Eye Opener: Alan Gouk

‘Eye Opener’ is a new feature on Instantloveland. We have been asking artists who work with abstraction to write about an art event- whether it be a single artwork, exhibition, installation, time-based piece or performance of any kind- that has had a significant and lasting impact upon them. First up is British artist and critic Alan Gouk….

Boredom is the catalyst that draws one to art. In Glasgow on rainy Sundays the Kelvingrove Art Gallery (not the Italian cafes with their juke boxes and frothy coffee) offered some respite from the tedium of ‘life as it is’.

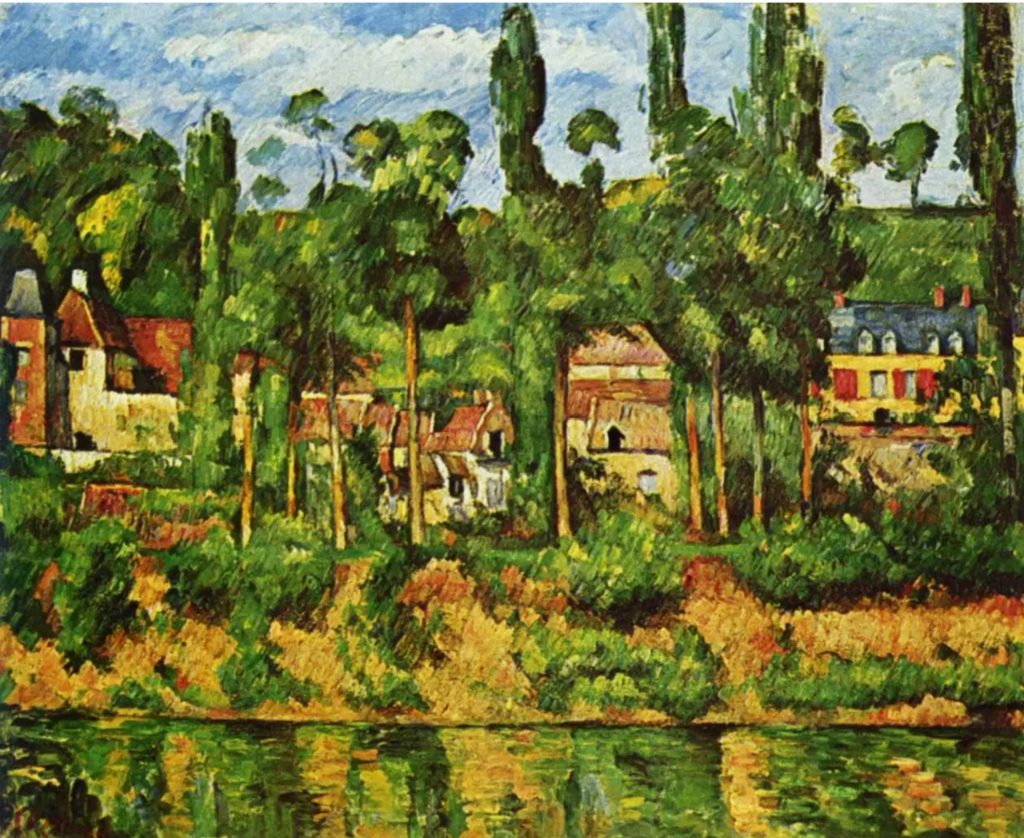

I would go past the suits of armour and weapons, the glass cases full of model ships and stuffed animals, up the broad staircase to the brightly daylit Impressionist galleries, where the aroma of furniture polish and wood preservative combined with the imagined scent of turpentine and pine trees that seemed to exude from the landscapes, above all from Cezanne’s view of Zola’s house at Medan (from the opposite bank of the river). There were other delights too — a Gericault Horse, the Monticellis, but I seldom ventured further back in time than that.

And later, in 1958, when I had read John Rewald’s little book on Cezanne, his life and work and friendship with Zola, and learned more about the cantankerous loner personality of the man, his paint-spattered clothes and his fear of being touched, his image formed a template of all that it means to be a true painter.

The painting itself (now in the Burrell Collection) has imprinted itself on my sense of what a painting is; echoes of it recur even in my ‘Gaucin Night II’ of 1992 — the uprightness of the low relief modelling, lack of recession, the rhythmic semi-diagonal slapping of brushstrokes of the river bank and bushes forming a repeated pattern throughout the picture, the buildings half-submerged, interrupted and contradicted only by the horizontal reflections in the surface of the river itself, to avoid the vertiginous effect of a mirror image in the water.

Possibly it was the year before reading the Rewald book that I had decided on a watercolour sketching holiday, cycling and youth hosteling on the Isle of Arran, alone, of course. On one occasion I set up my portable easel on the shore of a small inlet and was diligently trying to copy reflections in the water and a small fishing boat. I was approached by a family, a retired banker, his wife and children, who, taking pity on my stoicism, offered to take me out fishing for mackerel in the little boat, and then back for tea at their house nearby. (The mackerel leapt onto the hooks in droves).

These were the terms of my vision of painting at that time — nature, landscape and Cezanne, and a Wordsworthian immersion in nature as depicted in his poem, ‘Nutting’, at that. Only Cezanne now remains. How is that possible, you may ask, when the first two terms are inseparable from what Cezanne is? Beneath the astringent, acerbic and ascetic control of the means, there bursts forth a burning, suppressed sensuality that is pressed into the service of form through the eloquence of the slapping and stroking of paint in accumulating flurries and mounds that are no longer just paint — a delirium in the paint, not just in the mind.

I have tried to evoke and commemorate some of this in the group of paintings — ‘Afternoon in Naples’, of 2017-2018 — not in any sense a transcription from the original (in Canberra), but just an attempt to marry my own involuntary response to surface, and my own rhythmic patterns, with something of the sensual poetry of the original.

By the time I had committed to being a painter and embarked on a second sojourn in London, I was in thrall to the Abstract Expressionists, mostly from reproduction in books such as Skira’s ‘Contemporary Trends’. The big event of 1964 was the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation’s exhibition, ‘Painting and Sculpture of a Decade 1954–64’, at the Tate, curated by Lawrence Gowing, Alan Bowness, Ronald Alley and others.

Designed by Peter and Alison Smithson to fit into the unpropitious cavern of the Duveen Gallery, the pictures hung on screens lit by high level spotlights; this gloomy installation did no favours to Rothko, Gottlieb and De Kooning. (I wasn’t so interested in the British contingent, although Roger Hilton’s ‘The Aral Sea’ did impress). The painting that stood out for me was Clyfford Still’s ‘PH 847’ (1953), with its torn curtain cliffs of palette knifing.

Although not hung strictly chronologically, the impression was clearly given that the Ab-Exers had been superseded, and that the hot news lay with the American Pop artists (this was the bias of the selectors, it seemed). The labyrinthine hang had somehow found its way into the main galleries (I think), where firstly British pop, and then Johns, Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, Rosenquist, Indiana, Dine, Wesselman, Warhol and Lichtenstein held sway.

Those of us who had been painting out of the Abstract Expressionists were momentarily knocked sideways, and there then followed the big shows of Rauschenberg and Johns at the Whitechapel soon after.

For about six months I dabbled with Pop Art-ish paintings which endeavoured to combine Matisse’s ‘The Conversation’ with Pop influences (à la Wesselman, I suppose).

There have been later surveys of this kind, purporting to encapsulate a zeitgeist. Beware both of the influence that they have over the impressionable young, who always feel that the only way to be ‘in the swim’, to be ‘current’, is to latch onto the latest thing, and of the motivations of the organisers. Though stylistic fashions may proceed apace, the immediate foreground seeming to preclude access to the riches of the past, it is only by digging deeper that one will find one’s way to that ‘main current, that does not always flow through the most established reputations’— to paraphrase TS. Eliot.

Comments are closed.