John Bunker: ‘That was Now, This is Then’

While looking through a series of catalogue essays outlining aspects of abstraction in the last decade of the last century and the early years of this one, I came across a real gem: a short, sweet polemic by Peter Schjeldahl, written in 1998 for the catalogue that accompanied ‘Abstract Painting Once Removed’, an exhibition of international artists in Houston, Texas. In this essay, Schjeldahl describes, as he saw it, the state of abstraction as the new millennium approached. He simplifies radically, but adroitly: his précis of the significant changes that abstraction underwent since its inception is both beguiling and easy to love; the lack of jargon, and the breadth and depth of insight condensed into easily digested, quick-fire sentences are highly refreshing. What makes this mini-manifesto stand out, however, is the innovative decision to divide the history of abstract painting into ‘Abstraction l’ and ‘Abstraction ll’:

‘Abstraction l began with Wassily Kandinsky, et al., a decade into our departing century. It was about purifications: pure essence or pure objectivity, mystical intuition or utopian enthusiasm, rationalisation of form or mirror of the soul, hierarchy or anarchy- no matter, so long as the favoured intoxicant came straight from some ineffable bottle. Abstraction l hurried to get to the bottom or the end of things, and its alacrity caused refreshing breezes. Then, in the 1960s, Abstraction l attained the only form of purification that was ever truly available to it: more or less complete sterility.’

Schjeldahl contrasts this judgement on ‘Abstraction l’ with what he sees as its young, lively and biologically diverse successor: ‘Abstraction ll uses the microbe-free culmination of Abstraction l as a petri dish in which things can grow: selected things, choice contaminants. Abstraction ll kicks in after a spell- in the 1970s and 1980s- when dominant sorts of painting more or less threw the exhausted, hypersensitive medium of the modern picture open to the dirty air.’

Reading Schjeldahl’s piece allows us to go ‘back to the future’, as it were, in the sense of weighing up his provocative claims about abstraction’s past, and checking on his predictions concerning ‘things to come’ from our vantage point, here, in the present tense; which brings us neatly on to Dan Coomb’s latest curatorial excursion, ‘Stairway to Heaven: Abstraction Now’, which unfolds through the well-appointed corridors and meeting rooms of London law firm Watson Farley & Williams. Since the show dips in and out of walkways and private spaces, it’s not possible to get an overall sense of the exhibition, but it hangs easily and fluently between hallways and meeting rooms; and there’s a certain dark and yet not unpleasant irony in the ‘stairway’ to paradise and eternal peace making its way through the circuitous hallways and meeting rooms of corporate law. So, how might the work in this broad survey of contemporary British abstraction measure up to a Schjeldahlian reading?

‘Today the painting epoch of Abstraction ll gathers ideas and energies, building through trial and error toward a climax, I rashly predict, that will occur around the centenary of Abstraction I’.

In other words, somewhere around 2010. We are now close to 2020: does ‘Stairway to Heaven’ fulfil Schjeldahl’s prophecy, or does it simply continue to invoke Abstraction l by clinging to a discourse that predates the rise and fall of Postmodern critique and parody? As the hype around the recent Hilma af Klint show at the Guggenheim demonstrated, notions of ‘the heavenly’ are, for many, not that far down the signifying chain from ‘the sublime’. By having ‘Heaven’ in its title, is Coombs’ show reaching back past Led Zeppelin to the Abstract Expressionists? Or further back, past the great rupture of Modernity, to the loftiness of the Romantics, struggling to hoist their petticoats above the rising tide of cultural pollutants- the burgeoning working class; mass production; mass consumerism? And if it is, then why? When the second part of the show’s title is ‘Abstraction Now’?

It’s always a little disconcerting how ‘now’ turns so quickly into ‘then’; and in abstraction, how ‘then’ seems to be such a big part of ‘now’. At its inception, abstraction seemed to be so future focused; now, it’s easy to feel as though it has a morbid obsession with its own history. Many of its practitioners could be accused of using its past as some kind of vague spiritual valediction, or as a scaffolding on which to build a theoretical edifice around a rapidly imploding centre. Schjeldahl’s polemic excites, by its willingness to address potential futures for abstraction:

‘The mourning period is over. Away with delicately toned hysterias. History is not only not over, it has reawakened after fever dreams of history. Anyone who does anything now bets on the future. Abstraction is dead. So is the idea that abstraction is dead (…) at this early stage of Abstraction ll, comes the imperative to bring abstraction down to equality with other human brainstorms and capacities. No more self importance. No more fainting fits. In the 21st century, everyone must show up for work.’

The mourning period is over: but as it ran its course through the 1970s and 1980s, Schjeldahl asserts, certain artists- he cites the examples of Guston, Polke and Susan Rothenberg- responded to the sense of bereavement by violently siezing all that had been denied them by the overbearing repression of Abstraction I’s quest for purity; and (this) ‘virulence that raged immediately, because its agents had been most denied by Abstraction l, was figurational’. Schjeldahl goes even further: in truth, ‘the furtive secret of Abstraction l from its inception was that its vision quest was no more outside of figuration than Sri Lanka is outside of Asia. Abstraction l just posited special cases of the figurative, limiting its repertoire of forms to the mentally instrumental, like geometry, and the variously ambiguous, produced by arbitrary method, chance, or dreamy association.’

The link between these assertions and the work of ‘Stairway…’ artist Basil Beattie feels too obvious to ignore. Beattie moved away from the vagaries of his colour field paintings of the 1960s and 1970s into an emphasis on drawing that yielded a highly repetitive, personalized sign system; a harsh, seesaw realm in which severe figurative reduction clashed against almost gratuitous materiality. As with Guston’s ‘Klansmen’, de Kooning’s ‘Women’ and Pollock’s ‘black pours’, Beattie drags us into a world of archetypes and allegories: a claustrophobic hothouse of overtly symbolic man-made forms such as stairs, ladders, and in the case of ‘The Moment Before (Janus Series)’, the painting in this show, roads and low horizon lines, with their acute perspectives framed within the canvas in stacked vignettes that mimic the shape of a car’s rear-view mirror; all of this intensified by the vigorous application of the paint, and by its amplified sense of materiality, which emphasise the ‘act’– the theatre- of the painting process. What is his work, if not a Schjeldahlian ‘special case of the figurative’?

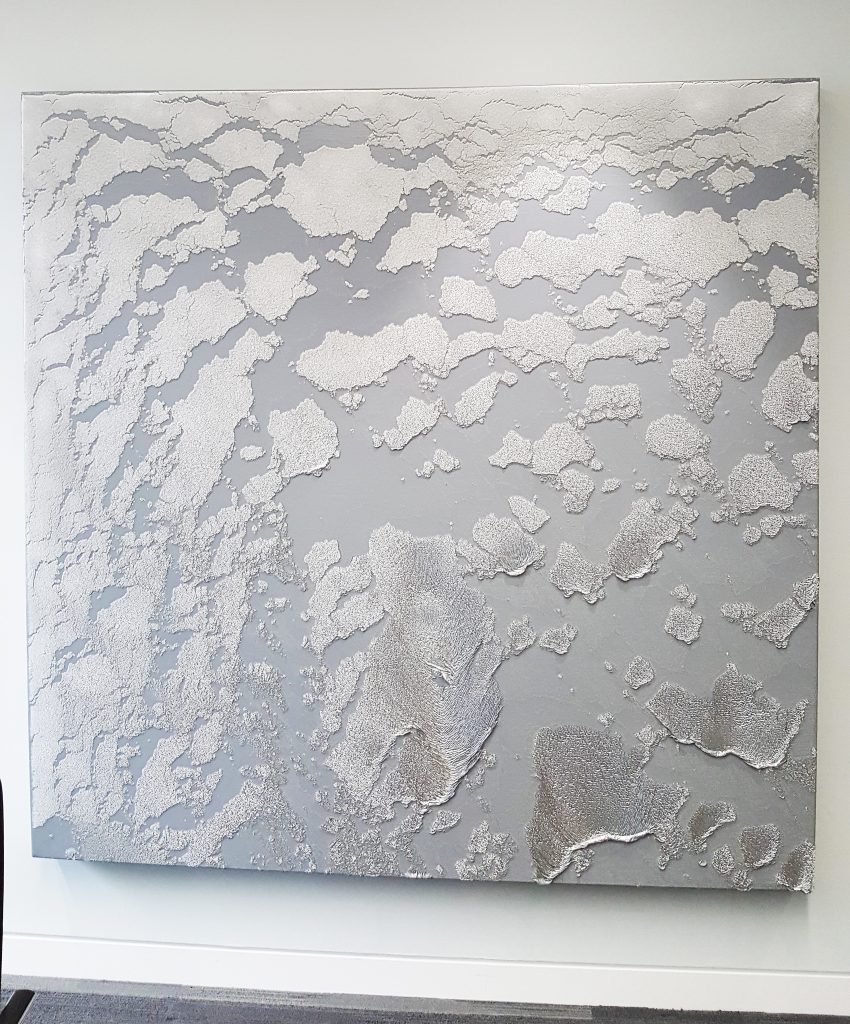

Alexis Harding, meanwhile, can be found at the intersection of Schjeldahl’s ‘arbitrary method’ and ‘chance’, theatricalizing Process Art through the clever layering of paints with differing drying speeds, upending the rational minimalist grid and allowing it to slip, split and warp as it slides down its support; the neoliberal slogan ‘managed decline’ comes to mind as Harding allows all things to bend to the irresistible will of time and gravity. In the cracking grey and silver surfaces of ‘Solaris‘, Harding’s ‘process painting’ embodies a form of entropic despair not unlike Beattie’s; both these artists seem to be involved in a particular kind of circularity and repetition, implicit in both Beattie’s subject matter and in Harding’s attitude to process. Does all this smack of a melodramatic ‘endgame’ painting? Are they somehow stuck on the cusp between Abstraction l and Abstraction ll?

Schjeldahl has a plausible answer. He ‘note(s) in passing an important transitional phase of abstract painting after the 1960s: the elegaic, whose knight errant is Brice Marden. Differently practiced by Agnes Martin and Blinky Palermo, among others, this response to the paralysis of Abstraction l poeticised a sense of being orphaned by the death of a parental tradition.’ Beattie and Harding’s ‘endgame’ shares this sense of melancholy, as does Fiona Rae, whose work made around the time of Schjeldahl’s essay- such as, say, ‘Night Vison’– had a toughness and directness that would surely have made her a snug fit for Abstraction II, but who has, on the evidence of ‘Stairway’s ‘So Perfect And So Peerless’ replaced her cheeky Pandas and sometimes seductive, sometimes bruising colour combinations with rather polite and elaborate brushy flourishes in pastel hues that hover between the decorative and the gestural, listlessly floating over a white field.

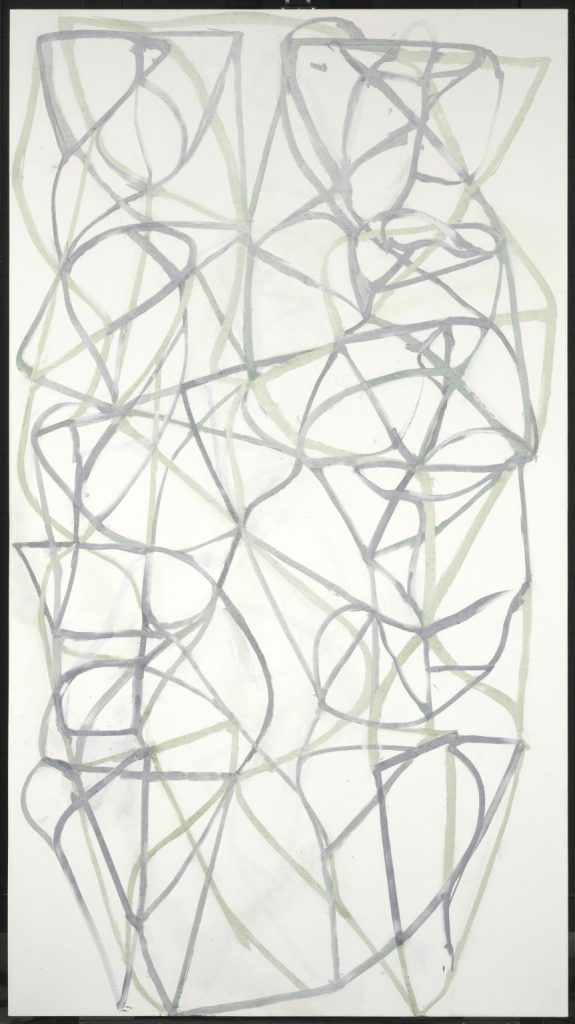

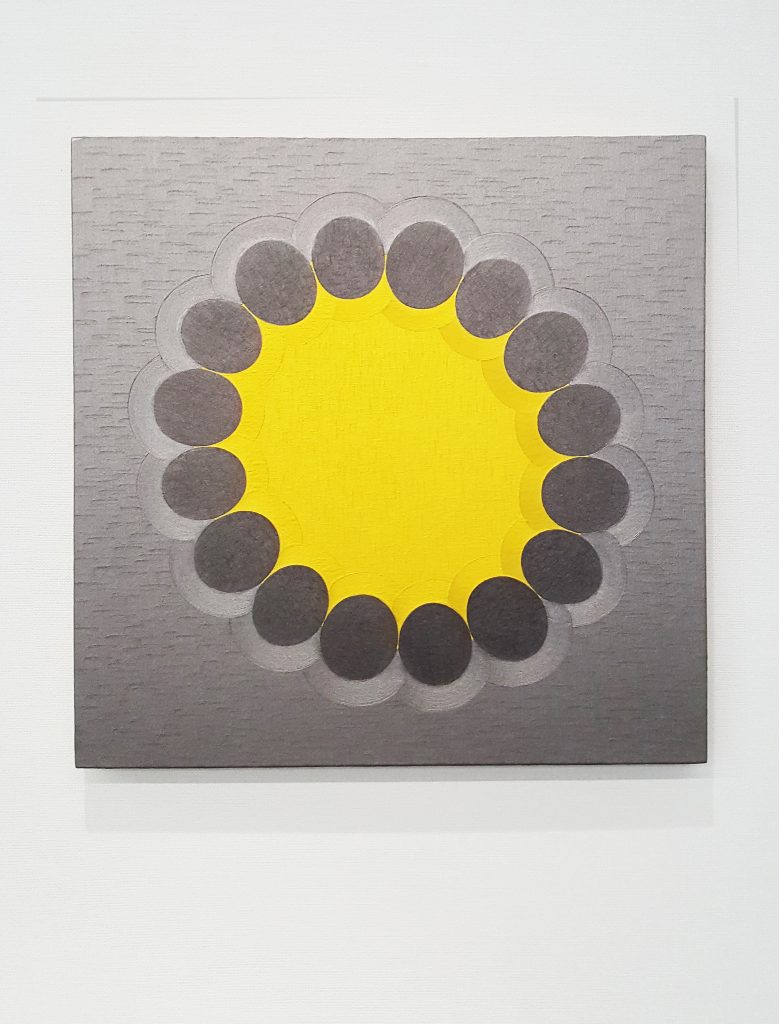

Phoebe Unwin, Jane Harris and Luke Dowd all partake of the ‘elegaic’ mode also; Dowd’s gridded pieces, in particular, feel slightly ‘low-fi’, slightly homespun, deploying reductive modernist tropes in a manner that recalls Agnes Martin, distilled within a ghostly haze of rasterized dots. It is Jane Harris, arguably, who has put this mode to best use, honing an exquisite tension between hermetically sealed, reductive abstraction and the blatantly decorative. She harnesses a sumptuous array of golds, silvers and other hues, invoking the lustre of the luminous enamels of icon paintings or heraldic insignia through careful orchestration of shape and colour. All of this mourns Schjeldahl’s ‘death of a parental tradition’, in ways that suggest that these artists look back through ‘Abstraction II’ to something lost in ‘Abstraction I’, and that such a perspective gives rise to work that feels ponderous rather than provocative, supine rather than searching.

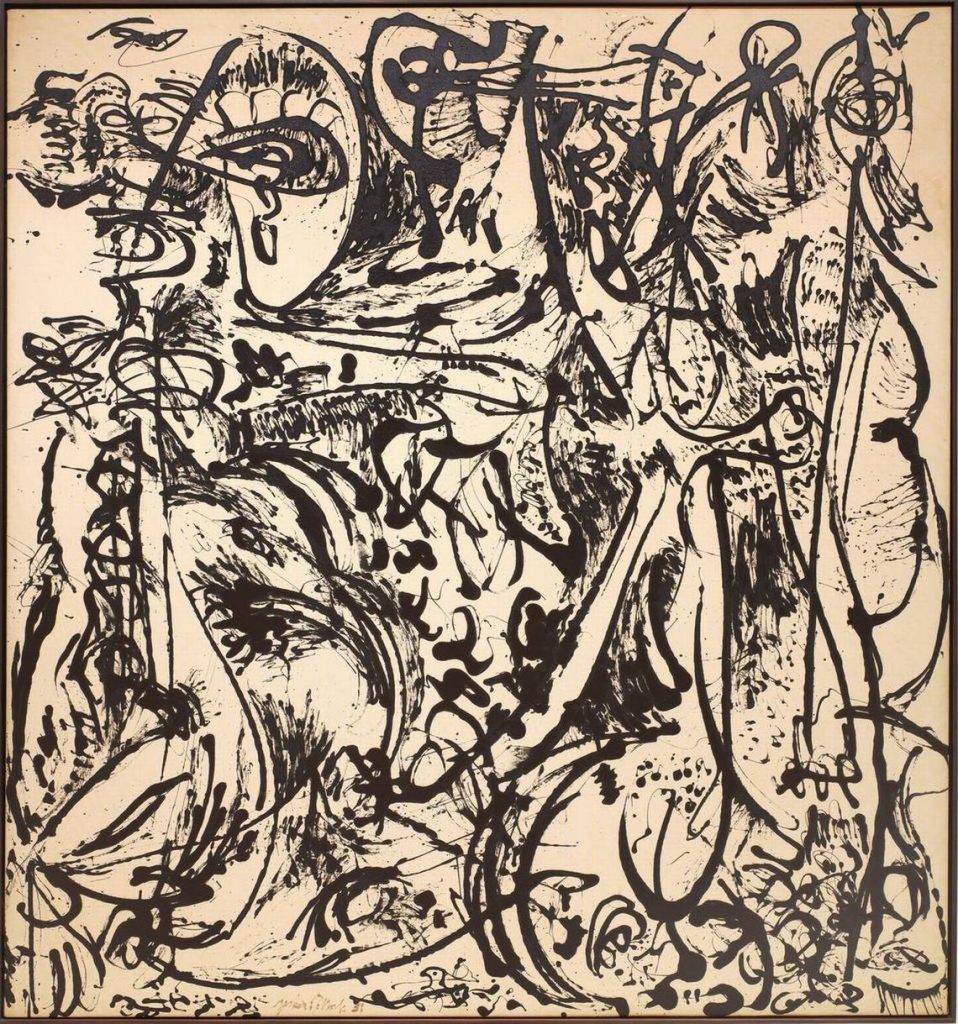

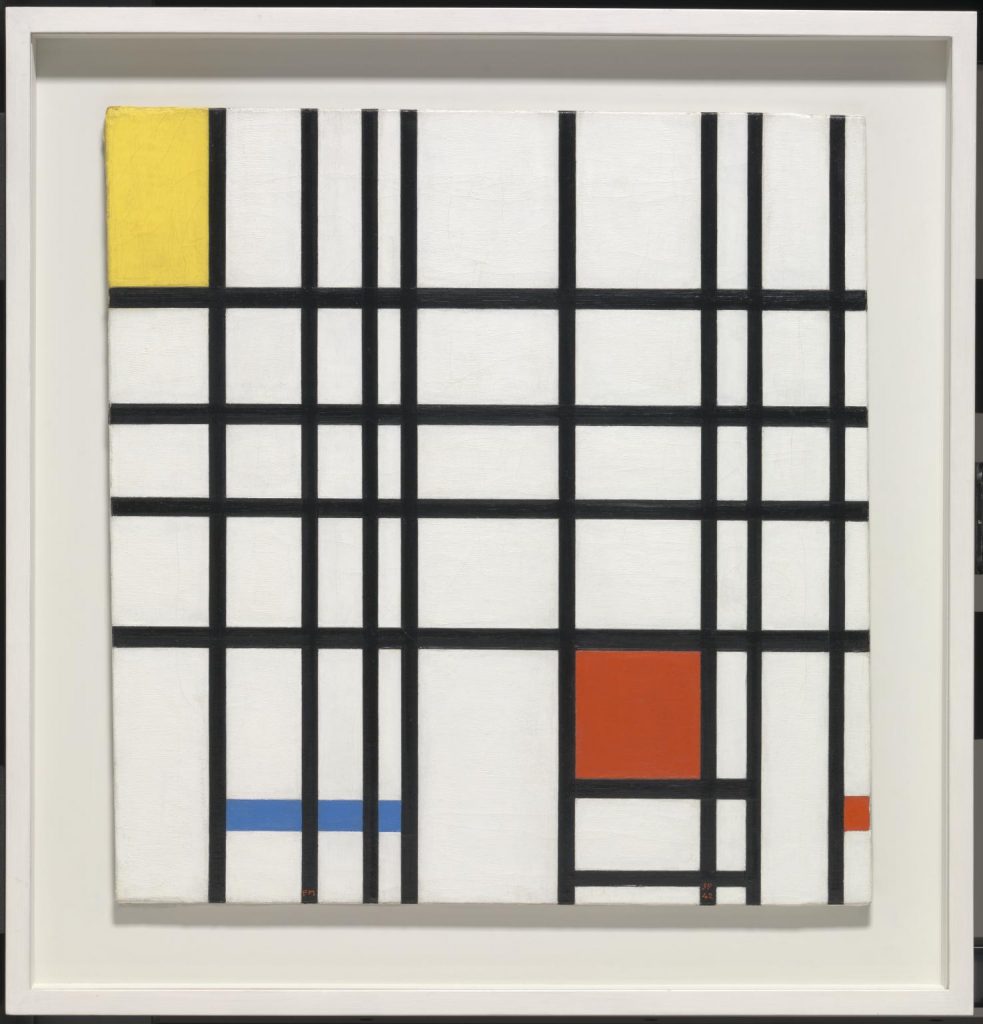

So, what was it that was lost with the passing of ‘Abstraction l’? For Schjeldahl, ‘the crowning feats of Abstraction l’ were not, as ‘Stairway…’ seems to propose, the heroics and histrionics of a journey into the Great Abstract Unknown, but ‘those of Piet Mondrian and Jackson Pollock- (who) introduced systems of marking that are so far removed from normal figuration that they practically circle round to reinvent the figurative from scratch.’ In Mondrian’s painting ‘we behold universal dramas of the horizontal, to which gravity tries to reduce everything, and the vertical, which defeats gravity(…) Mondrian expresses a universal condition of earthly existence, an ur fact that we grasp with our brains and feel in our guts.’ Pollock, meanwhile, takes us to the far reaches of the expressive potential of paint on canvas, both high and low: ‘what (one) get(s) from a good Pollock drip is roughly and inextricably (1) the music of the spheres and (2) a dog pissing up a wall.’

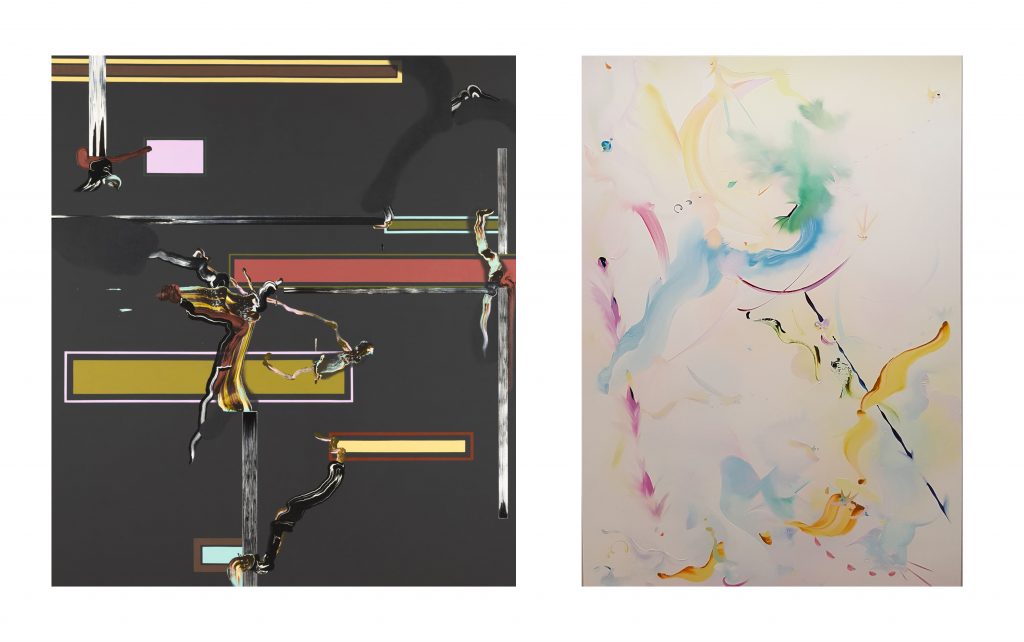

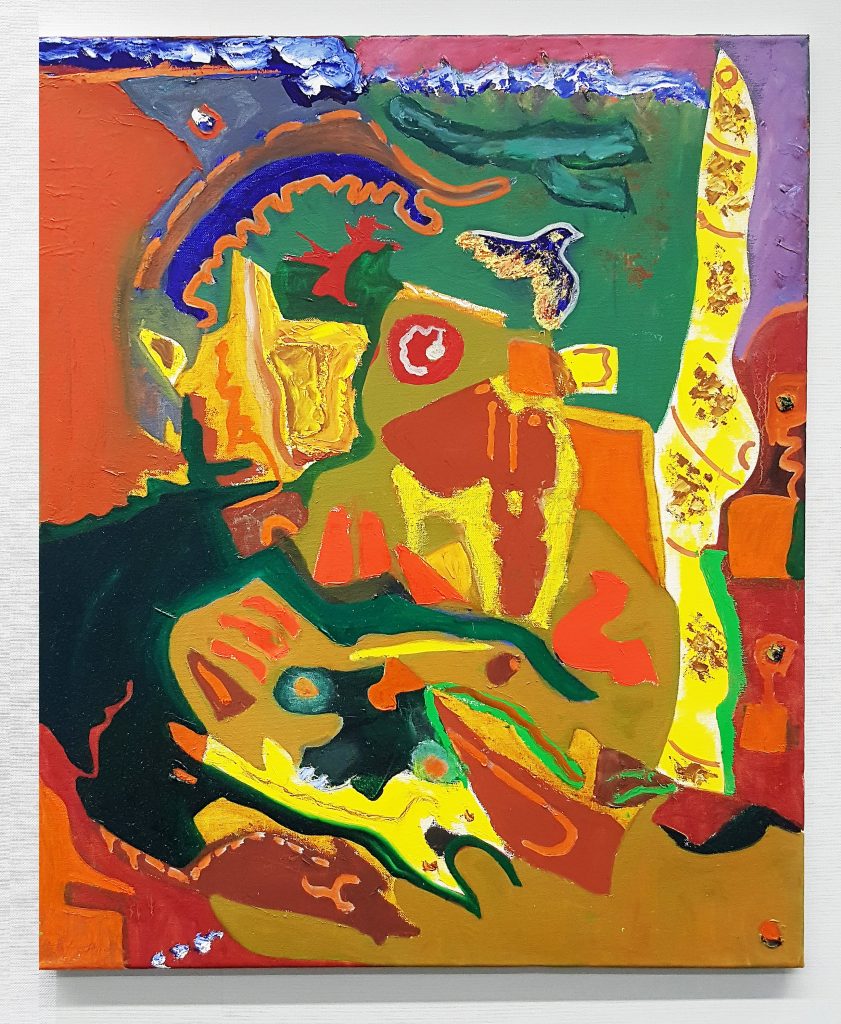

If the influence of Pollock and Mondrian is to be found in ‘Stairway…’ then it lies in the cubist syntax which dominates many of its more exciting stylistic tropes; taking us back, arguably, to a time that predates even ‘Abstraction I’. What Pollock and Mondrian shared was the need, in their respective historical contexts, to challenge and work through the potentialities and the pitfalls of Cubism, and thus, by default, the influence of Picasso. Pollock had famously lamented, ‘That fucking Picasso…he’s done everything!’ and Mondrian’s studious avoidance of a meeting with the Spanish Master, for fear of falling under the spell of his charisma, is well documented; and for his part, Picasso’s disdain for all things abstract is equally notorious. And if all of this feels far distant, remember, Schjeldahl has been at pains to point out that this history ‘is not only not over, it has reawakened after fever dreams of history.’ ‘Stairway’s…’ Mark Wright, Dan Perfect, Wendy Sullivan, Caterina Lewis, Phillip Allen and Rannva Kunoy have found a Schjeldahlian ‘petri dish in which things can grow’ in the fertile soil of the no-man’s-land between figuration and abstraction, between cubism and Pollock, where Picasso, Braque, Gris, Picabia and Duchamp had dragged painting by the scruff of its neck; that same neck that the last two artists on the list had attempted to wring soon after.

But painting’s neck refused to be wrung, of course. The oft-repeated maxim ‘That which does not kill me makes me stronger’ would seem to work as well as a motto for painting as it does for people; and perhaps this is the key message Schjeldahl sends from the recent past into our present. Of all the artists he writes about in his generous, inclusive essay, he has this to say: ‘In each case something of the wide world- some vernacular tone or maverick sensibility- has flown in through the studio window and been caught in paint, where it propagates. This is the reverse of so-called Postmodern appropriation. Instead of incorporating bits and pieces of received cultural debris into their art, these painters turn over their art wholesale to an inclusive sense of culture.’ Painters who are prepared to wholeheartedly welcome the introduction of Schjeldahl’s ‘choice contaminants’ will be best placed to revivify their art form; rather than finishing it off for good- the implicit or explicit aim of so much Postmodern art- these ‘contaminants’ can actually serve to strengthen painting’s ailing immune system.

Have the artists in ‘Stairway…’ taken this lead; or are many of them still imbibing from the ‘ineffable bottle’ of ‘Abstraction I’? In ‘Abstraction II’, Schjeldahl proposes, ‘Pragmatism rules. That which succeeds needs no theory. Theory without successful work is dead. The measure is human satisfaction.’

‘Human satisfaction’ in what sense? In summing up the importance of Mondrian and Pollock- his two pathfinders of ‘Abstraction l’– something becomes a little clearer about what he is looking for in ‘Abstraction ll’. In Mondrian he finds an ‘earthly existence’: intellectual aspiration, certainly; but something of the bodily also. It’s not about the Theosophical texts or the vagaries of a spiritual quest: it’s about the interactions of the horizontal and vertical as they work across the picture plane, and the role they play in augmenting our sense of sight and thus our sense of place in this world. Granted, Schjeldahl talks about ‘the music of the spheres’ in relation to Pollock; but he follows that with a reminder of Pollock’s determination to push at the limits of painting through the use of extreme materiality and physicality that are very much of this world. Schjeldahl contends that abstraction’s worldliness has always been present, but suppressed by ‘Abstraction I’s utopian ambitions, political posturing and avant-garde theorizing; for him, ‘Abstraction l’s ensuing identity crisis is the very well-spring of the renewal that surges up in ‘Abstraction ll’. ‘Stairway’s…’ Gary Webb offers us a measure of this Schjeldahlian ‘human satisfaction’: his sculpture has taken Schjeldahl’s irreverent attitude to history and optimism about the future and run with them. ‘Buzios’ splices moulded plastic reminiscent of futuristic 70’s furniture with the High Modernist precision of Caro’s table pieces, minus the table. By turns humorous and sleek, the subtle play of biomorphic surrealism, cool, sinuous lines and rich colour are reminiscent of ’70’s-inflected Art Nouveau, with a dark ‘Clockwork Orange’ undertow. Knowing, Postmodern kitsch? Perhaps not: Webb’s ‘contaminated’ content seems to add up to more than the sum of its parts. As one walks around the piece, the sculpture reveals itself with a satisfying visual lyricism all its own.

Whether we adopt Schjeldahl’s framework, ‘Abstraction l’ and ‘Abstraction II’, or remain ambivalent about such polemics and prophesising, his essay subtly points to the constantly shifting nature of the sands on which contemporary abstract artists now build. He also poses the crucial question: whether abstraction should attempt to provide a ‘stairway to heaven’, a ‘gateway to the unknown’ or ‘guide to a spirit world’. Ironically, the most challenging art in Coombs’ ‘Stairway To Heaven’ suggests instead how abstract art might be a way to apprehend more directly what it is like to be on this earth, to be right here, right now; and how it might allow us to reconnect with those most complex of sensations with a renewed intensity and vigour.

‘As viewers of abstract painting, we are invited to be experimental agents of humanity, testing on ourselves certain propositions of how our species operates. This was true of Abstraction l. Different now is a humbled attentiveness to what people actually and darkly are, not what they ideally and brightly ought to be.’

‘The Rise of Abstraction ll’ by Peter Schjeldahl appears in the catalogue for ‘Abstraction Once Removed’ 1998 Arts Museum Houston USA ISBN 0-936080-44-2

‘Stairway To Heaven: Abstraction Now’ runs till Oct 18th 2019. Viewing by appointment only. Contact SKainth@wfw.com for details.

Phillip Allen, ‘Fly on The Wall to Fly in My Soup (Version 1)’ (2014), indian ink on canvas, 183 x 183 cm

Luke Dowd, ‘Colour Chart 1’ (2012), acrylic on canvas, 160 x 120 cm

Francis Picabia, ‘Mariage Comique (Comic Wedlock)’ (1914), oil on canvas, 196.5 x 200 cm

Pablo Picasso, ‘Femme à la Mandoline (Woman With a Mandolin)’ (1910), oil on canvas, 91.5 x 59 cm

Agnes Martin, ‘Friendship’ (1963), gold leaf and oil on canvas, 190.5 x 190.5 cm

Brice Marden, ‘Study for the Muses (Hydra Version)’ (1991-1997), oil on linen, 211 x 343 cm

3 thoughts on “John Bunker: ‘That was Now, This is Then’”

Comments are closed.

Lovely essay. Chris Bucklow’s ‘What is in the Dwat’ on Guston has some interesting thoughts on Abstraction 1 as a quest for unity and the nature of Guston’s disruptive reaction . But when polarities are created it’s sometimes interesting to imagine a rapid oscillating between the poles, rather than making a choice; so that although they are separate, a vibration is set up, and I got a kind of sense of this here. (Hope that’s not too obscure!)

Wonderful, John! Thank you for a fascinating read!

Whilst I find this essay enlightening, especially the idea of abstraction being figuration by other means, and beautifully written, John comes a Greenbergian cropper with his employment of Scheldjahl’s empty rhetorical phrase “human satisfaction”. I confess to being a European and a Lacanian, and of course in Lacanian terms, the human is constituted by lack, and it is this lack that allows the perpetuation of desire. Whilst John for example might cite Mondrian’s paintings as constituting “human satisfaction” I would say it is more revealing to consider the power of Mondrian’s works in terms of their “lack”. As we all know, representation cannot match reality; so asking a painting to constitute human satisfaction is contradictory – an idealist gloss. It’s not hard to see where this comes from – standard American 60s positivism, the American dream, the idea you can have what you “want”. A pragmatic materialism: “what you see is what you get”.

The history of post-war painting hasn’t followed this programme. By the 1980s, painting was snatched back by Germany, where the puritanical truth-to-materiality ethos of Greenberg was set spinning again by European scepticism. Where is the “human satisfaction” in Polke and Richter? Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say that rather than providing satisfaction, they are teasing the viewer?

When John refers to abstraction II he simply means American 1960s abstract art. But the distinction is false. Different painters embody different subjects. Im Sweden in the 1890s people may have embraced Theosophy. In New York in the seventies, Brice Marden embraced Zen and mindfulness.

The crucial issue here is to try to avoid making art about art. Art is not a closed system, but a mirror to reality. Any kind of formalism, be it abstract formalism, theoretical formalism, or political formalism replaces reality with a tautological, false mastery. The point is to embody a subject, a position, a point of view. Abstraction is no different from figuration in that sense, though how any form of painting fits into society is anyone’s guess.

John wants abstract art to show us what it means to be “right here, right now “. But perception is always split between subject and object, subject constitutes lack, and the experience of being present to life is always momentary. These are sobering insights from psychoanalysis that perhaps constitute a counterbalance to John’s idealist positivism.