Michael Stubbs in conversation with John Bunker

Michael Stubbs, ‘Velocity Acceleration Reflector’ (2016), household paint, tinted floor varnish on MDF, 122 x 122cm

At the end of last year I wrote, in a review of a contemporary abstract painting and sculpture show, that ‘Figuration has been constantly re-invigorated, first by photography and now digital imagery of the body and beyond. But what about abstract art? It was artists like Peter Halley, Jack Goldstein and others from the Neo-Geo/Appropriation generation who forced abstract tendencies in art into new relationships with reality and with representations of that reality.’ 1Bunker, J (2017) Some Thoughts on ‘Sea of Data’, just finished at Unit 3 London. AbCrit. https://abcrit.org/2017/11/11/84-john-bunker-writes-on-sea-of-data-at-unit-3-london/

So what has changed in abstract painting since the 1980s? If we have moved on from what some might call the ‘end games’ that became synonymous with Postmodernism’s parodies and ironies, then where might abstract painting be now? Via our highly mobile screens, we can search out almost any kind of representation of anything at all, from seemingly all-seeing and all-knowing conglomerations of big data. It might be argued that there are historical instances of abstraction, both geometric and hard-edged, and of gestural sign-making, that lend themselves to the visual experiences we associate with the screen. So what happens when the digital realm impinges on abstract painting? How does the artist’s and viewer’s sense of agency and subjectivity change in relation to painting if it is somehow mediated by a screen?

According to the precepts of late modernism and formalism, painting must undergo a process of being hunted back to its essential qualities as a medium and an object. Now, by contrast, painting in an expanded post-medium phase is able to reconsider and reclaim its agency as seen through, and in relation to, other mediums. If, as Isabel Graw says, ‘We conceive painting not as a medium but as a production of signs’ 2Graw, I. (2012) Thinking Through Painting. Reflexivity and Agency Beyond the Canvas. p50. Sternberg Press. then paintings are opened up as complex visual structures, full of historical references and linguistic turns. Here, there is no single essence of painting, but a series of overlappings, slippages and collisions of positions. This chimes with an attitude to images and their manipulation attuned to our digital era; one in which it is possible to see a certain kind of contemporary abstract painting working as optical ‘search engines’, mining the imagery that traverses the real and the virtual.

Michael Stubbs has developed an approach to abstract painting that inhabits this territory, and thrives in it. What follows is a free-wheeling discussion, (although we attempted to keep these issues anchored in the reality of Stubbs’ painting process) covering some of the theoretical positions that seem relevant now in discussions about abstraction. We have used sub-headings to highlight those parts of the text that consider these positions as the discussion ricochets between topics.

John Bunker, 2018

—————————————————————————————————————————

JB: I’ve become aware recently of a re-emergence of a kind of attitude to painting that reasserts a notion of self at the centre of making. There seems to be a drive toward the lyrical impulse – a need to put the ‘I’ back in the creative process: the intimations of poetry come to mind – or a renewed interest in notions of authentic experience of nature for instance? Is this a reaction to the overarching narrative of technology supposedly driving out the possibility of authentic experience? Is this reassertion of the ‘me’ in all this an attempt to wrench back into painting a sense of something that can be ‘truly’ experienced or felt?

MS: Yes, but it’s debatable that this notion of ‘I’ has ever not been present in recent painting. I think we’re already on dodgy ground here. I’m very wary of claims, though, for an essentialised centre of the self, I’m arguing very much for the opposite. We are far more fragmented. We don’t have that holistic sense of self that comes from Enlightenment thinking whereby metaphysical philosophers like Kant argued that aesthetic taste and judgement are transcendentally exempt from pure reason. So although the ‘I’ has always been there, I’m more interested in those philosophies that critique the metaphysical. Specifically, what you are talking about is a generational thing. At Goldsmiths in the late 80’s we were taught to deconstruct linear, uncritical narratives. We were asked to question notions of the author as the ego-subject, or of the sovereignty of self. I think it’s still being questioned, but in richer and more interesting ways.

So, clearly, I’m not for returning to an unquestioning or unquestioned ego-driven painting. I see painting now as an exploration or an extension of a critical undertaking. It might come from a deconstructive way of thinking but without the limitations of dogma. Deconstruction can feel like you get to a certain point and you come to a standstill. You tick all the theoretical boxes, but then what? Lots of full stops! Other areas can be opened up; and this is about seeing one’s self in relation to a bigger world, the world out there…. There’s nothing particularly innovative about that. But I think, for me, subjectivity in art has gotten far more complex. We’ve moved through critiques of the sovereign self via post structuralism, deconstruction and post modernism. But I think there is a reappraisal going on that focuses on how the agency of subjectivity operates, especially in relation to painting.

JB: As you have hinted at there, we do share an outlook shaped by an arts education that foregrounded the questioning of the artist’s relationship to the wider culture; and this would inevitably lead us back to subjectivity. It was asserted that selfhood was intensely mediated by societal pressures, the ideologies that underpin it, the institutions that organise our experiences, the images that permeate and regulate our desires and sense of self. We might see these ideas in Debord’s ‘Society of the Spectacle’, for instance.3Debord, G (1970) The Society of the Spectacle. Black and Red. A pdf of Black and Red translation of The Society of the Spectacle. Unauthorised. Detroit 1970 https://library.brown.edu/pdfs/1124975246668078.pdf This of course tallied with aspects of deconstruction and semiotics presented in Barthes’ ‘The Death of the Author’,4Barthes, R (1977) Image, Music, Text. p142. Fontana Press. A PDF of Barthes, R (1977) Image, Music, Text. p142. Fontana Press. https://grrrr.org/data/edu/20110509-cascone/Barthes-image_music_text.pdf where he opens up the idea that the writing of a book is just one part of a complex relationship between author and audience. In terms of art, we might apply Barthes’ idea in saying that the viewer is co-creating the artwork in their experiencing it; they are carrying out the work of realising it as much as the maker/author.

MS: 50% author, 50% viewer.

JB Yes, and this is something you bring to the fore in your practice…

MS. Yes, but I’m not the only one here! We’re running on this awareness which comes out of all these theoretical influences that mark out the role of the audience in constructing meaning…

Re-Investigating ‘Medium Specificity’

JB: This ‘audience friendly’ approach complicates and loosens the closed loop created by adherence to medium specificity– the endless call and echo between the artist and the medium?

MS: Well, that’s Clement Greenberg, really, and his quest to separate out the arts, with painting being in the highest position. This is not only limiting; it reduces our ability to read the work if we are only allowed to see it in relation to the medium. This is all arguable, but we know these discourses. All this has been deconstructed to death. So my next question is how to and why continue to make paintings?

JB: And to try and keep the discussion focused on the work itself, we come to the idea of bringing in these anterior images, materials or other mediums into painting… So in your own work you have created a painting process that is about collision. On the one hand we have this Greenbergian idea about the properties specific to painting, like flatness for instance, and the tropes of the art made around this discourse, such as the pour. You clash this with a completely different sensibility; a cultural awareness that comes through Pop and was seen later in postmodern art. I guess it was there in Dadaism and Surrealism too. But then there was this constant agitation against or undermining of notions of high art, high culture and high minded ideas about aesthetics. But in pop there was a new kind of ambivalence. All the agitation had drained away. Warhol would become the master of this. He and others constantly chipped away at this essentialism and sense of self that seemed to be prevalent in the approach to painting exemplified by first and second generation ‘Ab-Exers’ and the ‘Post Painterly Abstractionists’. Warhol quipped about there not really being much to him. There really wasn’t much ‘self’ at all… He was all surface.

MS: Yes, but these are mythologies based on historical givens as well, though. These are old-fashioned narratives, aren’t they? But I like the word ‘collision’ because it brings in the notion of cut-and-paste, where digitally, you can cut and paste together whatever you fancy, whatever you find from whatever era. Now look at this press release for ‘Forever now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World’. It says that:

‘ Painting now is a ahistorical free-for-all; where the historical legacy or mixing of styles or genres means that sampled motifs morph and collide to reshape historical strategies like appropriation and bricolage which in turn asks questions of originality and subjectivity.’ 5Hoptman, L (21040 ‘The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World’ MoMA Press Release.

That was written in 2014 or 2015 for the show of the same name at MOMA, New York. But I could easily have read that in 1982! It reminds me of the postmodern works of David Salle, or Sherry Levine. The quote is postmodernism re-branded.

JB: What’s fresh here?

MS: To say that we are in an ‘ahistorical free-for-all’ for instance isn’t exactly new but it does perhaps register a place we are in now – and have been for some time – where we can sample from wherever at a new pitch and intensity. But now listen to Mark Godfrey’s press release for recent Tate show ‘Painting After Technology’ where he invites us to contemplate that:

‘Digital technology has transformed the ways in which images are created, copied, altered and distributed. Tools such as photocopiers, scanners, iPads and photoshop have provided painters with a range of new possibilities.’ 6Godfrey, M (2015) ‘Painting After Technology’ Tate Press Release.

JB: So maybe ‘Forever Now’ is a bit of a rehash of older ideas; but Godfrey at Tate is talking more specifically about the bigger technological changes that allow us to manipulate imagery and receive imagery. So is this key to your process?

‘Being in Painting’

MS: Perhaps yes, it’s important especially as an examination of a medium; but it still begs the question… Why make a physical painting? Godfrey’s assertion seems to ask how technology affects the medium’s (or mediums’) construction, and how we are reading painting. And equally, where painting’s privileging of the subject now resides? Or to put it another way, what does it mean to be in painting? Now, being in painting could take us back to a Greenbergian modernism again, as we said; or to the artist finding identity in painting through the medium as the translator of expression. I think it’s worth re-examining painting’s mediums, but without the value systems of Greenberg’s Modernism. One way of doing this perhaps is by utilising those ‘anti’-modernist ideologies (or tropes) such as Pop or Postmodernism. I think there is an overlap between these positions. I see this overlap a lot in students. I think they have a love/hate relationship with contemporary technology which can lead to reaction against the digital: Instagram, etc., and the overarching reach of image saturation. My students often want to physically make stuff because it gives them a powerful sense of the real. You and I might question that logic; after all, what constitutes the real but a series of linear ‘hand-me-down’ enlightenment philosophies, which was subsequently followed by Post-structuralism. But I think this desire for a sense of self, not as an heir to essentialism or the full stops of deconstruction, needs to be examined. How can painting now allow for a sense of the subject?

I think this allows us a way in to the complex relationship between being in painting, and making painting. But this may also help us to explore the complex interplay between how we receive information via the screen, social media and multi-platform networks generally, and material making; how the subject resides in simultaneous places at any given moment and the fact that painting can reflect this? It’s important, because somehow you then still believe in painting’s histories whilst at the same time acknowledging the contemporary world. This is not a ridiculously outmoded myth; the physical desire to make is still there, except now there is a more knowing manipulation of how art history, subjectivity and making act as tropes to ‘signify’ subjectivity. The author can only be read in the surface of the painting but at one knowing remove.

Michael Stubbs, ‘Speculative Immersion Sensation’ (2017), household paint, tinted floor varnish on MDF, 153 x 122cm

Material Making

JB: I do think that cuts to the quick of things that can get easily lost in generalisations when we talk about the impact of technology and selfhood. Maybe there is a more urgent desire to attempt to articulate a sense of self because of the sheer deluge of material that comes our way via all the media available through all the varied screens we interact with. In terms of painting, authorship and subjectivity, you recognise that self is a complex interweaving of social values and ideologies and that there are conventions that guide us almost unconsciously; as explored by Althusser.7Althusser, L. (1970) On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. Verso Books 2014.

MS: Yes, for me it’s about knowingness, and about being familiar with painting’s histories, including recent history. But ironically, I make like a formalist painter… I honestly do. I enjoy those kinds of decisions – a red here, a green there… But I also try to mess with my own understanding of formalism. Besides, I have no historical relationship with the values of historic formalism, even though I’m familiar with them as given tropes, but I’m perfectly prepared to steal from its tropes of discovery through the act of making. And once you’ve accumulated this kind of knowledge, it helps to forget it when in the studio in order to put yourself into a mind-set that allows for Andrew Benjamin’s notion of ‘the becoming, yet-to-be-resolved object’.8Benjamin, A (1996) What is Abstraction? Academy Editions. Using a different side of my brain I guess means that knowledge is implicit and consciously understood in my rational part; but making is irrational, it overrides self-consciousness and allows for accident, collision, colour and formal choices.

The Process of Painting

JB: So you are talking about subjectivity or sense of self as bound up with the act of making, the sheer enjoyment of the process of painting? It’s the driver, the motivator? And this comes first?

MS: I’m not sure about the word ‘enjoyment’, as it can be very difficult too… But it is a process of discovery and I happen to be a process-based artist. I do one thing after another thing, building up layers. And I’m always amazed at what I discover.

JB: So the emphasis is on discovery…

MS: Visual discovery…

JB: The emphasis is on the relationship with the mediums in play. Very Modernist then?

MS: Yes, but there is also all the other stuff that comes at us from the screen. We are routinely overwhelmed with imagery but I’m also interested in the colour and flatness of the screen…. Look, these art historical narratives of Pop or Greenbergian Modernism have been pushed together and pulled apart by artists working with a ‘knowingness’ about the tropes of abstraction for 30 odd years, a process which I consider I am a part of. I’m interested in focusing on particularities that are particular to me, and that I’ve developed in my process of painting. So, I’m using imagery I’ve sourced from the net, clip-art and screen icons, which I then have blown up and made into stencils, which then are layered into the painting process. They have some kind of initial narrative content for me, perhaps, but they act in the service of the form of the painting and often get buried as image/signs throughout the process. They become part of the form of the painting and not its exclusive content.

JB: So you are organising and structuring as you go along. You are emphasising the visual qualities of the painting. You are using these qualities as guiding principles. But at the same time, you are layering imagery. You are creating what is essentially an archaeological site. You will lose track of the materials you have been burying over a period of time. Then you go through a process of removing the layers, subtracting from the painting’s surface. Through this process new possibilities arise, the ‘discoveries’ you talk about are made. Is there an attempt to recapture a sense of spontaneity here?

MS: Yeah, but at the same time though, the value system with which I choose to articulate that notion of discovery or spontaneity is entirely different from the monocentric, internal reality of Modernist/Formalist artists. However, of course painting is a reflection of oneself, it goes without saying. But I’m interested in acknowledging a bigger, representational world of signifiers that impacts upon your sense of a subjective self.

Simultaneous Ecosystems in Painting

JB: John Chilver wrote about what he saw as distinct ecosystems operating in your work.9Chilver, J (2010) Decorative Delirium. Laurent Delaye Gallery. http://www.michaelstubbs.org/michael-stubbs-decorative-delirium/

MS: Well, when you cut and paste things together you get this colliding of different ecosystems. If we break the painting process down for a moment, you could see one ecosystem as the flat opaque paint- household paint; another ecosystem would be the transparent household varnishes, another would be the set of symbols or signs which are stuck on and removed. Spray paint is another ecosystem. Then you have another system which represents what those signs and symbols mean in the world. Then you have the high-minded ecosystem all about painting and its histories. Then, on top of that, we have the social realms created by our interface with the screen; and all these ecosystems, for me, collide with one another in the painting. They are distinct, but they only have agency in conjunction with each other. It could be like language and the process of constructing a sentence. One word operates in relation to another to create legible meaning, although in isolation that word has no context.

JB: So are you bringing all these things together to create a larger reading?

MS. Well, all these things are operating under the umbrella of opticality in relation to physicality. The opticality means you can see through the transparent layers of the painting – you talked earlier about archaeology. Then there are the physical qualities of overlaying that make you want to touch the painting. So there’s this interrelation between the optical and the physical. These qualities are exaggerated in the work, but through the use of utilitarian materials like household paints.

JB: Chilver’s ‘ecosystems’ give us a perspective on painting as a site of complex interactions of opposing positions, or a recognition of the fact that painting is able to hold onto a kind of simultaneity, a divergent range of materials, perspectives and ideas…

MS: I must keep bringing this back to the making of paintings. Deconstruction and postmodernism are essential precursors to understanding where painting is going. Critics and academics are always very keen to find the next big thing; to pronounce that something has finished or is dead and something new has taken its place, but I’m interested in overlapping positions. How subjectivity is ontologically informed by material conditions and social contexts via the ubiquitous screen, pop culture, capitalism, the power of images and branding, and so on. How is this translated into our experience of 21st century painting and its making. And how is the subject transformed by these interrelations? What we have now is an expanded and complex set of ongoing questions.

JB: So, this jostling of positions, these different languages of painting that co-exist in your work, are they attempting to get beyond subversion for its own sake? There is a lot of movement in your work, a lot of formal innovations that seem generated by this archaeological layering. Do you feel you are trying to move your painting beyond the theoretical limits of postmodernism?

MS: But isn’t that just another aspect of a binary argument which was one of the problems with postmodernism’s opposition to modernism? What is all this about having to ‘move painting on’? Isn’t that just like the fashion industry, or the fashion industry of art? ‘We must move forward’ is straight out of the stories of progress in art history. Art history has flattened out now. I’m interested in an understanding of art that spreads laterally rather that top down. I find myself making in the midst of this lateralness.

JB: When you say flattened out, do you mean hierarchies within art have been flattened out by our questioning and revision of art histories?

Decorative Delirium

MS: Well, we’re so familiar now with these histories, and with seeing very old paintings and very new paintings in many different contexts. This lateralness is something I want in my paintings. But there are other important factors that I want my work to explore; like sensuality and decoration. My uses of household materials reflect this. Decoration can be seen as anti-modernist; for example in a Kandinsky or a Malevich painting, the notion of a ‘hard won, formalist’ composition is played out. But arguably we can shift those values to read their works as purely decorative, as the meaning systems of formalism are very limiting. Do Malevich’s colours really hold spiritual power? Of course not! They do work as decorative arrangements that may create a sensation or a feeling in the viewer though. Recent painters such as Polke knew that; Oehlen knows that, Fiona Rae knows that. We have revised and critiqued modernist value systems with the knowledge of their loss. What I hope to get into my painting is an attempt to locate the subject or the author in relation to three concerns; received imagery, notions of the historical in painting and the act of (decorative) making. I see it like putting a jigsaw together, like a game of decoration. So that is another factor that comes into my understanding of making. There’s this self-conscious knowing which has limits to it in terms of historical interpretation; but limitless if we include social factors.

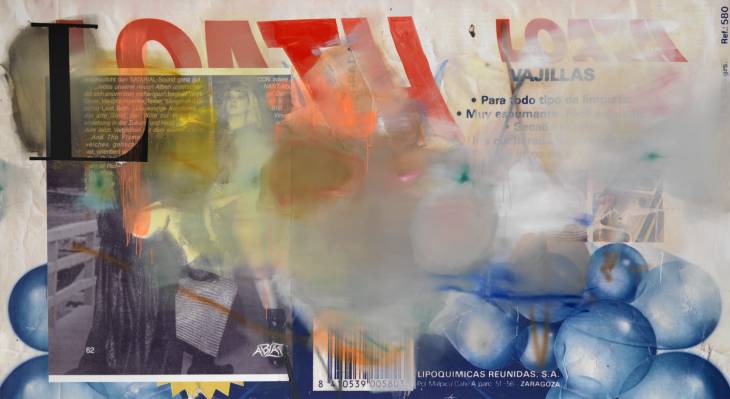

Albert Oehlen, ‘Loa’ (2007), acrylic paint, ink, photograph on paper, spray paint and oil paint on canvas, 170.2 x 310.2 x 4.1cm

So again, why make paintings? Well, they are a form of expression that can affect a viewer. I do it in a way which is obviously decorative and physical. They are sensual and seductive. Audiences don’t necessarily want this. A lot of people like a bit of angst. I self-consciously work against that in order to explore the sensation of utilitarian aspects of paint and decoration; they reflect upon the idea of the screen.

JB: Craig Staff talks about how the digital finds its way into painting by the ‘imaged’ where actual digital prints or other media are prioritised; or in the ‘imagined’, where digital imagery is recreated or referenced in painterly form.10 10. Staff, C (2013) After Modernist Painting. The History of a Contemporary Practice. I.B. Taurus & Co Ltd. You work both with vinyl stencils of images gleaned from the screen (what Staff might call ‘imaged’) and paint, which might be in his ‘imagined’ category? You use both approaches. Or do you see it differently?

MS: I’m interested in making painting as a bodily experience but I’m also interested in something that has been electronically rendered. I see this as a new site of potential for painting. I think it reflects the sense of self or subjectivity in making painting now. I see a flattening out, a lateral way of thinking and being in painting that includes positions or identities that overlap or collide or slide over or under each other. So when you make a painting you have to negotiate the embodied materiality of painting but also the disembodied imagery of the screen. Whether utilising physical gestures or electronic substitutes, I think painting kind of mirrors how our consciousness – our subjective sense of self – attempts to construct patterns of behaviour out of myriad codes of desire as mediated by technology.

JB: I think you are navigating how we might be experiencing, thinking and feeling about imagery via the screen. And you are suggesting how painting might operate differently now to how it might have done in the past, culturally. Or there are connections to the past or ways of critically exploring painting’s past that could open up possibilities for the future… It is interesting how you frame all this in the desire to make.

MS: I want to critique the clichés about being an artist in relation to the overabundance of our hyper-networked world, so as to better understand the sense of, or desire to make, paintings. You may want to focus on the screen as your painterly inspiration; or alternatively, you may want to hang onto the value systems of past formalism, in order to reject the screen. That is all fine, but you can’t just reinvent painting via all the romantic clichés, the screen is part of who we all are. You’ve got to ask questions…..

Michael Stubbs, ‘Dilator Head’ (2013), household paint and tinted floor varnish on MDF, 61 x 51cm

Illustration from A Black and Red translation of ‘The Society of the Spectacle’ by Guy Debord, Unauthorised, Detroit 1970

Front cover of Black and Red translation of ‘The Society of the Spectacle’ by Guy Debord, Unauthorised, Detroit 1970

One thought on “Michael Stubbs in conversation with John Bunker”

Comments are closed.

Really enjoyed reading this conversation between Michael Stubbs and John Bunker.

MS made some really considered points about the formal aesthetics of painting, the embodied knowledge within the act of painting and the screen being the disembodied. The virtual space of the screen for contemporary artist has become a visual pick n mix library for inspiration but also it can be overwhelming and overloading.