Emyr Williams: From the Paint Face, No.1

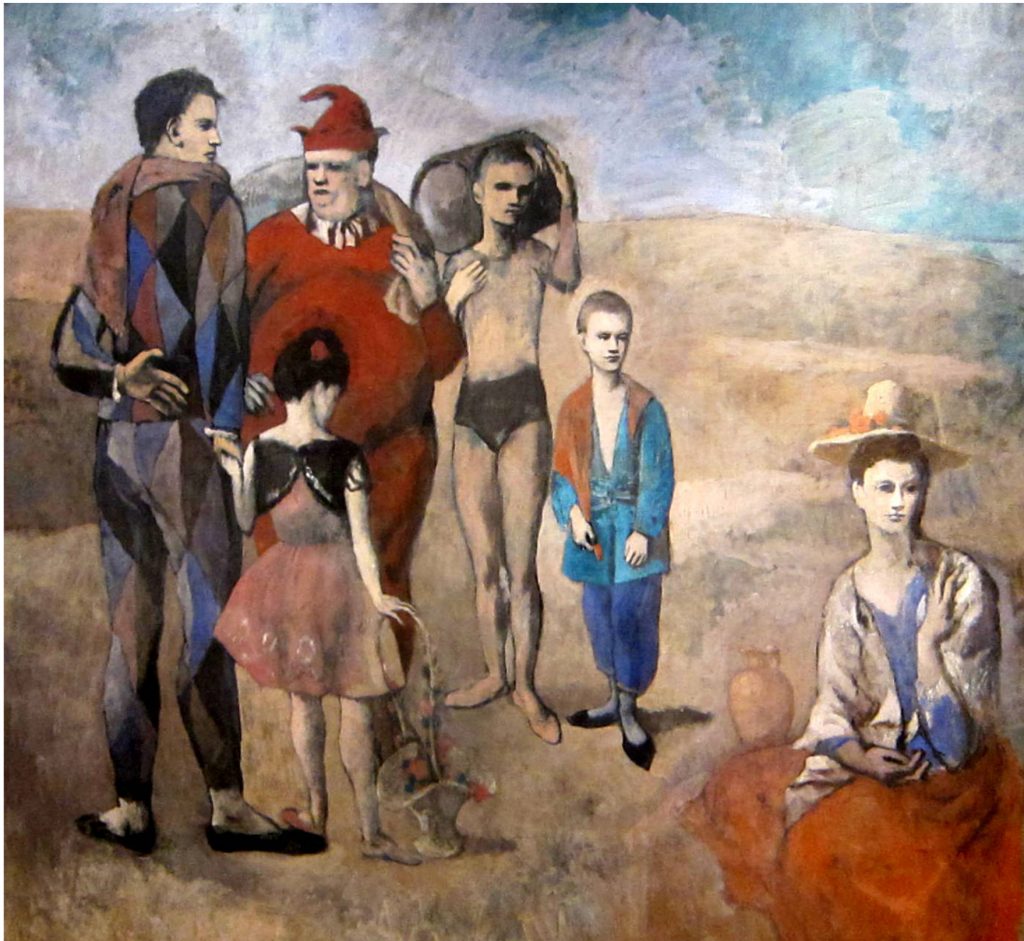

Pablo Picasso, ‘Family of Saltimbanques’ (‘La Famille des Saltimbanques’) (1905), oil on canvas, 212.8 x 229.6cm

Picasso, whilst living in the Bateau-Lavoir (has there ever been another such mythologically romantic place in all of art history?) would often visit the Cirque-Medrano – a popular circus located in the area that would also house the Moulin Rouge and the Moulin de la Galette- and the characters he witnessed there informed the subject-matter for many of his post-Blue Period Rose paintings. The large Les Saltimbanques (1905), at 7ft x 8ft, has held my attention as a painting for many years, and in fact is an early major work that intrigues me more than the notorious Demoiselles D’Avignon painted two years later. Ironically, unlike the incendiary Demoiselles, in the Saltimbanques the paint itself is doing the majority of the work; the painting looks very comfortable in its own skin. There’s the interesting storyline about who is who in the work: Apollinaire being the tubby jester, Andre Salmon or Max Jacob the tall acrobat, and Picasso’s lover Fernande Olivier the female figure on the periphery.

The composition can be traced via Manet, to the spareness in a great Goya, and further back to Roman and Greek figures – witness the pose of Fernande (even with a dislocated articulation of fingers). The figures themselves conjure up comparisons with Giotto in their deployment of facial shadows used for structuring the cranium. In fact, the whole work is dripping with an historical classicism that reveals Picasso’s artistic DNA. His connection with the classical underpinned all areas of his work until his death. Picasso is a covert colourist, and this work demonstrates just how in control he could be with his colour; the earths which just keep going are future indicators of those late easel work pyrotechnics, which have a similar painting out of space rather than a filling in of it. Unlike Matisse, who championed the importance of colour in building space and creating luminosity, Picasso would brag about running out of blue and using red instead – colour was just a filler, so to speak. Yet I don’t buy this bravado; Picasso is letting the colour do the work of building the space of the desolate hinterland that these characters have settled in. The brushstrokes swing about and weave oiled-out earths and chalky blues. Each of the characters has clothing the colours of which come out of this ground space, with its tempered hues reclaimed by the landscape; their presence is immutable, statue-like and heroic in disposition, as a stark counterpoint to the animated busyness of the colour space surrounding them.

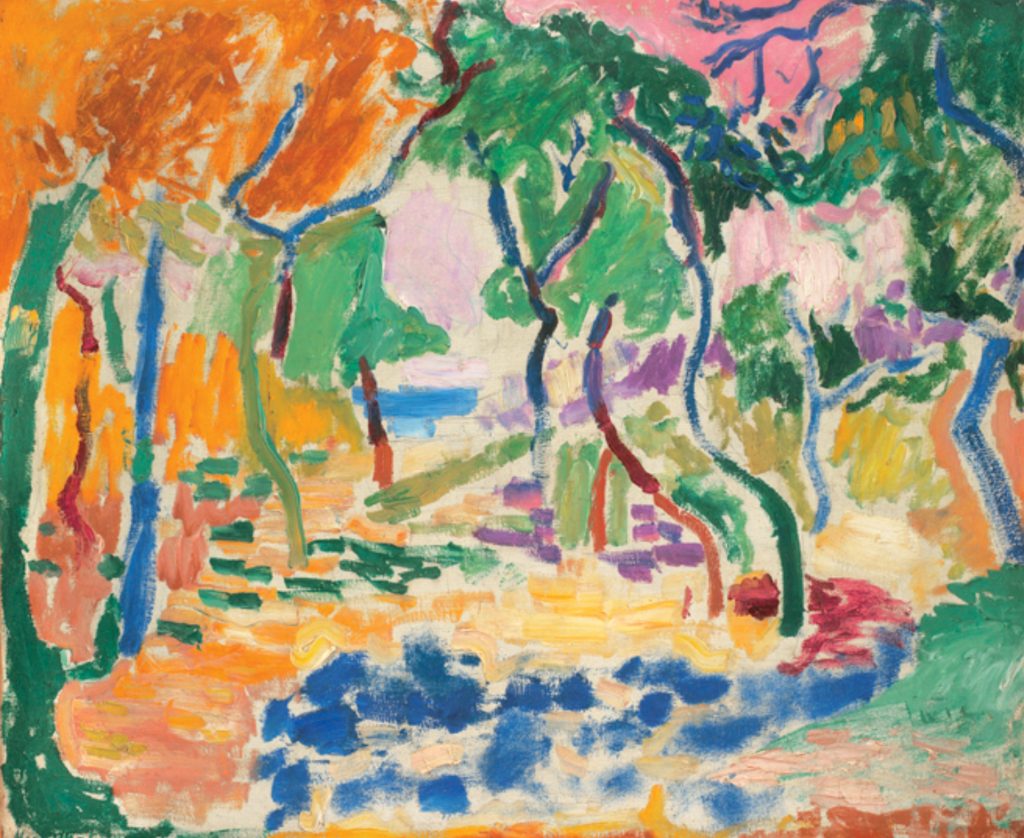

Henri Matisse, ‘Landscape near Collioure: Study for ‘The Joy of Life” (‘Le Bonheur de Vivre’) (1905), oil on canvas, 53.4 x 45.7cm

During the same year that Picasso was mooching about Montmartre, Matisse was down in Collioure, towards the Spanish border, painting some of his greatest – soon to be known as – Fauvist works. His Landscape at Collioure (1905), a study for the seminal Bonheur de Vivre, is a work that I have prized all my adult life – so much so that in my twenties I made a special journey to Copenhagen to see it. Matisse used to joke that Fauvism was when it had red in it; yet this work is a symphony in predominantly secondary colours – the reds are mere accents to the magical invention of brushed colour and rhythmic linear elements (again, always reading as colour). This is a work that ‘destroyed’ painting in much more brutal ways than Miró ever wilfully managed – by not trying too hard to ‘look like art’. As if in a moment of prescience that illuminates his connection with the emphatic frontality of Russian Icon painting that he went on to explore in subsequent years, the paint in this work stings against the canvas, drum-like in its tension; that sudden chilling of mountain stream water to the throat as one drinks on a hot day – the colour here startles and shocks in its clarity. The surface has an emphatic ‘slap-panel’ quality to it, and although the space is palpable as landscape, it refuses to yield to the conventions of foreground and background – the colour has an aerated quality and the familiar perfume of pine trees pervades (if you have experienced that). It is so ‘real’ as a landscape due to the unique catalysing of its synthesis, yet it lives in the shadows of the great Bonheur, which of course has figures in it, and, as such, an immediate connection with historical subject matter. Picasso seems the better for these links whereas Matisse (ironically, the inveterate bourgeois) is at his best when the shackles of Europe are slewed off. Picasso is a draughtsman who excelled at line and tone – two elements that are symbiotically connected to form and figuration; whereas Matisse, the man of hue, has become a gatekeeper for abstract art.