‘Celebration’ at the Mercer Art Gallery, Harrogate

‘What is all this juice and all this joy?’1From the poem ‘Spring’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins

‘Celebration’ isn’t a word Instantloveland tends to hear being used all that often these days; at least, not in connection with abstract painting. Good Lord, no. In case any of you hadn’t yet noticed, in the painting culture of the twenty-first century, celebrating anything is very, very far from most people’s minds. ‘Interrogation’ is all that abstraction’s good for now, supposedly: the exhaustive probing of its claims to continuing legitimacy, and the more protracted and remorseless the process, the better. It’s a dirty job, but someone’s got to do it; and as Michael Sugrue2Harvard Professor of Philosophy, and author/presenter of the video lecture series ‘The Great Minds of the Western Intellectual Tradition’https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=the+great+minds+of+the+western+intellectual+tradition has pointed out, this fashionable term, used to the point of exhaustion in so much of the critical discourse around painting, has connotations that are very far from friendly: not so much the panel discussion with a Q & A afterwards, more the soundproofed basement room at 3am with the car battery and the jump leads. Don’t make it hard on yourself, abstraction: just spill the beans, and then we can all go home…

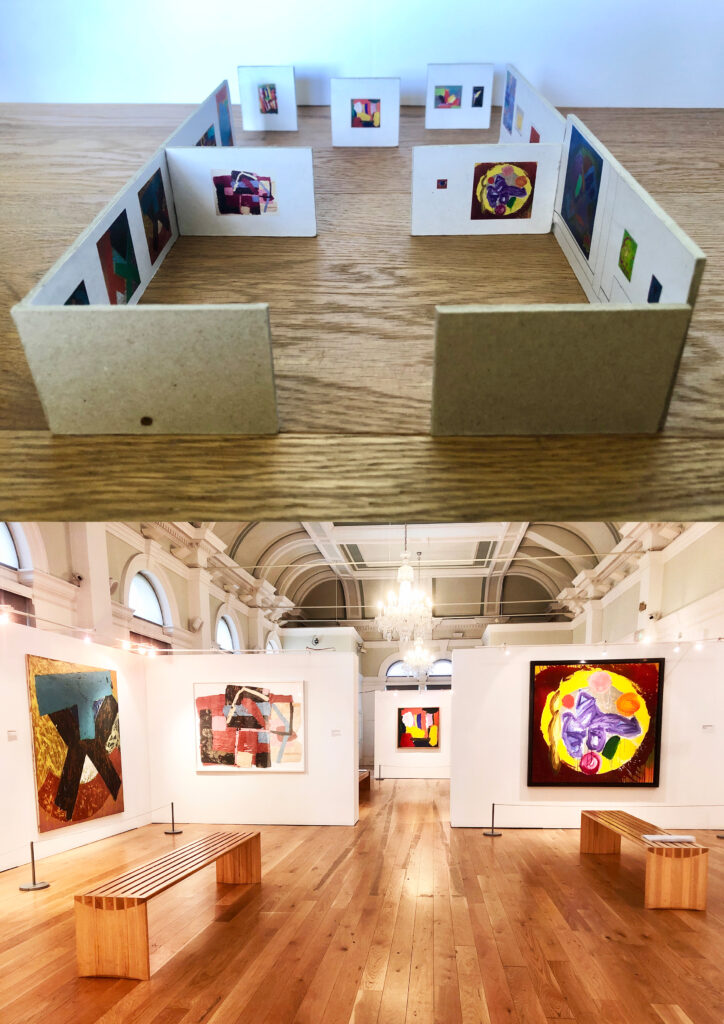

From maquette to Mercer: Top, the model layout for ‘Celebration’ (2022); Bottom, Installation view of ‘Celebration’, The Mercer Art Gallery, Harrogate, 2022

Not the most auspicious of times, you’d think, to be using the unmentionable, offensive ‘c’-word to provide the title for a survey of British abstract painting, and using it non-ironically to boot; but this, however, is exactly what curator Lee Taylor has done. And what’s more, ‘Celebration’, now showing at Harrogate’s Mercer Gallery, delivers on the implied promise of its name not just once, but twice over, by celebrating a strain of British abstraction which is also of its very nature unashamedly celebratory: to borrow from Sam Cornish’s description in his catalogue essay, the paintings in the exhibition are ‘positive, affirmative statements in light, space, and colour, and the materiality of paint and canvas.’

What’s remarkable about ‘Celebration’– not counting the cumulative effect of a polychromatic glow that fills the gallery spaces from end to end, generated by the deft hanging of a group of works that shares the preoccupations listed above- is how the collection that makes up the show came into being in the first place. Patiently, methodically, over two decades, without the clout of hedge fund capital or a major public institution to back him up, but with a cultivated eye for what coheres and convinces in a certain kind of abstract painting, Lee Taylor has acquired some fine examples- and a few first-rate ones- of work made by twelve British artists. The collection started small- at 20 by 25 centimetres, to be precise- with John Hoyland’s ‘Red Boat’ of 1998,3This wonderful small painting doesn’t feature in the show; but Lee produced it from a shopping bag over lunch in Betty’s, Harrogate’s famous Tea Rooms, so that Instantloveland could have a good look at it but has grown exponentially since, to the point where its reach and richness have made the telling juxtapositions on the walls at the Mercer possible: the stain and scribble of Gary Wragg’s ‘Dominant Yellow’ of 1977 next to the heavy, grinding, impastoed slabs of John Edwards’ ‘Green Tee’ and ‘Black Wedge’, both also from that year; the blurred and feathery blobs and spatters of gouache in Patrick Heron’s ‘June 16 1988: II’ against the hard-edged, almost-acrid, almost-cartoony intensity of the four colour-shapes that make up John Mclean’s ‘Glimpse’ of 2000; and the bringing together of two large works from successive phases of Hoyland’s career, ‘Harvest’ of 1981 and ‘Zoomin’ of 1986, the former all floating palette-knifed swatches and diamond shapes in suave pastels and primaries atop a stained blue field, the latter a huddle of splattered discs and urgent, bunched strokes inside a centred circle of yellow, laid on with a wide brush.

The collective jolt these paintings deliver can’t help but feel like an almighty shove back against certain assumptions that have spent the last few decades hardening into an orthodoxy. It’s now twenty-one years since Matthew Collings, in his ‘Rough Guide to Playful Thoughts on Abstract Art’4Collings, M., ‘Rough Guide to Playful Thoughts on Abstract Art’ in ‘British Abstract Art 2001’, Catalogue of the show at Angela Flowers Gallery, Momentum, London, 2001(which Instantloveland highly recommends, because it’s droll and deadpan and hilariously tactless in places, but nonetheless has some serious points to make) coined a set of categories for what he saw as the various modes of abstract picture-making. In brief, there were Hypers (all irony and doubt), Systematics (working to preordained sets of rules), Eclectics (mixing and matching modes); and then there were the ‘Authentics’, who ‘show their respect for an old-fashioned European art and US art. They try and think about what they can do now that still fits with that notion of something that was great but which they’re far removed from, in terms of time and place. Their paintings often have the look of tablecloths from the 80s.’5ibid.

Ouch. You could argue that the first two of those three sentences do the job- more or less- as a summing-up of the ‘Celebration’ painters’ shared concerns; but the swipe taken at their kind of painting in the third stands as a reminder of just how low ‘authentic’ abstraction’s stock had plummeted by the turn of the millennium. When you’ve hit rock bottom, though, where else is there to go but up? Not least when so many commentators on abstract painting have been putting in the work in recent years, arguing the case for the continuing importance of the sort of art featured in ‘Celebration’; one of the most notable, it has to be said, being Collings himself, who has freely owned up to having ‘lost touch’6Collings, M., ‘What Are We Looking At?’ in ‘John Hoyland: The Late Paintings’, Ridinghouse, London, 2021, p53with Hoyland in his excellent appreciation of the artist that appeared in the recent monograph, ‘The Last Paintings’. He argues that the work Hoyland made during the decades of relative obscurity that followed the fading of his art-world stardom now seems ‘rich and complex, unknowable, changeable, full of understated surprises.’7ibid., p53

It’s a fickle place, the art world; whether all these signs of renewed interest in a kind of abstract painting that has been consigned to its margins for so long now add up to anything more than what is known in the money markets as a ‘dead cat bounce’- where a stock that has hit the ground from a great height briefly rallies, before bottoming out again- is a question that Instantloveland wouldn’t feel comfortable attempting to answer. The fact remains, though, that on its own unironic, unabashed terms, ‘Celebration’ is a very fine show indeed, a labour of love, and Lee Taylor is to be congratulated for making it happen. Visitor numbers started high and have stayed high since it opened back in April, and that is surely something worth celebrating.

‘Celebration’ is at the Mercer Art Gallery, Harrogate, until September 4th 2022.