Charley Peters: Genital Panic: Abstraction by Women in ‘Surface Work’

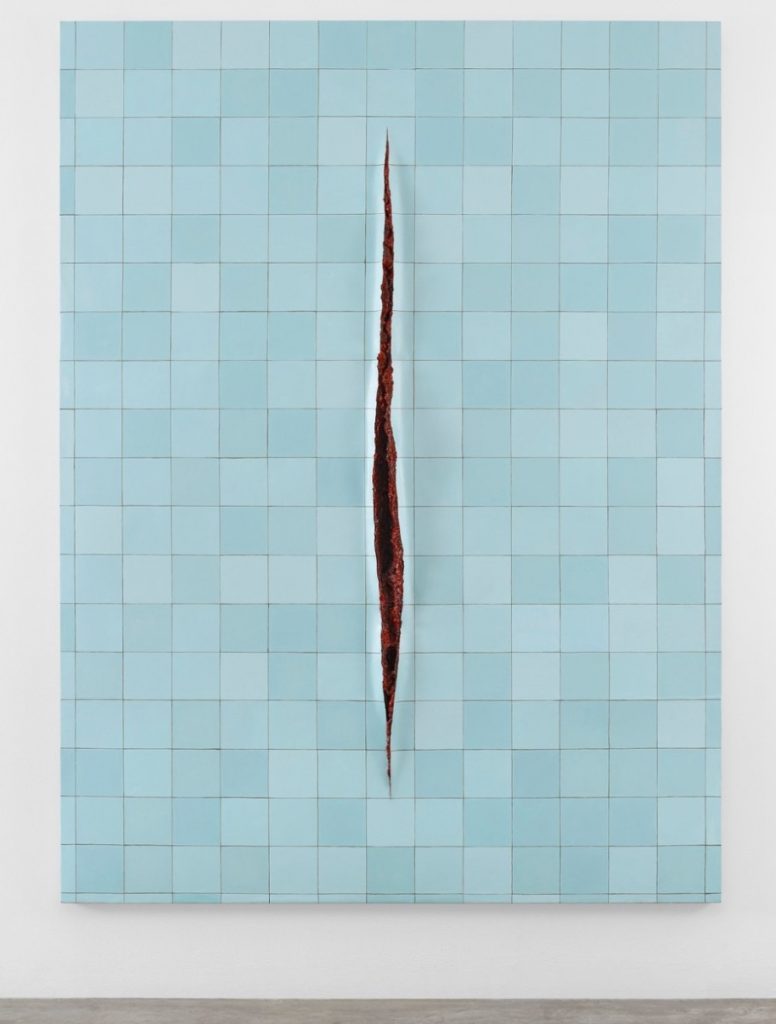

Adriana Varejao, ‘Parade con Incisao a la Fontana 3’ (2002), oil on canvas and polyurethane on aluminium and wood,

260 x 195cm

Surface Work, Victoria Miro’s survey of women abstract painters, is the latest exhibition to follow the recent trend of women-only shows. Following on from Dreamers Awake (2017) at White Cube Bermondsey, Champagne Life (2016), at Saatchi Gallery and the more substantial Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction (2017) at MoMA, Surface Work presents fifty artists, spanning 100 years of abstract painting. The proposition of the show is straightforward: an international and cross-generational ‘celebration of women artists who have shaped, challenged and expanded the language and definition of abstract painting’, and used abstraction to ‘open new paths to optical, emotional, cultural, and even political expression’. Producing an exhibition that delivers these claims without contention is, of course, less simple than the act of writing them in a gallery press release. Despite its good intentions Surface Work is flawed by its lack of complexity several times over, leaving more questions than it has answers for. Its title is taken from a Joan Mitchell quote, “Abstract is not a style. I simply want to make the surface work”. It is a wishful title for an exhibition that is curated foremost by gender and less so by formal concerns. Mitchell was notably only one of four women artists included in the Royal Academy’s disproportionally male Abstract Expressionism exhibition in 2016, but does a show like Surface Work redress such institutional imbalances, or merely continue the fashion for gender-positive shows that ultimately defeat the arguments they aim to win?

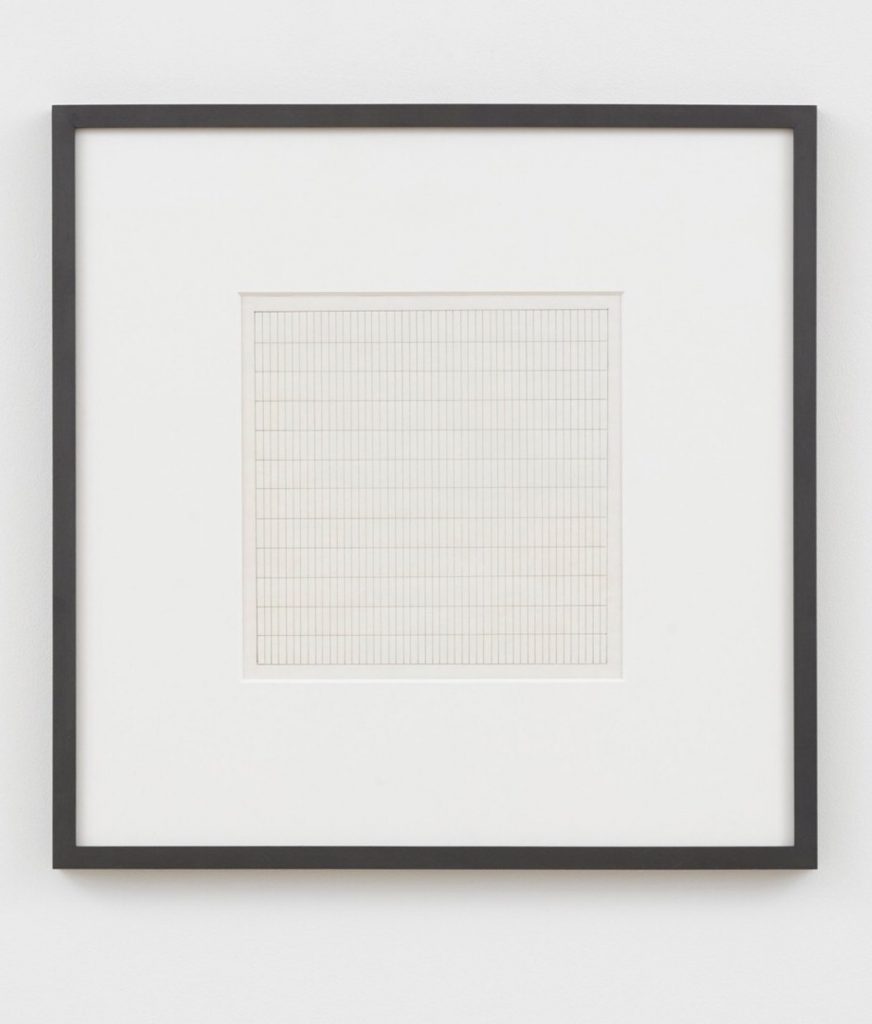

One of Surface Work’s shortcomings is that it attempts to cover too much in too little depth; adequately representing 100 years of abstract art is a punishing undertaking, and absorbing it in any meaningful way is just as difficult. There are honourable mentions for the painters who have already made it into the canon, including Lee Krasner, Helen Frankenthaler, Lygia Clark and Liubov Popova (mainly contained in the Mayfair gallery), and artists who are less familiar or lack an institutional context in the UK, such as Howardena Pindell and Tomie Ohtake. The range is commendable but within its curated breadth the artists are represented incompletely, with, in most cases, a single work demonstrating their entire oeuvre. This leads to some misrepresentation, and where women artists have made serious contributions to the advancement of abstraction, their significance remains ambiguous. Helen Frankenthaler’s Winter Figure with Black Overhead (1959) is a gestural, graphic work that does little to suggest her innovative soak-stains that were instrumental in the development of colour field painting, while Agnes Martin is represented by a diminutive pencil and ink drawing from 1995 that fails to convey the subtle nuances of her larger canvases. Many of the artists and abstract tropes in Surface Work would benefit from greater examination in order to ascertain their worth in the past century of abstraction, and this, of course, is an appraisal that should take place outside of the considerations of gender.

Helen Frankenthaler, ‘Winter Figure and Black Overhead’ (1959), oil on sized primed canvas, 213.5 x 134.6cm

Abstract painting as a paradigm has given women the opportunity to make work that is detached from personal identity, and as such can be evaluated in objective terms. The truths of abstract painting are its formal properties – the surface prioritised in Mitchell’s quote – how its component parts look, act, react, work (or not), which exist within a visual framework of judgement. As in many recent all-women exhibitions, there is a subtext of subjectivity in Surface Work that distracts from the visual truths of the paintings and introduces an extraneous narrative of the personal, and in some cases, the representational, dependent ‘image’. This is as reductive for women artists as it is for the serious assessment of abstraction itself. The exhibition guide offers some tired connections between the all-over circular configurations of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity-Nets (HNBKU) (2012) and the hallucinations from which she has suffered since childhood, and validates Agnes Martin’s fragile, fluctuating lines by reference to their ‘profound human qualities’. The intersection of female biography and the work itself is a problematic means by which to facilitate access to women’s abstraction. When can we just talk about the work, for it to be autonomously authored, objective and, yes, abstract? This is where the articulation of abstract painting in Surface Work feels particularly imprecise, located in an unspecified place inbetween perfunctory historical survey, second wave ideology and postmodern pastiche.

In the Wharf Road site, which is largely dedicated to more recent painting, the slack delineation of contemporary abstraction is more apparent. In Gallery 1 there is some decorative curation around colour and texture, in which there is a proliferation of sugary pastels and glitter. The work at best is playful and irreverent but en masse borders on insubstantial whimsy. Mary Heilmann, Lynda Benglis, Angela de la Cruz and Dala Nasser are notable for breaking the conventions of the rectangular canvas, but overall the selection of work is vapid, connections between individual pieces lacklustre, and the overall experience an unambitious compromise. The ground floor gallery is dominated by Adriana Varejão’s Parede con Incisão a la Fontana 3 (2002), a 2.5m parody of Fontana’s Concetti Spaziale, the slashed monochrome canvases he started in the 1940s to introduce a further dimension to the flat planes of painting. In Varejão’s appropriation the slash is an illusionary painted gash inscribed through her signature tiled background. It deliberately creates a visual metaphor, it is undoubtedly bodily; a wound, incision or vagina. Its inclusion in Surface Work is both puzzling and trite, it’s not smart enough to be provocative or serious enough to frame a contemporary discourse around the parameters of abstraction. Ditto Fiona Rae’s Sleeping Beauty will hum about mine ears (2017), a fluttery, avian homage to Disney’s colour palette and Rita Ackermann’s figurative and fleshy Non-dairy creamer (2013). They are unconvincing as significant works of contemporary abstraction.

Surface Work suffers in particular from boasting of museum-scale ambitions that cannot be realised in a commercial context; it lacks research, criticality and focus. Women-only reviews have too effortlessly become a new gallery norm, a now conventional way to show women that keeps them ghettoised from permanent-collection museums or commercial solo shows. In this they keep the archaic, heroic and bankable story of Modernism unscathed. There are moments in Surface Work that are creditable, exciting even, and some excellent paintings amongst the inadequate ones. However, it falls short of proving anything more than what we already know – that women can make great abstract paintings, along with, like men, some that are inconsequential. What is of concern as much as the remissive characterisation of women painters in the show is the lack of care given to any serious enquiry into abstraction itself and any meaningful suggestion of its future development.

Surface Work, Victoria Miro, London

11 April- 19 May 2018, 16 Wharf Road;

11 April- 16 June 2018, 14 George Street

Gillian Ayres, ‘Untitled’ (1957), oil and Ripolin on board, 243 x 60cm

Sandra Blow, ‘Stripes’ (1971), collage on canvas, 213 x 304cm

Lydia Clark, ‘Planos em Superficie Modulada’ (1957), gouache, graphite and cardboard, 25 x 35cm

Elizabeth Murray, ‘Maybe True’ (1988), oil on canvas, 274.3 x 229.9cm

Lynda Benglis ‘Tres (SHY FIVE)’ (2016), cast glitter on handmade paper over chicken wire, 137.2 x 27.9 x 38.1cm

Dala Nasser, ‘It’s Only a Party if You Sniff It’ (2016), marble dust, trauma blankets, liquid latex, 240 x 220cm

Liubov Popova, ‘Non objective composition’ (c.1920), gouache, oil and indian ink on cardboard, 45.6 x 28.3cm

Jackie Saccoccio, ‘Portrait (Captive)’ (2015), oil and mica on linen, 144.8 x 114.3cm

Tomie Ohtake, ‘Untitled’ (1987), acrylic on canvas, 150 x 150cm

5 thoughts on “Charley Peters: Genital Panic: Abstraction by Women in ‘Surface Work’”

Comments are closed.

It’s a truly strange situation we now find ourselves in. And ‘ghettoised’ is an astute way of putting it. As if 50% of the population is a strange and foreign other. Haven’t seen Mayfair but thought Wharf Rd hang of matching with the sofa technique really glib – actually, my 17 year old pointed it out. Ditto on some disappointing selections which I assume have a “for sale” backstory. Thanks Charley for a brave and articulate piece which underlines what I’d only say otherwise to close chums!

This is a very good essay about a difficult topic which is intelligently negotiated, and I only wish Charley had gone a little further and been more specific about the successes or shortcomings of individual works, which perhaps would have made her point even more forceful.

The misappropriation of Mitchell’s comment for the title gives away the conceit of calling all of this work “abstract” and then ascribing to it some extrinsic meaning, feminist or otherwise. Where I might differ from Charley is in her suggestion that “the truths of abstract painting are its formal properties”, which seems to me to be a reductive and somewhat conservative idea that lends itself too easily to the same old dualities. Rather, a better understanding is surely in place that the abstract content of a work can be intrinsically meaningful, without any bolt-on subject or commentary.

Thank you Charley for this brilliant piece of writing. You articulate the problems that not only we as people who make and view art face. All of us as a society encounter the guilt the art world feels hanging around its neck, this is the guilt of the people who came before and pushed female work to the furthest edges of society unless it suited them. Now that it is culturally acceptable to view work made by artists identifying as what men had previously labelled ‘the other’, it is not reasonable to critique art made by this part of humanity to the same level as that of art made by men. To allow more than just the greatest works through the doors of our galleries, our cultural litmus paper, we insult the women and other minorities that we are in fact trying to celebrate. If what the Miro was truly trying to do was participate in the ‘celebration of women artists who have shaped, challenged and expanded the language and definition of abstract painting’, they must not insult the hard work of some women with the inclusion of others just to sate the art world’s guilt.

Amazing write up, such unique artworks. This post couldn’t be written any better, “Parade con Incisao a la Fontana 3” by Adriana Varejao is amaizing!

I have come back to this after reading it for the first time in 2018 when it was published. It remains as astute and convincing as ever, and evaluates this familiar trope of female only shows brilliantly.

“Women-only reviews have too effortlessly become a new gallery norm, a now conventional way to show women that keeps them ghettoised from permanent-collection museums or commercial solo shows.”