John Bunker: ‘Bodily traces, darker spaces and hang your dirty washing out on the line’: Amy Sillman, ‘Landline’ at Camden Arts Centre

Amy Sillman, detail from ‘Dub Stamp’ (2018), a series of double-sided acrylic, ink and silkscreen works on paper, 152.5 x 101.5cm each, photograph courtesy Damian Griffiths

I look at stuff from ancient Egypt, and I also look at now…I don’t think about it as art history—I think about it as art. People live with everything at once, including the future.’1Battaglia, A, ‘A New Painting Exhibition, ‘The Forever Now,’ Opens at MoMA,’ Wall Street Journal, Dec. 12, 2014.

These words of Amy Sillman’s, quoted in a review of the 2014 exhibition, ‘The Forever Now’, take on a palpable reality in ‘Landline’, at the Camden Arts Centre. There are a set of painterly processes at work here that actively engage with notions of chronological time, and its interplay with works of visual art, in interesting and contrasting ways; and the show has been cleverly curated to reinforce this aspect of the works on display, exploiting the circuitous nature of the gallery spaces to full effect. As to what these notions might consist of, Andrew Benjamin may be able to provide a clue: in his book ‘What is Abstraction?’ he suggests how time itself complicates, and might even nourish, our understanding of abstract painting:

‘ Instead of viewing each abstract painting as a unique and self enclosed work, the work of pure interiority, there must be an allowance for the possibility that part of the work, and part of its own work as a work, will be a staged encounter with earlier determinations and thus forms of abstraction.’2Benjamin, A (1996) ‘What is Abstraction?’ p38, Academy Editions.

This notion of the ‘staged encounter’ rings true of Sillman’s approach here, in the various connected galleries at Camden Arts Centre. But it is not only the encounter with aspects of abstraction’s histories that counts; it is also necessary to consider the relationships forged here between painting and other media, such as film, drawing, screenprint and zines;3Zines are small-circulation self-published works of original or appropriated texts and images. ‘In the Central Space Sillman’s back catalogue of self-published zines is available for visitors to buy, including the latest issue -OG#13- created especially for Camden Arts Centre. Sillman’s zines often intervene discursively or diagrammatically in her exhibitions- branching out from the painting into her personal relationship with a subject…’ Camden Arts Centre information sheet. and also between abstraction and figuration.

1. Sparbüchse [Coin lady], 2016, Unglazed ceramic, 44 x 35 x 18 cm, Courtesy the Artist and Capitain Petzel, Berlin with a back catalogue of the OG (#1 – 2; #5; #6; #11; #12), Self-published zines available to buy for a one-unit coin (£,$ ¢), photograph courtesy Damian Griffiths

1. Pink Drawings, 2015-16, Acrylic, charcoal, and ink on paper, 76 x 57 cm each, photograph courtesy Damian Griffiths

The installation piece ‘Dub Stamp’ (2018) in Gallery 3 consists of a series of images produced in the first few days after the election of President Trump. The stringing-out of these images, in the manner of a washing line, heightens the sense of immediacy, narrative and improvised decision making; it also plays on the public-versus-private, the domestic sphere, and the hanging out of one’s ‘dirty laundry’ in public. Echoes of bodily processes such as copulation, ingestion and excretion proliferate. The ‘double sided’ nature of the installation adds another level of references: on one side, there are minimal drawings of the same stick-like figures that appear as ghostly apparitions in the paintings hung in the other rooms, here dragging their distended teats across the floor and vomiting black bile from their impossibly thin and dishevelled bodies; the other sides of these suspended sheets, by contrast, are far more complex, fragmentary and colourful, with intermingling elements of screenprint, paint and drawn line. These dual processes of emptying-out and re-complicating evoke Jackson Pollock’s trajectory, as he moved from Jungian archetypes to the near-total abstraction of his complex ‘all-over’ masterpieces; finally returning to dark, overtly figurative imagery in the disturbing ‘black paintings’. These new lands that Pollock and other pioneers discovered are now familiar, farmed-out territory; and Sillman tips all this tired history on its side, bringing dark humour to bear on the conventions of abstract expressionism- its haptic materiality and dynamic improvisation- in many of her film and zine images: Charlie Brown meets Melanie Klein via an internet-savvy primitivism.

Amy Sillman, detail from ‘Dub Stamp’ (2018), a series of double-sided acrylic, ink and silkscreen works on paper, 152.5 x101.5cm each

But there is a group of paintings spread throughout the Camden Arts Centre’s Gallery 1b and Gallery 2 that includes ‘In Illinois’, ‘TV in Bed’, and ‘Lift & Separate’ (all 2017-18), works that seem to hold all this narrative potential for action in suspension. The elasticity and graphic dynamism of the cubist-like spaces that Sillman is well-known for are diminished here, and replaced by a recurring motif consisting of two floating humanoid forms; it feels almost as if the light waves emanating from the relatively heavy oil pigments have slowed down, or gone into reverse, giving a sense of light being sucked back into the paint surfaces rather than rushing out toward us. Many of the paintings seem to reveal themselves in slow motion, while the drawings and films whir at speed around us.

In ‘In Illinois’ (2017-18), the whole structure of the painting rests on the splitting up of architecture-like spaces. A complex set of gridded-off, slanting verticals of demarcated colour opens up the space of the painting, despite the muddy density of the paint. A coldness formed from the abutting of the blues and greens pushes down on a looming window of milky, fog-like violet ground, within which two comic/abject figures’ outlines are suspended, one floating awkwardly above the other. These stick-like bodies are attached to one another by a taut pink umbilical cord that stops the suspended one from just floating away. It’s as though two cartoon ghosts have appeared in the lower section of a Diebenkorn ‘Ocean Park’ and are haunting and diverting the march of progress: that process of innovation and constant refinement that is the hallmark of these famous works, and of late Modernist abstraction in general.

Of course, Diebenkorn is well known for his nervous switching from abstraction to figuration: along with Guston, de Kooning, Hartigan and the later Pollock, he was instrumental in creating a different agenda for painting- what Greenberg dismissed as ‘homeless representation’. And it’s the ‘homeless’ stick figures that antagonize the abstractness of Sillman’s paintings here. Mostly acrylic paintings, like the beautifully taut ‘The Innie’ (2017) and ‘Edge of Day’ (2018) still push at the dynamic cubist spaces opened up via the body by the likes of Duchamp’s ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’ or Picabia’s various games with painterly languages, sex and a machine aesthetic; but here, though, in works such as ‘Lift & Separate’ (2017-18), Sillman seems to be embracing oils in a move toward a heavy painterliness which has more in common in terms of surface (though not of scope) with the neo-expressionism of Baselitz and co. If anything, though, it’s the humour created by the tensions between a painterly pathos and bathos that might connect this group of works to certain Guston paintings from the 1970s, such as ‘Waking Up’ (1975).

There is very little pomposity, self-pity or self-aggrandisement here. Somehow these awkward, denser works in oil encourage us to look back upon them as though they were ruptures in time, as a gradual, alienating freezing of temporal progression; even as accumulations of images locked like fossils in rocks. These paintings suggest both the historical time of painting, through their allusions to the history of abstraction; and a lost time of action, an irretrievable moment of being-in-the-painting that is vulnerable and human. Still, there is nothing sentimental about lost time here; neither is there any dried-out historicism or parody overtly at work. Sillman’s harking-back from our image-saturated era to the 1st-century poet Ovid’s ‘Metamorphosis’ might help us consider the stream of art and culture that flows unstoppably as images and materials tumbling into one another, from the past into the future and back again via the internet, carrying us along with it. It is interesting how these paintings feel both of their time and somehow outside of it: in the body but not of it.

Those parts that bore some moisture from the earth

became the flesh; whereas the solid parts –

whatever could not bend – became the bones.

What had been veins remained, with the same name.

And since the gods had willed it so, quite soon

the stones that man had thrown were changed to men,

and those the woman cast took women’s forms.

From this, our race is tough, tenacious; we

work hard – proof of our stony ancestry.4Metamorphosis of Ovid. (Book.Line). (1.407-415). Allen Mandelbaum translation (1993). This citation refers to the original Latin. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

‘Landline’ at is at the Camden Arts Centre until 6th Jan 2019.

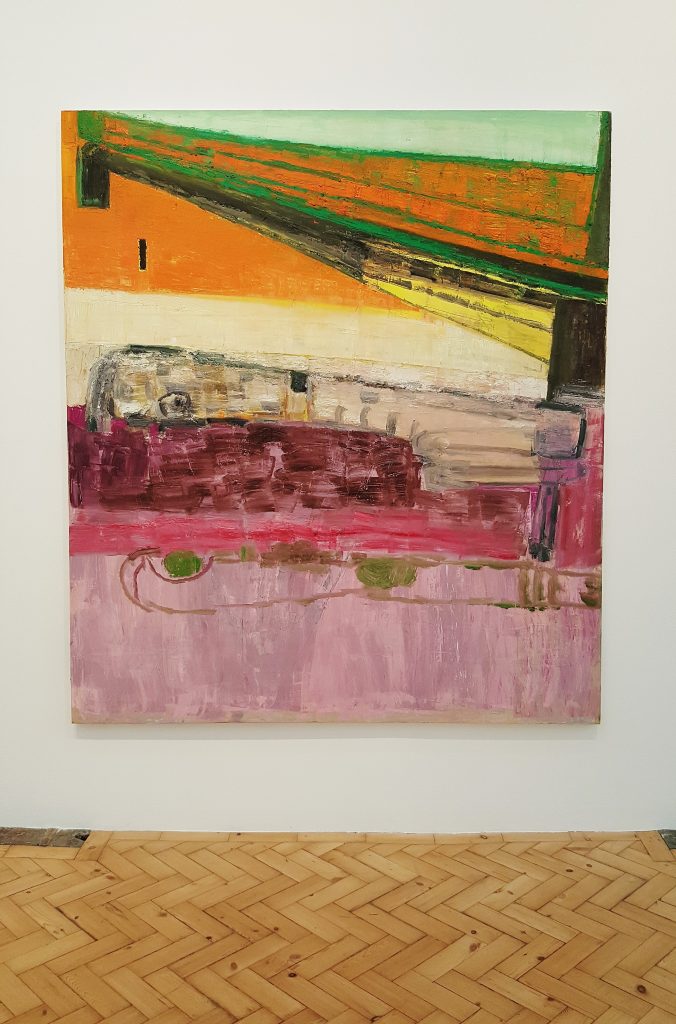

Amy Sillman, ‘TV in Bed’ (2017-18), oil on canvas, 190.5 x 167.5cm

Amy Sillman, ‘Edge of Day’ (2018), oil and acrylic on canvas, 190.5 x 167.5cm

Amy Sillman, Installation view of ‘Landline’, Camden Arts Centre, 2018

Amy Sillman, ‘Avec’ (2017), acrylic on canvas, 129.5 x 124.5cm

Amy Sillman, ‘Kick the Bucket (Loop for Portikus)’ (2016), still from HD video, 16:9, 10 mins (Loop)

Amy Sillman, Installation view of ‘Landline’, Camden Arts Centre, 2018, photograph courtesy Damian Griffiths

One thought on “John Bunker: ‘Bodily traces, darker spaces and hang your dirty washing out on the line’: Amy Sillman, ‘Landline’ at Camden Arts Centre”

Comments are closed.

Thanks for the reminder of this rich and weighty show. I experienced the ‘Dub Stamp’ washing line as a hang of teatowels, covered in sick, no longer fit for purpose. I wondered whether some of the figures were necessary or if they threw compositions offbalance or, rather, diminished the affect of the split spaces. Otherwise, ‘Avec’ is a champion effort of shoving everything to one side to create space. Thoroughly worthwhile exhibition.