Lisa Sharp: Orbiting ‘The Field’

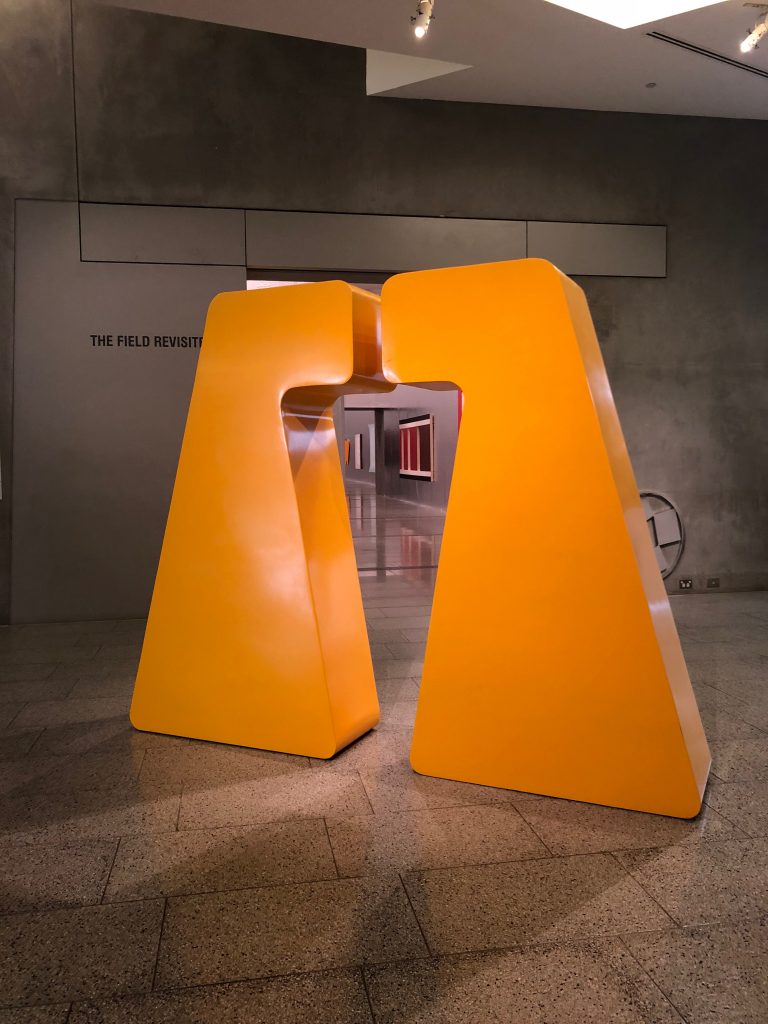

Installation view of The Field Revisited, National Gallery of Victoria (Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia), 2018

Something big happened in Melbourne for Australian art and artists recently when the NGV opened its bright and shiny trove of an exhibition, The Field Revisited1National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), The Field Revisited, 27 April – 26 August, 2018. This was a re-staging of The Field of 1968, an exhibition at once famous and infamous in the history of Australian art. It remains one of those controversial and mythic moments variously and retrospectively described as seminal, landmark, defining, breakout, mythologised,2John Mcdonald, ‘The Field Revisited: Mythologised exhibition reconstructed at NGV’ even as one of the most revered offerings in Australian art history.3Sharne Wolff, ‘Revisiting The Field’, 20 December 2017 Soaring walls lined in silver wallpaper formed a dramatic backdrop for the display of the originals, a roll-call of many (now) well-known artists and works. While The Field had been brave and new, it hadn’t been acquisitive, and after the exhibition the works were scattered.4The silver walls are worth a mention. For The Field, 1968 they were silver-covered screens, the idea of John Stringer, Exhibitions Manager and inspired by his visit to Andy Warhol’s studio in New York. The curatorial premise is visually intrusive, it annoyed some artists and to some extent, situates the exhibition space itself as a self-contained installation. After 50 years, the NGV was able to locate and exhibit 62 of the original 74 works of painting and sculpture. Interestingly, where works remained lost, they were afforded the same physical space they would have occupied, had they been found, by the inclusion of life-size facsimiles of the originals.

As an exemplar of colour-field, geometric and hard-edge paintings and their sculptural counterparts, the NGV exhibition did not disappoint in their revisitation. From the moment of encounter with the assertive stance of Wendy Paramor’s Luke, a gleaming, juicy yellow threshold of a sculpture positioned by the entrance, the works were all lucid, confrontational statements about the visceral effects of looking closely at colour, form and surface. The energy of the new hadn’t dissipated at all, but was still present; palpable in the vitality of the work, in the clarity of form and colour, in its craftsmanship, and the communication of its ideas. The works had aged well and were a pleasure to experience, as art history up close.

The Field successfully showcased a singular direction and a particular moment in abstraction in Australia.5‘It is biassed (sic) to define one particular direction in contemporary Australian art. It concentrates on the abstractionists, and further restricts itself to an aspect thereof, which one is reluctant to confine by terminology. But the words, hard edge, unit pattern, colour field, flat abstraction, conceptual and minimal have been used.’ Brian Finemore, Curator and John Stringer, Exhibitions Officer, Introduction, The Field, Exhibition Catalogue, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1968, 3. Carrying out its remit as a national gallery, the NGV represented a group of youthful and emerging artists of the age (half were under 30 and not many had held solo shows). It was 1968, and they were playing with, and fluently plying, the purely visual language of abstraction, arguably at the height of Formalism, offending many, yet supported by the institution. Anyone who has borrowed or leafed through the highly sought-after, largely black-and-white catalogue of the 1968 show would have delighted in the form and colour bursting from the walls in 2018, and in being able to assess the material heft, weight and scale of the works in person. Beyond the silver-lined inducements of the gallery, however, other aspects of this restaging were more problematic: of the forty working artists selected in 1968, only three were women. So, as Sydney Ball’s conspicuously anachronistic double door-sized painting Transoxiana (reproduced on a tote bag for the Revisited show) seemed to be doing – let’s ask the loaded question – why do it, why revisit?6Sydney Ball, Transoxiana, (1968), acrylic on canvas, 203.2 x 145.1 cm, reproduced on tote bag, 43 x 36 cm, $12.95 available NGV Design Store.

Overwhelmingly apparent is the fact that with Revisited the NGV was looking back, its close-lens focussed on delivering an exhibition which, while forensically accurate – and perhaps even a little nostalgic – was fundamentally historicist in outlook; meaning that the gallery was neither considering the contemporary moment in abstraction, nor the vision, decisions and ramifications of its predecessor. A lost opportunity as far as the NGV was concerned; but one seized by a number of artist-run, as well as commercial galleries, which staged so-called ‘unofficial satellite’ shows that orbited The Field Revisited, hosting an enormous diversity of contemporary abstract work.7Zara Sigglekow ‘The Field Revisited: A Guide to its unofficial satellite exhibitions’ in online editorial Art Guide Australia, 3 May 2018. Their very presence outside the institution offered an implicit critique, haunting the NGV show as spectres in much the same way as the lost works of The Field haunt The Field Revisited.8Although the curatorial intent may have been to acknowledge the powerful presence of absence, The Field Revisited’s inclusion of lost works as reproductions is salient. Recreated 1:1 in grey scale, these pictorial enlargements of the catalogue images stand as monumental pixelated sentinels, hinting noticeably at the absent issues that are not addressed by the NGV.

Col Jordan, Daedalus – series 5 (Redux) (1968, remade 2017), synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 167.6 x 335.3 cm

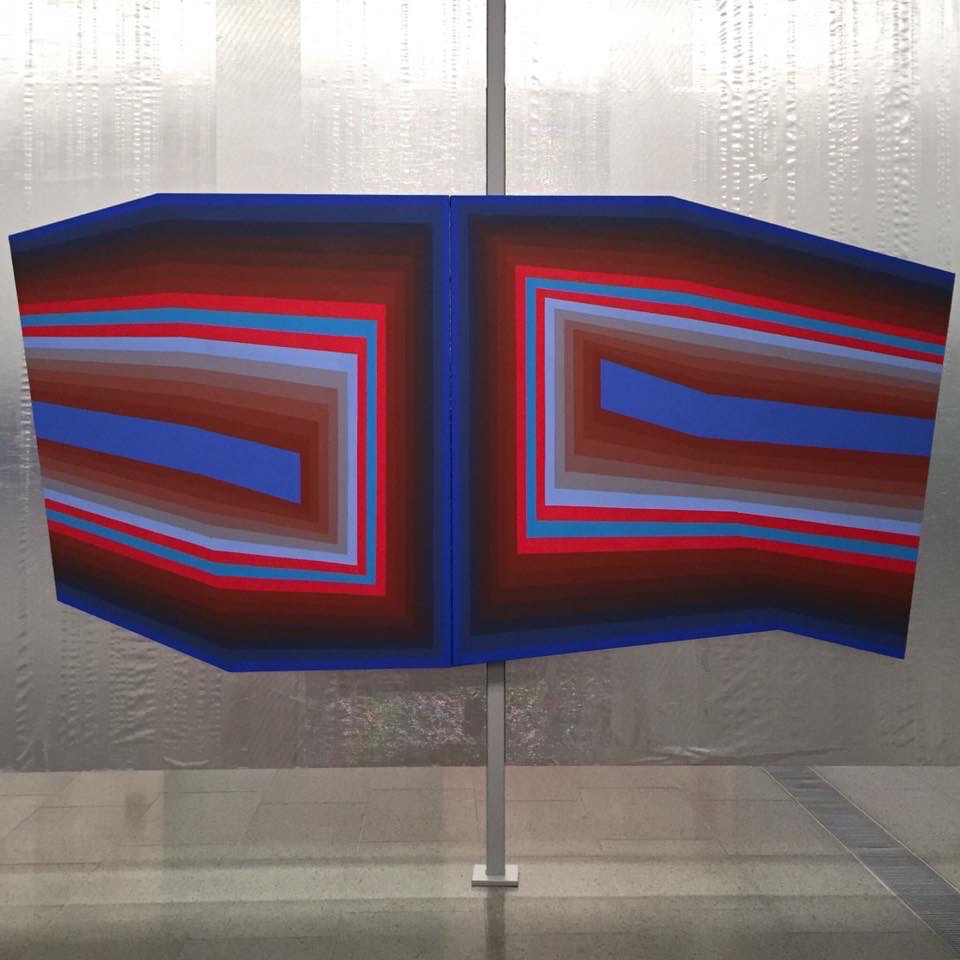

The Field came early on in the careers of several of its participants, who are still making work within the tenets of Modernist abstraction. A few were interviewed or otherwise took part in The Field Revisited’s opening weekend talks. Col Jordan, whose brightly–lined, angular shaped canvasses are at once optically seductive and unsettling, recently remade both a sculpture and one of his Daedalus series of paintings after they were destroyed in a house fire. Jordan continues to paint with bright colour and hard edges, and lately with smaller, tonal and more intricate patterning. He recalled the invitation to participate in the 1968 show, ‘like many others exploring this new direction, it was a vindication that we were doing something important.’9Katrina Noorbergen, ‘Profile: Col Jordan’ in Artist Profile, Issue 42 (March 2018), 103. Ron Robertson-Swann, represented in the show by three predominantly vertical paintings in which colour fields divide and subtly shift the interior pictorial space, went on to build a career as an influential artist and educator, continuing to engage with the spatial effects of geometry and colour. Michael Johnson’s The Field paintings are still as solid as posts and lintels, their units of motion and modularity mobilising flat slabs of blue against black; as pairings, one is angular and dynamic, the other heavy and static. After The Field, Johnson painted for a time in a more lyrical and gestural manner, with thick tube-squeezed lines of oil paint, yet his oeuvre remained steadfastly abstract, focussed around the effects of colour and composition.

Other Field artists have passed away in the 50-year interim. Robert Hunter (1947-2014) was at 21 the youngest artist. His subtle all-white grid Untitled, 1968 (irreproducible in the original catalogue) sits within an oeuvre of consistent experimentation in the ways of whiteness. Always maintaining his spare visual lexicon of nuance, repetition and fragmentation of the grid, each series of works is generated by its predecessor and anticipates the next. It is timely that an impressive retrospective of Hunter’s works is on show in a space adjacent to The Field Revisited. Then there is the highly regarded Sydney Ball (1933-2017), who at the time of his death was exhibiting his last work at Artspace in Sydney,10Sydney Ball, Chromix Lumina #12, 2016 exhibited in ‘Superposition of Three Types’ 2017, Artspace NSW, 10 February – 17 April 2017 and whose early notebooks were most recently included in the 2018 Sydney Biennale,11Sydney Ball, Black reveal, 1968-9, Modular Sketches and sketchbook exhibited in Biennale of Sydney 2018, Art Gallery of NSW, 16 March – 11 June 2018 in a historiographic showcase of abstraction. Ball designed the exhibition poster for The Field, reproduced on a glass wall in Revisited, and is represented by two large-scaled flat colour-field paintings, the massive Ispahan of 1967 suggesting a larger and continuous pattern undulating beyond the confines of the painting.

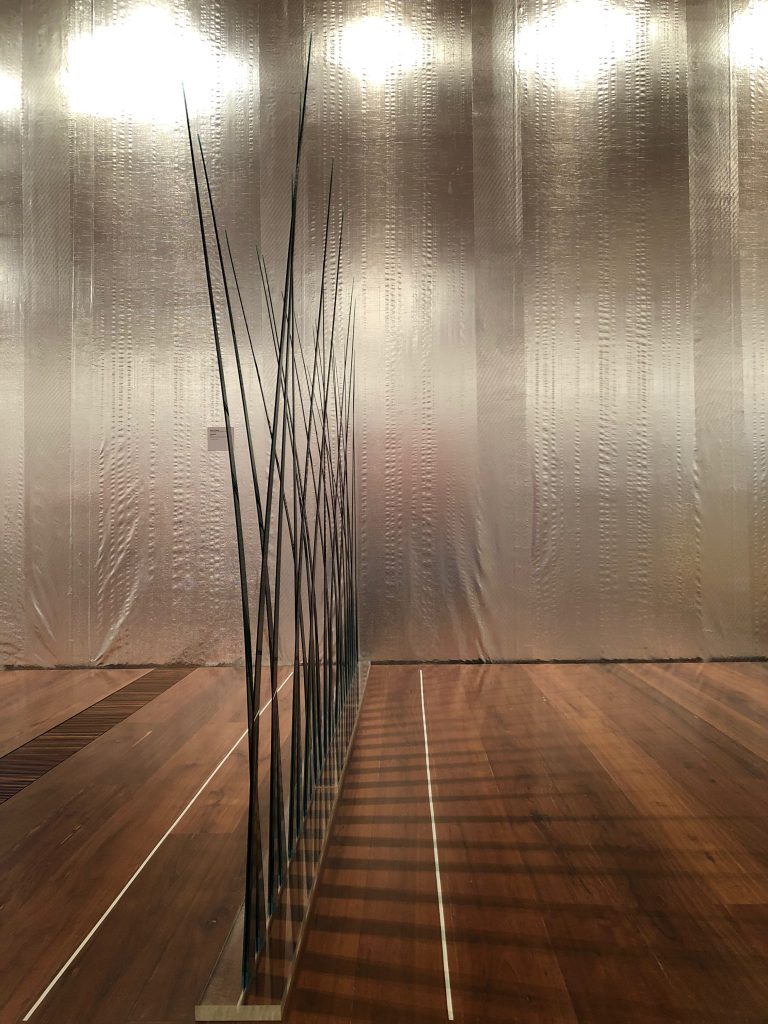

Tony Coleing, Untitled (1968), transparent synthetic polymer resin, 121.9 x 35 x 182.5 cm (variable)

Not all the artists remained in that formalist moment captured by The Field. Tony Coleing, who made elegant, seemingly fragile sculptures of transparent resin and fine aluminium for The Field, recently exhibited digital prints with a strong political narrative.12Tony Coleing, Peking duck duck duck, Utopia Art Sydney, 4-25 August 2018 In his practice, the silent austerity of formalism was replaced by acerbic commentary and opinion. Of the three women artists, all went their separate ways after The Field. Janet Dawson described her works in the show as her last non-objective paintings, and herself as ‘not that much of an abstractionist’, confessing that her underlying and abiding interest was in finding order and structure in painting.13Janet Dawson, Artists on the Field public talk and discussion, NGV Australia, 29 Apr 2018 Wendy Paramor’s last exhibition at Sydney’s Central Street Gallery in the years before her early death in 1973 made her peers uneasy; she showed photographs of her young son Luke, written off as uncharacteristic ‘happy snaps’.14Alan Oldfield ‘Remembering Wendy’ in Paramor: Lost and Found, Exhibition Catalogue, 48 Normana Wight turned from painting to printmaking, from non-objectivity to figuration: most notably, in carrying out a 33-year postcard project as a statement against the commercial gallery system.

So for the artists of The Field the canon of Modernist abstraction was not necessarily an inevitable precursor or even progression; its curators were right in describing it as a biased, directional moment. By failing to do no more than revisiting, the NGV simply entrenched that historical moment, with all its assumptions intact. Significantly, this is not the first time The Field has been restaged or referenced as a point of genesis for other exhibitions – nor is it likely to be the last – reflecting the depth of its apparently unshakeable influence.15Examples of restagings include: The Field Now at Heide Museum of Modern Art (1984), Fieldwork: Aspects of Australian Art 1968-2002 at the National Gallery of Victoria (1982) and Tackling the Field at the Art Gallery of NSW (2009) from larger institutions, Returning to the Field at Sydney Non-Objective (2014), The Paddock: Looking back at The Field at the National Art School (2015 – now an ongoing travelling postcard and Instagram project), 50 years after The Field at Factory 49 (2018) and Beyond The Field (Still), Moonah Arts Centre and Contemporary Art Tasmania (2018) from others. It has been observed that there is a paradox to these endless restagings, suggesting it is a historical moment (or even, a trauma) that has not yet worked out its rightful place. Whilst the trauma of that 1968 moment is arguably multi-faceted (arguments around national identity, provincialism, modernity and contemporaneity recur), one of the most telling is the neglect of women artists. In catalogue statements, the rationale behind The Field Revisited16‘The true legacy of the exhibition is the support of the contemporary, and of emerging artists, that it inaugurated.’Beckett Rozentals, The legacy of The Field, The Field Revisited Exhibition Catalogue, 3617The Field gave us permission to be pioneering and adventurous: to take a firm, assured position in the presentation of contemporary art.’ Tony Ellwood, Field of Vision, The Field Revisited Exhibition Catalogue, 59 was spiritedly defended by both director and curator; yet in the context of contemporary abstract practice, it entrenches the exclusion of women artists. By way of contrast, over on the other planet, the orbiting satellite: Abstraction Twenty Eighteen exhibited 125 artists, over half of whom were women, across five Melbourne galleries.18Abstraction Twenty Eighteen was a suite of 5 exhibition venues, with female:male ratios as follows: Langford 120 (27:13), Stephen McLaughlan Gallery (7:7), Five Walls Projects (18:16), Justin Art House Museum (9:14) and Deakin University Library Gallery Space (3:7), a total of 64:57.

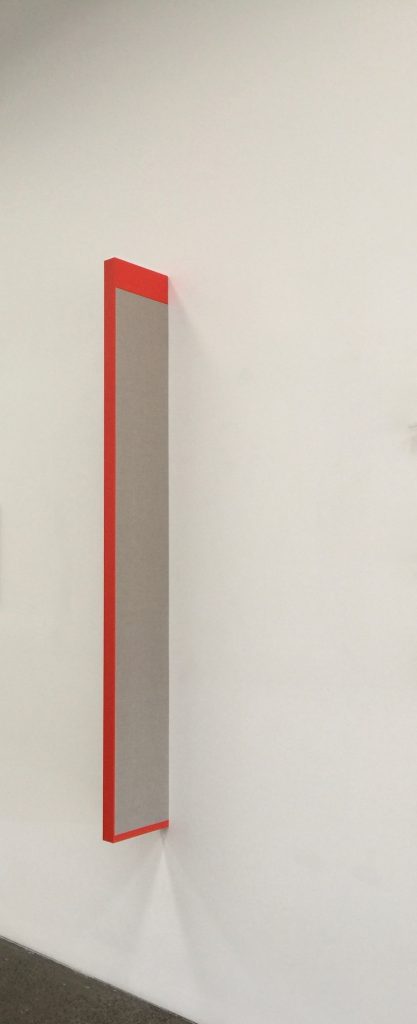

While continuing to utilise its visual language of form and colour, the artists of Abstraction Twenty Eighteen have informed and expanded the formalist vocabulary of The Field with new relationships, readings and systems. This is apparent in many works exhibited by its female artists. Some have been taught by or worked alongside The Field artists and see themselves as inheritors of that 1968 moment and the legacy for them is its continual development. At the Langford 120 Gallery, Louise Blyton showed Long Red Line, a singular work in which the plane of a linen canvas protrudes at right angles from the gallery wall, purposively entering and occupying the exhibition space, led by its opaque red-painted edge. Anya Pesce, also working in red with Small dark red left fold, uses glossy plastic sheets, malleable under heat, now cooled and stilled, that conjure a folding, rippling movement of the picture plane. Both these monochrome works play with traditional hard-edged colour field painting through their sense of movement, defiantly buttressing and softening the hard edges. Marlene Sarroff, who works from the possibilities and structures inherent in found materials, showed a geometric series, Horizontal Progression #1-4, utilising timber offcuts and a restricted colour palette. Hers is a practice finding rhythm, repetition and seriality in the detritus of everyday industry. Similarly, Kate Mackay’s consistent invention, based on the square and the circle, led to her painting series Nothing to say here, a visual rhythm derived from these basic geometric forms. Like bouncing autocues, these provide the pictorial devices to ‘picture’ text quotations from artists and art history, in what could be seen either as homage or critique.

Amarie Bergman, Dittico Bianco E Crema (2017-8), balsa wood, acrylic paint, soap, 2 at 15cm diameter x 8cm; one at 4.4cm diameter x 2.2cm

Matter and materiality are other areas being explored in current practice, opening interpretive possibilities as both source (of often unexpected media, say, of soap or food) and commentary (implicit in this subversion is the introduction of a domestic narrative). Amarie Bergman showed a 2-part work; side-by-side sculpted cylinders of balsa wood and soap, Dittico Bianca e Crema.19Amarie Bergman website https://www.amariebergman.com/blog/posts/13489/dittico+bianco+e+crema At Stephen McLaughlan Gallery Sarah Keighery’s reductive black and white painting is made from formerly edible ingredients: squid ink and salt. In the same gallery, Lynne Eastaway’s work of laminated canvas is presented without the support of frame, appearing to support itself with its own interior structure-as-composition, in the process drawing attention to the textile characteristics, of weave, cut and selvage while incorporating paint and colour as devices of counterpoint. Susan Andrews’ work is composed of 3 internal triangulations, the possibility of perfect geometry never realised, in a delightful unbalance of colour and elements. Andrews’ work often uses asymmetries as systems to relate to, and translate, other spaces and geometries observed in paintings, sculpture and architecture.20For instance, Susan Andrews’ subsequent solo exhibition Cutting across the field, at Five Walls Projects references Ralph Balson and Jean Prouvé. http://fivewalls.com.au/archives/4367 Over at Five Walls Projects, Rox de Luca collected and strung up a sinister contemporary fetish: dangling strings of discarded and weathered plastics collected from Sydney beaches, strangely lovely once sorted from detritus to order by colour, form and size, but nevertheless a sombre physical reminder of the volume of plastic waste our culture expels.

The balm offered by exhibitions such as Abstraction Twenty Eighteen to the continuing gender and currency biases of The Field and its successor, has been the way in which they highlight a close community of artists working inclusively in the field of abstraction.21Billy Gruner notes the presence and longevity of a community of reductive artists enriching the field by running specialised projects and spaces. Billy Gruner & Kyle Jenkins, NONOBJECT – New Work New Language New Modern.22This is not merely a local or a hierarchical phenomenon, but as Gruner describes it, a flat platform within a growing international arena. Billy Gruner, Gender Neutrality in Reductive Art, 2.23In Kiev, while The Field Revisited was on, in a full circle of influence over historicism, Gruner curated Icons \ W13, an exhibition homage to Malevich with 13 women artists from diverse countries. Icons \ W13, Kiev Non-Objective at Bulgakov Museum, Kiev, 22 May – 20 Jun 2018 curated by Dr Billy Gruner Almost a month after the opening of The Field Revisited, the NGV issued a belated statement, that ‘a notable omission from The Field was women artists’ and staged an ‘addendum’ exhibition showing their ‘recently acquired colour field and abstract works by Australian female artists.’24Hard Edge and Colour Field in the Collection – Women and The Field, NGV Australia, 28 Jun – 2018 While the NGV may have been attempting to make belated amends for its lack of inclusivity, the damaged and deteriorating condition of Wendy Paramor’s paintings, seen at a retrospective in Sydney in 2000 stands as a poignant metaphor for decades of neglect of women artists and their work.

Two of the three women artists of The Field returned to take part in the opening weekend of The Field Revisited. Janet Dawson and Normana Wight both gave public talks in the gallery (sadly, the third, Wendy Paramor died in 1973 at the age of 36). To stand before each of their works recently was to experience a moment of bittersweet art historical reflection upon the experiences of women artists. Visiting The Field Revisited is best done by travelling up via the escalators: this affords a spectacular moving view of the deeply joyous automotive-yellow of Wendy Paramor’s two-part modular sculpture: Luke, 1967. Of a scale massive enough to dominate the human, its enormity is balanced by the stately repose of its gently inclined curves and notches, the dual forms evoking the action of an enfolding embrace. Paramor’s second sculptural work, Triad, of 1967 rests on the floor nearby in a harmony of three undulating wave forms of white, underscored by black, the heavy steel somehow managing to mimic soft fabric. Working through the modulations of grey as a scale, Normana Wight’s vertically oriented painting, Untitled, 1968, remade 2017, is an elongated flared form containing its mirror-pair within itself. At 3.6 metres, its height is an imposing presence.

Yellow as a colour seems to have defined the 1968 moment: and Janet Dawson’s painting Rollascape 2, 1968 echoes the bright yellow hue – and unbridled joy – of Luke. Painted with rollers on composition board, its compressed sausage-like form manages to suggest contraction and expansion at the same time, on a resolutely flat surface. Of making it, Dawson says that to her it represented a joyous feeling of a landscape wanting to get out of the square frame …adding and also, I was a keen roller skater.25Janet Dawson, Artists on the Field public talk and discussion, NGV Australia, 29 Apr 2018 Dawson’s other painting, Wall II, 1968-9, could be read as a monochromatic study in flat geometries; but the title, and Dawson herself, reveal the influence to be Sydney’s high-rise construction boom of that time. Post-Field, Dawson turned to figuration, winning the Archibald Prize in 1973.

With Paramor’s death only 7 years after The Field, her moment has become frozen in time. Consequently, she is more often referenced as consummate Modernist, but there is a context to her initial success (which is) her later, effective erasure.26Joanna Mendelssohn ‘Paramor: Lost and Found’ in Artlink Magazine Her later works, which were figurative and expressive, are rarely mentioned. Curator Cecily Briggs described the state of neglect of much of her works when they were displayed in a retrospective in 2000:

Many of the works on view are in a shocking condition. Their state of disrepair reinforces the argument that the exhibition is but a part of the recovery of a lost reputation. Those who wish to see their art always perfect will wince at the scratches, flakes and dents in the canvases, the faded paper of the drawings. But there is no sense in just showing an airbrushed vision of art history. When reputations go, the physical works of the artist also fall into disregard.27Wendy Paramor: Lost and Found exhibition at Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre, Sep-Oct 2000

Yet physical works may be lost, then remade, or neglected, then conserved (as perhaps can a reputation).28Paramor’s sculpture Luke was remade in 2000 (in aluminium – the lost original was galvanized iron) whereas Triad was able to be conserved in 2000, both commissions by the writer/curator of the Paramor retrospective, Cecily Briggs.: Janet Dawson with Jenny Bell, ‘The Field? Yes! It was splendid!’ The Field Revisited Exhibition Catalogue, 121. After The Field had closed, and a subsequent placement of her work in the foyer of a project home had ended, Normana Wight had her large shaped painting returned to her; unable either to sell it, or to afford storage, she destroyed it by cutting it into small pieces (I want to imagine small geometric shapes) and burning it at a local incinerator.29Normana Wright, Revisiting the Field public talk and discussion, NGV Australia, 28 Apr 2018 She remade the work in 2017 for The Field Revisited. The Institutional acquisitions of Wendy Paramor’s30Wendy Paramor, Diablo, (1968-9), acrylic on composition board, 122.5 x 186 cm, Collection of Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre Sydney (purchased 2000) and Janet Dawson’s31Janet Dawson, Rollascape 2, (1968), acrylic on composition board, 150 x 275 cm irreg., Collection of Art Gallery of Ballarat, Ballarat (purchased 1988) & Wall II, (1968-9), acrylic on canvas, 184.3 x 184.4 cm, collection of National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (purchased 1969) paintings from The Field were integral to their survival, and their subsequent display in The Field Revisited.

One of its artists claimed that The Field was the only exhibition that ever opened a gallery and closed an art movement.32Alan Oldfield in Katrina Noorbergen, ‘Profile: Col Jordan’ in Artist Profile, Issue 42, 2018 Well, while the movement may be closed, and the moment passed, The Field Revisited, which at first reading might be taken for a silver-wrapped fable from the past, is really a ghost story. Fifty years on, in 2018 the Ian Potter Centre at the NGV was a haunted house, the spectral shapes of the excluded and the overlooked flitting unseen on its walls. In the years after The Field, one of its (female) artists recalled being accused of ‘betraying abstraction’. Exiting the dinner party for fresh air and a glittering city view (of Sydney, I believe), she recalled the moment:

‘What is abstraction? It’s not a person, or a thing, or a country, or a friend that can be betrayed; but an idea, a way of painting. I can paint whatever the hell I like.33Janet Dawson, Artists on the Field public talk and discussion, NGV Australia, 29 Apr 2018

Lisa Sharp

3 October 2018

References

Abstraction: Celebrating Australian women abstract artists. Exhibition Catalogue. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia Design and Publishing, 2017 https://nga.gov.au/abstraction/pdf/abstractionbooklet_online.pdf (28 May 2018)

Andrews, Susan, Cutting across the field, Exhibition statement. Five Walls Projects, Melbourne, 2018 http://fivewalls.com.au/susan-andrews-cutting-across-the-field/

Bergman, Amarie, artist website https://www.amariebergman.com

Butler, Rex and Donaldson, A.D.S., The Field at 50. Sydney: pushpress, 2018

Clement, Tracey, Field Notes in Tackling the Field

Dawson, Janet with Bell, Jenny ‘The Field? Yes! It was splendid!’, in The Field Revisited: Exhibition Catalogue, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2018, 121.

Reynolds-Kaye, Jennifer, Small-Great Objects: Anni and Josef Albers in the Americas. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017

Ellwood, Tony, ‘Field of Vision’ in The Field Revisited: Exhibition Catalogue, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2018, 50 – 59.

Gruner, Billy & Jenkins, Kyle, ‘NONOBJECT – New Work New Language New Modern’ in ICONS \ NONOBJECT in KNO Kyviv Non Objective (2018) http://www.kno.org.ua/site/kievnonobjective/home/kno-lab (28 May 2018)

Gruner, Billy, ‘Gender Neutrality in Reductive Art’ in ICONS \ W13 in KNO Kyviv Non Objective (2018) http://www.kno.org.ua/site/kievnonobjective/home/publications/gender (28 May 2018)

Hard Edge and Colour Field in the Collection – Women and The Field. NGV Australia, 28 Jun -2018

Leslie, Andrew and Lewis, Ruark, ‘SNO 106: Returning to the Field’ in SNO Contemporary Art Projects (2014) http://www.sno.org.au/sno106/ (28 May 2018)

Johnson, Anna, ‘Michael Johnson’ in Artist Profile (27 May 2018) http://www.artistprofile.com.au/michael-johnson/ (10 July 2018)

McDonald, John, ‘The Field Revisited’ in Sydney Morning Herald Review (25 May 2018) http://johnmcdonald.net.au/2018/the-field-revisited/ (25 July 2018)

Mackay, Kate, artist website, http://kate-mackay.blogspot.com/

Mendelssohn, Joanna, ‘Paramor: Lost and Found’ in Artlink Magazine (Dec 2000) https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/2489/paramor-lost-and-found/ (28 May 2018)

Noorbergen, Katrina, ‘Profile: Col Jordan’ in Artist Profile, Issue 42, 2018, 102-106

Nordrum, Charles and Kate, ‘Ron Robertson-Swann: Radiant Colour, Clarity and Crisp Light in Embraced Space’, Exhibition Essay, August 2018, Charles Nodrum Gallery, Melbourne, https://www.charlesnodrumgallery.com.au/exhibitions/ron-robertson-swann-radiant-colour-clarity-and-crisp-light-in-embraced-space/

Oldfield, Alan, ‘Remembering Wendy’ in Paramor: Lost and Found, Exhibition Catalogue, Casula Powehouse Arts Centre, 2000, 38 – 50.

Rozentals, Beckett, ‘The legacy of The Field’ in The Field Revisited: Exhibition Catalogue, Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2018, 14 – 37.

Sarroff, Marlene, artist website http://marlenesarroff.com/

Sigglekow, Zara, ‘The Field Revisited: A guide to its unofficial satellite exhibitions’ Feature in Art Guide Australia (3 May 2018) https://artguide.com.au/the-field-revisited-a-guide-to-its-unofficial-satellite-exhibitions

The Field. Exhibition Catalogue. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1968

The Field Revisited. Exhibition Catalogue. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 2018

Thomas, Natalie, ‘Finding the Field’ in Nattysolo.com (2018) https://nattysolo.com/2018/04/11/finding-the-field/

Wickham, Stephen, ‘Abstraction Amplified’ in Abstraction Twenty Eighteen: Exhibition Pamphlet, 2018, Melbourne.

Winata, Amelia, ‘Finding the Field, Natalie Thomas and The Women’s Art Register at True Estate Gallery’ in memoreview (2018) https://memoreview.net/blog/finding-the-field-by-amelia-winata

Wolff, Sharne, ‘Revisiting The Field’. Art Guide Australia (20 December 2017) in https://artguide.com.au/art-plus/revisiting-the-field (28 May 2018)