James Faure Walker: ‘Dubuffet, Drawing and Disorder’

In his second piece for Instantloveland as a Writer-in-Residence, James Faure Walker wonders if the great advocate of ‘Art Brut’ and the authors of ‘How-to-draw’ manuals have anything to teach each other…

One

‘The lesser the drawing skill, the greater the creative contribution.’ Jean Dubuffet 1‘Batons Rompus’, Les Editions de Minuit, Paris, 1986, p. 23., quoted by Alfred Pacquement, ‘Scenes Champetres, Crayonnages, Recits, Conjectures’ in the 1991 exhibition catalogue, Jean Dubuffet, Les Dernieres Annees, Editions du Jeu de Paume.

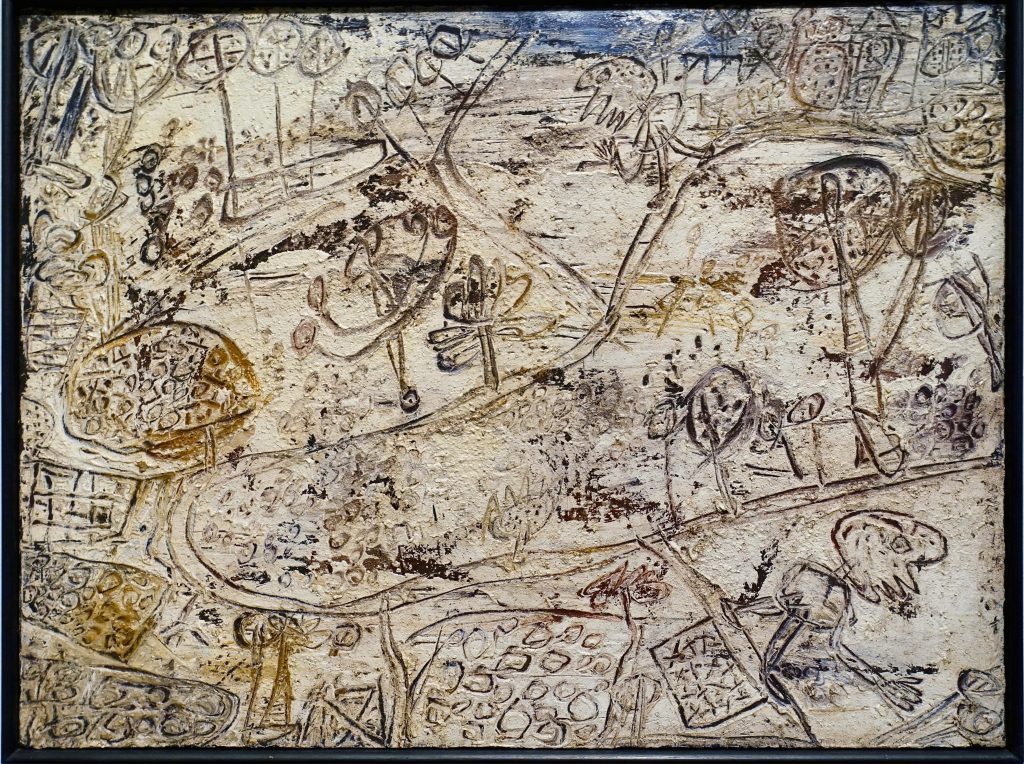

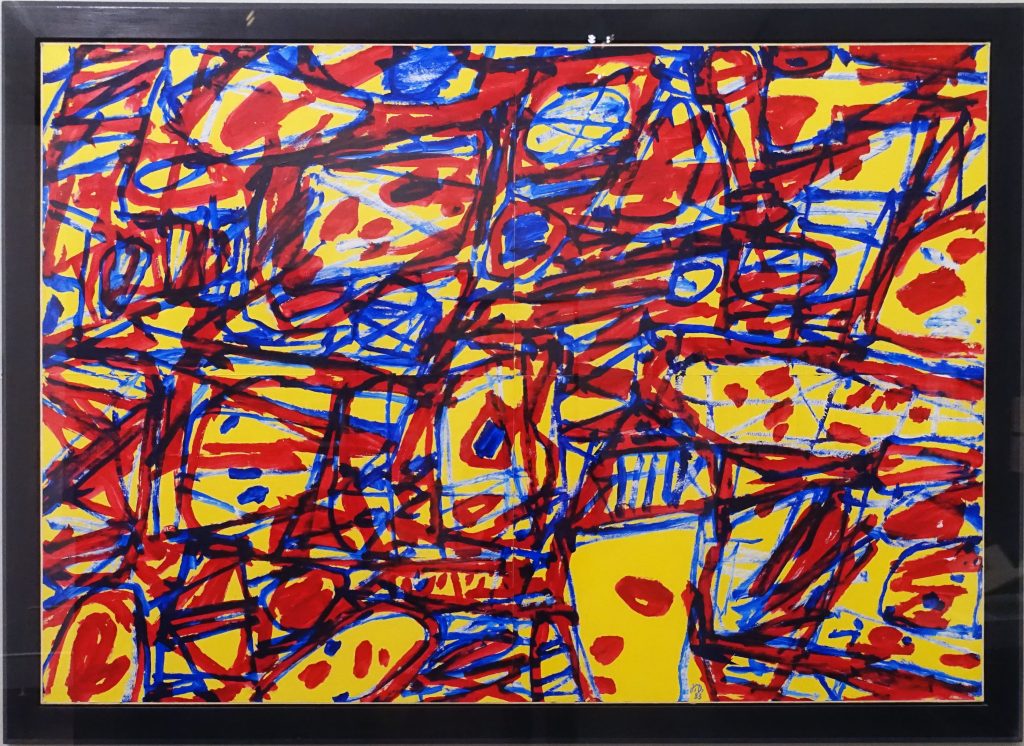

Sometimes I see an exhibition, and it leaves an after-image. In January I spent a couple of hours at the Dubuffet show in Valencia: it was a confrontation, eyeball to eyeball, with the blank staring faces, scrawled across in crazy patterns; the line that never rests.2At IVAM (Institut Valencià d’Art Modern) from October 8, 2019 to February 16, 2020. The exhibition had travelled from Marseille’s MUCEM (Museum of the Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean), and would end up in Geneva at the MEG (Museum of Ethnography), but this has now been postponed. If there weren’t personages as such, there were the ‘Hourloupes’, felt-tip doodles made large. Works by other artists in the museum dropped away. They looked self-conscious, cautious, posed, out to please. Dubuffet’s graffiti had the urgent look of the primal, uncensored, defiant and free of aesthetic principle. You could not come away untouched. It was a polemic against the pseudo-sophisticated.

The exhibition included a substantial showing of Art Brut, drawn from collections Dubuffet started in the 1940’s. For him these works represented, according to the organisers, ‘delusion-inspired inventiveness’. Here you could find a portrait of Queen Victoria constructed from seashells.

The exhibition’s subtitle was ‘A Barbarian in Europe’. Dubuffet likened western culture to a sewer. Our brains need to be ‘demagnetized’. The art of the west, over-refined and clever, was the aberration. The art we class as ‘primitive’ was where you would find the real creative energy: ‘there is no hierarchy in art, there is only invention.’ 3Part of Dubuffet’s own Art Brut collection can be found in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, which shows how difficult it is to classify.

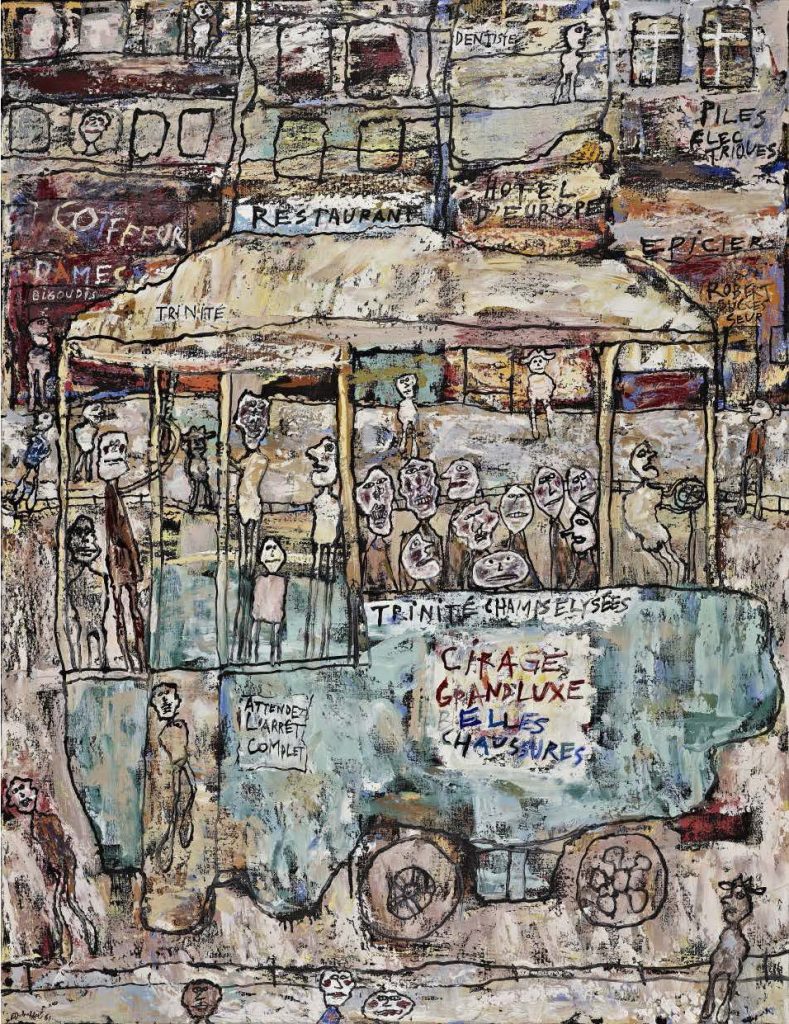

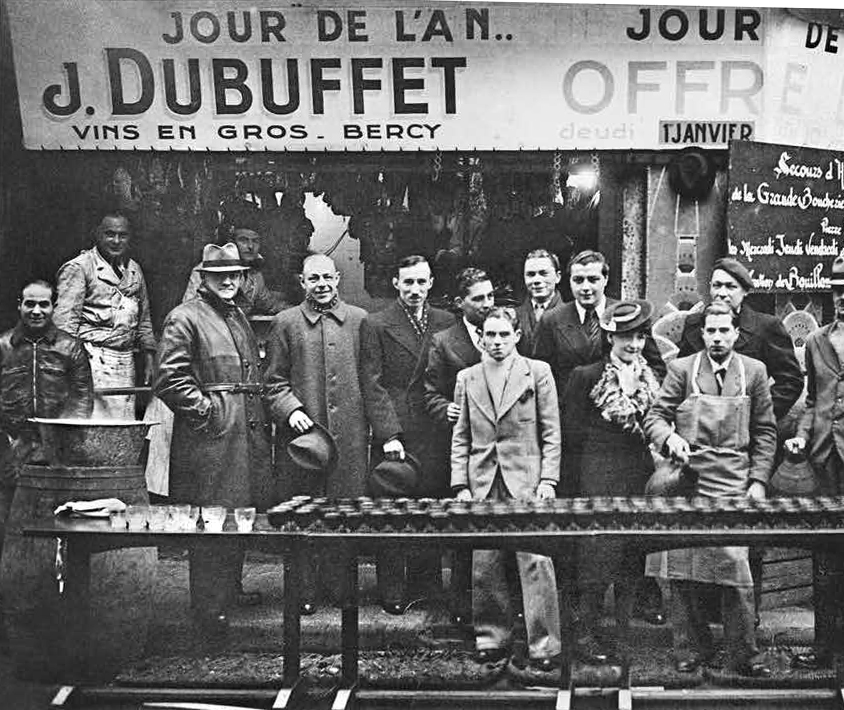

Dubuffet was notoriously combative and contrary in conversation, and some of his paradoxes were playful provocations: ‘Only nihilism is constructive.’ At the same time he appeared to be fully grounded as an ordinary citizen. There were clips from documentary films made in the early 1960’s, showing Dubuffet on the metro, or walking past the warehouses of ‘Dubuffet’, the wine business he ran in the early forties. With his business suit and trilby, he didn’t look at all like an artist. He taunted the arty elite with the mindset of a no-nonsense Paris commuter. Readymades?

‘…An intellectual can receive immense success for having presented a certain object to the enchanted cultural body – a urinal, a bottle rack – that all plumbers and cellarmen have been admiring for fifty years. But it never occurs to anyone that the plumber and cellarmen played the role of discoverers.’ 4Jean Dubuffet, 1968, ‘Asphyxiating Culture and Demagnetization of Brains’, (translation by Carol Volk, 1988. published by Four Walls Eight Windows, New York. Page references taken from Verdrusz Book, Glasgow edition, 2018). Where not otherwise cited Dubuffet’s quotations are from this source. Page 41.

How much of this was tongue-in-cheek? Duchamp had helped Dubuffet in the USA with translation, and probably would have enjoyed this dig. Dubuffet was sparring with the phoney group-think of ‘art appreciation’: we should cultivate the raw rather than the cooked. He had been close to Miro and Masson in the 1930s. Surrealist subversion ran through everything he did, right up to his death in 1985. Somehow, he made it all work, managing to be both authoritative and ambiguous – automatism with sure-footed composition. There was no judging, no correcting, no changes of mind. Just a flow of crazy ideas and imagery. He treated the surface as if it were earth, scraped, harried, and ploughed, a farmer nurturing the crop. He spoke of the fermenting soil as if it were the collective unconscious. He used a black ground colour to achieve the fluorescence of a blue. This was no unskilled amateur.

Two

Over the years I have amassed a collection of ‘How-to-draw’ books, from roughly 1880 to 1970, without having any reason for doing so, apart from finding them selling for nothing in junk shops or discarded from art school libraries – also, because they are generally frowned upon. They can be irritating or amusing – depending on your point of view – with many stern words against mere scribbling. They also tell a different story from conventional art history. Many are wonderfully illustrated: it was the golden age of commercial art. Before the ubiquity of photos, advertising agencies employed artists. The details are fascinating: the props for a 1920 still-life, the grandads posing in armchairs with their pipes, ‘speed’ represented as biplanes and steam engines; diagrams showing how to hold the pencil. You could dismiss it all as ephemera, the advice as obsolete as the technology depicted. If you were an actual teacher, you would say you can only learn so much from a book, from copying the pictures. The RA Schools actually banned these publications. Students often ignored the suggestion that they should draw whatever was around them; instead they copied the drawings with tracing paper.5 For an extended discussion see my ‘Learning to Draw from Forgotten Manuals’, 2013 conference paper published, ‘Drawing in the University Today’, 2018, PSIAX, nº3, series II, Universities of Porto and Minho. https://www.jamesfaurewalker.com/learning-to-draw-from-long-forgotten-manuals-james-faure-walker-2013.html But we all start from somewhere, and if you had no access to an art school, or knew nothing of museums, this is where you might have begun; and the formulae for drawing horses, trawlers or cars (vintage) can still come in handy.

My book collection is mainly British. For the first half of the twentieth century the writers provide sweeping introductions, nods to the old masters, step-by-step exercises, and a few concessions to modern life – draw a telephone if you have one. There is the occasional diatribe against wrong-headed teaching. Some acknowledge the new free thinking, but others weigh in against ‘ugly modern’ art as the work of the insane, the Bolsheviks, or both.

Bearing in mind Dubuffet’s tirades against cultivated taste, his dismissal of the very idea of drawing as a ‘skill’, what place, if any, would the drawing manual have in his Art Brut universe? Dubuffet compares western decadence with rotting fruit. He knew his vineyards. He looked for the primal source, down through the soil to the roots. He asked how the untutored and the raw could flourish, unaffected by what passed as ‘culture’. Were the readers of these instruction books potential recruits? Would they be contaminated by the advice of the experts? Perhaps we shouldn’t take his argument too literally, just let the play of imagery wash over us. But the question remains of the untaught versus the taught: whether you can unlearn all those reflexes you pick up in life drawing classes. If you were to take the ‘ordinary’ person‘s point of view, you could become the philistine who only looks at the Western canon that Dubuffet affected to despise; you dismiss anything unfamiliar and ‘experimental’. The vital juices of creativity mean nothing at all. You are comfortable with drawing that shows skill, with impressionism, with anything traditional as long as there is an explanatory label. You see children’s art as full of ‘mistakes’, laugh at naïveté, and just see other cultures as primitive. So there was the contradiction that faced the idealistic avant-garde of the 1930’s. The man in the street wasn’t ready for the medicine.

Commentators in the press periodically complain of the decline of drawing; they claim that art students are ‘no longer’ taught how to draw. In fact every other drawing book going back to the 1880’s and earlier makes that same claim – as if it were one of the lost accomplishments of ancient Greece. In recent times Art departments in universities have been singled out, as if all they taught was conceptual art. I recall many conversations with non-art people who repeat this news to me (I don’t let on that I might be an artist myself); they mention the ‘School of London’ as the ‘real’ artists, who have heroically resisted the Modern. What strikes me about these conversations is the absolute certainty that: a) observational drawing is a basis for everything; b) it can be successfully inculcated by teaching; and c) everything else that has been achieved over the past hundred years goes out the window. For the record – just look at the ‘Large Glass’ – Duchamp was a skilled technical draughtsman.6 I owe this observation to Irving Sandler, who used to speak of Duchamp as an incongruous figure in New York in the fifties and sixties, like a dandy. See: www.meltonpriorinstitut.org/pages/textarchive.php5?view=text&ID=159&language=English I have nothing at all against drawing – most days I draw something from observation – but I do object to the narrow-mindedness, to shrinking art education down to ‘training’ in one or two approved ‘skills’. In the past twenty years, private art schools have sprung up, sensing a gap in the market, promising the proper grounding. There is a half-truth here; studio teaching in university art departments is been rationed, the proportion of ‘theoretical’ study has increased, and the staff have to tot up research points for the funding league tables. There is little comfort here for progressive souls. Dubuffet’s onslaughts – always full of humour – do strike home, decades after they were poured out in his vivid imaginings.

So, I doubt whether this forgotten ‘How-to-draw’ library could release the raw art energy that Dubuffet extolled. Quite the reverse. The authors would dismiss his ‘scribbles’ as undisciplined rubbish. Amateur art societies might be more ambivalent. Plenty of retired people enrol in art classes, enjoy ‘mindful’ life drawing, or a pleasant still-life. It is recreational. Some might go along with Dubuffet’s ‘constructive nihilism’, but many just want the quiet life. If their painting is a little naïve and wobbly, no matter; it is honest and tasteful. For Dubuffet, though, it wouldn’t be sufficiently unhinged.

Three

‘I am an individualist, that is to say that I consider it my role as an individual to oppose all constraints brought about by the interest of the social good. ….It is for the State to look out for the social good, and for me to look out for the good of the individual. The State has but one face for me: that of the police.’ 7Jean Dubuffet, ibid. p. 7.

When I first read Dubuffet’s ‘Asphyxiating

Culture’ I imagined curators at the Tate, the Arts Council, the Royal

Academy, dressed in uniforms according to rank, with rules and regulations

pinned up in the galleries, penalties for wrong thinking. The book was first

published in 1968, a time of liberation politics and the Paris student

uprisings, and ‘Western Art’ was an

easy target. Half a century later, the Tate does indeed have uniformed guards,

and wall texts; but the ‘uniform’ consists

of a simple black t-shirt, the wall text gives helpful suggestions for

what you might like to think about, and those ‘guards’ might well be protecting the odd Dubuffet alongside all

the other art. Today museums tread carefully, wary of causing offence,

tiptoeing around ethnology; in retreat from treating art as art, with labels

stressing context. This makes us feel enlightened and socially responsible

citizens. I recall time spent in the Museum of Mankind when it was behind the

RA, just looking at the exhibits as art works in their own right. I have

Herbert Read’s ‘Education Through Art’

of 1943 in my collection, full of analyses of children’s drawing, campaigning

for a deeper understanding. Today we look at exhibited art less as a learning

resource than as a tourist attraction. We traipse around museums designed by

star architects and respond to celebrity artists. A visitor trooping through

the Antony Gormley RA installation was heard to say how much better it was than

the ‘awful’ Abstract Expressionist

exhibition there.

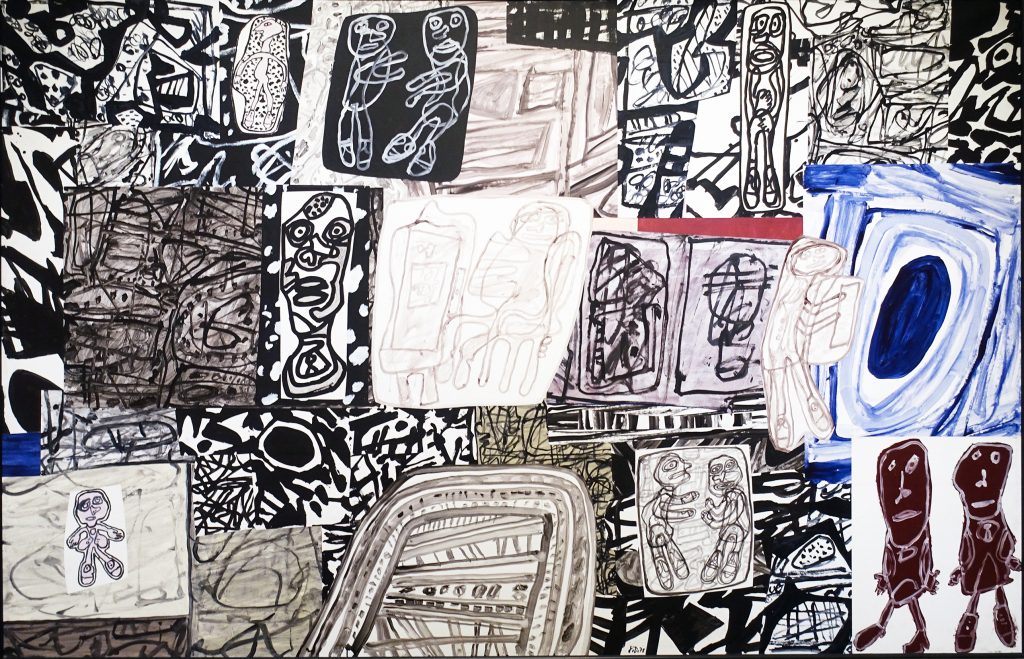

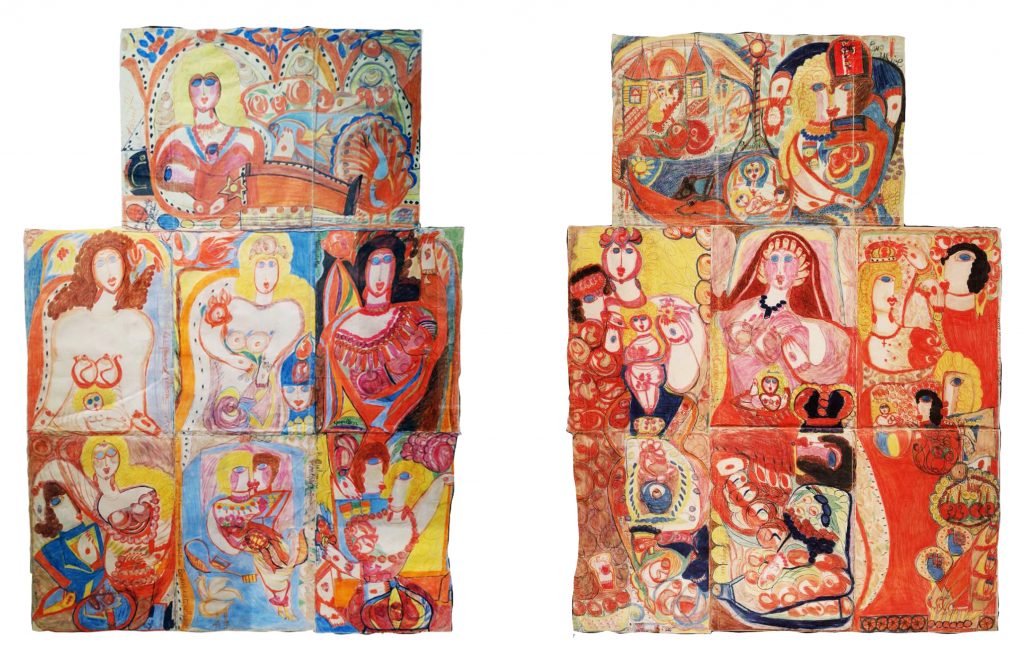

My favourite Dubuffets are the late ‘Theatre of Memory’ works, collages of dozens of drawings. I had seen these in exhibitions in Paris and knew what to expect. They have so much of the city about them, crowds of commuters rushed for time. There were cars and parks, but nothing as restful as an open landscape. The Valencia show opened with ‘Dramatisation’ of 1978, and ‘Les Pas Perdus (The Last Steps)’ of 1975, which was a film about a rich married woman falling for a young worker. They recalled the great late paintings of Leger, the parades, workers and picnics, but without the dreamy idealism.

‘Seurat’s picture ‘La Grande Jatte’ in the Art Institute of Chicago would, in my opinion, be infinitely more beautiful – would have more style and would, without doubt, stand as the greatest work of French Art, had it been painted in the technique of the local tone.

Seurat’s lack of force is due to the fact that he submitted to the impressionist diffuseness of his time and employed it in a composition where the breadth demanded the use of local tone. Rousseau, Le Douanier, who also worked in the middle of the Impressionist period, knew how to hold out against this diffusiveness. He employed the local tone. And that is what gives him his quality and style.’8 Fernand Leger, 1937, ‘Apropos of Colour’, translated by James Johnson Sweeney, Transition, New York, page 81.

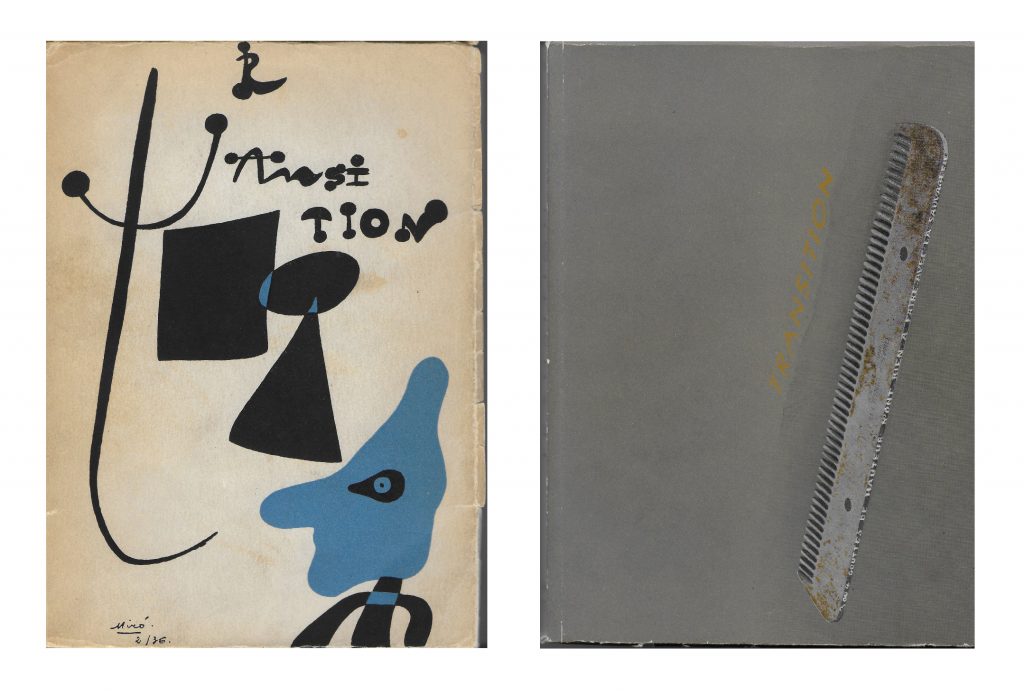

This is not Dubuffet discussing local colour. It is Leger, writing in 1937. Dubuffet was close to Leger. This was written in ‘Transition’, a journal with contributions from everyone from Mondrian and Aaron Copland to James Joyce.9 I have two copies of the journal, Transition, nos. 25 (cover by Miro)and 26 (cover by Duchamp), from 1936 and 1937. They give a hint of the pre-war milieu Dubuffet would have known during the formative period when he had twice given up on his painting career to run his wine business. Contributors included: Miro, Dylan Thomas, Franz Kafka, Louis Aragon, Fernand Leger, Le Corbusier, Paul Strand, Marcel Duchamp, Hans Arp, James Agee, Paul Eluard, Randall Jarrell, Raymond Queneau, James Joyce, Aaron Copland, Man Ray, Andre Lhote, Ladislaus Moholy-Nagy, Piet Mondrian, Erwin Panofsky, Alexander Calder, Josef Albers, John Piper. The issues include a section called ‘Inter-Racial’. When we started the magazine, Artscribe, in 1976, this was what I had in mind. Leger’s words are a reminder that the idea of rejecting and remaking the recent past was in the air. Dubuffet’s painting ambitions had been frustrated before the war. He made puppets, learned the accordion, so as to perform alongside his wife, Lili. He then ran a successful wine business in occupied Paris. When he reinvented himself as an urban primitive, and more or less established the concept of ‘Art Brut’ in his forties, he had already seen more than enough of life’s bitter side. The etiquette of drawing was far from his mind.

Four

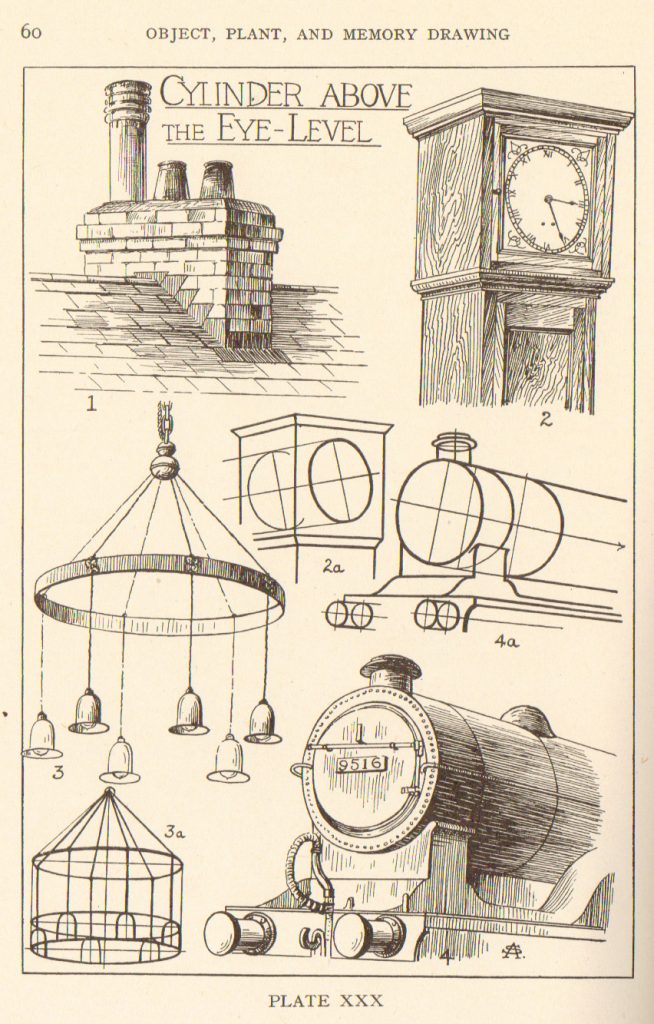

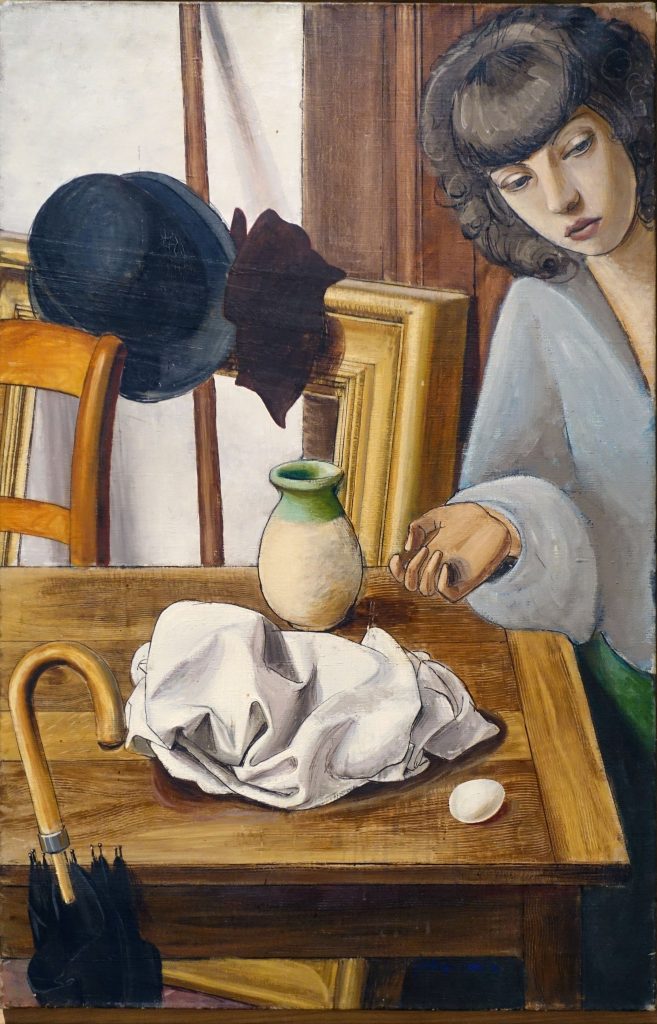

The examples of good drawing in the ‘How-to-draw’ books show a clean-living, well-ordered world. You enter the home of the competently sane.10 For example: ”the cave dweller returning from his hunting would spend the dark hours painting and drawing on the rough walls of his home, helped perhaps by the flickering light from a fire…..We know, too, that there are among us today some who return home from very different work in the city, factory or field, and find the very same satisfaction and a great deal of healthy ‘release’ in leisure hours spent with pencil and brush.” Ronald Smith ATD (1942), Teach Yourself to Draw’, The English Universities Press, London. Page vii. You can find bizarre juxtapositions of everyday objects – in the 1900’s you could even buy a hamper of appropriate still-life objects – but the point was to measure, to translate what you see and get it right. Circles seen from an angle could mean trouble.

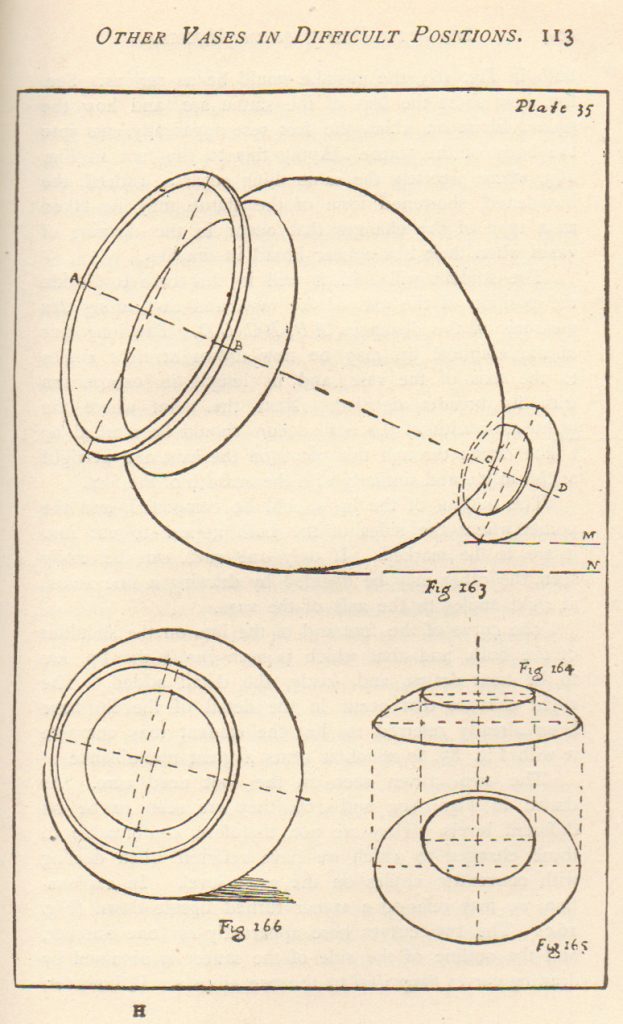

I was looking through a collection of pre-war architectural watercolours by the artist, Maurice Andre Kaspar, for a forthcoming exhibition.11The Life and Works of Maurice Andre Kaspar, 1892-1946, Bankside Gallery, London, January 256 to 31, 2021. Though established in Switzerland, he was not widely known. He was self-taught. What makes the paintings interesting is that he was an architect whose job it was to inspect the physical and sanitary conditions of old Geneva buildings. There was one study of a waterwheel, and at first it looked a curiously-shaped mechanism. And then, as I became more familiar with his approach, I realised this shape was an unintended distortion – easy to make, and, you might say, uncensored. That wheel could never turn. I thought straightaway of a formidable exercise in the chapter, ‘Other vases in difficult positions’, in ‘How to Draw from Models and Common Objects’ of 1919, explaining how to represent circular forms seen at an angle looking upwards.12W.E. Sparkes, (1919) How to Draw from Models and Common Objects. A Practical Manual. Cassell and Co, London. Once I saw that waterwheel as deformed I could not unsee it, nor could I switch over to seeing it as creatively unskilled. A week later I came across a plaque in a church near Dedham where Constable’s brother, Abraham, a miller in the family business, said of one of the early watercolours: ‘John’s mill wheels look as if they would really go round.’ This could be a trivial test to apply – it probably is – but ellipses are notoriously difficult, especially in peripheral vision, or in close-up, as Cezanne discovered when painting his still-lives. Dubuffet’s distorted forms look integrated because they are squashed flat – and his distortions became part of the stylization. I came across another example, from a 15th-century altarpiece in Valencia, and if ‘How to Draw from Models and Common Objects’ had been available to the artist, perhaps St Catherine’s wheel – no comfort to her – could have formed a proper circle.

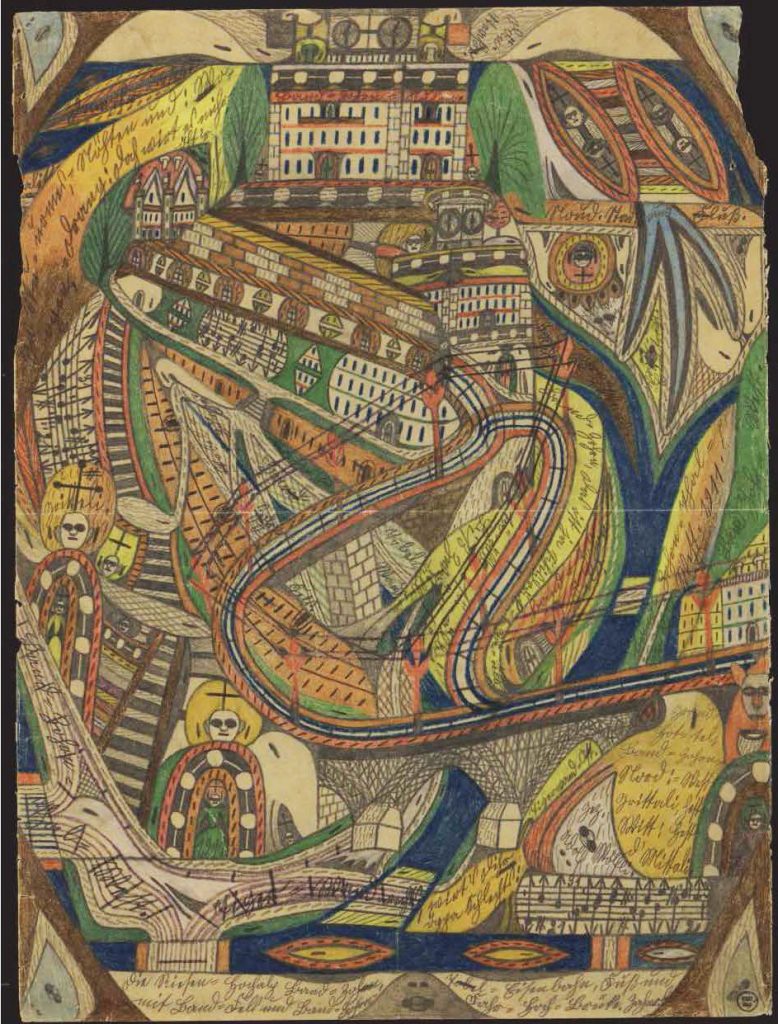

When we dream, we are passive observers under a spell; there are no art tutors steppinginto correct perspective. We find we can fly. It is the free-floating world of fantasy of religious art, folk art, even children’s art. Do we need to distinguish between the truly ‘visionary’ and the knowing imitation? Is the imagery meant for private solace, or for general consumption? One of the most mesmerising pictures in the ‘Art Brut’ section of this exhibition, by Aloise Corbaz, has the tenderness of a devotional painting, with the visual logic as peculiar as the title – ‘Miraculous fishing of Thalie’s ankle boot’. Adolf Wolfli’s ‘Untitled (the great railway of the ravine of anger)’ of 1911 is instantly recognizable as a Wolfli, pulling you along its winding story-line, a melting Piranesi. Dubuffet touches on this dilemma:

‘…the artist finds himself drawn toward two contradictory aspirations, to turn his back on the public or to face the public. Thus, we see the great Adolf Wolfli write on the back of his painting the price he assigns to them, which is sometimes a million billion, sometimes a pack of tobacco.’ 13Jean Dubuffet, ibid. p.44.

Five

Dubuffet writes of the 1900’s as a period when innovation meant wholesale rejection of past conventions. It isn’t always apparent what art of that period he did or didn’t favour. Perhaps he needed to duck out of the shadow of Picasso. By the 1960’s he was more settled, and had his own working rhythms, his own formulae. Could he have produced a ‘How-to’ manual, everything boiled down to one technique? Not easily. Every few years he re-invented himself.

If I could time-travel back to the epoch of these drawing manuals, especially those so wrapped up in the received wisdom of academic realism, I would throw back some questions the Dubuffet exhibition posed. Did they think drawing was just about being accurate? And if not, what else was involved? Where does art really come from? Do they feel the unconscious, dreaming, the accidental, the works of cultures remote from our own, have anything to offer? Couldn’t they recognize that a method as simple as collage made painting turn a corner? Perhaps I am being unreasonable, because there are good reasons for wanting the security of a sound drawing technique, however that is defined.

The manuals of the 1920s and 1930s do acknowledge the revolutions of modern art, but tend to return to the complacency of a middle-of-the-road academicism. But sometimes you come across a first-hand encounter that makes you think twice:

‘All the “Isms” of the last fifteen or twenty years merely represent the effort to retain or get back to the freshness and force of first impressions and they have been, nearly all, futile because of a self-consciousness which is too often but the sign of incompetence.’

‘Nearly thirty years ago the Anarchists of Art in Paris suggested that the only way to get forward again was to burn the museums and make a fresh start. But the museums are still with us, better organized and more useful than ever.’

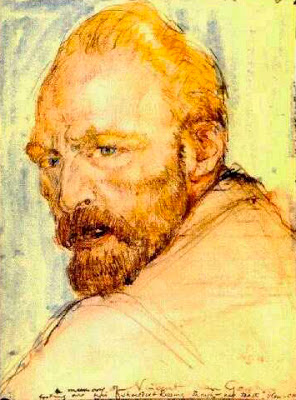

‘I happen to have known personally at

that time two of the men who, since then, have been exalted to the position of

leaders of new movements in Art – Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin…both of

them came to the study of Art professionally after they had already arrived at

mature years, with a considerable experience of the world and life behind them

(…)

Being men of character and ability they thereupon sought a means of expression through the ruder and more primitive forms of technique. The result of this activity had been mainly to re-assert the importance of design and clearness of colour: nothing very surprising after all. Van Gogh as I knew him certainly would have been the last to claim that he was doing anything absolutely new. The names of Rembrandt and J.F. Millet were constantly on his lips. Gauguin was more ‘intransigent’. As an extreme individualist he disliked the teaching of academies with a violence that grew to be almost a mania.’ 14A.S. Hartrick (1921), Drawing, From Drawing as an Educational Force to Drawing as an Expression of the Emotions, Pitman, London. Pp. 8,9. Further details on Hartrick can be found at: http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~hartrickclan/genealogy/article4.html

The passages above are from Hartrick’s ‘Drawing: from Drawing as an educational force to drawing as an expression of emotions’ of 1921. Two of Hartrick’s students suffered serious mental distress. One was David Jones , the other was Thomas Hennell, who replaced Eric Ravilious as a war artist in Iceland in 1943, but was himself killed in 1945. 15A new biography of Hennell by Jessica Kilburn will be published this year. See: http://www.pimpernelpress.com/thomas-hennell He suffered from schizophrenia. Would you guess this from looking at his work? There are traces of Van Gogh in the drawing, but the watercolours I have seen suggest that observing and recording what he saw, concentrating just on what was there in front of him, was what mattered. As in many cases, there may be disturbance in an artist’s mind, but what is painted can be serenely objective. Since Dubuffet began assembling his collection in 1945, psychiatry has moved on. The pictures he collected tend to be strangely rigid, fixated on architecture, with obsessive systems, babbling stories. The connection between the inner and outer worlds is never straightforward.

Did the Valencia exhibition’s after-image last? Yes and no. The organizers recognized Dubuffet’s contradictions, but saw them as propelling his investigations. He touched on questions that get less attention today than they might. Perhaps we find ‘Art Brut’ an unconvincing concept. We compartmentalise the art of the professional, the amateur, the outsider, the child. I can’t recall many recent conversations about painting and the unconscious. ‘Art Brut’, with all its cross-cultural connections, has an underlying humanism. It has a particular relevance, given the rise of division and nationalism in Europe, and patterns of mass migration – including, of course, the current spread of coronavirus. He would have ridiculed the feel-good mission statements of art schools, the fake intellectual jargon, the academics rebranding dull art as ‘research’. From a 1968 perspective our culture looks tame, conformist, and colluding with fashion and the market. Yet, if you took his programme literally, with its call for the disruption and subversion of institutions, it has echoes of the ‘alt-right’, of Trump’s rampant individualism.

Dubuffet left a legacy, especially in the USA after his stays there from 1950 onwards: think of de Kooning’s ‘Women’, or of Oldenburg, who was in the audience of his 1951 Chicago lecture; and not forgetting Schnabel and Haring.16For an extended discussion of Dubuffet’s influence in the USA see Pepe Karmel, 2002, ‘Jean Dubuffet: The Would-Be Barbarian’, Apollo (London), vol. CLVI, no 489 (new series), 2002, available at: https://www.academia.edu/9990609/Jean_Dubuffet_The_Would-Be_Barbarian What he produced predates subsequent outbreaks of funky figuration by decades.

I am not sure what I think about drawing skill: does it just mean ‘look what I can do’? In abstract painting the authenticity of a drawn line is a tricky question. To look secure, it mustn’t look forced, impatient, vague, or be there just to help out an otherwise floppy composition. I am rarely convinced by gestures driven by angst, real or simulated. I prefer detachment. Perhaps that is temperament. I like to feel the artist got over his or her upsets before picking up the brush. It is also hard to make drawing look casual. Without the pull of a suggested image, or structure, it can be no more than ‘mark-making’ for its own sake, or just an exercise in arabesque, doing nothing much. Dubuffet was not a colourist, and needed his animated line to lasso the wildlife. It wanders across the surface, not so much obsessed as carefully watched and – to use his term – policed. What did he really mean by ‘creative’? Certainly not the ‘well-painted’ picture, nor pictorial carpentry, nor indulgent self-revelation, or random outbursts. He had fastidious taste – again I think of the wine trade. His methods for pictorial cultivation were truly ingenious. He threw in something that at first looks at odds with highbrow culture, but then you get its measure, its tensions and contradictions, even its restraint, and it becomes unforgettable.

3 thoughts on “James Faure Walker: ‘Dubuffet, Drawing and Disorder’”

Comments are closed.

Excellent article!

That you allow no final conclusion about Dubuffet is the way it should be. I’ve always found him a fscinating but unsettling artist. Despite his obvious attraction as a model, it is dangerous to see his work as style only. Also I’ve always been critical of outsider art, as all art takes place within cultural boundaries and has even less meaning now that Dubuffets lessons, and the lessons of the surrealists, have been so widely spread. You also raise some interesting questions about drawing. William James wrote (& I think I’ve got this right) ‘The world comes at us as if fired from the barrel of a revolver’. By which he means, I think, that our sensation of reality is overwhelming and instantaneous. Drawing needs some sense of this, whether Michaelangelo or amateur, and that is not something that can necessarily be taught. The thoughts you’ve raised are many so I’ll just say thanks for the article.

A thoroughly absorbing read. In particular I’m intrigued by the contrasts made between the “books of instruction” and drawing as a product of thought and belonging, not just observation/depiction.