Charley Peters: ‘Painting, Writing, Abstraction and the Spaces In-between: In Conversation with Tess Jaray’.

Instantloveland is delighted to present the first of three commissioned pieces by ‘Writer-in-Residence’ Charley Peters: ‘Painting, Writing, Abstraction and the Spaces In-between: In Conversation with Tess Jaray’.

Charley Peters (b.1973) was born in Birmingham, UK and now lives and works in London. Starting from an interest in the legacy of hard-edged abstraction, her work considers the manifestation of painterly language in the context of contemporary visual media. She is concerned with the spatial potential of the painted surface, on which she applies subtle variations in colour, tone and scale to construct illusionary light and structural depth. Peters harnesses the materiality of paint through layering, opposition and juxtaposition, exploring the disrupted syntax of pictorial composition synonymous with our experiences of reading space, substance and abstract form in the post-digital image world.

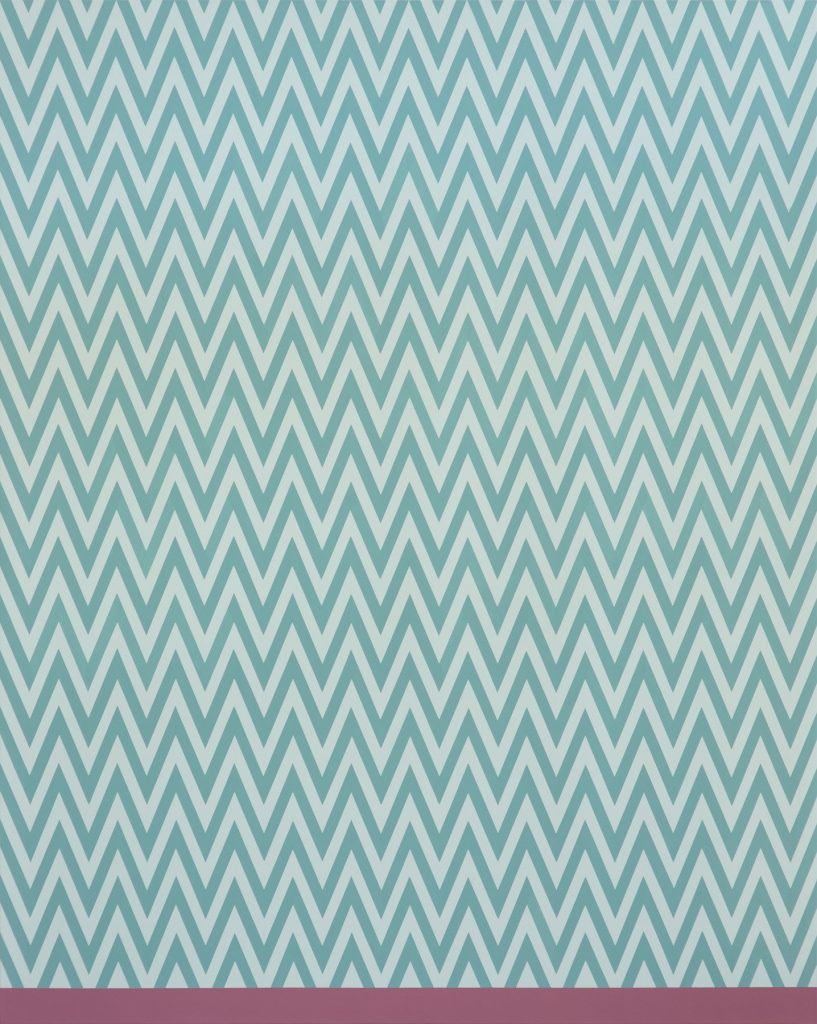

Tess Jaray (b.1937) was born in Vienna, Austria and moved to UK in 1938. Examining the geometry of pattern, repetition and colour within her surroundings, she has explored painterly perspective for more than five decades. Jaray focuses on producing the illusion of space, using perspective to create a field of spatial paradox that equates to distance and closeness in the mind. In many of her works the area of pattern is contained by a strong, grounding background colour, thereby controlling the movement of the forms. She currently lives and works in London.

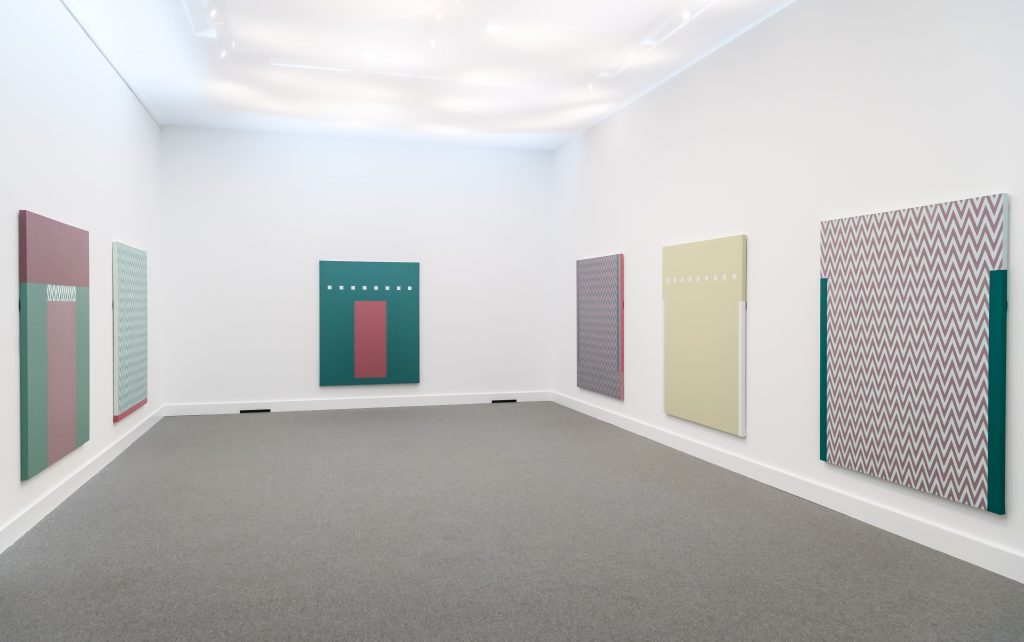

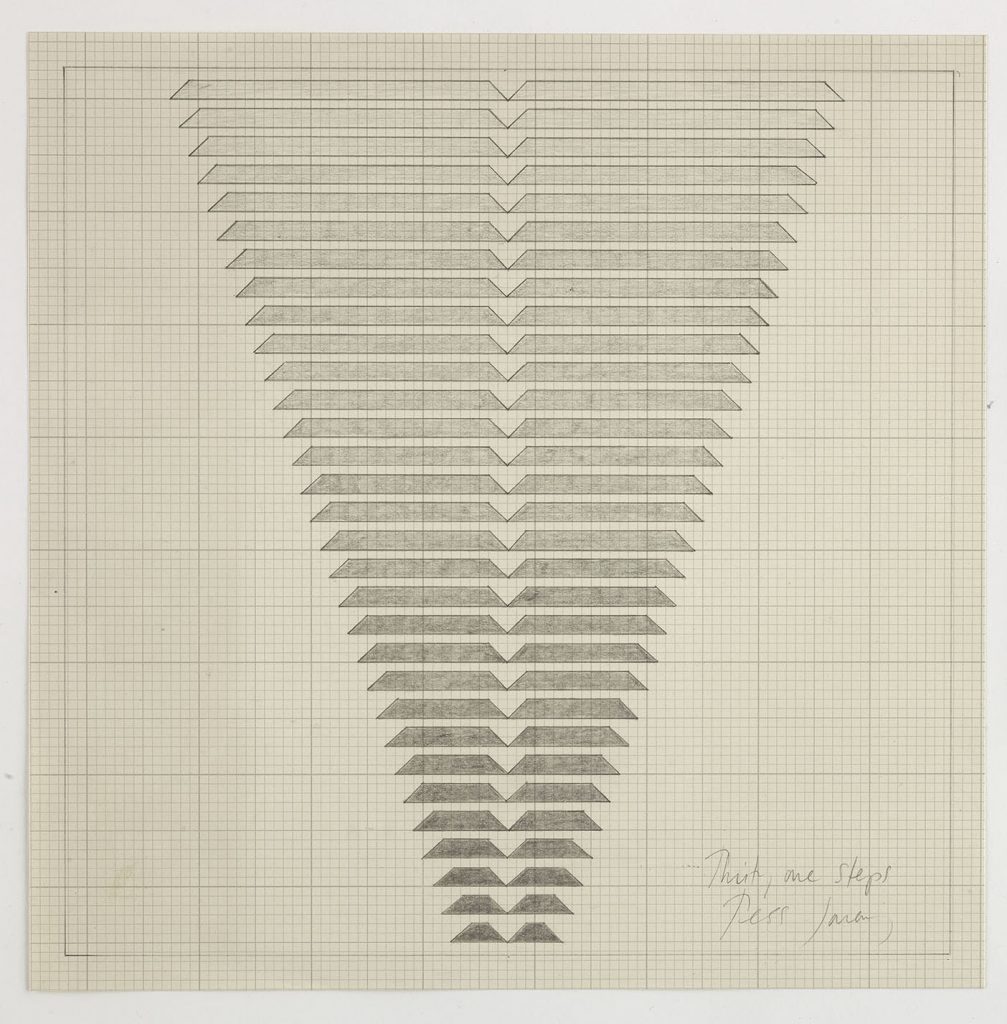

‘From Outside: Tess Jaray’ is a presentation of six new paintings at The Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham, on display until 12th May 2019. Using the Art Deco building of the Barber Institute, designed by Robert Atkinson and built between 1932-1939 as a Foundation for the works, the paintings extend Jaray’s ongoing contemplation of architectural form and continue her rigorous evaluation of the emotive conditions of spatial composition through carefully considered, desaturated shades of green, pinks and off-whites, and repeated geometric motifs. Hung close together and low to the ground in a room that was remodelled specifically to house the works, they present as both a coherent series of paintings with shared formal concerns, each maintaining a unique identity defined by subtle variations in colour and pattern, and as an immersive physical environment of bodily, human-sized canvases. The exhibition is supported by a selection of Jaray’s drawings, from graphite on paper studies made in the 1960s to digital drawings made in the past 10 years, that show working methodologies, experimentation and enquiry, and a skillful exploration of the ambiguities of space and compositional structure.

I met with Tess in her studio in North London the month before the exhibition opened. We spoke about her work for the show, wider concerns in her practice and the nature of painting itself, and continued the conversation by email, extracts of which follow.

—

Writing as a painter

CP: Talking to other painters about what they do and how they do it stirs as many questions as it provides answers for; questions about what I do myself, how it could be better, what is important to hold onto in my own work and what I could afford to let go of. I’m interested in how you negotiate the relationship between painting and writing as an artist, as it’s necessarily a straightforward one. If you’ll permit me to beginby reflecting briefly on my own experiences of writing, then that will hopefully lead into a consideration of yours in relation to mine: how they differ, how they coincide.

These days I paint more and write less; I find the former activity far more favourable than the latter. When we met in February, one of the first things that you said to me was that you love writing, yet the more I consider things, I tend to think that I dislike it. It’s a difficult, too-logical process that leaves me fidgety and distracted. I’m actually writing this now in the studio, in between applying strips of masking tape to a new canvas, because that’s the only way I know to put words together that make sense. I try to reconcile the difficulties of writing by thinking of words as colours and textures that sit next to each other to make some sort of resolved composition of text. When I paint, my usually noisy mind is somehow quietened, thoughts and words come ‘in between’ painting for me, and not as an activity themselves. Where my writing is full of caffeine and headaches, yours feels diaristic and fluid, it is precise yet also lyrical – gestural, almost. It is clearly the writing of a painter. Writing invariably comes from a different place than painting, and when we are asked to write about our own work or provide a contextual location for it, it’s easy to slip into literalisations and illustrative descriptions that limit the work rather than allowing an autonomous reading of it. What I enjoy about your writing is its capacity to provide a context in which the work can breathe and continue to grow; you don’t present a universal truth but instead, your own truth. When it is difficult to articulate what we can see or feel when we look at artworks – as it sometimes is when a formal language is used in painting – your writing is situated in a unique place between the scholarly and the subjective, with the concerns of the studio at the centre of the texts at all times. Could you describe your approach to, and relationship with, writing, and how you position it within or alongside your painting?

TJ: You would probably be shocked, if not horrified, by my lack of concern with where I ‘position’ my writing in relation to the painting. I really don’t do that any more than I ‘position’ my domestic chores or tying my shoelaces. Somewhere it is surely all connected, but we give different values to different activities. Probably not always correctly…as a painter so much of oneself is centered on the activity itself, so much concentration and searching and desire – desire above all perhaps – that any distraction from the central issues of making a painting seem somehow artificial. Once you start asking what the world thinks of what you are doing you are laying yourself open to something that should only come later, at the point at which you put the work into the world. By which time you will have made irrevocable decisions, for better or worse, that you probably have to stand by. Underlying it all, of course, is what one might call an unreasoned obsession. No reason in the world could keep anyone doing it, in the face of general social disinterest, over an entire lifetime.

With writing it’s very different, or so it seems to me. Partly because I’m not attempting anything seriously ambitious, not competing with Proust or Tolstoy, so if there are failures that’s fine, I just delete them or admit to imperfections. With painting there is really no halfway house, you have to try to get it right. You might fail, but I’m not certain that a painting can be ‘half right’. With writing you have that useful tool, a narrative, so there is always something there even if it’s badly expressed. Of course I do sometimes feel that narrative painting has that advantage over ‘abstract’ painting. You can always see if it’s a dog or a tree, though it’s no easier to make a great narrative work than one with no apparent narrative. But as most things get more interesting the longer you look at them, perhaps the tree or the dog will suggest thoughts or memories that are in some way enriching? Abstract artists don’t have that luxury, in some ways they are trying to see the world without support.

Oppositions, decisions and in between spaces

CP: You have described painting as ‘a coming together of the head and the heart’, which I can completely relate to. It’s difficult to say where decisions come from in the process of painting – from experience and reason, the intuitive compulsion to just ‘do’ or somewhere in between. I try to reject logical thought as much as possible in the studio, preferring to do things because they feel right, or intriguing or challenging visually…or often because they feel problematic or wrong somehow. I enjoy using opposites: implied viewpoints from both above and straight on in the same painting, solid colour next to stark diagrammatic lines, flat paint next to areas of illusionary pictorial depth, precisely painted hard edges broken by more rapid gestures. I see opposition in your work too, ‘in-between states’, voids and spaces that are difficult to define absolutely. You describe physical space on the canvas but there are unspoken spaces too – the space in-between intention and interpretation – for example, rectangles that have the uncanny property of doors or windows without representing them. In the paintings that you have made for ‘From Outside’ you establish relationships between the inside and outside of the building, the work is both spatial in its image properties and in its being as a physical encounter. The hang feels very sensual, and despite the dynamic visual energy in the paintings – the repeated chevrons that cut across the entire width of some of the canvases – there is a notable ‘stillness’ in the work and in the way that we encounter it physically. Its low positioning on the wall allows the paintings to not just be ‘seen’ but also experienced in relation to our own bodies; the works surround us as an architectural intervention as well as being architectural explorations on a pictorial plane. Could you talk more about the work and how it developed as a series of paintings, and also speak a little about the decisions made around the presentation of the work in the gallery?

TJ: First of all, I’m not at all sure that my description of painting as ‘a coming together of the head and the heart’ is quite right. (That’s one of the problems of writing being published, your mistakes are set in print…) The more I work and the more I reflect, the more I realize that the head really has less to do with the whole creative endeavour than one would like to believe. Perhaps it would be truer to say that it’s a coming together of the heart and the hand, with a quick check-in at the head. The mental organization – I really don’t want to say ‘intellectual’ – is probably on the same level as doing anything that needs some concentration, cooking potatoes, writing a letter, planting a tree. I suspect that you are more aware of your process than I am. You say that you ‘try to reject logical thought as much as possible in the studio, preferring to do things because they feel right, or intriguing or challenging visually…’ whereas I suspect I just go into auto-drive, and am not aware of any logical thought processes. Perhaps they are just hidden from me, or perhaps I just don’t have any. But it’s worth remembering that no-one, ever, has been able to define what the creative process really is and how it works. That’s partly what makes the whole thing so fascinating, because we all think, at certain moments, that we have understood. And it’s true that there are, probably for all creative artists, of whatever style or belief, and however good or otherwise, those amazing moments – and they never, never last – those moments when they understand why they are trying to do what they do, even if they don’t achieve it. Perhaps that is the miracle of the birth of anything.

You describe some of the aspects of the paintings on show at the Barber, for instance as ‘‘in-between states’, voids and spaces that are difficult to define absolutely’, probably rather better than I can. I suspect this is because we cover some of the same territory in our work, and you can identify in some way with mine. And identifying is different from observing or even appreciating. It gives you an insight, something familial. As when I looked at the images of your paintings I recognized the journey you are on, although of course can’t possibly say where that will take you.

Very many creative artists have spoken about ‘searching’ for something. Picasso, of course, famously said ‘I do not seek, I find.’ So when you say you try to reject logical thought, that is probably the same thing. When I was a young artist I used to secretly feel I was like the monkey at the typewriter hoping to come up with ‘Hamlet’. Now I can understand that unless we try to enter uncharted territory the work will just be academic. I’ve just looked up ‘academic’ and the dictionary says ‘not of practical relevance, of only theoretical interest’. I am not remotely interested in theoretical interest. What I am seeking is how to gain a new experience from the familiar.

When you say that my ‘rectangles (…) have the uncanny property of doors or windows without representing them’ that is very much what I aim for. I could say that I am referring to doors or windows, but that would not be strictly true. We can of course only see those things around us in terms of our own bodies and our own scale. The world from the point of view of an elephant or a fly is pretty different. At least I imagine so. But it’s also worth remembering that the experience of looking through a window or walking through a door is never, ever, the same, however many times it is repeated. So repeated experiences can be simultaneously familiar, therefore calming, and new, therefore stimulating.

The chronology of drawing and colour

CP: One of my favourite essays in ‘Painting: Mysteries and Confessions’, is ‘Green.’ It is also one of the most-used colours in my own paintings.You describe it as ‘a colour painfully longing for a subject’ and oppose its infinitely extendable qualities with its unpopularity in abstract painting – it is commercially unviable and remains in the shadow of its natural friend, the landscape. You understand colour so well, asis displayed through both your painting and your writing, and despite its subjective and emotional nature your palette is consistently fearless but balanced. You have spoken to me about how you make drawings in order to resolve a composition; and then, once this process is complete, you ‘allow’ colour. This is different to how I start a painting, which always begins with colour, and drawings – usually rough and barely intelligible scribbles – come later while I’m painting, scrawled quickly on scraps of paper as I sit on the studio floor. I find several things about your relationship with drawing and colour fascinating. When we talked in your studio earlier this year you described drawing as ‘a means of finding yourself’, you use drawing as a way of thinking through potential paintings and making decisions. It seems that without drawing, no paintings would be made, and so it is especially exciting to see a collection of your drawings on display at the Barber Institute at the same time as your paintings. The drawings on show that you made before 2010 are graphite on paper, rendered precisely and assuredly in greyscale. Colour seems so inherently at the heart of your work that it’s difficult to imagine it being a secondary consideration, as these drawings might illustrate. The works made later shift to digitally generated drawings, rendered on Adobe Illustrator and made into material objects as unique inkjet prints. These do include colour, which presumably has been selected very deliberately from an almost infinite amount of variations available on screen. I wonder if using digital technology has allowed your relationship with colour to change? Has the capacity to draw digitally and visualise both form and colour at once brought these two elements closer together in terms of how you then conceive a painting? Colour seen on a screen is very seductive but accurately rendering backlit colour physically as a print or through painting is difficult. Are there now two different languages of colour present in your work, the virtual and the actual?

TJ: Well I’m sorry you mentioned green. Because ever since I wrote about it green has popped up in rather unexpected paintings. So it seems that I got that at least partly wrong. You only have to think of the dress in the Van Eyck ‘Betrothal’. But perhaps it only goes to prove that whatever can be said about paintings, often the opposite is just as true…

I am impressed that you always start with colour in your paintings, because in spite of all the exhibitions we have seen with titles such as ‘The Colour of Form’ or ‘The Shape of Colour’, the fact remains that there isn’t really such a thing as isolated colour. Every colour needs to relate to something, even if it’s just the four edges of a canvas, which makes the idea of ‘purity’ of colour very difficult to understand, let alone to use. Perhaps that may be why you are attracted to opposites, in order to create a tension?

And what you say about digital colour is true. Very interesting and very challenging. Artists have always been attracted to innovations in technology, and the digital leap has been massive. As with so many of these things there are advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand almost all colour is available to us with a click. Which is incredible, when you think what it takes to mix colour on a palette. And as you say, when backlit on the screen it’s very seductive; but when it’s printed out it loses that quality and becomes mechanical and even inert. I haven’t yet seen any ‘digital’ art that replaces the handmade or hand-printed. But maybe that’s a problem for my generation. I think that nothing can replace the touch of the hand. Which takes us back to the relation of the head to the heart to the hand…but as a tool and a resource the computer is incredibly useful and I use it all the time to test my responses to relationships of colour, and sometimes just simply to find a colour.

The newness of ‘Abstraction’

CP: I’m interested in what ‘abstract(ion)’ is or means today. I have a feeling that it might be a term that we don’t need anymore, other than to position work historically. Perhaps abstraction was only ‘abstract’ in the past when it was challenging or difficult to decode, but now I think it’s a familiar visual language, seen as logos, icons on computer desktops, and screensavers of blended colour fields. Specifically, on screens, which many of us spend a lot of time looking at each day, we see the formal signifiers of abstraction alongside other forms of visual or textual information, often within the same visual register. Our contemporary understanding of pictorial space is complex, we are used to seeing multiple ‘windows’ at the same time – on computer screens, smart phones and digital tablets – fluidlyexperiencing a constant stream of pixelated, disconnected images as the commonplace way of encountering visual culture. Abstraction has shifted into a more easily known space. So, is your work still ‘abstract’, and if so, how does it maintain this identity within the context of a presentation of work such as ‘From Outside’, where the influence of architecture becomes a primary lens though which to see the work? In your lecture for the Slade Contemporary Art Lecture Series in 2015-16you talked about ‘everything coming from something’ and this brings me back again to your writing, which is generously authored and positions yourself in your work in a way that I find less comfortable to do myself – I wonder if sometimes ‘abstraction’ is used as a term intended to filter out subjective, emotional or bodily experiences. Do you think that terms such as ‘abstraction’ become more or less relevant in how we see painting at different times? How do you situate yourself within defining terms such as the ‘abstract’ and has this changed throughout your career? And if it’s possible to say, can abstraction offer us anything new? We have talked about how we can’t invent new shapes or patterns, and maybe we never could. What are you going to make next?

TJ: Those are all seriously interesting questions, and need a larger forum to answer than we have here. You are right, the term ‘abstraction’ has changed, in use if not in understanding. As you say, there are so many logos, icons etc that refer to nothing but what they are advertising, which is what it seems to come down to. It does point to the power of shape and to some extent colour, to refer to something that has a more or less single meaning. Of course, there have always been such things as flags, which proclaim a country, or an identity, which go unquestioned. But now there are thousands of shapes which do more or less the same thing, and have become part of a new use of visual language. Abstraction as sole signifier.

When I started painting, which is some sixty years ago (help!) abstract simply meant non-figurative, non-representational, not referring to the ‘real’ world. Perhaps that is why my painting so often didn’t quite fit into what was required at that time, which was a particular take on Modernism. In the sixties abstraction was more acceptable if it could be seen as formalistic, with no referential meaning outside itself. Many artists of that time were more interested in such things as the behavior of formal devices, the use of colour to make shapes advance and recede, without asking for any other meaning. It was of course a new way of looking at painting, much of which came from American Abstract Expressionism, and was very exciting. To discover, or perhaps understand for the first time, that a colour such as yellow could be expansive, seemed at the time like a great innovation. And worth remembering, that the age at which an artist makes such discoveries is crucial. The impact of something learned at twenty is going to be very different from something new learned at sixty, with so much prior understanding to relate it to. You cannot overestimate the importance of context. Where, how and when something is first experienced.

But I needed something more, something that touched at a deeper level than the visual. And this is something that goes back to what you say about the difficulties of saying where decisions come from in the process of painting. If I can say anything useful about this at all – which I can’t really – it has to do with trying to find a way of keeping in touch with those things that really touch us, that really seem to matter. Those infinitesimal things that are so hard to notice in every day life. To notice, for instance, when walking down a street, that you might look at the red doors and I at the blue ones. That you might prefer dusk and I dawn. Neither is right or wrong, but they signify something of our own desires. When I’ve found a way to do all this right I will let you into the secret…in the meantime it has to be rather hard work and an insatiable need…

—

‘From Outside: Tess Jaray’ is on show at The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham until 12th May 2019