Sam Cornish: Five questions for Phillip King and Tim Scott

Phillip King

In retrospect, what do you see as the central achievement of the so-called New Generation sculpture of the 1960s?

In the Primary Structure show put on by Kynaston McShine, some British sculptors were included and that work has been described as ‘Lyrical Abstraction’, as opposed to the austere American abstraction of Judd, Andre and Morris. Sculpture had been in a post-war mode and described as ‘Wounded Art’. Colour (an expansive approach, placing the work on the same level as the viewer), primary form – easily grasped and an optimistic approach to life – these are the hallmarks of the new work of the 1960s.

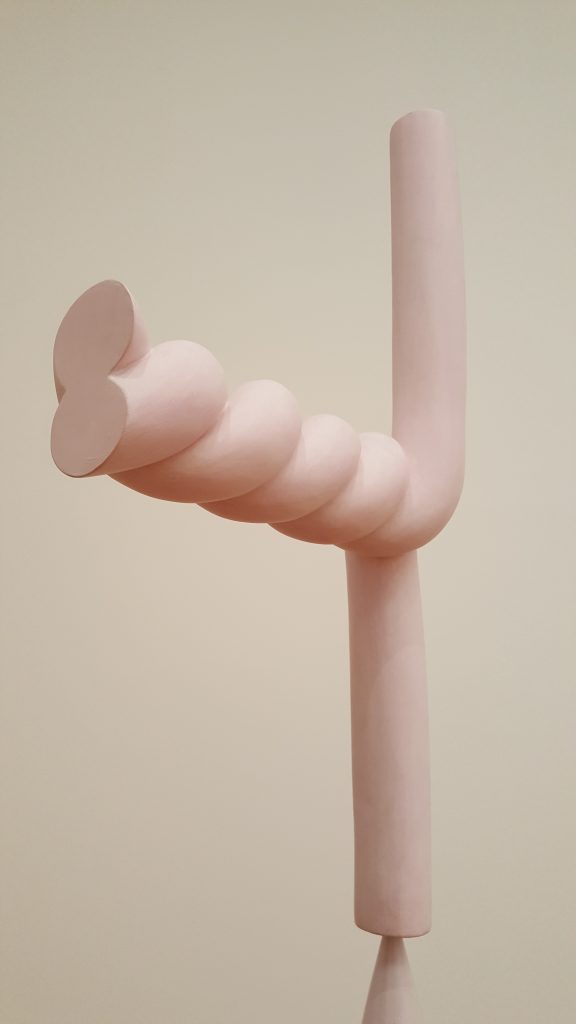

What are your feelings about ‘Tra-La-La’, now on display at Tate Britain?

I haven’t seen ‘Tra-La-La’ yet. Last time I saw it was in the Tate Stores and it needed some attention and some invisible changes which I suggested; the top element had completely faded. Hope they fixed it all.

How much do you see your current work as continuing or rejecting the ideas of the sculpture of the 1960s?

The wheel goes round and round and one can revisit early work but it can never be the same. I have all my work in constant review, and attitudes can change; but I regret none of it.

There is general agreement on the art that formed the background to the British sculpture of the 1960s. The expansive scale of mid-century American painting, the volumes of Brancusi, Matisse’s cut-outs, David Smith’s constructed steel sculpture. Is there an artist not normally considered within these influences, who was particularly important to you in the 1960s? Whether or not you are conscious that their example made itself felt within your own sculpture.

In my case, and also shared with Bill Tucker, the Russian Constructivists: Tatlin, Malevich and Meduniezky. Matisse (the figures), Rodin (the late work), Degas, much so-called primitive art (American, African, Oceanic, Buddhist, Khmer, etc.) and, for me, Picasso, Laurens, Schwitters, Vantongerloo, Noguchi, Max Bill and Katarzyna Kobro. I am always discovering something new to admire and perhaps be influenced by. I consider all that I like in art as part of me, and it has grown bigger over the years.

How do you feel about the present (and future) of sculpture?

Who knows, I would already be there if I knew. New materials and technology make for changes in art: from gas welding to arc welding – read Gonzales and David Smith. I certainly find that polyurethane foams have allowed me to move in a new direction. The new may be around already, but unrecognised. It won’t be necessarily due to celebrity and money.

Tim Scott

In retrospect, what do you see as the central achievement of the so-called New Generation sculpture of the 1960s?

The break with the angst ridden figuration of the fifties, which formed the basis of my student years. Breaking with tradition is one thing of course; replacing it is another.

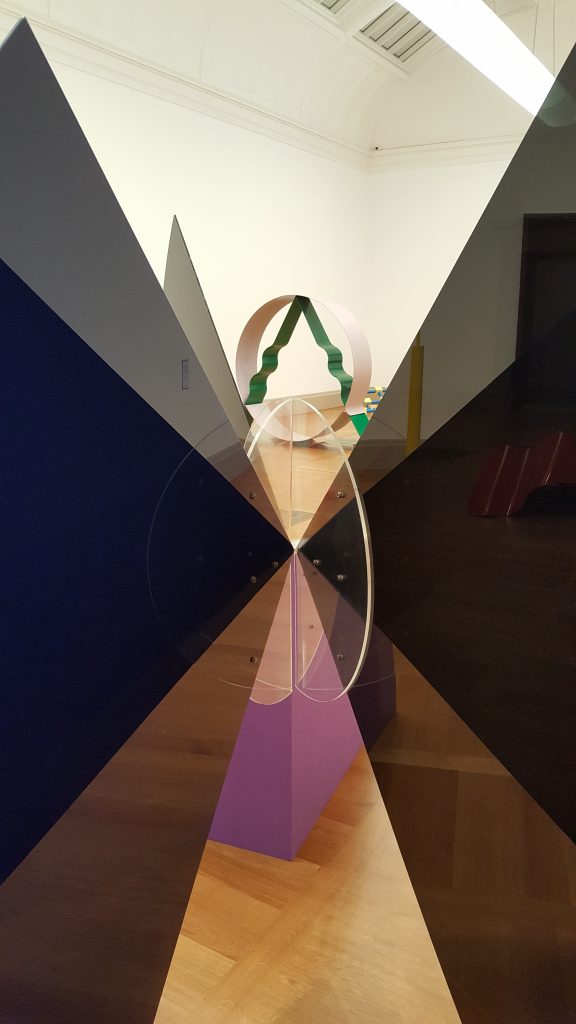

What are your feelings about ‘Quinquereme’, now on display at Tate Britain?

‘Quinquereme’ is not, of course, what I would do now. However, I do sometimes regret the boldness of its expansion and occupation of space, and the ground it occupies.

How much do you see your current work as continuing or rejecting the ideas of the sculpture of the 1960s?

Observers have often remarked to me that they see similarities in one aspect of my work to another; despite the fact that I was not aware of it myself. So I suppose that an artist always has some sort of ‘signature’ which is a continuum.

There is general agreement on the art that formed the background to the British sculpture of the 1960s. The expansive scale of mid-century American painting, the volumes of Brancusi, Matisse’s cut-outs, David Smith’s constructed steel sculpture. Is there an artist not normally considered within these influences, who was particularly important to you in the 1960s? Whether or not you are conscious that their example made itself felt within your own sculpture.

Poussin’s clarity.

How do you feel about the present (and future) of sculpture?

Caro’s “Onward of Sculpture” is a battle cry with which I firmly agree. It is deplorable that

a noble art form should be submerged and trivialised by neglect and lack of effort.

One thought on “Sam Cornish: Five questions for Phillip King and Tim Scott”

Comments are closed.

What a great answer – “Poussin’s clarity”!