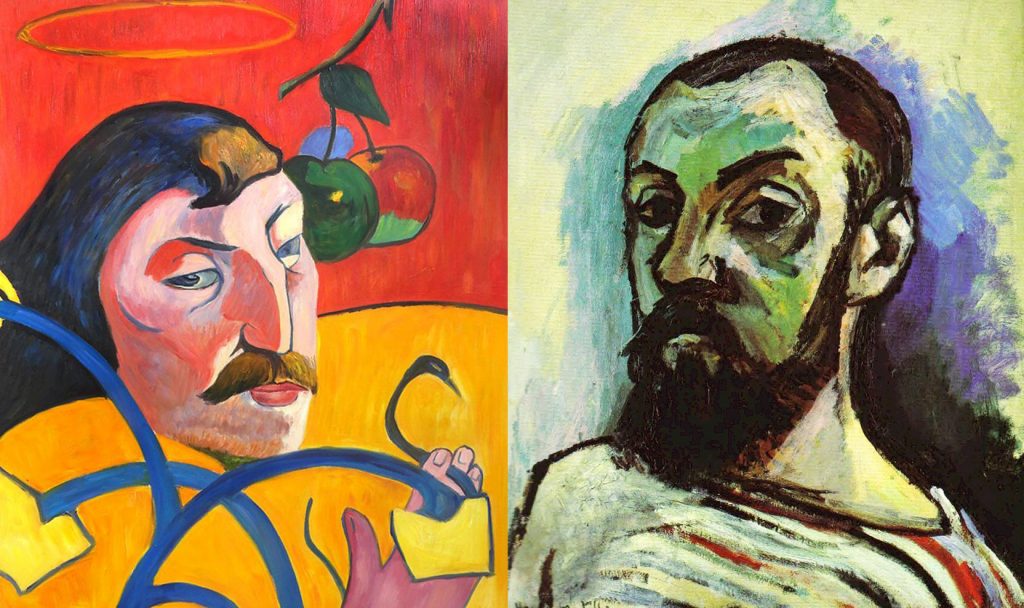

Alan Gouk: ‘Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, Part II: The Apotheosis of Decoration’

In the second part of his extended essay, Alan Gouk examines how the ornamental impulse in Gauguin’s late paintings finds its full expression in the breathtaking decorative splendour of Matisse…

There is much that could be applied to Gauguin in T.S. Eliot’s brilliant and highly personal essay on Baudelaire:

‘(He) is concerned, not with demons, black masses, and romantic blasphemy, but with the real problem of good and evil …. to a mind observant of the post-Voltaire France, … a mind which saw the world of Napoleon le petit more lucidly than did that of Victor Hugo …. the recognition of the reality of Sin is a New Life; and the possibility of damnation is so immense a relief … that damnation itself is an immediate form of salvation — of a salvation from the ennui of modern life, because it at last gives some significance to living…. It is apparently sin in the Swinburnian1Algernon Charles Swinburne is considered a poet of the Decadent movement, with its predilection for excess, who sought notoriety through risqué subject matter. He was supreme as a stylist, of style over substance. According to Oscar Wilde, Swinburne ‘was a braggart in matters of vice, who had done everything he could to convince his fellow citizens of his homosexuality and bestiality without being in the slightest degree a homosexual or a bestialiser.’ He did however ‘like to be flogged’. Eliot admired his critical writings on Shakespeare, but was averse to the flamboyant touting of deviances. Gauguin, on the other hand, went to great lengths in his paintings to disguise his paedophilia by dressing it up as hints of evil portents.sense, but really sin in the permanent Christian sense, that occupies the mind of Baudelaire.’

But unfortunately it is doubtful whether Gauguin’s sense of sin is deeply felt on a personal level. It is sin in the Swinburnian sense that preoccupies him. Considered purely in terms of their symbolism, Gauguin’s paintings are pretty small beer: opaque, impenetrable, indecipherable. Compared to almost any poem by Baudelaire or Mallarmé, selected at random, they are obscure and vague, suffused with a mute suggestiveness which consists largely of moody glances and sinister expressions. Gauguin’s declaration, ‘I intend to become increasingly incomprehensible’, is surely not something that Mallarmé would have said, even allowing for the cult of mystery the poet advocated. The mark of a satisfactory poem is articulacy, lucidity, a self-sufficient reflexive clarity in the sequence of symbols which surface within its structure. The grammatical, syntactical and narrative disjunctions which create obscurity in Mallarmé are offset by a circular, self-reflexive richness of reference unmatched by anything in Gauguin up until his chef-d’oeuvre, ‘Where Do We Come From…?’ We have to wait until Picasso for grammatical and syntactical disjunction.

‘Soyez Mysterieuses’, as an injunction, is oxymoronic. To try to cultivate ‘mystery’ on purpose is to solicit vagueness as a positive, and whatever else Mallarmé’s powers may be, they are not vague. It is Baudelaire’s imagery to which Gauguin most aspires, in attempting to create a visual equivalent; and especially the exotic longings of Baudelaire’s early poems, ‘Exotic Perfume’, or ‘The Sick Muse’. But to quote from one example, here is part of ‘The Beacons’ of 1855:

‘Rubens, a river of oblivion, a garden of idleness, a pillow of cool human flesh on which we cannot love, but where life endlessly tides and heaves like the air into the sky, and the sea with the sea:

Leonardo, a fathomless dark glass in which exquisite angels, their tender smile fraught with mystery, are glimpsed in the shade of the glaciers and pines that guard the frontiers of their domain:

Rembrandt, drab hospital that echoes whispered woes, furnished with naught but a vast crucifix, where a weeping prayer sighs from the filth, and suddenly pierced by a winter sun:

Michaelangelo, a no-man’s-land where we see Hercules and Christ together, and rising stark upright, powerful phantoms who in the twilight rend their burial shrouds and stretch their fingers long:

Puget, with a boxer’s fury and a faun’s salacity, who could exalt the beauty of the scum of the earth; that great heart swollen with pride, that sickly jaundiced man, Puget the sullen emperor of jailbirds:

Watteau, that carnival in which so many illustrious hearts wander incandescent like butterflies, in cool and frivolous settings where chandeliers pour down the garish light of madness on the swirling dance:

Goya, that nightmare haunted by the unknown, foetuses roasted at witches’ sabbaths, old hags peering into their looking-glasses, un-nubile girls all naked but for their stockings which they stretch tight to tempt demons:

Delacroix, that lake of blood haunted by evil angels, with its dark fringe of fir-trees evergreen, where under a glowering sky strange fanfares can be heard, like Weber’s muted sigh:…’ (Translated by Francis Scarfe).

But how Gauguin would have liked to have seen his name added to their list, and how one would like to know what Baudelaire would have made of him!2

And

here is Mallarmé, on Baudelaire :

The buried temple divulges through the

sepulchral Mouth of a sewer drooling mud and rubies

Abominably some Anubis idol

Its whole muzzle aflame like a wild bark.

Or the recent gas twists the squint-eyed

wick which has been submitted to countless insults

And illuminates terrified an immortal pubic

bone

Whose flight moves from lamp-post to

lamp-post.

What dried leaves in the cities without

votive Night will bless the shade as it

sits down

Vainly against the marble of Baudelaire

In the fluttering veil which covers it absent

For it is a protective poison

To be breathed in even if we perish from it.

(Translated by Wallace Fowlie).

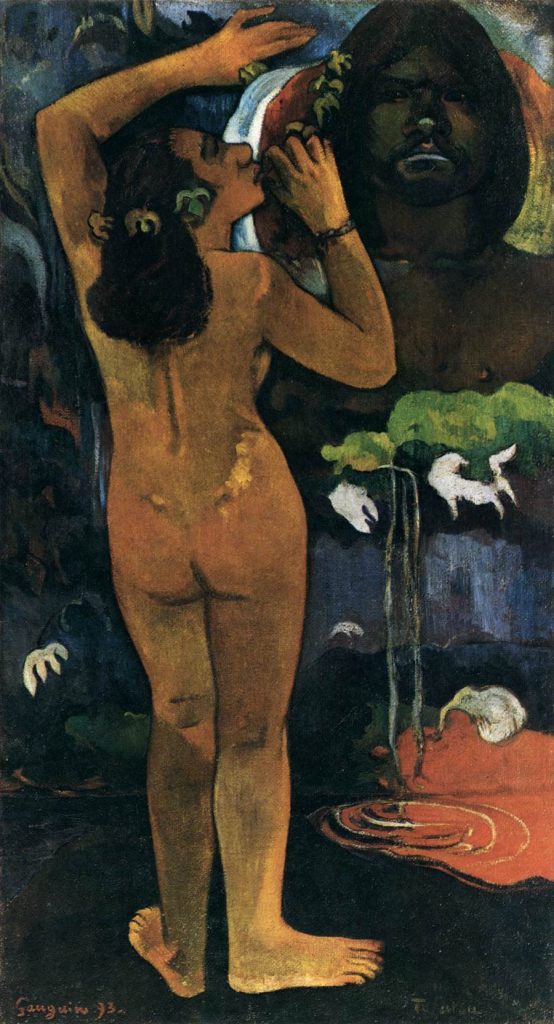

For a self-advertising ‘savage’, ‘wolf’, seducer and practiced libertine, Gauguin shows remarkable reticence, if not exactly prudery, when portraying the female body. He is at pains to avoid the accusation of ‘indecency’, perhaps in deference to the authorities, both Catholic and civic, on Tahiti. His gaze is never lecherous, his poses unabashed but never wanton. In the portrayal of his Tahitian ‘Eves’, the sex is never visible, only the Mound of Venus; the thighs are pressed close together in concealment, even in poses where this would have been near impossible to achieve; and similarly when seen from the rear, the buttocks are primly held in, with not an indication of a gap between them, the delineation and shading tentative and suppressed with minimal dehaunchement of narrow androgynous hips, in accordance with the overall sinuousness of the tubular body contour which Gauguin has derived from East-Asian sculptural reliefs. Not for him the exposure of Courbet’s ‘The Origin of the World’.

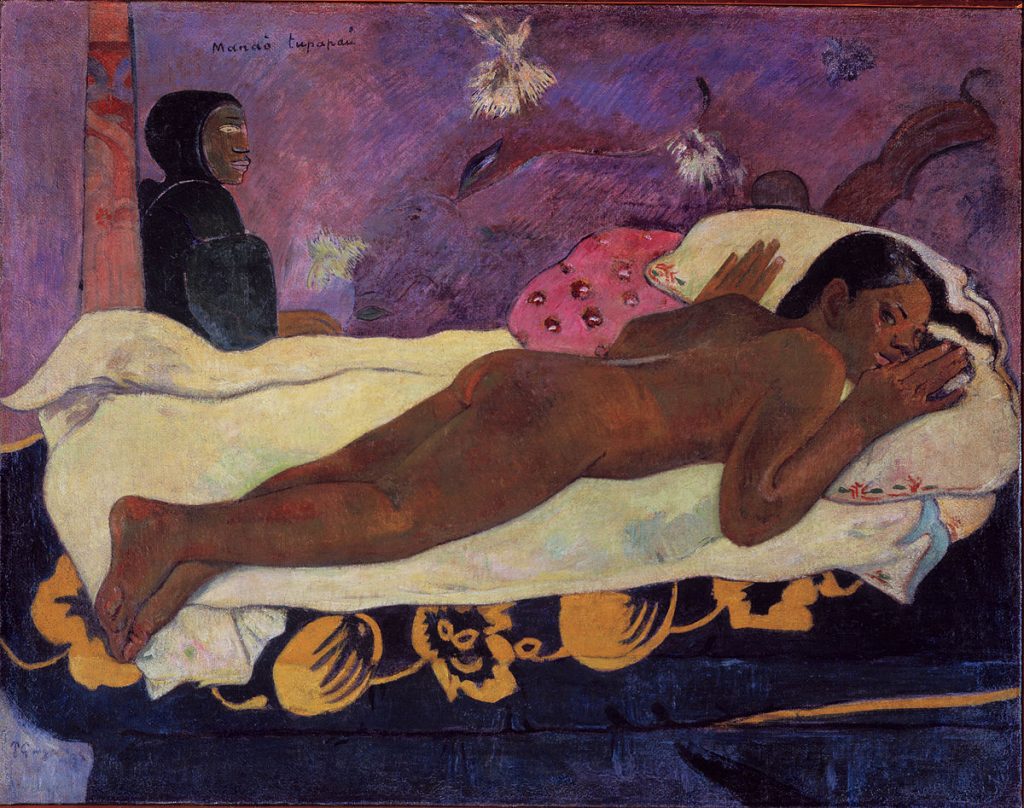

There is, however, a suggestive confessional element. He avowedly wished us to recognise himself in the sinister ‘Malin’ overseer in the background of ‘Manao Tupapau’, the implication of deflowering being rhymingly hinted at; and there is the indecorous drama being played out in the decorative setting of ‘Parau na te Varaua Ino (Words of the Devil)’ of 1892, in the National Gallery in Washington, in which a frightened young girl holds a cloth to her vaginal area, concealing but at the same time drawing attention to some invasive importunity or worse, implying defiling, ravaging, or some perverse forbidden sexual practice.3A paradox: if Tahiti is such an earthly paradise, why is it full of evil portents and indices of Christian guilt? It seems that Gauguin is projecting a double psychology: the image of a life free of prohibitions, but an image in which his own guilt is projected onto his girl subjects. It is harder to escape the European heritage of shame and repression than he would like to think. Or else his symbolism is simply bogus. There is much to be said about all this, but not by me. It needs a cultural historian of wide knowledge.

What is the ‘sin’, we are asked to ponder, since neither Gauguin nor Tahitian society considered sex itself sinful between men and young girls. Gauguin does, however, reveal (but only in ‘Noa Noa’,4First published in 1897, an idealised and embroidered account of elemental life in a Tahiti of Gauguin’s imaginings, and the origins of some of his most powerful images, but bearing only a tangential relation to reality.never in the paintings themselves in regard to which ‘Noa Noa’ stands as a tittilatory commentary) that he considers sex with men a ‘crime’ (if an intoxicating one), ‘the awakening of evil’, ‘the desire for the unknown’, and that he ‘alone carried the burden of an evil thought’. Nancy Mowll Mathews unequivocally states, but without giving her approval, that ‘By writing Noa Noa, Gauguin, more than any other artist of his generation, shaped the concept of the modern artist: original art is that which has been created by an original person’,5Mowll Matthews, N., ‘Gauguin – An Erotic Life’ p197thus elevating the cult of personality (albeit one constructed by a propagandist and fabulist, out of lies, deceit and the appropriation of the discoveries of others) above all other considerations. After Vincent’s death in 1890, Gauguin began to take credit for his friend’s style, claiming to have taught him. In life Gauguin’s behaviour was becoming monstrous, that of a scoundrel, one of the bad boys, malins, poêtes maudits, of art.

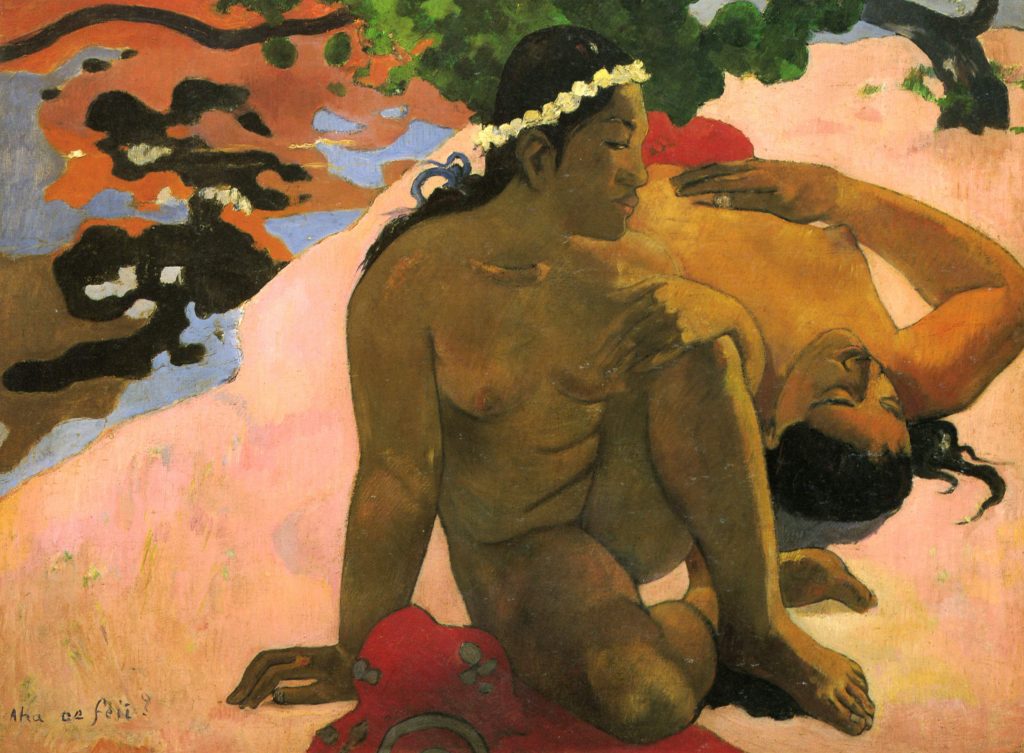

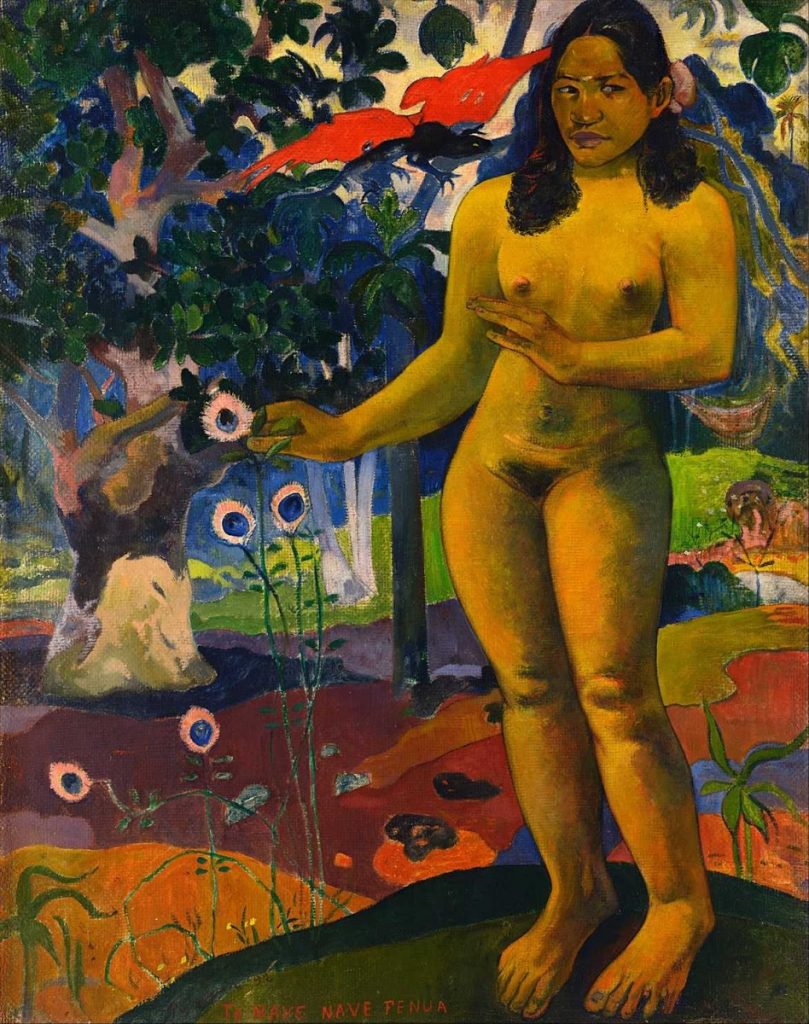

And yet, and yet… Whatever the causes, whether from erotic fantasy, the reality of his erotic ventures in Tahiti, or a melding of both, his art takes a giant leap forward during the first sojourn on Tahiti. There is no question that he worked hard at his paintings (and carvings), as he had always done, to simplify and harmonise, the ardour and arduousness of his engagement reaping rewards in a new monumental simplicity in the disposition of his models, many of whom fill the canvas from top to bottom in close-up; ‘Woman with a Mango’ of 1892 (Baltimore, Cone Coll.) being one of the finest of the early Tahitian pictures, where his modelling of the features does justice to the undoubted beauty of his sitters, though beauty in itself is not his primary aim. It is not an erotic fantasy of exotic beauty which he creates, but a genuine response to a beauty which exists, but which he darkens in mood, allowing the whole decorative scheme of the picture to express something languid, rich and strange (as Matisse would later claim of his own approach to expression), at least in these full height studies unburdened by overt symbolic intent: ‘Two Tahitian Women’ of 1899 (Metropolitan Museum) from his second Tahitian period, ‘What, are You Jealous?’ of 1892 (Pushkin Museum), and, if we ignore the ominous black lizard half concealed in the foliage, ‘The Delightful Land’ of 1892 (Okayama).

The symmetrical, sculpturesque features of his subjects arouse in him a manner of drawing surer and more original than he had ever achieved before, and the modelling of their (admittedly schematised) columnar volumes, which imitates Far Eastern and Indian sculptural relief, is restrained in its shading (the contre-jour shading in ‘What, are You Jealous?’ being particularly impressive), thus allowing the limbs of the women to dovetail with the surrounding areas, which are never just flat pattern, but are also shaded with hatching strokes tying the whole image together at the surface. His touch both in modelling the figures and in the banded decoration of their setting is solid, emphatic yet nuanced, enabling greater continuity across the entire surface of the picture. Indeed, if there is any 19th century artist to whom the continuity of the canvas weave is an aesthetic imperative, it is Gauguin; it is one of the principle unifying features of his later style, to which the future of painting owed so much.

And the decorative, ornamental schematisation of trees, foliage and landscapes, the vertical rhythm of tree trunks enriched by curving branches and fanning sprays of leaves and blossoms enables an Oriental, ‘Persian’ splendour of colour, Gauguin being one of the first to reference the decorative qualities of Persian and Indian art as an influence.6 See also my article, ‘The Gypsy’, 2016

Derain, Matisse, Bonnard, Braque and many another would follow his lead, and this, the most radical strain of innovation in 20th century painting, is an insinuating refrain which springs from the art of Gauguin at his best and continues to confound the arguments put forward by the likes of David Sylvester right up to today.7David Sylvester, à propos of Patrick Heron’s Tate Britain retrospective in 1998, puts into the mouth of an anonymous female friend (not having the courage to say it himself) the sentence ‘Decoration- I suppose that’s just about the most damning thing you could say about a piece of art’, thereby revealing just how out of touch with the true and main current of modern art the British really were, and remain.Of course there is decoration and decoration, and Gauguin’s pictures are so much more than just decoration. It was Tahiti, and the erotic charge it lent to Gauguin’s imaginative reverie, whatever that reverie may have entailed in practice, that gave the impetus to his pictures, and redeems the narrative betises which beset them. Love (which Gauguin never knew), eroticism, and the libidinous flow of an imaginative life, these are the life-blood of genuine art, and even if the first of these terms was absent, enough remains to give the later Gauguin a momentous place in the story of modern art.

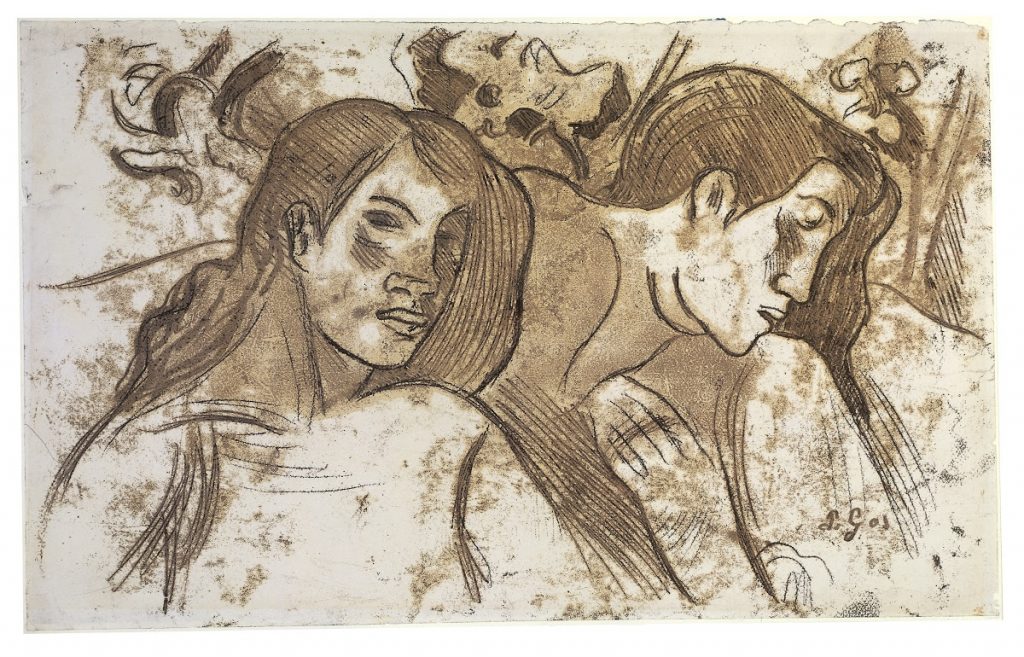

In his greatest works, the olive and bronze skinned ‘Vahines’ and ‘Eves’ take their place in an overall decorative schema without obtrusiveness, a genuine chordal nicety offset by stronger contrasts of more saturated hues from their pareus (loincloths) and broad zones of blue, yellow, pink and violet. ‘The Bathers’ of 1897 (Washington) is a particularly felicitous example, where the olive-skinned bodies merge with the overall scheme without undue sculpturesque prominence, a fusion both of his colouristic skill and his, by now, mastery of drawing and modelling (see the drawing ‘Tahitian Faces’ of 1899, in the Metropolitan Museum), a fusion which Matisse would also master by the time of the reclining Odalisques of his Nice period.

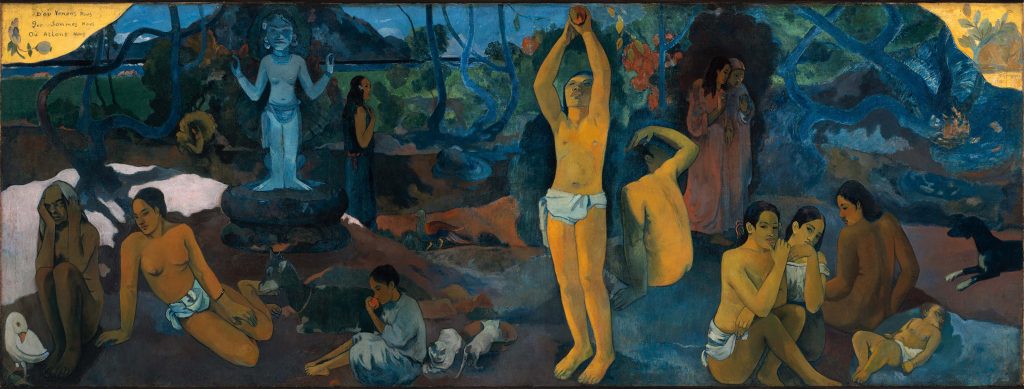

It remains to discuss the late masterpiece from his second sojourn in Tahiti, from 1895 to 1901: ‘Where do we come from, Who are we, Where are we going?’

Dissonance in painting, strident contrasts of colour, only count in the context of an overall harmony, and in this the subtlest of arts, Gauguin became something of a master.8Charles Rosen, in his marvellous book ‘The Classical Style’, writes: ‘Expression is a word that tends to corrupt thought, Applied to art, it is only a necessary metaphor. Accepted as legal tender, it often gives aid and comfort to those who are more interested in the artist’s personality than in his work. None the less, the concept of expression, even in its most naive form, is essential to an understanding of late 18th century art’. However, in his book in defense of Schoenberg, he arrives at a quantitative theory of expression; since dissonance is the expressive carrier in music, and since Schoenberg is the most dissonant composer, he is ipso facto the most expressive. Leaving aside the context of consonance, this will certainly not do for painting. In the later Tahitian pictures, dissonance of colour is hard to find, and for the most part absent too are the jarring insertions of narrative detail which mar the Breton pictures, and some Tahitian ones too, such as ‘Delicious Mystery’ of 1894, ‘Te Poi Poi (Morning)’ of 1892 in which a Tahitian woman appears to be at her latrine, and ‘Are You Waiting for a Letter?’ of 1899.

It is the mellow harmony of relatively subdued colour, built up in layers, neither strident nor over-assertive, that gives Gauguin’s best pictures their spellbinding quality. As I have said, he worked harder to achieve it than he made out he did. Almost everything of aesthetic power in Gauguin comes from his colour, and though the later paintings are more sombre and dark in overall tonality than before, this is rather a sign of harmonic subtlety and maturity, rather than a reflection of the desolation that he must have felt at his plight (in terms of both his health and his career). And the fact that one tends to reach for musical metaphor in discussing them is a vindication in itself, given that Gauguin set such store by analogies between colour and music.

There are of course many bad pictures from this period too, which reprise some of his favourite provocations in contrived and hackneyed juxtapositions. Even the much maligned Meijer de Haan makes a reappearance as a claw-fingered troll. The Marquesan pictures9The Marquesas Islands were more remote and cheaper to live in. Gauguin was forced to move there after falling out with the authorities in Tahiti due to his belligerence. He felt he had exhausted Tahiti as a source of inspiration, but his difficulties would only mount as he provoked both the Catholic hierarchy and the Gendarmerie on the small volcanic reef, only twenty-five miles across.are often a falling-off from the high standard of Tahiti, and are frequently more blatantly contrived in their imagery, its placement rehashing old themes without inspiration. This is surprising, since in his graphic work he seems to be attaining a new level of voluptuous boldness in drawing; but when he tries to replicate the achievement in his painting, the results are slack, irresolute and fatigued.

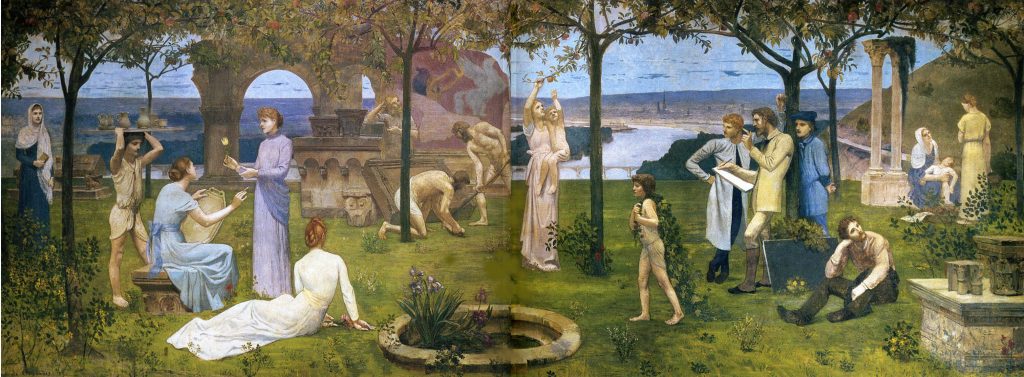

The influence of Puvis has been played down by Gauguin’s advocates in deference to the latter’s propagandising in support of his own originality. The theme of wrestling nude boys which had exercised Gauguin at Pont Aven in 1888, a prelude to the inclusion of Jacob wrestling with the angel in ‘Vision after the Sermon’ of 1888, is foreshadowed in Puvis’ ‘Pleasant Land’ 1882 (Yale). The sort of decorative trees that appear in it would come to play a prominent role in several of Gauguin’s masterpieces, ‘Hail, Mary’ of 1891-92 (Metropolitan Museum), and ‘The Noble Woman’ of 1896 (Pushkin Museum).

Just as ‘Where do we come from…’ is a summation of Gauguin’s major themes, Puvis’s ‘Between Nature and Art’ of 1888-91 (Rouen) plays the same role in the latter’s art. Could Gauguin have seen it on his way to Pont Aven in 1890? Doubtful. He must have heard descriptions of it, though, because the similarities between the two works are surely more than coincidental.10

First,

the Puvis picture: the rhythm of tall tree trunks with overarching branches

divides the picture into three main asymmetrical segments. A central figure,

child held in one arm, (like a Picasso of the 1920’s), reaches to pluck an apple

from an overhanging branch (an image of classical antiquity, without

Judaeo-Christian implication) To her right, a group of three young artists

ponder the imponderables of nature versus art; a fourth is seated gazing

outwards towards some potted plants (their species unclear, but no doubt

intended symbolically).

The

three, (the picture is composed of groups of three, with one or two pendants)

are looking across to a group of three muses, poetesses, one holding a flower,

one lying with her back to us, and a Grecian youth carrying a tray above his

head, caryatid-like, with some pitchers on it.

To

left of centre, two athletic semi-nude males attempt to lever a gravestone into

position; behind them, a clad female figure with arm raised is holding her

hair.

To

the right of the central figure, there is a young girl with long hair, in

profile, walking to the left and carrying a braid of ivy or laurel leaves. In

the middle distance, there is a ruined classical temple, with a mural on a

shadowed wall showing a painting of winged Pegasus escaping his handler.

To the extreme right, outside the rhythm of trees, there is a hooded figure cradling a sick companion, and a female companion, beside another classical ruin (a pair of Corinthian columns) and at the extreme left, a shawl hooded female observer. A mysterious column capital in stone rests on the ground with carving suggesting a face.

In ‘Where do we come from…?’ the central figure plucking a mango reaches from top to bottom of the picture, and a child, seated , eats the fruit. To her right, three Tahitian women seated, the foremost coming as near to revealing her sex as any figure in Gauguin (in place of the three muses), and a young girl lying on her back. At the extreme left, in place of the pensive seated artist, a crouching woman, head cradled in her hands, one ear half covered (hear no evil?) and another beside her sits facing outwards.

In place of the striding young girl with long hair in profile, a darkly clothed woman, also in profile, with long dark hair. In place of the seated muse with her back towards us, a seated nude with arm raised above shoulder height, hand to head. In the middle distance, two women surrounded by a cowling, in rapt, brooding conversation; instead of the classical ruins, the statue of an idol, (Hindu?) illuminated in blue. To its left a little nymphet in a shell. In place of the athletic nude men, two very sketchy bathing figures in a distant pool. There are sundry animals, a goat, cats, a dog, a bird, in the Gauguin- none in the Puvis.

The rhyming branches, vertical in Puvis, snake and curl throughout the broad open spaces of the Gauguin picture, ornamental yet tying the whole picture together as a decorative unity, without the staged progression of layered distance that beset earlier pictures, ‘The Day of God’ of 1894 (Chicago) or ‘Sacred Spring’ of 1894 (Hermitage, St. Petersburg), where the transitions in scale from foreground to middle-distance to background are conventionally rendered in picture postcard naïve, or faux-naïve.

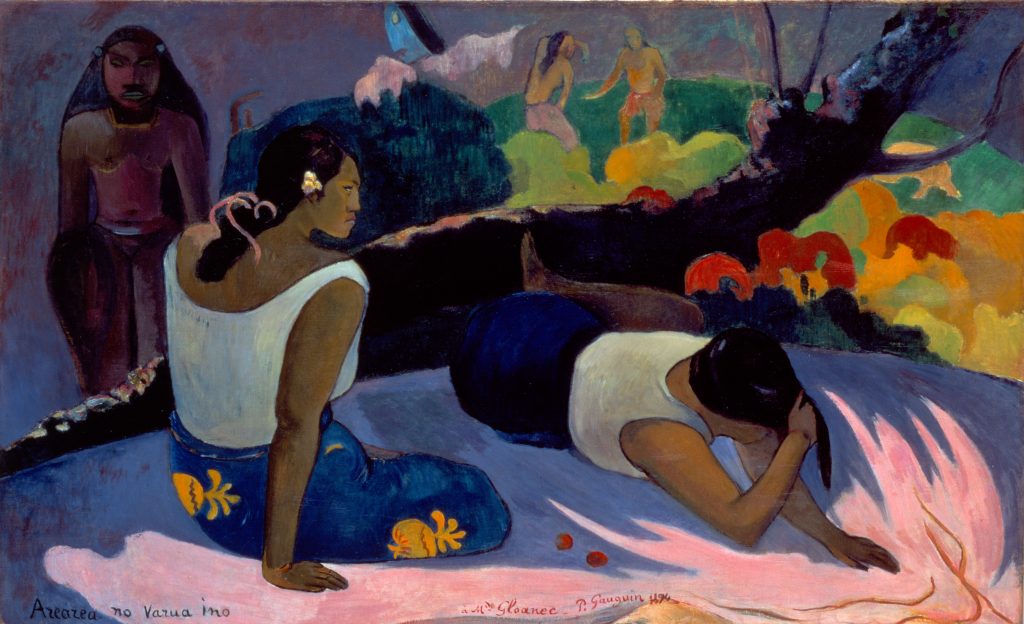

In contrast, ‘Where do we come from..?’ uses the surface-hugging patterning of colour of ‘Arearea no Varua ino, or Reclining Tahitian Women’ of 1894, in Copenhagen; and yet, because of the breadth of conception of the whole tableau (which had been carefully prepared in a smaller drawing and transferred to the large canvas by scaling up, in contradiction to the artist’s mythical account of the painting’s origins) there is a lateral openness to the design which conveys a sense of space. Gauguin’s by now masterful technique, ‘very flexible, very fugitive’ is able to accommodate an irrational space, part dream landscape presented as real, in which figures come and go, out of scale with any believable perspective, yet seemingly relaxedly right (not something that could always be said of his work).

Starting from the feet of the central figure in ‘Where do we come from…?’, in relatively continuous raking perspective, there weaves a diagonal mound which recedes all the way to the left edge of the picture, grouping together three of the foreground seated figures, and on which the idol is set, on a stone plinth or pond reminiscent of the one that is centrally placed in the foreground of the Puvis picture. Across this mound falls a shaft of pinkish-cream light; and in defiance of rationality (because there is no unified light source in the picture) dark shadows of branches are cast. Several figures seem to be illuminated from below, as in a son et lumière tableau, this executed with great skill. The rest of the landscape spreads laterally from behind this mound to a vanishing point outside the picture, opening up broad vistas of mangrove swamp, lagoon and mountainous island at some distance, and yet forming a continuous plane, like a painted stage curtain, closer and more phantasmagorical on the right of the picture, where the bathing figures frolic in a shady pool.

Looking to the left, the transitions in depth are relaxedly continuous; to the right, more abrupt and unrealistic, with a suggestion of steeper perspective, and the hooded cowling of the two conspiratorial women interrupts any continuous reading of the spaces.

It is an achievement almost on a different level to anything he had done before: a summation, but also a trumping of any of his past attempts to situate his figures in imagined space. The two yellow intrusions at the top corners which break up the potentially illusory space are important both colouristically and in the way they emphasise the flat patterning of the design. Without them, the figures might almost be set in a continuous illusionistic space. With them, the complex arabesque of snaking tree trunks, shadows and interwoven areas of ground come to the fore, and the interplay of earth colours and gold and violet body tones, set against blues and greens of the ‘background’, allows the major sequence of contrasts which create the harmonic architecture of the picture to reveal itself.

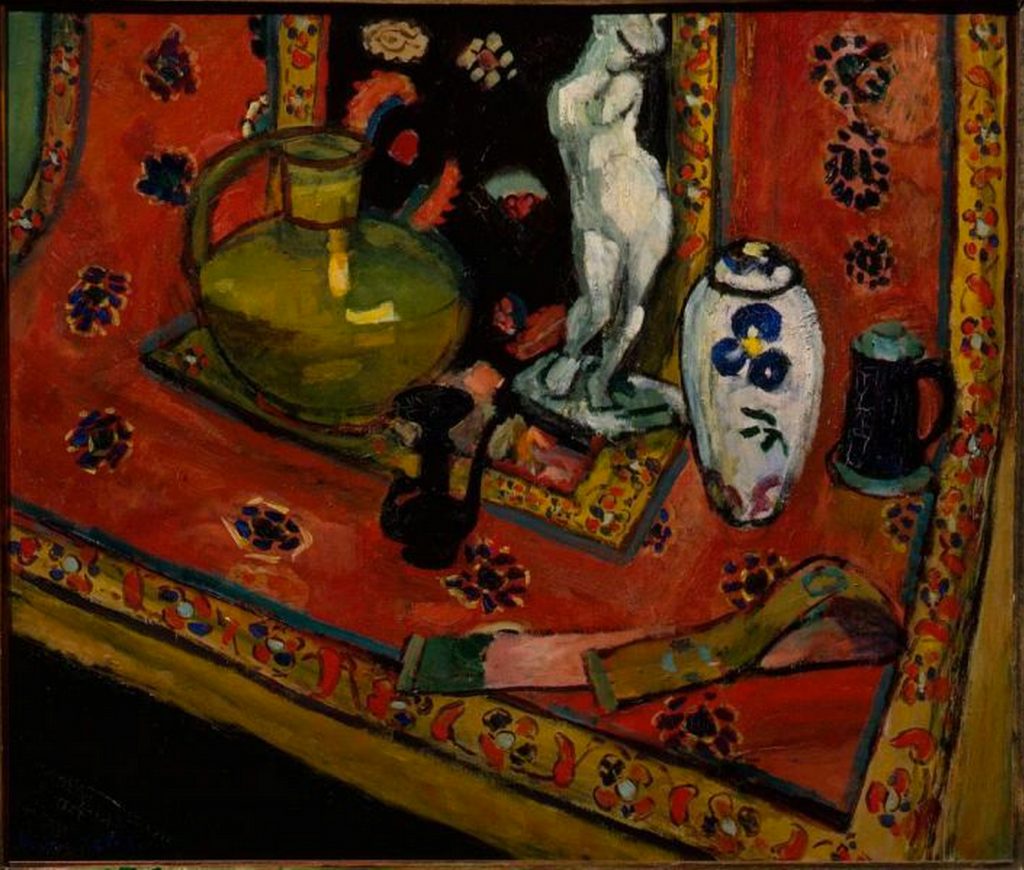

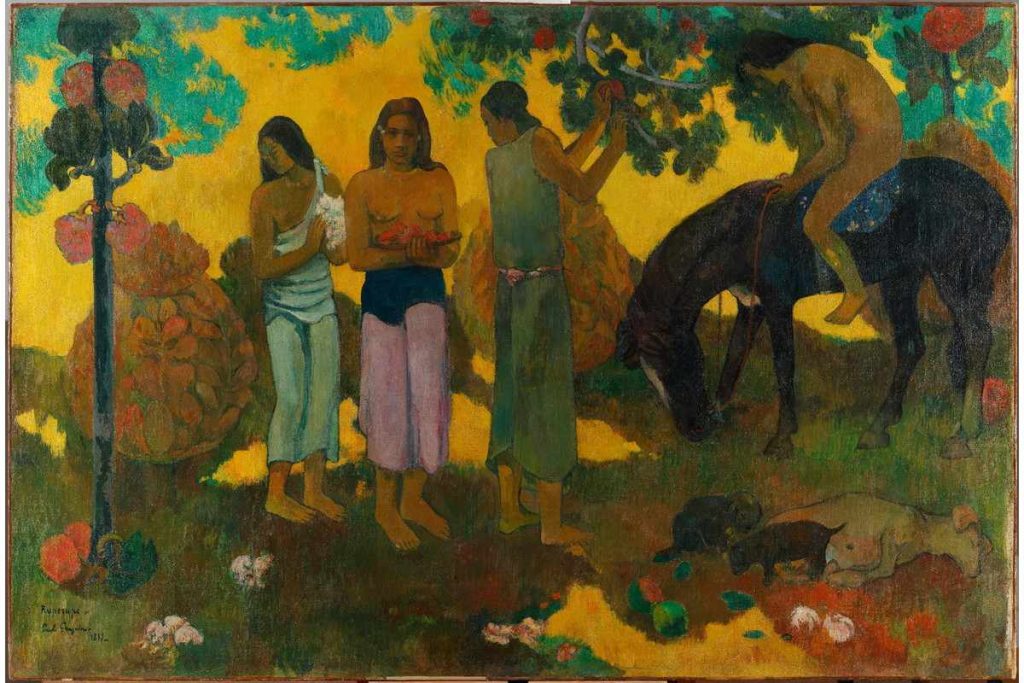

In November 1911 Henri Matisse made a trip to St. Petersburg and Moscow to see Schuhkin and Morozov, two of the principal collectors of his work. In Moscow he was able to see his own paintings, ‘Luxembourg Gardens’ of 1901, ‘Statuette and Vase on an Oriental Carpet’ of 1908, and ‘La Desserte’ of 1908, alongside two major Gauguin canvasses, ‘What, Are you Jealous?’ of 1892, and ‘Gathering Fruit’ of 1899; and he was no doubt reminded of the influence Gauguin had exerted on him during the ‘L’Age D’Or’ episode of 1904-06, in which he projected a romantic image of a mythical paradise of Luxe, Calme et Volupté (and Bonheur de Vivre). The problem of situating volumetrically modelled figures in a decorative setting addressed in these Gauguin paintings would preoccupy Matisse for the rest of his life.11I was first made aware of the debt Matisse owed to Gauguin by a remark of Prof. John Golding in The New York Review of Books in 1985: ‘… it was Matisse more than any other artist who saw through to its ultimate conclusion the greatest lesson that Gauguin had to teach, that it was possible to be a decorative artist and still remain within the avant-garde, or more strongly and more appositely, that it was possible to be a decorative painter, and simultaneously to be a high artist, even a revolutionary one.’

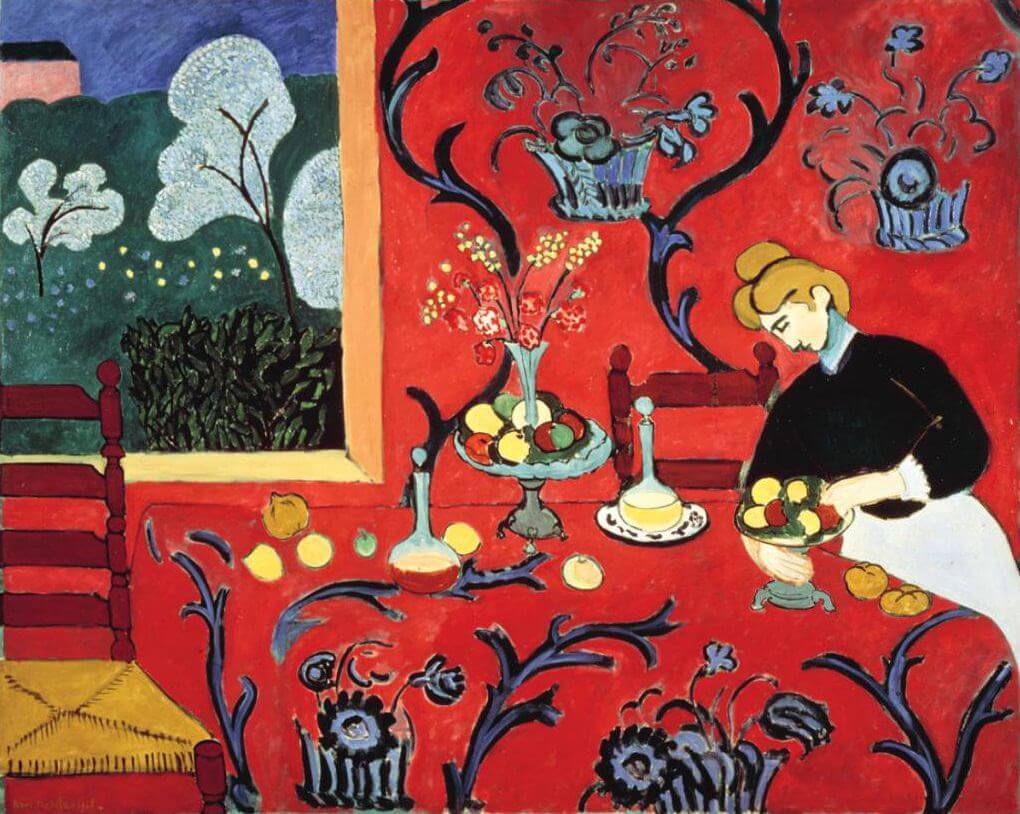

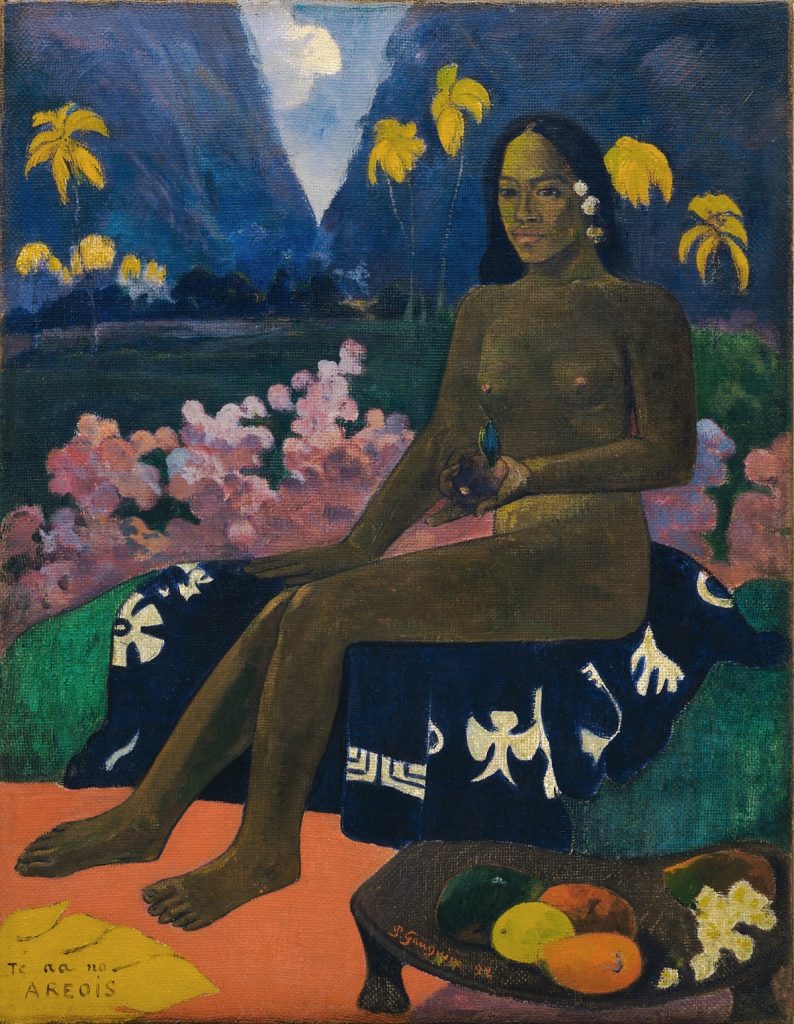

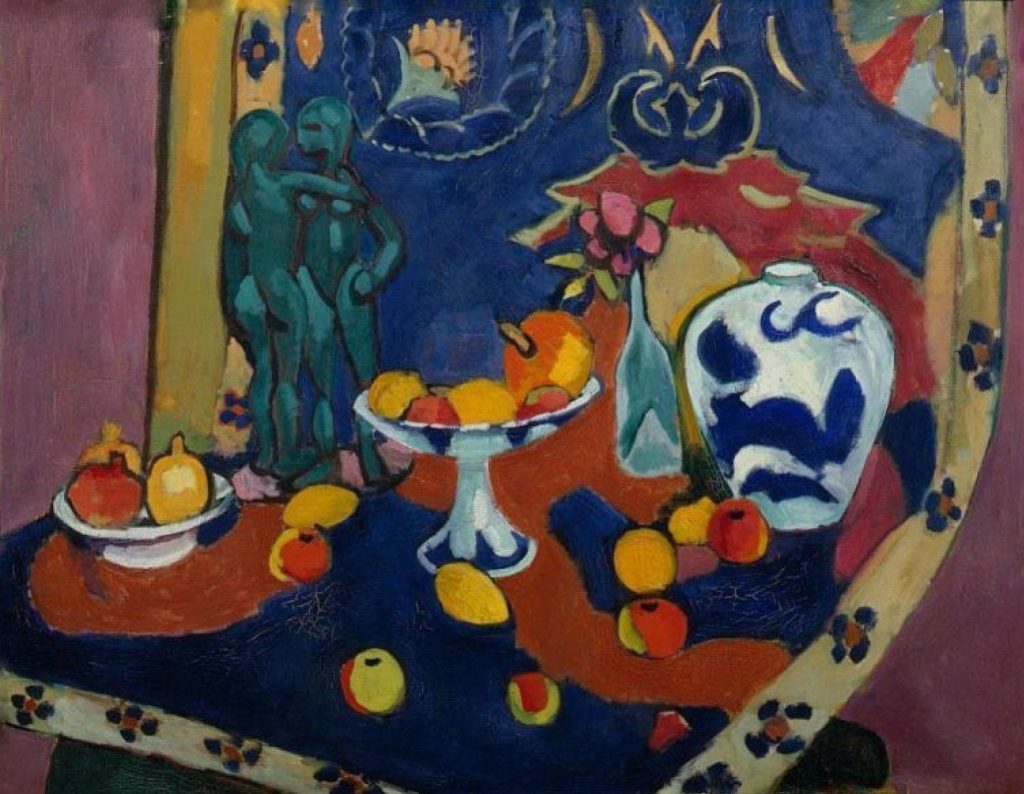

With ‘La Desserte’, in particular, Matisse had already surpassed Gauguin by allowing a decorative floral pattern, drawn in sweeping curves, to spread across and integrate different plane surfaces- tablecloth, wall hanging- in echo of a tendency pioneered in the paintings of Gauguin’s Tahitian period, in particular,‘The Seed of the Areoi’ of 1892 inMOMA, New York; ‘The King’s Wife’ of 1892, in the Pushkin Museum; and ‘Woman Holding a Fruit’ of 1893, and ‘Month of Mary’ of 1899, both in the Hermitage Museum.

We do not know which paintings Matisse (or, for that matter, Picasso and Derain) saw in the memorial exhibitions at the Salon D’Automne and the De Montfried Collection in the years following Gauguin’s death in 1903; but it is clear that the ‘barbarous’ poetry of the work insinuated itself into the consciousness of a younger generation of aspirants, the former ‘wild beasts’, or ‘Fauves’. The more one considers it, the more it becomes clear that the influence of Gauguin gradually asserted itself in Matisse’s development from the late 1900’s onwards, even over his earlier obsession with Cezanne, and notwithstanding, either, his response to the seismic eruption of Picasso’s ‘Les Demoiselles…’ (which was also, in itself, a response to Gauguin’s primitivistic example).

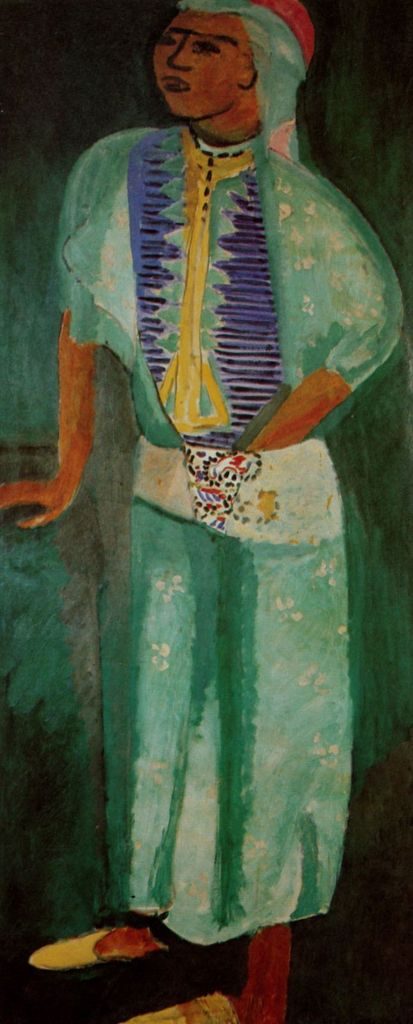

Immediately following the visit to Moscow, Matisse embarked on a trip to Morocco in January of 1912, (as had Delacroix, Gerôme, and many other French painters during the previouscentury), in order to experience a more exotic and elemental life, and to escape from the enervating listlessness of the urban miasma (a recurring impulse among those modernists of a romantic disposition.) The paintings Matisse made after this trip continue Gauguin’s enterprise of the monumentalising of native types and tribespeople, whom Matisse had also sought out, although he never strayed far from Tangier and his base there, the ‘Villa De France’, one of the best hotels in town.

One of the most remarkable episodes in his life was his decision, in 1929, to make the trip to Tahiti by way of New York and Los Angeles. The very fact that he did so in spite of what he must have known of the follies of distant travel, and of the inevitable disillusionment already prophesied by De Nerval and Baudelaire, testifies to the magnetic pull of Gauguin’s art, as does the all-or-nothing throw of the dice that desperation and insane courage had induced Matisse to try.

Not one to be seduced by the myth so assiduously fostered by Gauguin and his supporters, Matisse nonetheless felt it imperative to experience for himself what may have remained of this tropical paradise: ‘Having worked fifty years in European light (which is silver) and space, I always dreamed of other proportions which might be found in the other hemisphere. I was always conscious of another space in which the objects of my reverie evolved. I was seeking something other than real space …. I might add (moreover) that I did not find it in Oceania.’

Matisse’s recorded responses to Tahiti are contradictory. The light there was ‘golden’ (as opposed to that which he experienced in New York, where he found ‘a very pure, non-material light, a crystalline light- very beautiful, if you knew where to look’), the men and women incredibly beautiful, the sun overwhelming; but he could not and did not work there. Whilst Gauguin had been able to create prolifically there in both painting and sculpture, the environment and climate were energy-sapping for Matisse.

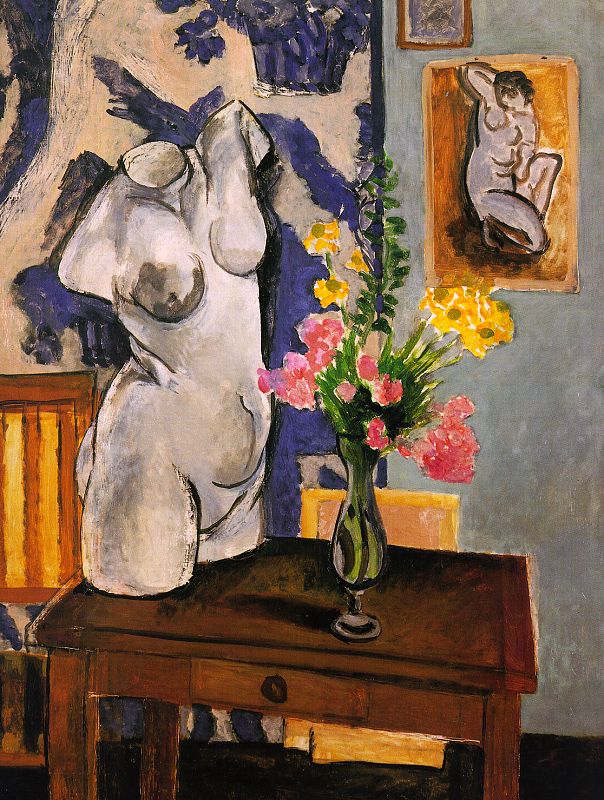

However, seen in a particular light, Matisse’s whole subsequent development can be interpreted as at once an apotheosis of Gauguin and a critique of him, albeit an affectionate one; indeed his whole art is both. How? In a phrase, through the emancipation of line. Matisse’s line is more eloquent in itself, freer from a tightly-bounded sculpturesque form, and hence ultimately more form-defining; see, for example, ‘Greek Torso and Bouquet of Flowers’ of 1919 (Sao Paulo). ‘The role of painting, I think, the role of all decorative painting, is to enlarge surfaces, to work so that one no longer feels the dimensions of the wall’. And to that end, the freeing of drawn line from its role as marker of the perimeter of modelled form (as it tends to be for Gauguin in all but his very last graphic works, such as the monotype ‘Heads of Two Marquesans’ of 1902, in the British Museum) was crucial.

Matisse and Picasso were far from transparent in acknowledging their debt to Gauguin (and Van Gogh). Matisse came close to denying it, citing Moreau and Redon instead, but Gauguin’s influence is everywhere. Picasso was influenced by Gauguin’s literary, sentimental side, and by his sculpture and pottery; Matisse’s was a much more radical appropriation, as shown by his broad patterning of landscape into interlocking or intertwining flat shapes, in ‘Pink Nude’ of 1909, ‘View of Collioure’ of 1905, and the combining of arabesque decorative backgrounds with simplified patterns of foliage and fabrics, the placing of flower studies together with a nude model in which contour drawing plays the decisive part, the orientalising of female features; most of all in following Gauguin’s example by transferring voluptuousness to the whole decorative conception, yet surpassing his achievement in that conception’s rhythmic completeness. Matisse learned from Gauguin’s mistakes as much as from his successes.

The radical simplification of drawn form, expanding to fill the whole picture space, as in Gauguin’s ‘Woman of the Mango’ of 1897 (Baltimore), and ‘The Moon and the Earth’ of 1893 (MOMA, New York) is echoed in Matisse’s ‘Young Sailor I’ of 1906 and ‘Young Sailor II’ of1906-07 (Metropolitan Museum, New York), though the pose in these last two paintings also owes much to one of Michelangelo’s decorative figures from the Sistine Chapel, and has strong suggestions of Van Gogh’s ‘Portrait of Joseph Roulin’ of 1888, in Boston, as well.

Just how much of a debt Matisse owed to both Gauguin and Van Gogh is evident in the comparison between his ‘Madame Matisse in Rouge Madras’ of 1907 (Barnes Foundation) and Van Gogh’s portrait of Augustine Roulin, ‘La Berceuse’ of 1889, (Boston); and between his ‘Seated Riffian’ (Barnes Foundation) and Van Gogh’s ‘Zouave’ of 1888 (Amsterdam). From Matisse’s Moroccan visits, ‘Fatmah the Mulatto’ of 1913 is Gauguinesque both in facial features and decorative costume; and ‘Fruit and Bronze’ of 1910 (Pushkin Museum), with its predominant blue/purple colouring, is one of his most Gauguinesque still lifes; all of which- bearing in mind also the unmistakable influence of Cezanne- demonstrates the comprehensiveness of the synthesis Matisse was making of diverse, even antagonistic strands of late 19th century French art.

I think Pierre Schneider is right to claim that Matisse’s Tahitian experience, after a period of gestation, re-surfaced in a flood of memories which in turn shaped much of the art of his later years, the paper cut-outs especially; the most Gauguinesque of these clearly being, I would suggest, ‘Sorrows of the King’ of 1952 (Pompidou Centre, Paris), in which the ‘sin’, the evil portents, are entirely sublimated into a ‘truly plastic space’ of breathtaking decorative splendour.

4 thoughts on “Alan Gouk: ‘Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, Part II: The Apotheosis of Decoration’”

Comments are closed.

Absolutely wonderful piece of writing. I particularly liked the way Alan noted where the paintings he is discussing are housed- ‘(Boston)’ etc. Is there another instalment coming up, as I’d love to hear him talk further about Matisse, in reference to his studious re-doing of Cezanne. Wonderful scholarship, and some of the best comments are in the notes, about the way the Brits haven’t got a clue, and are suspicious of Abstraction, a point I made on Abcrit.org in relation to Robin Greenwood. Thank You.

Patrick, you shouldn’t be ashamed of your countrymen. The way things look to me here in New York: you guys at Instantloveland and Abcrit and Brancaster are doing a good job of keeping civilization alive: you’re still aware there is such a thing as civilization—that it’s worth keeping alive, etc.

You’re right about Alan’s essay though: it’s great. My favorite footnote is number 2: the Mallarme poem: it’s translated by Wallace Fowlie. I studied French Lit. with Fowlie about 50 years ago when I was in college. Studied Baudelaire and Rimbaud and Mallarme. I was a cool guy—even though I hardly understood a thing back then. I understand a little more now—in no small part thanks to Alan. That’s what civilization is: going over the same stuff again and again: understanding things a little better, a little differently, each time.

Two wonderful essays, thank you Alan.

Once again, wonderful to read, clear, insightful and interconnected ideas from someone who understands what painting is about. I agree with Jock Ireland and believe Alan is someone who shows us how to look again at what we have looked at before. A rare gift.