Too Late for Late Modernism: Selma Parlour in conversation with John Bunker

JB: When Michael Stubbs and I came to hang your piece for the group show ‘Destroyed By Shadows’ at Liverpool Hope University earlier this year we knew we wanted to foreground how the work might interact with the architecture of the gallery. There are moments in the day when some great shadows are cast from the large window near the work. After spending a bit of time with your piece I really began to see the intense colour play in your work- and how it interacted with the changing natural light. Perhaps you could talk a little about how you approach colour? And how it works in relation to your seemingly meticulous surfaces.

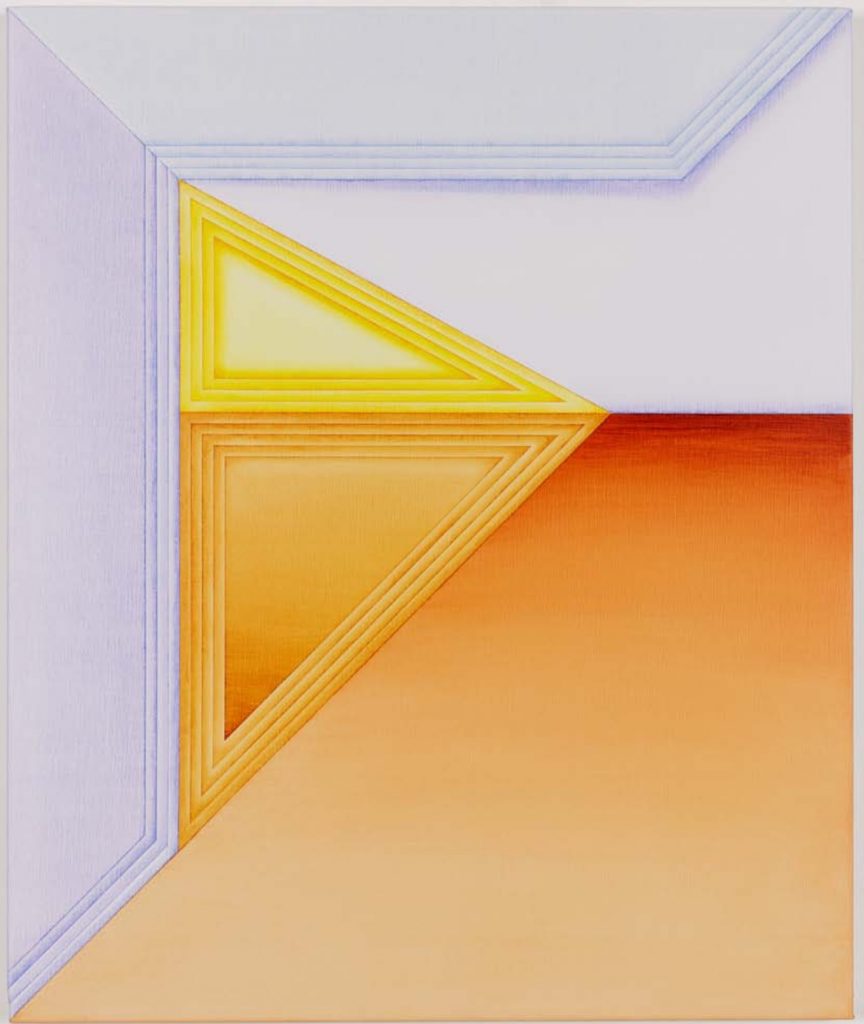

SP: Colour is so difficult to pin down; it is intuitively derived, sometimes local or reminiscent, but mostly each choice dictates the next. I work with transparent films of oil paint on linen in such a way that the warmth of the material surface is inseparable from colour. In ‘Flank I’, image/colour/surface is one thing for me. I wanted the lime to dissolve into ‘space’ and then reform as orange as the viewer’s gaze travels down the painting. The diagonal positioning of my shaded bands speak to cast light. Your curation adds to the transformation of painting into stained-glass window.

JB: “I work with transparent films of oil paint on linen in such a way that the warmth of the material surface is inseparable from colour.” That is such an interesting way of describing a process. It feels so close to a way of talking about colour and surface prevalent in late modernist works- the post-painterly abstractionists immediately come to mind- like Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland. Yet, would you say your ‘shaded bands’ and the luminosity you achieve so seamlessly across your surfaces, also talk about the intensities of the ubiquitous backlit screen?

SP: Yes, as my transparent colour is backlit by the white primer beneath, the paintings glow. The virtual screen is more than a trope for material invisibility; if Alberti’s drawn open window is a construct for creating an elsewhere, a screen reflects us. We are trapped within it. Sadly, I was born too late to be a late modernist. We all have to find our own way through the languages we’ve inherited. In contrast to the openness felt in paintings by the colour field painters, I think about containment (for what it does to fictive space). Painterliness is absent; my surfaces are very flat and look printed. I am barely there. The idea of painting by way of a virtual screen serves to emphasise this but the viewer’s sense of touch (in the warmth of surface) holds strong.

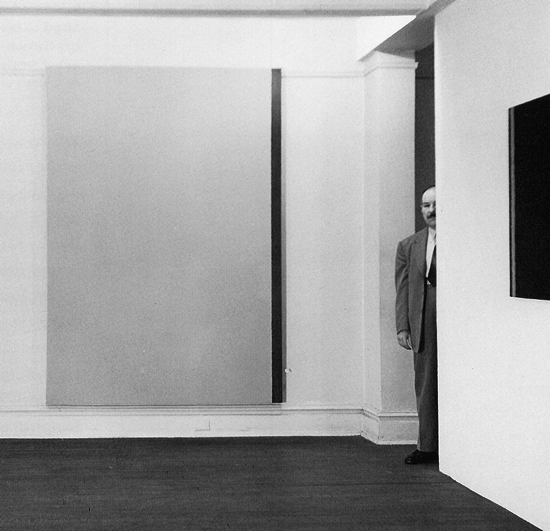

JB: This notion of a lost sense of ‘openness’ and a sense of ‘containment’ is intriguing. A series of photographic images from history come to mind- those of Barnett Newman in his exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery from the 1950s, and later more suggestive images of himself and an unidentified woman standing before his work. You could see the Betty Parsons exhibition as an attempt to completely enclose the viewer in a painterly gestalt- as a kind of forebear of installation art and expanded painting. There is this strong sense in Newman of foregrounding the physical interaction between the body of the viewer and the painting in relation to his famous ‘zips’. By suppressing painterly ‘action’ he, by turns, sort of intensifies his absence and thus intensifies our, the viewer’s, presence. Does this process relate in any way to your work? Could you talk a bit more about how you might use photographic sources in your work and how you might see painting in relation to site and architectural spaces?

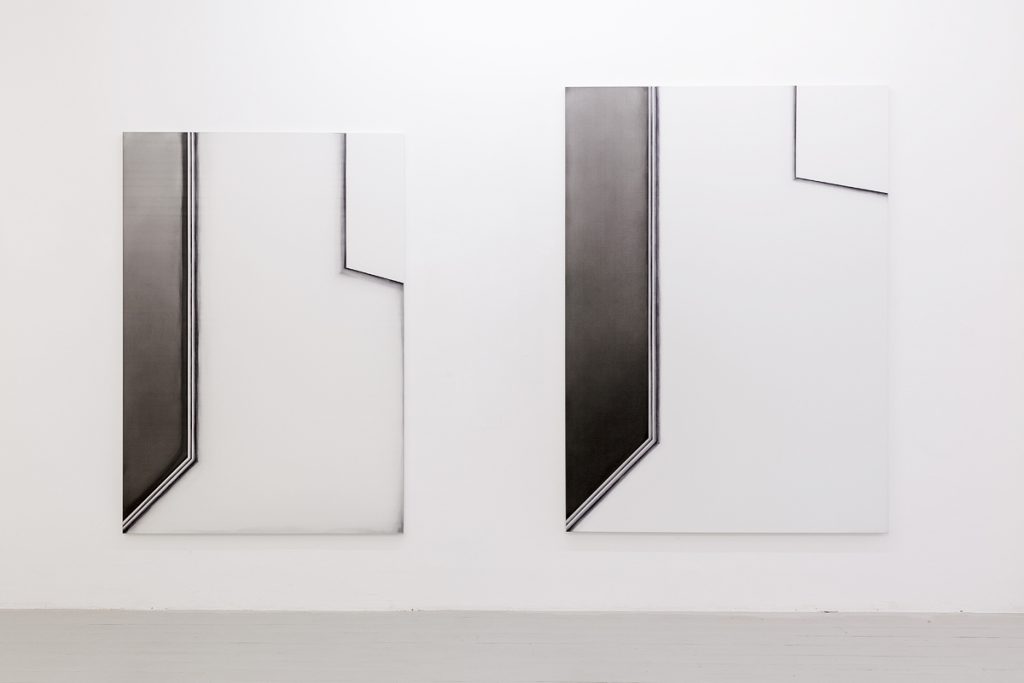

SP: Those photographs are great, especially the one where Newman is seemingly cut in half. To be both coy and severed! I agree, Newman’s zips absolutely intensify our presence; I think it’s in the reiteration of verticality and scale. Yve-Alain Bois has a beautiful text on how the zips alter our perceptual activity. In my ‘Upright Animal’ series, what appear to be drawn/shaded lines are actually expansive films of oil paint pushed to masked-off edges. I made them in relation to my body and the material limitations. The title is a throwaway term I’ve borrowed from Brian O’Doherty: “The wall itself has no intrinsic esthetic (sic); it is simply a necessity for an upright animal”. O’Doherty writes on the ideology of the gallery space. I also used this title for my recent show at Pi Artworks, London. For me, the repetition cues us to consider the fictive space in my films of paint in relation to the real place of display. But moreover, I’m so pleased that you’ve received that series by way of photography’s installation shot of Newman rather than intuiting a direct, or unprocessed, service to his paintings. We come back to containment. Photography’s installation shot of abstract painting contextualises (and flattens) the architecture of the gallery space alongside the work of art. It is a convention that has grown alongside abstraction (we don’t typically feel the need to include the space around representational works when documenting them). I’m not copying images of exhibitions as such. In my paintings, I am trying to create a mediatory space: neither abstract painting nor installation shot.

JB: I’m interested in what you mean by creating a ‘mediatory space’ in painting. Thinking about your ‘Upright Animal’ show, it seemed like there were correlations to be made between the spaces of the gallery and the fictive spaces generated by the colour, the paint application and the directional armatures or shaded bands in the paintings themselves. This commenting on the ‘act of looking’ at pictures seems particularly acute in the large black and white paintings. I’m wondering how you organise the spaces in the paintings. Do you work from preparatory drawings or computer generated images? Or is it more intuitive and/or physical? Following on from these questions, I think you have worked on a site-specific project recently? I liked what you said about the convention of photographic representations of abstract paintings having foregrounded the settings in which they hang. Do you recognise that tension between seeing a painting as a self contained entity and making paintings that exist solely or mostly by foregrounding their relationships with the site?

SP: I’m in the habit of roughly sketching, but this is really only to record my paint choices and method for future reference. I conceive of the paintings as diagrams and typically visualise them in my mind’s eye. But each painting leads to the next. A big part of my project involves an approach to painting through distinct and repeatable units. Some of my favourite artists do this: Mondrian, Johns, Stella, Mangold, Martin, Lasker. It always seems to bring with it a related sense of drawing. My spaces are organised to the structure of painting as both a flat and enclosed rectangular field and an imagined box space. The tension between real material surface and fictive shallow relief is brought to the fore through my shaded bands and by the perceptual shape-shifting possibilities of abstract imagery, for example, how a trapezium can look like a rectangle canting into illusionary depth. In 2016, I undertook a site-specific installation in the main dining room of the Grade 1 listed House of St Barnabas, London, making paintings to fit the 222cm tall Rocco panelling from the 1750s. Without the blankness a white cube gallery space affords, I was forced to respond to the colour, furniture and architecture of the room. The walls are a very matt beige that sucks in the light, but it served surprisingly well as a backdrop to my luminous colour. I took my cue from the entablatures, shutters, corners and recesses. In order to blur the boundaries between real and imagined, my shading complimented the silvering mirror and of the mouldings. So I’m not only looking to the contextual space of display for referents for my repeatable units, I’m activating a reciprocal visual relationship where spatial plays and recognition lie with the viewer.

Selma Parlour, Two Installation views of ‘Parlour Games’, Marcelle Joseph Projects, House of St Barnabas, London, (2016)

JB: I’d like to change tack for a moment and go back to what you said earlier concerning potential relationships with the history of art. I think you said “We all have to find our own way through the languages we’ve inherited.” Now that you have mentioned some historical figures, I’ve suddenly realised I’ve made several references to a very particular lineage in post war American art, one which pretty much paved the way for what was to become known as minimalism in the 60s. Also, the artists I’ve cited are all male! Are there female artists who have set an example for you- either workwise or in attitude- historical figures and/or very contemporary ones?

SP: Aside from Agnes Martin (who is the only woman I cited previously), Frankenthaler and O’Keeffe spring to mind. Amy Sillman, Chantal Joffe, Laura Owens, Katharina Grosse, Marlene Dumas… there are loads of amazing painters out there. Historical references that resonate with me include Duccio, Piero, Giotto, Seurat, Monet, Matisse, Picasso, and Newman and all those colour field painters and minimalists! I’ve just won a residency award from the Mark Rothko Memorial Trust, there’s something very special in activities that link us to the past. I’ve developed my art practice in tandem with research; picking my way through the contemporary currency or redundancy of past traits and effects necessitates and drives my practice.

Selma Parlour, Installation view (2017)

Selma Parlour, ‘Compile Time IV’ (2017), oil on linen, 150 x 160cm

Selma Parlour, ‘Compile Time III’ (2017), oil on linen, 150 x 160cm