The Tension Between: Stephen Buckeridge on the Paintings of Clare Price and James Hayward

‘Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time present contained within time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

What might have been is an abstraction

Remaining a perpetual possibility

Only in a world of speculation.’

T.S. Eliot, Burnt Norton, from The Four Quartets

Eliot’s poem starts with the line ‘Time present and time past’, which suggests something unformed, between states, and unknown, something that could exist in both the present and the past, something that exists but doesn’t exist in a physical sense. The contrast between time past and present creates a tension between the two adjectives. Adorno writes about the tension between the element, frame and surface, where the beauty is not simply the equilibrium per se – but rather the tension between those states that results in a kind of stasis or a point of becoming. The painting ‘Untitled 2015’ by Clare Price is a work that I have repeatedly returned to: it is a painting that I own, and one that sits with a number of other works from differing oeuvres. It is a painting that doesn’t sit comfortably; it jars and jostles and keeps pricking at one’s consciousness, reminding oneself of its existence.

The painting is made with oil and acrylic on canvas, and at 40cm by 30cm is quite small in relation to her larger paintings; and yet it suggests a kind of monumentality that extends beyond its frame. The painting is constructed from a small number of elements: the surface is stained with inky blues and blacks, which vary in their opacity and saturation; there is a pink diagonal stripe that moves from bottom left to top right, and a cluster of gestures which appear from the bottom left toward the middle of the painting along the same diagonal. The colour palette is one of pastel pinks and blues, quite soft and subtle; and muted greys and inky blacks, which vary in intensity from the opaque to the bled out. The diagonal division enables the eye to move across the surface from bottom left to top right, thereby suggesting that the composition continues beyond the edge of the frame. At first look, one sees a surface that appears spontaneously formed: a blotted, soaked surface where the materials have been allowed to find their natural edge. Some elements appear opaque, others solid: and all are dissipated across the surface as if fired out from an aperture at cosmic speeds. The painting’s matter spreads across the surface in a completely haphazard, uncontrolled way, suggesting a kind of spasm or cataclysmic event: in particular, it evokes John Martin’s ‘The Great Day of his Wrath’ of 1851, where an apocalyptic vision closely follows the biblical account: ‘There was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood … And the heaven departed as a scroll … and every mountain and island were moved out of their places.’ The earth crashes in on itself, underlining the futility of mankind’s attempts to resist the will of God.

In Clare Price’s painting, some elements- such as the diagonal marks- appear to sit on top of the surface, whilst others appear to sink and submerge into the weave of the canvas, which is exposed in some places. The painting conveys a sense that one is looking at a fleeting moment – a moment, perhaps, that belongs to a grand event, something that could appear to exist in both the present time, and as a remnant of something from the past. Indeed, the chaotic atmosphere of the painting suggests the formation or the beginning of something – something biological, or more fundamental even: an astronomical or celestial event, a moment from prehistory. The order or structure of the painting is confined by the surface and by the existing frame – the edge of the painting, where the spillage has also found its natural edge. The tension between the surface and frame is evident: there is a sense that the frame has contained the spread of matter and that this act, in itself, intensifies the relationship or tension between the opaque, the poured and the stained elements on the surface.

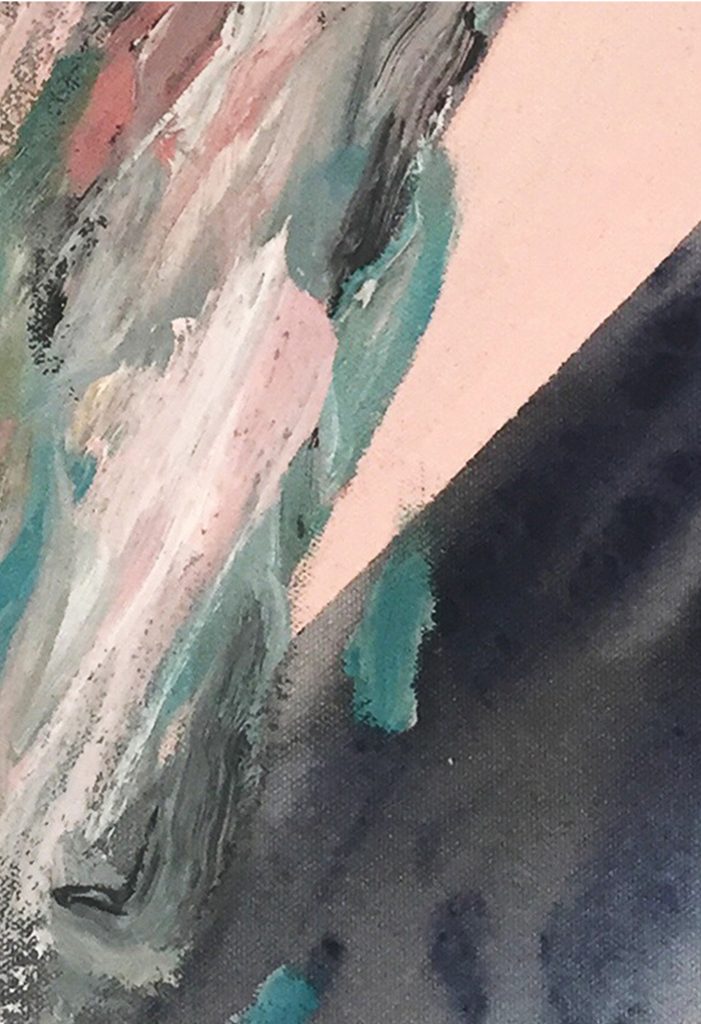

Of the painting’s two zones, divided along the diagonal, the top left zone contains deep space, populated by small fragments of matter, whilst the bottom right zone presents a shallower space: this latter space is, at the same time, more physical and dense, its stained black marks offering a view into an unknown and absorbent space that emits no light. The tension within the surface is further emphasised by the pale pink diagonal that appears to taper from the top right hand corner towards somewhere – behind? One can’t be sure! The end of the diagonal had been lost, obliterated by a dense weave of heavy smudged marks that have been dragged and smeared across the central section; some appear to be clustering towards the centre from the bottom left, as if the marks are attracted towards the clear sharp edges of the diagonal, and are feeding on them. This slow absorption of the pink form by the gestural marks erodes the masking-taped edge of the diagonal, and the resultant sense of organic process working on the mechanical further heightens the tension between the two elements.

In the John Martin painting, the two large rocks are about to tip into the void that opens below them, and the small opening below the right hand rock accentuates the tipping point, the moment when gravity finally pulls them into the abyss: and this tipping point from one state to another finds several echoes in Clare Price’s painting, for instance in this detail:

One becomes aware of a kind of osmosis, a transformation, where the surface is beginning to evolve, moving between different states– in this case, two contradictory ones, the absorbent and the impermeable. It feels almost too obvious to state that we are witnessing a kind of micro/macro tension, where there is something that is about to happen or is happening to disrupt the calm. Even within the subtle background, with its surface of soft muted stains which appear to bleed into one another, a tension is created by the way in which they are absorbed into the surface. The coloured pink and blue marks at first glance look pure; yet, upon closer inspection there is something tainted, something unclean and impure about the blue, as if contaminated by the oily grey and black marks, whose contrast with the surface serves to increase the sense of deep space, and which are clearly sitting in front of the pink diagonal.

These marks also suggest a way into the surface. Writing about Clare Price’s paintings, James Finch suggests that ‘What unsettles is that these techniques are all estranged, refugees from their home territory. We are looking at something or we are looking into something’1James Finch (2014) ‘I killed a Viper – Clare Price’ https://abstractcritical.com/article/i-killed-a-viper-clare-price/index. (14th June 2014). The dragged and smeared marks sit on the surface, and yet appear to float high above the soft stained ground: we are clearly looking at something, and yet the relationship between marks and ground also suggests that we are looking into something. The discordance between the three components- smears, stains, and surface- is felt not only in their innate differences, but also in the way they clearly define different spaces. At the same time, however, the heightened contrasts between gestural marks and the surface to which they are applied generate a tension which, paradoxically, serves to yoke the elements of the painting together, imbuing it with a sense of stability.

Clare Price’s painting puts one in mind of the work of James Hayward: it is their shared concern with the fluctuation between stable and unstable states, I believe, that links Price’s and Hayward’s work. In his essay ‘Nonrepresentation which doesn’t Represent’2 Gilbert-Rolfe, J. (1995), ‘James Hayward, Nonrepresentation that doesn’t represent’ in Beyond Piety: Critical essays on the visual arts 1986-1993, New York, University of Cambridge, pp96-98. Jeremy Gilbert–Rolfe characterises Hayward’s work as follows: in a painting such as ‘Abstract Diptych #45’ of 2017, illustrated here, ‘the surface is that which underscores the physicality of the painting, the colour that which robs things of their stability as things and turns them instead into spaces which aren’t there.’ Gilbert–Rolfe goes further, drawing on the example of Monet’s paintings of Rouen Cathedral, in which ‘it seems as though space, which is intangible, is somehow linked with tangibility, the surface as a crust or layering.’3Gilbert-Rolfe, J. (1995), ‘James Hayward, Nonrepresentation that doesn’t represent’ in Beyond Piety: Critical essays on the visual arts 1986-1993, New York, University of Cambridge, pp96-98. Thus, Hayward’s painting, which doesn’t allow us to see beyond its crust (lacking the deep illusionistic space of Price’s painting),does, however, remind us of the physicality of the space that we inhabit. If we experience Hayward’s painting as crust, it thereby articulates what it is not, namely, that it is not a space; by the same token, Price’s painting is certainly concerned with looking into a space, yet at the same time it demands we consider whether we are looking into something or whether we are looking at it.

Hayward’s painting is a diptych – with both halves similar in their mark-making and layering of the surface, which remains dense and unremitting. Light is absorbed and to some degree the surface resists and rejects illusionistic space. The blue and dark orange appear to be emanating from the raw sienna, and conversely, the raw sienna slowly envelops the lightness and vibrancies of the blue. On the right-hand panel- the more absorbent and physical of the two- the tone of the colour is more uniform, and appears to be a mix of the two other complementary colours. The blue and orange on the left hand panel suggest a kind of light that sits on the surface, slowly being absorbed into the morass of dragged marks. The evidence of the hand is found in the array of brush marks which crisscross the surface, each gesture adding to its density, pulling and pushing it, which in itself offers a tension between each mark and the surface as whole. Each mark appears fresh and removes the trace of what existed before; the memory of the marks has been erased by the repetitive overlapping of the gestures. One would assume that the nature of the mark would offer some kind of residual memory of its making, but this is not the case: it is unclear what has made it, whether brush, knife, or spatula, and the repetitive nature of each mark also suggests a process that feels machine-like. Tensions across the painting’s surface are enhanced by the dual character of the marks- organic, yet uniform- and they form a palimpsest that reveals nothing of its origins, allowing only the sense that it has been reworked, over and over.

Julie Mehretu, in her notes on painting, writes that ‘marks are percussive, repetitive motions, marks that shift with each motion, faster accelerating to gain that wicked mass of marks – a being that devours, consumes, digests and decimates their place until they morph/shift it/fuse into it/splice through. To find the break in the linear – the mark is insistent.’4 Mehretu, J. (2014) ‘Notes on Painting’ in Gra, I. and Lajer-Burcharth, E. (eds.) ‘Painting beyond itself – The Medium in the Post-medium Condition’, New York, Sternberg Press, pp 271-276 In both Hayward’s and Price’s work there is insistency and a tension between marks, and between the surface and its edge. In Hayward’s painting, what strikes us is how the small detail is a microcosm of the whole – the surface appears gooey, almost alive, a visceral layer that projects itself beyond its support. In this painting there exists a different tension to that evoked by Price’s work, with its focus upon some kind of event; rather, in Hayward’s surfaces we seem to be in the presence of a biological culture, of bacteria multiplying, or a scientific experiment; even, perhaps, a kind of merging of different species within a homogenised surface. Nevertheless, common to both is the way in which marks or matter appear to be on, as well as in, the painting surface.

In sections of Price’s painting the surface materiality appears to be in a kind of conflict with itself. The evidence of the hand – the smeared gesture- vies with the sharp, mechanical pink diagonal, and hthe soft bleeding of the surface. The smeared marks offer evidence of the body, not remote but active – distilled from the diagonal and the muted, bled background. Between them, these three elements provide a transitional space: a potential space where there is overlapping between things neither subject nor object, things not settled by clear boundaries. This reading can be applied to the material, the gesture, the surface, the support and its edge. In both Price’s and Hayward’s paintings the tension is not merely confined to one area, but operates across the whole, between surface, matter and structure. The multiplicity of discordant qualities lend life to the paintings, and provide a constant target for scrutiny. It is this tension between that draws one into the space and holds our attention: one is reminded of interstellar photography, or biological metamorphosis viewed through the microscope.

David Winnacott suggests that beauty can be seen to be in conflict, or in a state of contradiction with itself: once again, a kind of tension. The gaps between perceived boundaries within both of the paintings under consideration offer a space for language to operate. In their differing ways, both paintings inhabit a space between environments, between states, being neither one nor the other. It is the questioning of these boundaries, and the incongruity of the resultant discordance that gives rise to tension: this tension is situated somewhere between the terms past and present, and thus enables me to return to the point where I began:

‘Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time present contained within time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

What might have been is an abstraction

Remaining a perpetual possibility

Only in a world of speculation.’