John Bunker and Phil Frankland: Casualism and its Discontents (with a Cameo by Frank Zappa and Lou Reed)

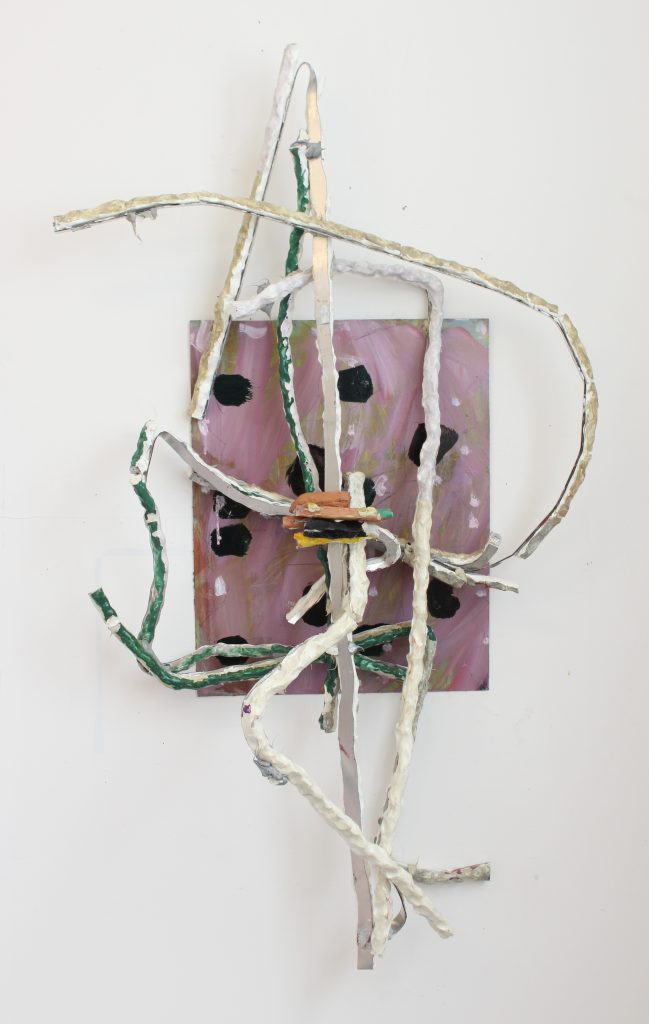

Phil Frankland, ‘Dent in a Two’ (2018), oil paint, gloss paint, air-dry clay, aluminium, glue and string on aluminium panel, 108 x 64 cm

PF: A great deal of discussion in recent years around painting, particularly non-representational painting, has been about identifying its relation to the screen. Painting on the whole appears to travel more or less in two directions – towards either the flatter, more screen-friendly; or the more materially tactile, even brutally handmade. As an artist who strongly relates to both notions of painting and collage, how do you see your work in relation to the screen?

JB: That’s an interesting question, because I hope social media, and the influence of the screen, might open things out a bit. On the whole, I think abstract painting now in this country has quietly maintained a kind of twee conservatism. I could relate that back through the likes of Hodgkin- an establishment figure, an artist overexposed in his own lifetime and bound to be overexposed again now he is dead. In British abstraction generally, small and generally harmless rules the day.

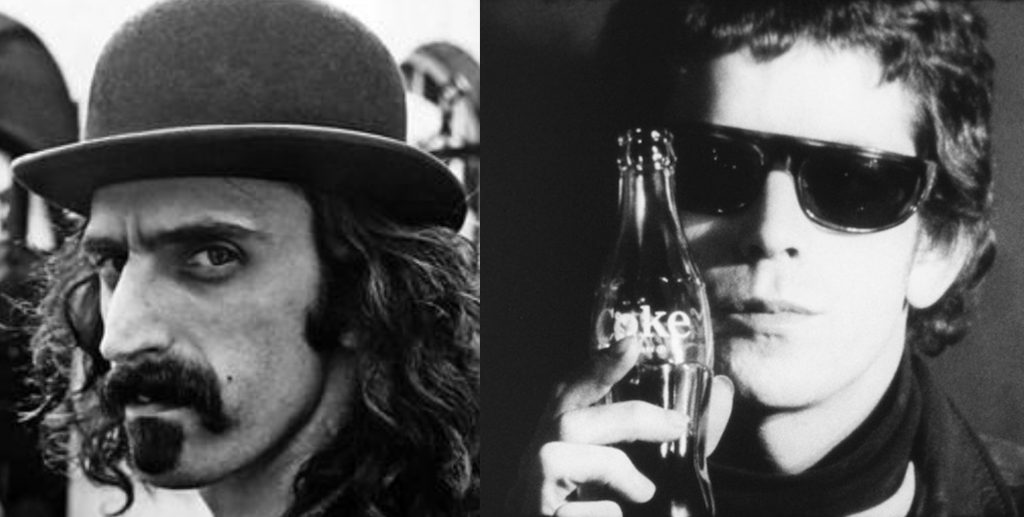

I met a really nice singer-songwriter the other day. She’s doing well, being noticed by well-respected music critics. She recently received a ‘newcomer’ award and is getting chances to perform with the highly respected elders of a certain musical tradition. I was impressed by her knowledge of, and commitment to her form; but something troubled me about our conversation. Later, while pondering on why Lou Reed and Frank Zappa hated one another for so long, I realised what it was: certain traditions in popular music make their cyclical return as a cultural ‘moment’ every so often; and I couldn’t help but see parallels between these supposed rejuvenations of traditions, these ‘revivals’, and recent developments in my own chosen art form. I often see art that has no real criticism to make of the tradition from which it has sprung. I’m getting used to seeing art that is neither suspicious nor critical enough of its own history to make anything interesting out of it.

L to R: Frank Zappa – Horse Guards Parade, London, 1967; Lou Reed, Still from Andy Warhol’s ‘Screen Test (Coke)’ (1966)

This kind of rustic, say-it-how-it-is, neatly-crafted eulogising- a sort of well-meaning folk abstraction- is on the up in the small world of contemporary British abstract painting. There’s a kind of tipping-of-the-cap indulgence of historical figures, and a painfully dull re-romanticising and sentimentalising of the ‘creative process’ going on. I hope the rise of social media and the fascination with screens has put a spanner in the works. I hope it gets abstraction out of these kind of ruts.

PF: Secondly, as an artist who has experienced the growing influence of the internet, the screen and online ‘marketing’ (for lack of a better word) – I’m thinking here about websites, social media, online visibility – how have these changes impacted on you?

JB: Huge changes in the last ten years, for sure! Some really good, some not so good…I became very aware early on, how certain artists are taken up by certain galleries after completing certain courses. You only have to consider a selection of artists’ CVs from many middlebrow galleries to recognise that they all have attended, the same three or four institutions. This fine art version of the Oxbridge syndrome is leading to an ever more divisive and elitist outlook in art education, which is echoed in the higher education sector generally. Institutions compete for the right kind of students; and rich overseas students figure pretty prominently in their dealings. These wealthy wannabe-artists are then bankrolled through the tough post-college period by rich parents or ‘patrons’. They network with the same privileged classes that run the galleries they would like to have represent them; and so the fine arts merry-go-round churns out the same old rides while piping out the same old tunes. I mention this because I didn’t have a great relationship with the education system the first time round. Anyone who is not in this feedback loop is looking for alternative ways to get work and ideas out there. My work definitely evolved in the kind of taut atmosphere that existed in online debate outside the education system.

Since the financial crash, many of these middlebrow galleries have closed or streamlined their businesses. I think it’s created some interesting challenges for privileged artists. They can’t rely on middlemen in quite the same way. They occasionally have to rub shoulders with the likes of me these days. I use social media to promote shows and I write about art on various websites. I’m very aware that I do it badly! If you are not much interested in academia-orientated career routes and class-bound nepotism, then where does one go to create meaningful dialogue about art and about possible new developments in one’s work, outside of academia, private art schools or the commercial gallery sector? Social media has allowed the building of support networks and the sharing of knowledge between individuals and groups that have bypassed or undermined the processes of mystification that so many galleries have relied upon to create market value for their ‘products’.

How do you navigate the transformed social contexts that frame the production and consumption of your paintings, Phil?

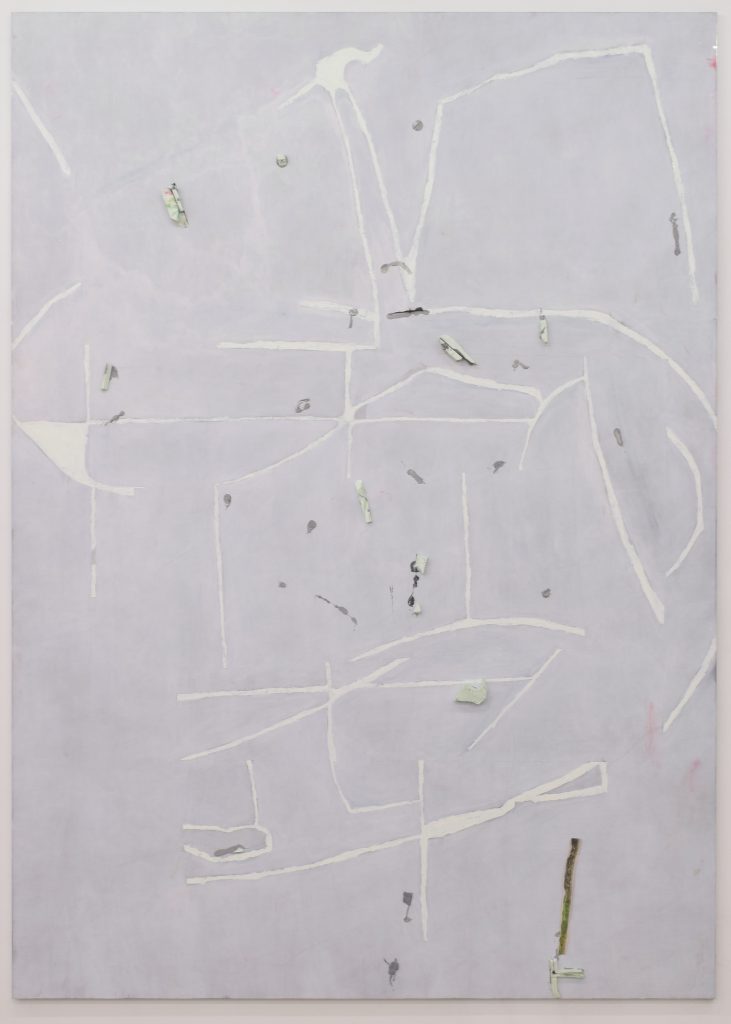

Phil Frankland, ‘Little Twitch’ (2016), oil, air-dry clay, gloss paint, glue on aluminium, 210 x 150cm

PF: I hope that social media does not deter people from setting up small, independent zines and pop-up galleries/artist colonies which still promote freshness and tactility in art. I guess my worry is that social media deters audiences from attending galleries, which is also ironic, given that it makes events and galleries more visible than ever. What are your thoughts? Does social media have a sterilising effect?

JB: Yes, there are big pros and cons to social media, of course! But I was brought up on listening to post-punk music, and inherited its DIY aesthetic and approach. I was also brought up on a working-class housing estate, listening to older mates’ punk records and northern ‘Indie’ music in other peoples’ houses. What if I can’t afford to do an MA and then a PhD, or to attend conferences that simply tick boxes in the world of academia? If none of these academic options are really open to me, then where do I go? Where do I go for art? How do I make art? How do I show it? How do I find out about other people’s art? How do I find out about artists who share my concerns about the state of it all? Well, I go back to my roots….

PF: I am still rather fresh from art school – I only finished my Master’s last year at KASK, Belgium, and my BA at Newcastle three years before that. In the two years inbetween studying I worked as a bartender in the evenings, while allowing time during the day for the studio, and for various positions as an artist’s assistant. I found these two years very useful; and they taught me a lot in hindsight, not only about my practice (I basically spent the two years trying to wrangle my way out of lots of art school pitfalls) but also about my motivations. Doing the Master’s, I found that the previous two-year chunk of time had actually taught me more than I had realised, and this put me at loggerheads with a few of the teaching staff.

Art schools spitting young artists straight into the galleries is definitely problematic, but as you suggested, it keeps the system ticking along, albeit in a way that is perhaps very unhealthy for the growth of really investigative, risky and surprising art. One would think that the sheer numbers of visual artists and students coming from art schools nowadays would negate the idea of ‘trend’ or ‘movement’-related artists. But perhaps certain schools have a history of ‘success’, and therefore they are producing the most ‘current’ artists. This then makes it easier for galleries to snap up young folk fresh out of art school. In reality, young students and post-students with enough money can build works at any size they want and live in a prepaid flat. But do they carry the same motivations for becoming artists as others who are working 4 days a week just to afford basic oil paint, small painting supports and rent?

I am aware of the sort of abstract artists you mean when talking about small, shy sizes and modest, inward-looking conservatism. I feel that we are slowly creeping away from that sort of painting now, which is a relief, in my opinion. I wrote a thesis last year about Casualism, and it definitely made me question whether a sort of Casualism operates in British painting, but in a slightly altered form to the American variey. I felt that the motivations behind Casualism were perhaps more innocent, than vacuous or brash. The whole thesis left me with more questions than answers, and stirred up a lot of thoughts with regards to labels, trends, groupings and pooling of artists in today’s art world.

JB: I’m intrigued by your scholarly interest in Casualist painting. What was your motivation for writing on it? What conclusions did your draw from your study?

PF: I guess I was initially quite interested in the aesthetic of it before anything else. I felt that it very much ran parallel with my practice, in terms of engagement with materials and sources, and the role of the ‘support and surface’. My first contact came through reading Sharon Butler’s ‘A Casualist Tendency’ and then, after that, Raph Rubenstein’s ‘Provisional Painting’. Only after more sustained reading did I become aware of the negative aura that the ‘movement’ (for lack of a better word again) seemed to be acquiring, especially with regards to its associations with young, get-rich-quick art dealers; and the fact that a lot of the work was just really, really bad, instead of ‘good bad’. Was slap-dash, lazy painting always slap-dash and lazy? Could its motivations be attributed to something else? I was drawn to the delightfully ironic and hypocritical feel of it all! Bad artists making bad art in good schools to sell to good galleries. I felt torn between either believing that Casualism had genuine worth as an attitude and response to painting in the 21st century; or that it defined everything that was potentially wrong with the intentions of the young, self-interested and materialistic artist.

My thesis centres around two texts, both by American critics, which attempt to hypothesise why Casualism had sprung up in such a big way. My interest was to see how I related to these hypotheses – basically to see whether I myself could be defined as Casualist or not. The thesis talks a bit about this university-museum-gallery complex that we touched on in our first emails. I talked about the situation of the young artist as time-limited, studio-limited and constantly fed with information from one source or another. Are the small size and speediness of Casualism just a side-effect of increasingly squeezed resources of time and space?

What struck me in both a negative, and a positive, intriguing sense was the idea of defining the ‘movement’ – I read lots of articles where artists with similar aesthetic outcomes were being book-ended together without much apparent investigation, in an attempt to quell the need for herding artists into neatly-titled pens. I felt strongly that throughout my investigation, waters were getting increasingly muddied. By the end, most artists from the last 60 years had been given roles in the forming of Casualism, in one way or another, by one critic or the next. I couldn’t find much correlation between what some defined as Casualism, and they artists they labelled as such.

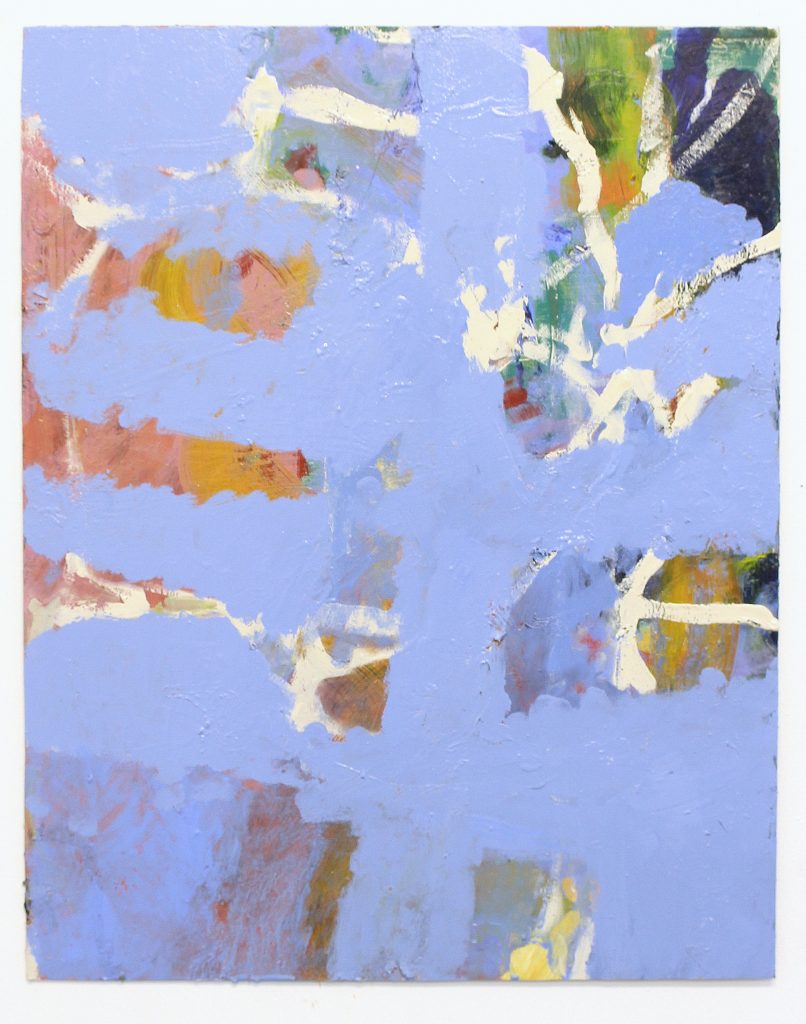

Phil Frankland, ‘London Zoo’ (2017), oil, oil stick, Styrofoam, glue and digital print on aluminium, 210 x 150cm

By the end of the thesis, my only way to try and deal with what I felt was snowballing into 10 different texts was to examine justifying my own position and practice, with relation to ‘Casualists’ as identified in Butler’s initial text. The last part of my final chapter reads as below:

I find myself empathising with the associations of Casualism, yet ultimately feel guilty for it. The idea of working hard towards something which is disregarded as just any other young painter’s folly is perhaps both a fault of myself and the critics who have confronted the subject. If rebellion is no longer possible, then the only approach left is acceptance. This is where tarring artists with the same brush becomes irresponsible. In an email interview I recently conducted with Alan Pocaro, he also stated his wariness of umbrella definitions, suggesting that ‘the diversity of artistic production is so great that one can ‘cherry-pick’ any number of painters that fit one’s preconceived notions about ‘contemporary developments’. The idea of trying to define a present movement or ‘ism’ needs the benefit of hindsight, otherwise it relies too heavily on justification or biased labelling. To leave criticism of Casualism ‘unfinished’ for now is perhaps very apt.

JB: It’s always interesting to look at the bigger forces at work in the national mindset, no? Its no suprise that austerity Britain should have its own austerity abstraction to suit? There’s the ‘make do and mend’ mentality but there’s also a kind of puritanism behind the neo-formalism at work too. Is there a re-emphasis on abstract paintings’ relations to poetry and music, a turn toward reification and reduction- the lyrical ‘I’ or ‘look at little ol’ me, me, me’ on Instagram, Facebook etc? Are these kinds of abstractions simply covert self-portraits, or selfies, even? My problem is with how quickly a reevaluation of formal properties of painting acquires tones of po-faced worthiness, and even intimations of the spiritual. In this respect I might have some sympathy for the more irreverent ‘up yours’ aspects of Casualism. Abstract art has always had this relationship with spirituality, though; and I’m not surprised by a subtle reemergence of ‘nature’, or some idea about emotions as a kind of half-buried or ‘undead’ subject matter underpinning this kind of abstraction. I keep saying one should look outward as much as one looks inward, no? I wonder if that is why I consider the collagic impulse as central to my work? I remember being in a crit where a particular artist was presenting large (for a change!) dark paintings in which over-large swirling brushmarks arched and twisted their way up through the centre of the paintings. The simple illusions created by the expensive and large brush moving in carefully choreographed sweeps across the canvas in fleshy tones were immediately dramatic but in my opinion hollow and overblown. I asked if he’d spent time with Lichtenstein’s ‘Brushstroke’ of 1965, or David Reed’s work. I was looked at by him, and by my colleagues in the crit, with horror. ‘We don’t do postmodernism and irony here…’ was the general vibe. But the work was limited by its outmoded ideological boundaries. You have to raise your game and deal with art that questions art. You deal with it by knowing it. The best art does this, in my opinion, and always has. These crit people suggested that art testing art is an end-of-century thing, and somehow done in bad faith. No. It is not only a postmodern thing. It’s been around for as long as the consciousness of being an artist has- and it is neither inherently good nor inherently evil.

And that makes me think about Lou Reed and Frank Zappa again. The basis of their mutual mistrust might have been born of Reed’s insistence that Zappa’s music was not authentic enough, it wasn’t real rock ‘n’ roll; whereas Zappa was saying, no, look at the corrupt machine behind the art. In his music, Zappa began to reference the industry operating behind the scenes; that was surely real? He made us watch as rock ‘n’ roll became a sad parody of itself, and he brought that reality to us. At their best, I prefer the Velvets and Lou Reed, though: because they found a way to internalize and meld these sort of tensions; maybe? But here we are, well into a new century, Phil!

5 thoughts on “John Bunker and Phil Frankland: Casualism and its Discontents (with a Cameo by Frank Zappa and Lou Reed)”

Comments are closed.

Excellent discussion – right on!

My favourite, era-defining question: ‘Is there a re-emphasis on abstract paintings’ relations to poetry and music, a turn toward reification and reduction- the lyrical ‘I’ or ‘look at little ol’ me, me, me’ on Instagram, Facebook etc? Are these kinds of abstractions simply covert self-portraits, or selfies, even?‘ posed by JB.

Covert selfie, good point. Still not sure what Casualism is(after Punk but before Mod) need to investigate further.

Perspicacious.

I think you are spot on when you state that “the idea of trying to define a present movement or ‘ism’ needs the benefit of hindsight, otherwise it relies too heavily on justification or biased labelling. To leave criticism of Casualism ‘unfinished’ for now is perhaps very apt.”