem than the Art World. True. I was also exhausted – eight years of holding the balance between getting on with my own painting, writing, editing, with the responsibility of shaping the content to meet the deadline every two months. It was grating to spend time over the work of some artists too lazy even to provide proper measurements for their paintings, paintings which, whatever the reviewer thought, I might well find unremarkable. I never set out to be a magazine editor, or an art critic. Trying to make paintings – as Howard Hodgkin remarked – is difficult enough as it is.

11 thoughts on “James Faure Walker: Remembering ‘Artscribe’”

The hatred of Hoyland and Caro is growing, if anything, as my tweet re Hoyland’s show at Canary Wharf proves. I was away in New York for the entire 1980s and missed much of this vitriol. Thank Goodness. After the room full of drunks at Fred Pollock’s show, and the negative reception to 1980s Hoyland, it all came back to me what a truly unsympathetic cultural environment there is here for art. How many readers have taken the trouble to go to Dulwich to see Frankenthaler’s show? Still the same writers/broadcasters using their career-making abilities to call the shots. Most of them couldn’t wield a brush if you asked them. Let alone decide what makes a picture worth looking at.

Patrick, perhaps you were drunk at Fred Pollock’s opening?

I saw no drunks there at all, in fact the Gallery were being rather careful in filling

glasses. Half of the visitors seemed to be from Fred’s extended family and young.

Maybe you were mistaking those lively youngsters for how we used to carry on, all tanked up and full of shit.

Cheer up Patrick! Try to ignore that old, bitter and twisted Twitter feed for a moment and look at things another way. Hoyland is getting much more positive airplay these days on many fronts. The Hoyland estate is in partnership with Hales Gallery. Hales have made revitalising the careers of older, mature artists their speciality, and with the articulate and charasmatic Matthew Collings fronting the PR campaign things are looking positvely rosy. Great work is being done behind the scenes too by younger art historians such as Sam Cornish, who is rethinking Hoyland and British Modernism in general. New audiences are being drawn into the complex history of post-war British modernist art ( into which James’ excellent article on ‘Artscribe’ gives us another fascinating insight). We have had major outings of Hoyland’s later works in his home town of Sheffield and in London’s financial heart, Canary Wharf. There is also a beautiful new book on the later work which has been incredibly well received internationally. Onward and upward Patrick! Onward and upward…

Many thanks Jim for all your work as editor of ‘Artscribe’. The magazine provided a welcome and accessible platform not only for reviews and interviews but for intellectually ambitious ‘long-form’ art criticism, often written by practitioners, seriously engaging with the challenges of contemporary visual art.

Again: thanks

It was like waiting for a bus. And then John Clark, and David Sweet came around the corner at the same time. Art as plain generosity. D

Thank you John. There are two shows I would love to see this week, yours and Georges Braque’s! Robin, Stephen and my show closes this weekend, the majority of visitors other artists. Meanwhile the RA Summer show has been described as weak, although everybody wants to be an artist, Matt Collings and Andrew Marr included. I haven’t seen the RA show so shouldn’t comment, but the ‘Artscribe’ memoirs brought back exactly the waves of grubby nostalgia that sent me to live in NY. These attitudes, plus Thatcher, The Falklands, Orgreave, the miners fighting to work. Now we have Trump and Johnson, the RA book and scarf shop. Where are the revolutionary youth? On Instagram? I remember Bob Dylan’s rage triggered a new movement and political climate. Is it too much to ask young artists to give up endless self-promotion, try another form of genuine expression, and undermine the status quo? Rage, rage, at the dying of the light! Just looking for my bus pass, I know it’s here somewhere! Best, Patrick

This was such an interesting and reflective account. I also share concerns about the insularity of the British (or should that be English?) art world. There seems to be a widespread denigration of the ‘abstract’ and Hodgkin’s remarks on this are very relevant to the continuing question of how ‘abstract’ paintings are made, received and understood. I think that in this country we are scared of any visual experience that cannot be immediately explained and classified. Oddly, the notion of musical abstraction is readily accepted as a vehicle for imaginative musings but not its visual counterpart. This whole conundrum is one result of a hopelessly outmoded educational system which views all of the arts with suspicion, not least the visual arts. There is an irony in that it is only in the well-resourced private schools that art departments are likely to flourish and that until the provision for the arts is ‘levelled up’ in all schools and across a wider spectrum of society, the prevailing philstinism surrounding visual arts will undoubtedly continue.

Exactly Michael. My daughter is in a failing school, with poor funding, has no art class! I’m afraid James has flagged up the importance/impotence of critics, journalists etc, who don’t actually practise,j ust pontificate.The artist on his own in his studio is viewed with suspicion.

Well that was educational, thanks for putting it up. Between 1967-71 I read ‘Studio’ and enjoyed it immensely, having been referred to it by one of my college tutors. I discovered Pat Heron through it but I was also working hard in film, TV graphics and animation while making my own painting, which had continued after I left college but petered out. I really lost all contact with the art world until 1985 when I got going again, then stopped again in 1998 for more graphics until I at last resumed painting in 2013 and will now continue as an abstract painter until I drop. But maybe that experience of commercial work and other media has given me a different perspective. I paint now because it’s what I enjoy doing. I create something permanent, or relatively so. Unlike animation it doesn’t whiz by in a few minutes or seconds, never to be seen again. Unlike printed material it doesn’t go in the bin as soon as it’s read.

I think abstract painting can, and indeed has to, exist at many levels. It can be just what it is, paint on a support, a formal arrangement of colour and shape, gestural or grid-based, it can be decorative (what’s wrong with that? it’s still a useful function, if not essential) but, much like a piece of music is basically a formal arrangement of sounds, notes, meant to achieve rhythm, harmony, melody etc. it can also carry meaning, a reference, a feeling or an idea even though that might be difficult to explain. And does the artist need to explain it? If the painting hits the viewer in the right spot that they can feel maybe explanation is unnecessary, but perhaps it should be available if required. The interview with Howard Hodgkin above said it all.

I am part of a studio group which is very mixed, all kinds of painters, sculptors and conceptual artists, some fresh out of Uni. We have to respect each others’ work even if we don’t like it. Artists are voted in by a majority vote. Some work with political content which I see as propaganda; I’m sure many see my abstract painting as irrelevant and old-fashioned.

Now that I’m 73 and a late starter as an abstract painter I have definitely missed the boat, I really should have kept going in 1967 but it’s probably too late now. However, this article has filled some gaps for me. Thank you, if I had know about ‘Artscribe’ at the time I would have subscribed and might have kept going

To respond to John Bunker, carefully, as all these people mentioned are my personal friends: the first person I bumped into at Hoyland’s was Gary Wragg. We showed together at MOMA Oxford in 1971. We discussed the problems of preserving our estates. These are not castles, but hundreds of canvasses, mostly very big. As for my friends Sam Cornish and Matthew Collings, I wouldn’t wish the future of English Painting on either of them, as it’s a huge responsibility. My problem is, I can remember a time when a painting wasn’t something to fill a gap above the fireplace, but hinted at a new world order. Of all the quotes in James’s article, I warmed to Stuart Brisley. I had too many evenings with Clem, because we could lock the door of his office, drink and smoke. He was wonderfull about Pollock, Hofmann, David Smith, but despite his fondness for Olitski, the game was over. So my question is, where will the new initiatives come from ,and my answer has to be from the artists, John Bunker, Robin Greenwood, James himself. It is great to see Fred Pollock and Frank Bowling getting some acknowledgement at last. We are dependent on youth, like Stephen Walker and Lucy Jagger to find a way through the myriad of distractions on offer, masquerading as Art. With more leisure time, the middle class will all have studios at the bottom of the garden. I felt a twinge of nostalgia from the photos of The Hayward Annual, Jenny Durrant’s extraordinary works. Even if we were picked up by mega-galleries, sold at Christie’s for obscene sums, would the art get any better? That isn’t my yardstick. Probably should be painting under bridges in a hoodie, with a spray can! Very best, and thanks to James for his reflections. Was the obnoxious Peter Fuller a closet Marxist?

Just wanted to wish John, Matt, James, Sam some wonderful holidays.You have certainly cheered the world up enormously with your essays. Engaging, perceptive, fascinating! Where would we be without you? As Alexis Hunter says, we would be alone in our garrets! Very Best, Patrick Jones